Underrated genre, annotated

Underrated genre, annotated

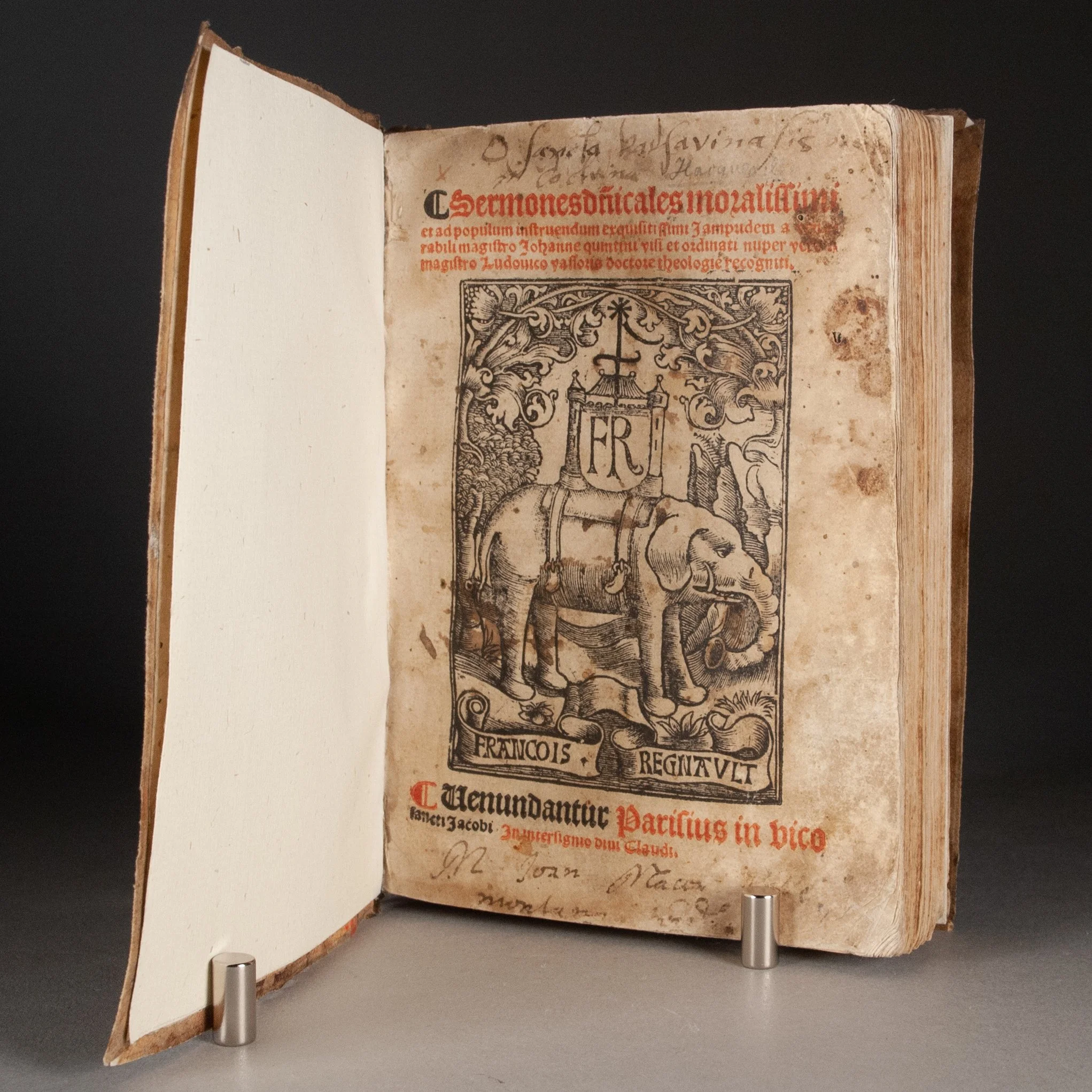

Sermones d[omi]nicales moralissimi et ad populum instruendum exquisitissimi jampridem a venerabili magistro Johanne Quintini visi et ordinati nuper vero a magistro Ludovico Vassoris doctore theologie recogniti

by Nicolas de Hacqueville (Nicolaus de Haqueville) | edited by Jean Quentin and Louis Vasseur

Paris: François Regnault, [1515-1520?]

