Manuscript drawing manual

Manuscript drawing manual

Della testa... [Del disegno | Italian manuscript on drawing heads]

[Italy, 17th century]

[16] p. (the last blank) | 127 x 98 mm

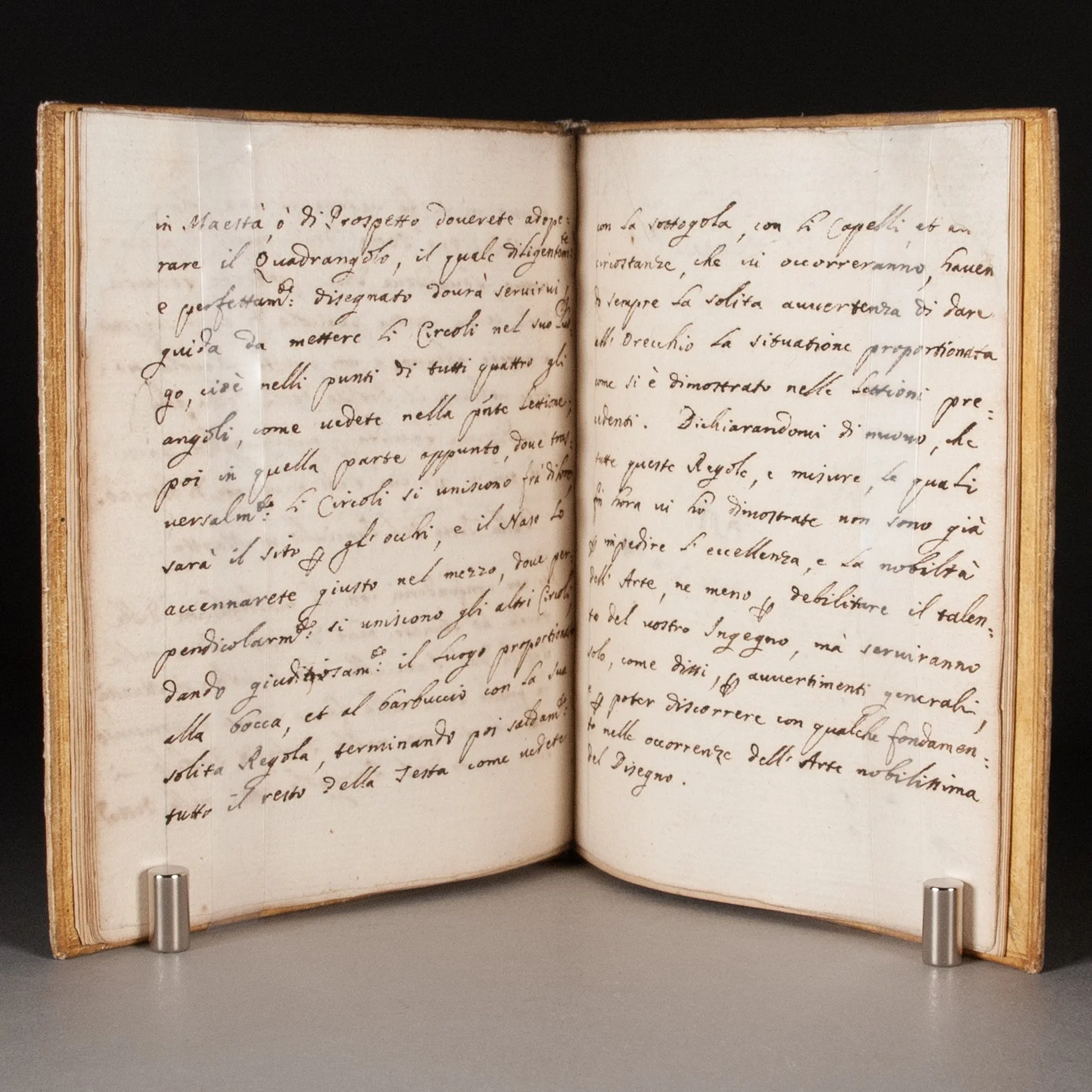

A brief handwritten guide to drawing the human head, the most important element of any figure drawing, and frequently the starting point for early modern drawing manuals. The manuscript appears to be unpublished, as we've been unable to trace the text anywhere in the vast digitized corpus. ¶ The content is divided into five brief sections, the first explaining how to draw a head in profile. Our scribe focuses on the triangle method, in which the profile is anchored by three primary points: the top of the forehead (cima della fronte), beneath the nostrils (sotto le narici), and the well of the chin or the beard (pozzetta del mento, ò barbuccio). The author then explains how to connect these points, how to form the nose, place the mouth and lips, draw the eye, etc. Our scribe closes this section with the kind of aspirational promise endemic to manuals of the time, namely that if you simply follow my instructions you'll be able to do this easily, "without much confusion and effort" (senza tante confusioni et fatiche). ¶ The second section explains how to draw the head "in majesty" (Della testa in maestà), by which the author appears to mean head-on, in such a way to convey power and authority (they elsewhere refer to this position as prospetto, e.g. on p. [9]). Here the author likewise focuses on a simple method of drawing lines between different features of the face. The third section covers drawing the head in shadow (Della testa in scurcio), which the author admits is alquanto più difficile than the first two exercises, and so they won't be sticking to such geometrical rules. But then they go on to provide a single very simple rule (una regola facile assai), namely to start with drawing a rounded oval (l'ovato circolare), and they continue with guidelines that sound to us awfully geometric. The fourth section is on drawing a child's head in profile (la testa del fanciullo in profilo), where they again start with the triangle method, adding other geometric principles and referencing the points of a compass. The fifth and final section is on drawing a child's head in maestà, wherein the author cites earlier discussion and further expounds on geometric advice. The author then closes with a general comment on the excellence and nobility of the art of drawing. ¶ The focus throughout is on lines and contours, and proportions, always guided by geometric rules for producing an accurate but relatively basic sketch. There is only brief, passing reference to elements like "hair, or other ornament, according to the need and what is most pleasing" (p. [8]: pelli, o altro ornamento, secondo che porfarà il bisogno, e che più in piacerà). Despite the brief section on drawing the head in shadow, there's nothing on rendering value, or otherwise on capturing the subtleties that give a drawing depth and feeling. Nino Nanobashvili suggests that such two-dimensional approaches to drawing, typical of early modern drawing instruction, may have stemmed from the relative abundant accessibility of prints and drawings, compared to a relative scarcity of three-dimensional models like sculptures and live models. ¶ Italy, birthplace of the renaissance, long remained Europe's go-to destination for the study of art. We wonder if these are the notes of an art student, whether from a workshop environment, or from a more academic setting. At times, the author seems to refer to accompanying drawings: come in dimostro nel p[re]sente disegno (p. [9] and [10]), or nell'altro disegno (p. [12]), perhaps quoting an instructor, or referring to drawings made or presented during class. Aspiring professionals and amateurs alike attended Italy's art academies. The head was the traditional starting point for drawing a human figure, and our manuscript would fit the prevailing pedagogical framework of "mastering parts before the whole" (Greist)—perhaps a textual accompaniment to the ABC method of drawing instruction then popular, in which students (at the Academia di San Luca, for example) would be required to draw a different part of the body each day. Or perhaps this represents an aborted attempt to creative a comprehensive drawing manual, or a distillation of instruction found in some written source(s). Whatever the case, we should note that textual accompaniment for drawing instruction was relatively unusual. "Of the twenty-three examples in my study," Greist writes, "only four Italian printed drawing books contain text." ¶ Like its spine title, the Fairfax Murray catalog calls this 17th-century, and we tend to agree based on the script. While we haven't traced our particular bird watermark, Heawood records a few similar marks used in the 17th century (and Briquet finds many in the 16th, in Italy especially. No less absorbing than the manuscript is a pair of 16th-century Italian binding covers here preserved as doublures, both heavily decorated in blind. The front doublure carries an arabesque motif and centers Alexander the Great in profile. The rear appears to have been impressed with a single panel stamp, also arabesque, both doublures betraying the Islamic influence that characterized many Italian bindings of the time. ¶ An unexpected textual witness to early modern art instruction, all the more so for an instructional landscape that heavily relied on visual models.