cxliiii [i.e. 156], [4] leaves | 8vo | a-v^8 | 140 x 95 mm

A portable, undated edition of the 14th-century Franciscan preacher's Sunday sermons, first printed around 1477 and followed by at least a dozen more editions through 1540. Unpopular opinion: We find sermons a woefully underappreciated genre, if only for their capacity to illuminate the concerns of everyday life—"a mirror of taste," as Peter Bayley puts it, "a record of temperament, taste, and convention," and rich in “information about daily life, customs and ideas which is not readily available elsewhere.” USTC lists three Regnault editions, each record providing only minimal detail, though ours matches the foliation of a 1517 edition. The undated Regnault edition(s) is usually dated ca. 1515-1520, though the University of Barcelona suggests 1530 (OCLC 610690807). ¶ We find little about the author, except that his notoriety was eclipsed by a somewhat later figure of the same name. But judging by the number of editions published, his sermons were clearly popular throughout the late 15th and early 16th centuries. He preaches much on the soul, virtue, and sin (of course). And in so doing, like so many preachers, he touches on the matters of everyday life: marriage and adultery, poverty and almsgiving, homicide (don't kill people, per Sermo XXX), illness, laziness (pigritia), and more. There's something for everyone in these sixty sermons, and no doubt that contributed to the collection's enduring success. ¶ Though de Hacqueville himself had long since passed—a virtue in itself during those chaotic years of reformation—there was a broad audience for sermons of even this vintage. Certainly one might read them as a private devotional exercise, or even aloud with an audience. Others might read them as examples of oratorical prowess, not unlike Cicero. They were just as likely consumed, too, by other preachers seeking inspiration and models for their own sermons. Reputations were made by a preacher's ability to draw an audience, so it's little wonder they would mine the countless printed compilations pouring from European presses. “The age of sermons is one of the many names that could be given to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Never before had so many sermons been delivered, so frequently, and so enthusiastically" (Eire). Often they were equal parts piety and public entertainment, with good preachers filling venues to capacity (and beyond). They were quite literally the influencers of their day. (That was a little cringe, right?)

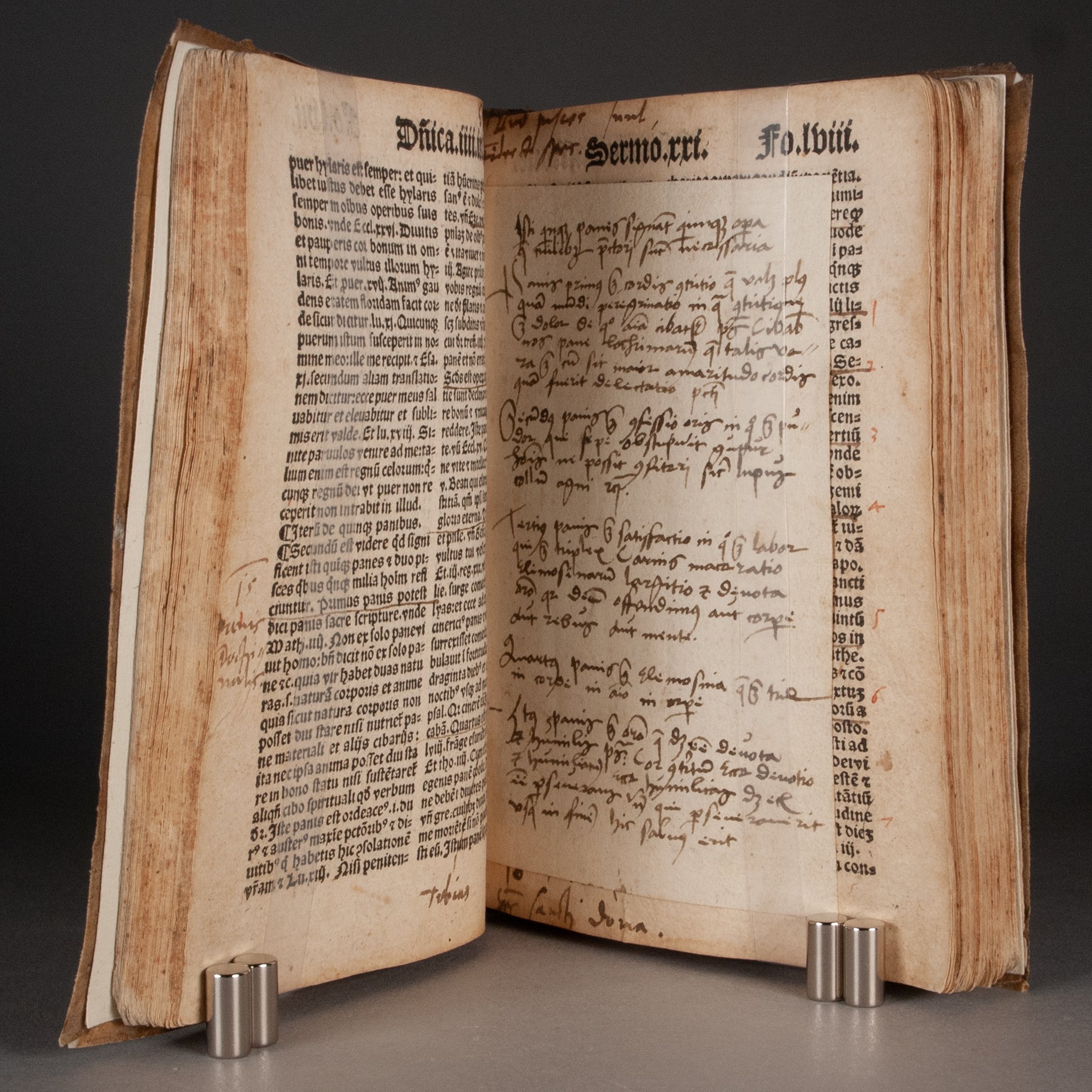

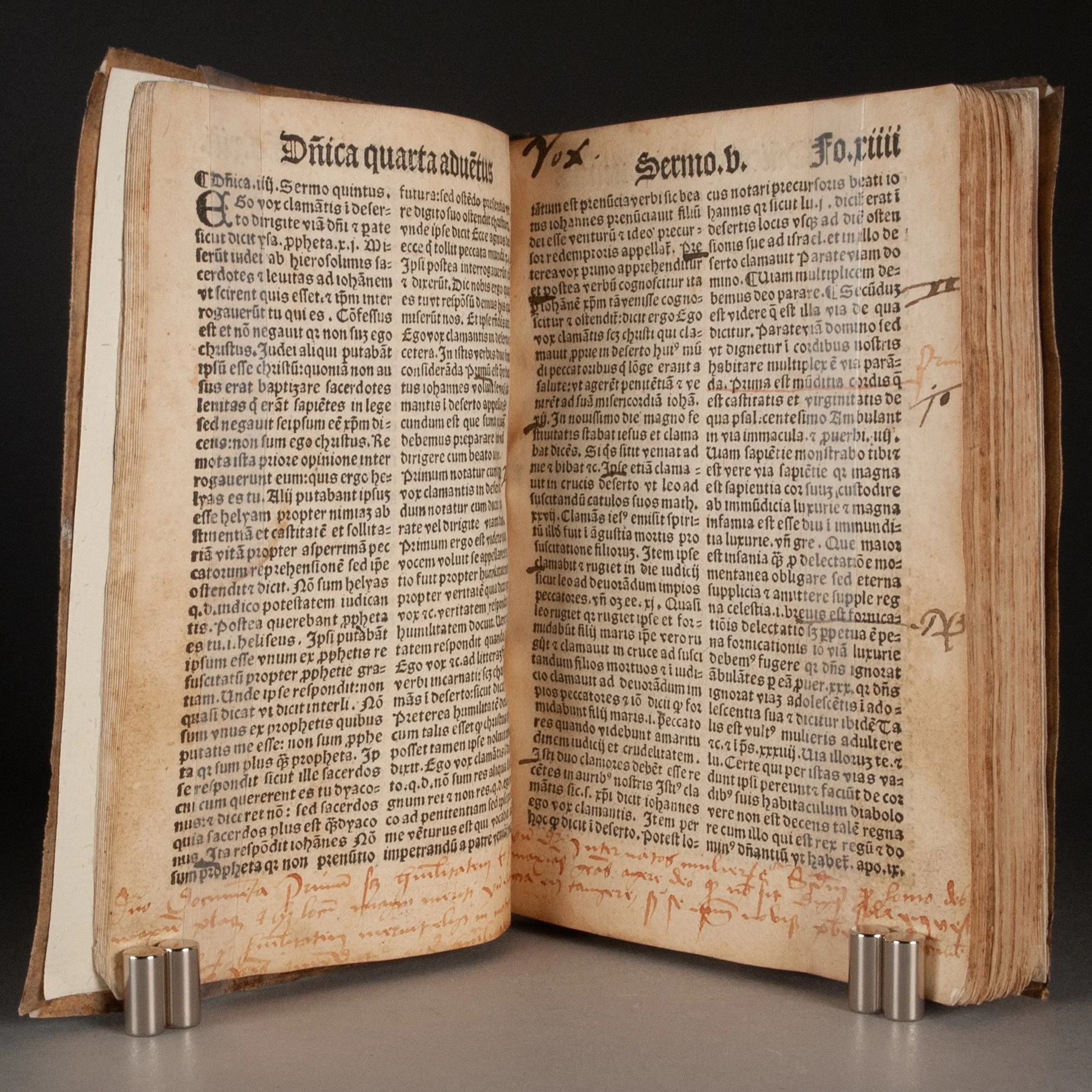

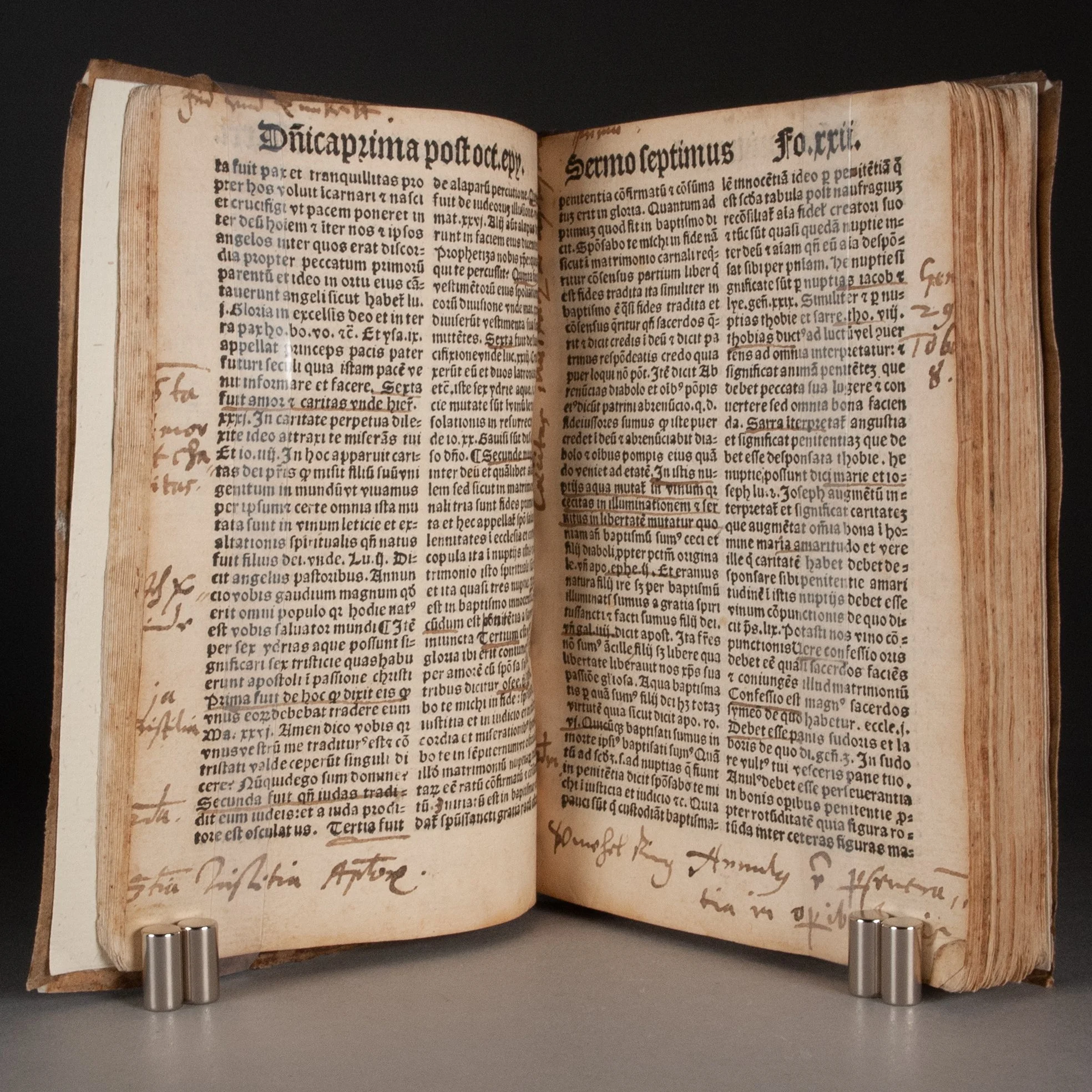

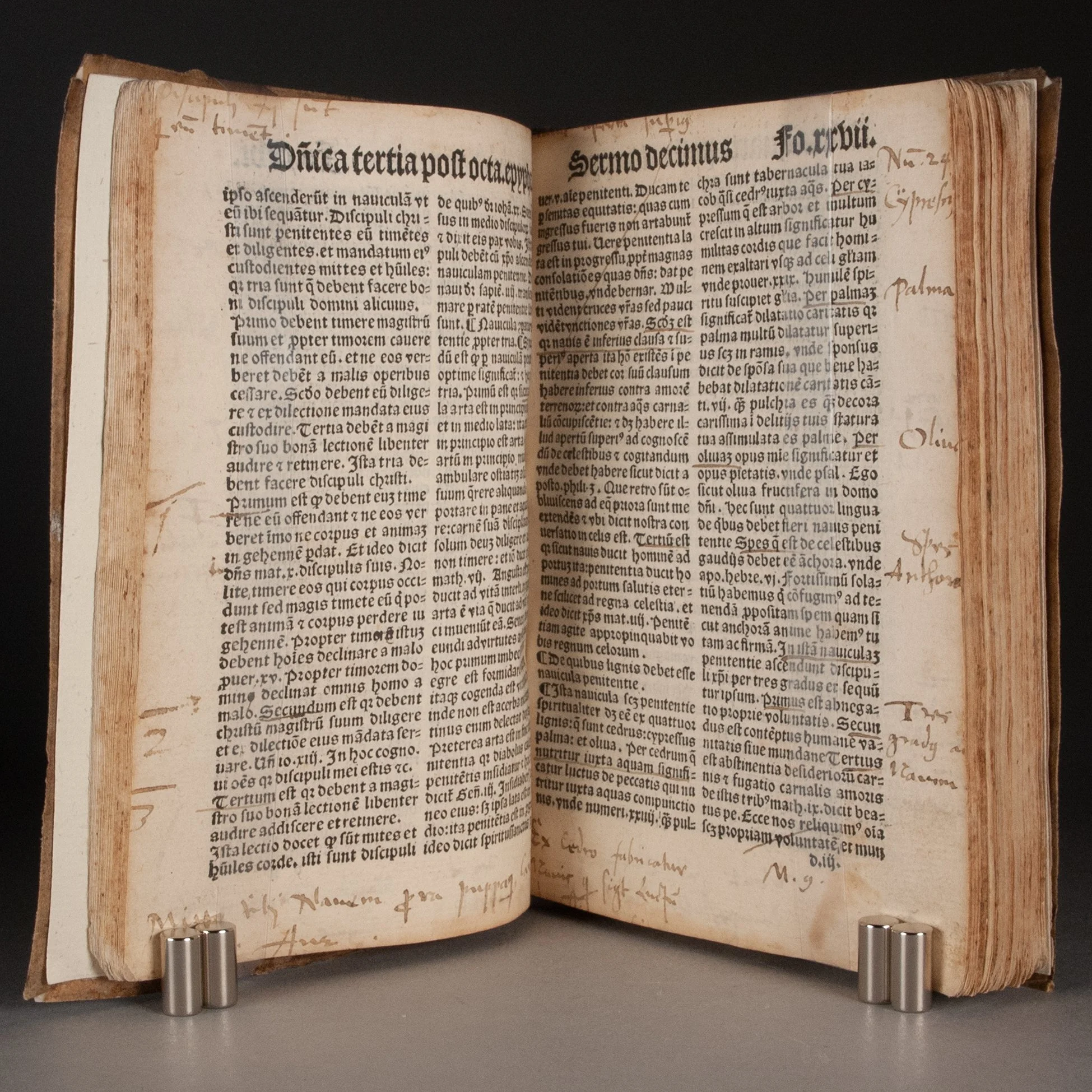

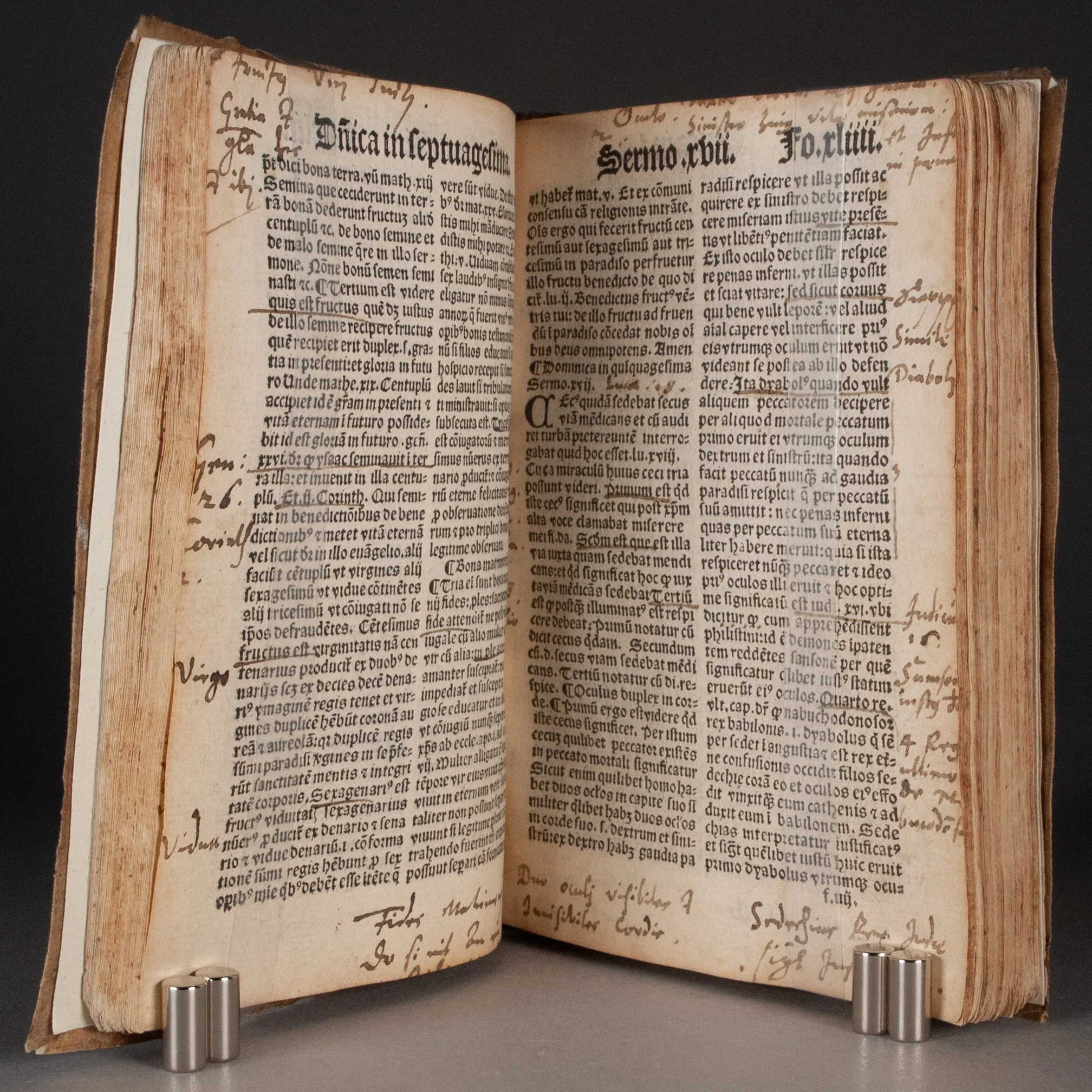

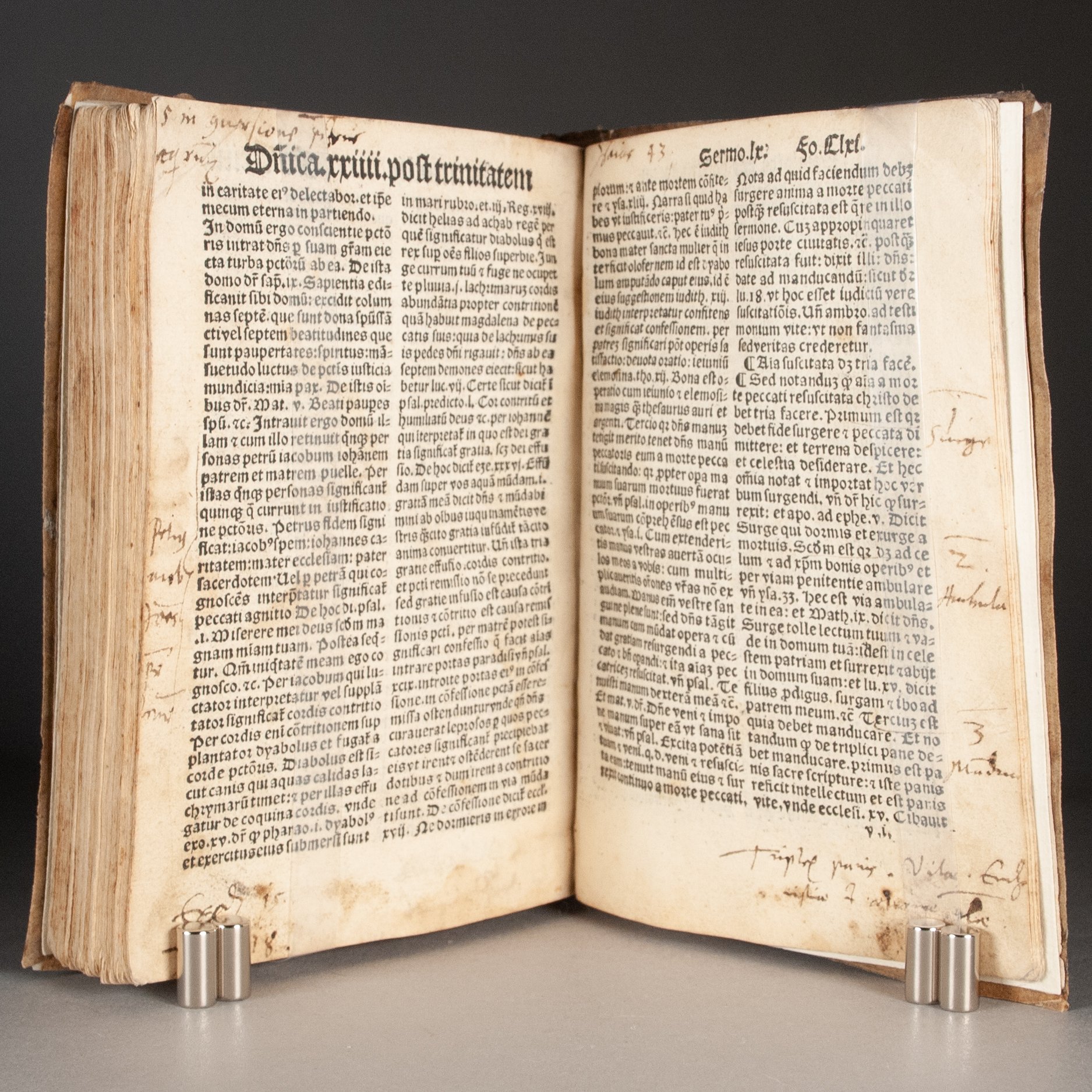

PROVENANCE: A thoroughly read copy, annotated throughout in perhaps two or three early hands, with annotations on some 200 pages. Most is of the simple wayfinding variety, presumably to facilitate recall—very occasionally a brief