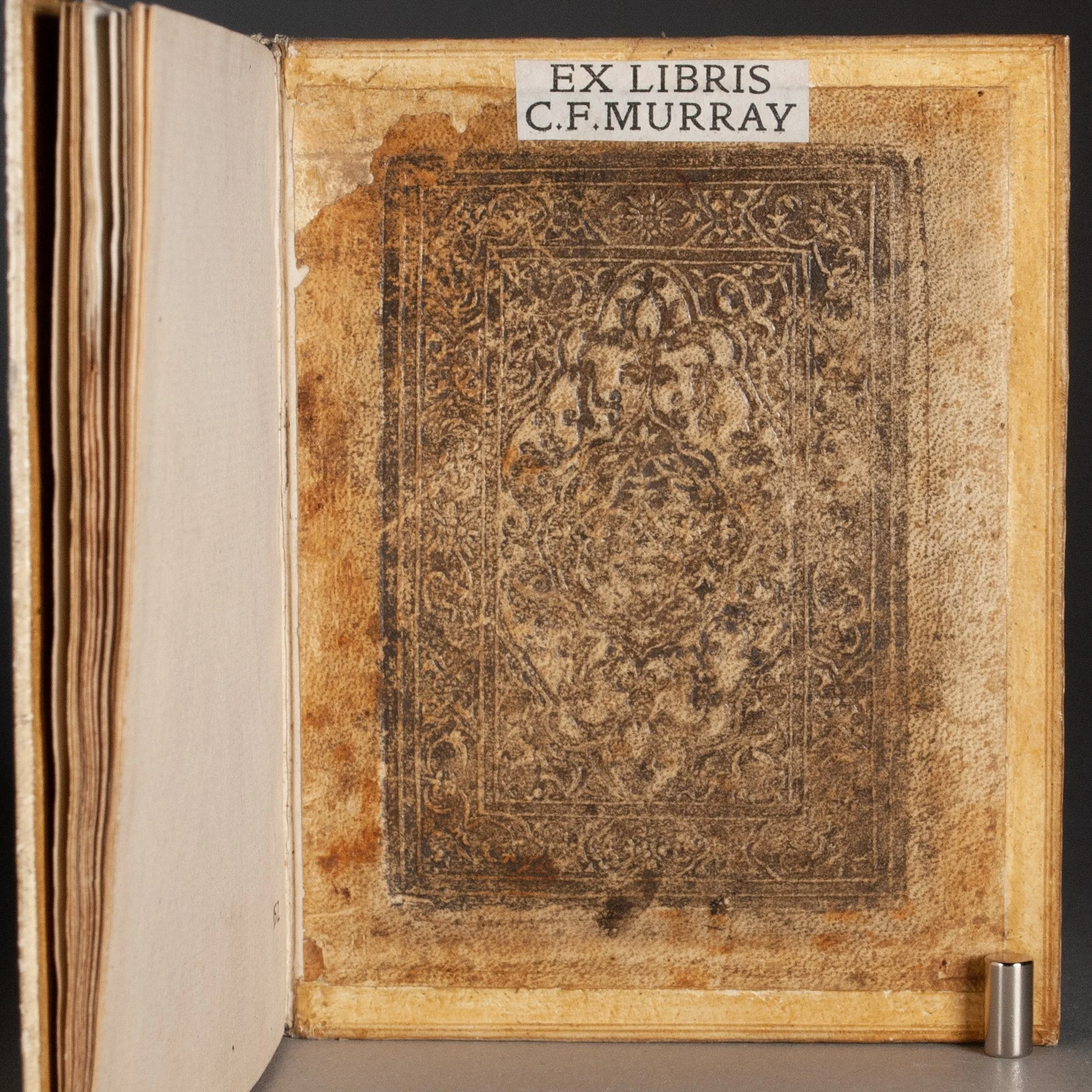

PROVENANCE: Lot 237 in the second Fairfax Murray sale (his label on the inside rear board), and perhaps then to Robert Tunstill (his bookplate on the front fly-leaf). To us from a fellow ABAA bookseller, who purchased it from a UK dealer in the 1990s.