nota bene, but largely topical headings and brief summaries penned in the margin, often pulling language straight from the printed text. The annotations are revealing all the same, highlighting themes that captured the minds of these early readers. These sometimes appear strangely tedious. On fol. 26r, for example, an early reader has copied into the margin, "Ship made of four woods" (Navis fabricat[us] ex 4 lignis), calling attention to the specific woods used to make the boat in which Jesus crossed the Sea of Galilee in Matthew 8. Two pages later, our reader is still captivated by this theme, writing in the lower margin, "The ship is made from cedar, which signifies mourning" (Ex cedro fabricatur navis q[ui] sig[nifica]t luctu[s]). ¶ The most extensive annotation, the most obvious sign of sustained thought given to the printed text, is a separate leaf inserted to face fol. 57v. Here our reader fully explains the meaning of the five loaves with which Jesus fed a crowd of 5,000 (Isti q[ui]nq[ue] panis sign[ifica]nt...). While many annotations are brief, this one stands out as the clearest sign of sustained thought given to the printed text. And while our annotations largely remain anchored to the present text, we suspect one looks outward, comparing the sermon to something altogether different: Are we misreading, or is that "Aesop is full of foxes" on fol. 35v, beside a passage discussing the wily animal (Aesopus su[n]t pl[e]nam vvoll.)? ¶ Invocations to St. Catherine on title page and final blank page. Partially obliterated early ownership inscription at foot of title, for one Joannis. Ink stamp on title verso of the Hofbibliothek Donaueschingen, the library of the House of Fürstenberg, which began selling off its post-1500 printed books in 1999. The Württembergische Landesbibliothek had already bought what remained of its manuscripts in 1993, and Sotheby's auctioned its remaining incunabula in 1994.