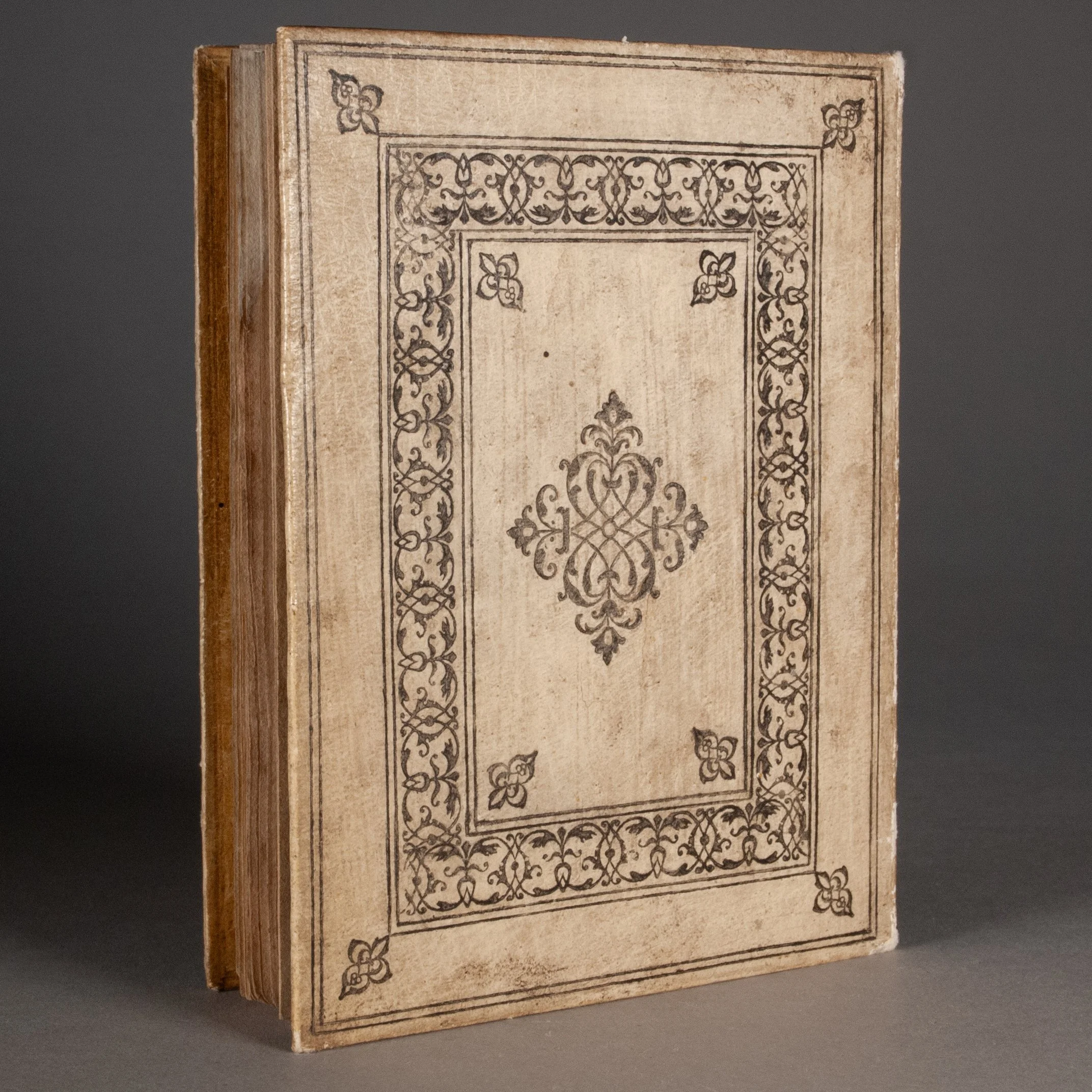

CONDITION: Written in a cursive hand in dark brown ink on laid paper, watermarked with a bird within a circle. Rebound in the late 19th or early 20th century, cream pigskin tooled in black, preserving as doublures the decorated covers of a 16th-century Italian binding (described above); title in gilt on spine (Del disegno. Ms. Saec XVII.). Following the manuscript are four additional blank leaves (save for scattered old pen trials), early but the paper different than the manuscript proper. Additionally, six more modern fly-leaves have been added at both front and back, presumably at time of rebinding. ¶ A little loss (since filled) to the upper outer corner of the manuscript leaves and the four earlier blank leaves, affecting just a word or two on each page; a few old pen trials over the text, though it remains legible. Binding extremities just lightly worn.

REFERENCES: Catalogue of the Second Portion of the Library of C. Fairfax Murray (1918), p. 42, #237 ("Manuscript on paper, italian hand, 16 pp. (repaired), white morocco extra, the cover of an old stamped vellum binding used as a doublé. 12mo. Saec. xvii") ¶ Nino Nanobashvili, "The Epistemology of the ABC Method: Learning to Draw in Early Modern Italy," Drawing Education (2019), p. 43 ("it is still questionable how useful it could be for a pupil to draw two-dimensional forms, and how could he transform these figures into lifelike images? Why did students initially have to draw such rigid images instead of studying three-dimensional examples, such as plaster casts or life models? One reason would be the availability of prints and drawings in comparison to sculptures or models. All artists owned printed examples or at least their own drawings, which were used in workshops. Drawing after a model or a nude had to be planned and were most likely expensive."), 50 ("According to Aristotle, a head is the body part created first...The start of drawing manuals by rendering members of the head and mostly the eyes seems to go back to this Aristotelian notion of procreation"); Alexandra Arvilla Greist, Learning to Draw, Drawing to Learn: Theory and Practice in Italian Printed Drawing Books, 1600-1700 (PhD Diss, UPenn, 2011) p. vii ("Italian printed drawing books (libri da disegnare) comprise an important body of evidence for our knowledge of artistic training in Italy during the early modern period...Intended for both professional and amateur audiences, these printed sources were soon copied throughout Europe where they influenced drawing education for the next 400 years"), 11 (in the early 16c, "young artists learned to draw by copying simple elements from existing models, often of a two-dimensional nature, before moving on to the more difficult task of drawing from three dimensional models"), 17-18 (a bit on Italy's art academies), 19 (cited above), 51-52 (on San Luca and the ABCs), 68 (cited above); C.M. Briquet, Les Filigranes, v. 3, #12202-#12232 (similar watermarks, mostly 16c); Edward Heawood, Watermarks Mainly of the 17th and 18th Centuries (1950), #179, #182 (similar watermarks, 17c); Anthony Hobson, Humanists and Bookbinders (1989), p. 220-221 (recording a few 16c Italian bindings with Alexander the Great plaquettes)

Item #888