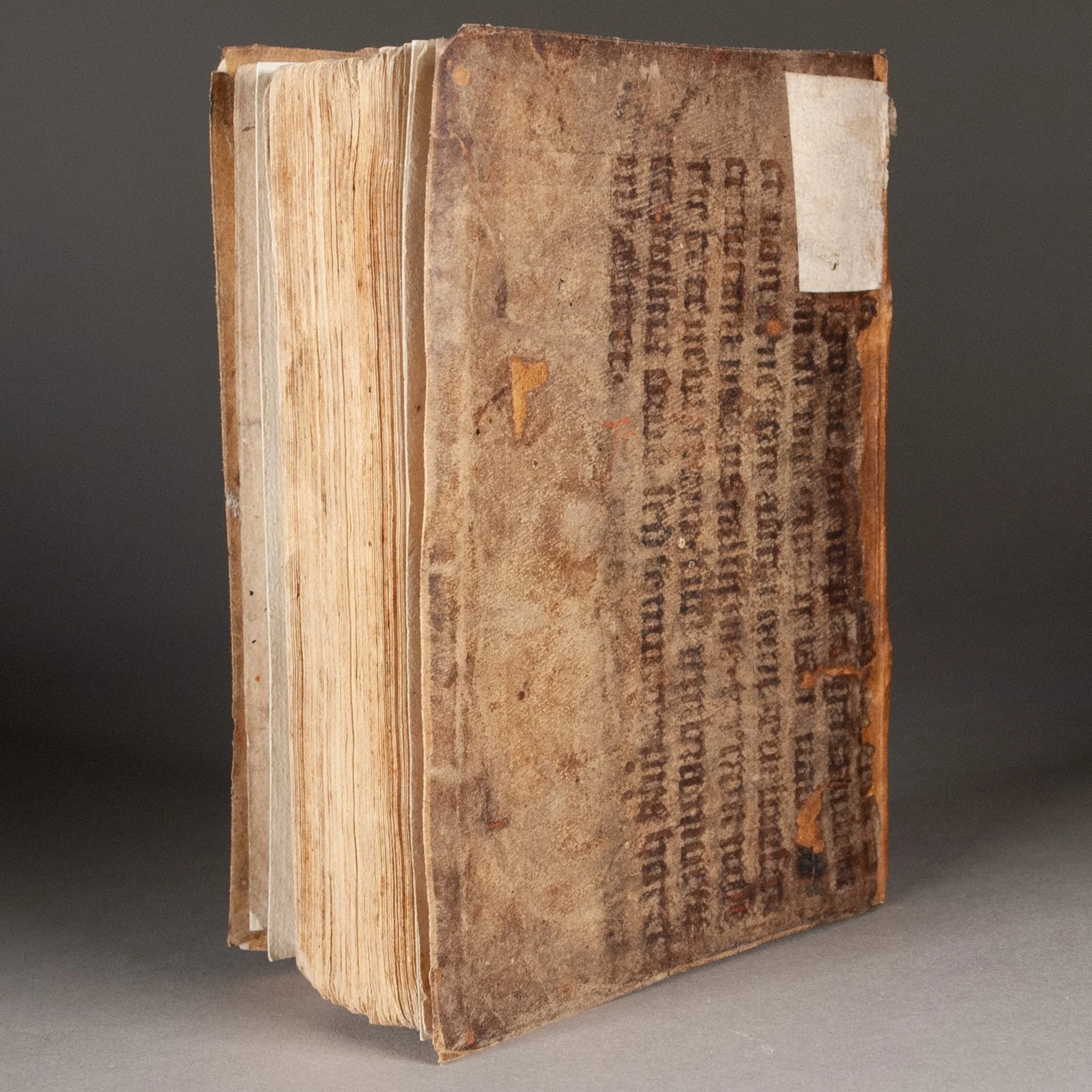

CONDITION: Contemporary binding of medieval manuscript waste, probably religious in content (a rubric on the front cover appears to cite the Gospel of John). Old paper title label on front cover, partially obscured by more recent paper label. Large woodcut printer's device on title. ¶ The text of the headlines in our final gathering is smaller than elsewhere in all preceding, and there's some missing text in the transition from sermons 59 to 60. Yet the early marginalia spanning the t8/v1 spread is in the same hand. We suspect the printer may have had extra sheets from an earlier edition and supplied one here. ¶ Title and final page heavily soiled, with scattered mild soiling throughout; some marginalia trimmed; light dampstain to the first few gatherings; some marginal loss to the title (discreetly repaired), not affecting text. Recased with parchment, the medieval waste covers mounted atop this, with new endpapers added; additional repair at the head of the newer parchment spine, using manuscript waste; parchment wormed and heavily soiled.

REFERENCES: USTC 144814 (edition uncertain) ¶ Carlos Eire, Reformations (2016), p. 596 (cited above; " Nearly everywhere, good preachers could draw overflow crowds. In Spain, it was not uncommon for people to line up outside of church overnight, waiting for the doors to open, just to hear a popular preacher"); Peter Bayley, French Pulpit Oratory (1980), p. 3 (“it is an art of persuasion, linked to the European rhetorical tradition; unlike forensic oratory, it takes for its themes great commonplaces which require skillful presentation if they are not to collapse into banality; finally, it is a mirror of taste"), 4 (cited above), 6 (cited above); Emily Michelson, The Pulpit and the Press in Reformation Italy (2013), p. 1 (“the sermon was the sole moment of comprehension in a religious culture that existed entirely in Latin, and it would remain so until the middle of the twentieth century"), 5 (sermons “have a great deal still to tell us about the perspective and concerns of the early modern world"), 17 (“Sermons were also a form of public entertainment, and a sermon audience was a desirable place to be seen. Popular preachers traditionally filled churches to capacity or had to move outside to the adjoining piazza in order to accommodate the crowds…Local governments invited illustrious preachers to their cities and competed with each other to get the best ones…A preacher with a good reputation could spend nearly his entire career traveling from city to city, taking up temporary residence and delivering a sermon cycle to the local population.”), 31 (“Through a printed sermon in any form, a solitary reader could find a sense of community and feel himself part of the original preached event"), 32 (“Such collections could equally appeal to literate and educated laypeople: not only the cardinal but his wealthy brother or the tutor to his sons, the religiously minded diplomat, or the newly rich silk merchant wanting to prove his piety and property…Furthermore, published sermons, like many books, were as likely to be read aloud as silently, and often in groups, thus recreating some of the sermons’ original audible drama.”); Catherine R. Evans, "Locating Devotion: Sermon Title Pages and the Early Modern Book Market, 1620-1642," The Library 7th Ser 24.1 (Mar 2023), p. 4 (“The part that sermons played in early modern literary culture has been, if not overlooked, then perhaps undervalued"); Miriam Usher Chrisman, Lay Culture, Learned Culture: Books and Social Change in Strasbourg, 1480-1599 (1982), p. 85 (“A major purpose of these collections was to provide parish priests with ready-to-preach sermons, as was explicitly stated by Johannes de Verdena, a German Franciscan," speaking of 15c collections, but the principle endured)

Item #736