Regimen sanitatis manuscript doubles as memo book

Regimen sanitatis manuscript doubles as memo book

Le regime de lescôle de Salerne [Regimen sanitatis Salernitanum]

with commentary by Arnaldus de Villanova

[France? not before 1633]

[1], 16-100, [4] p. (all after p. 60 blank) | 8vo | 161 x 105 mm

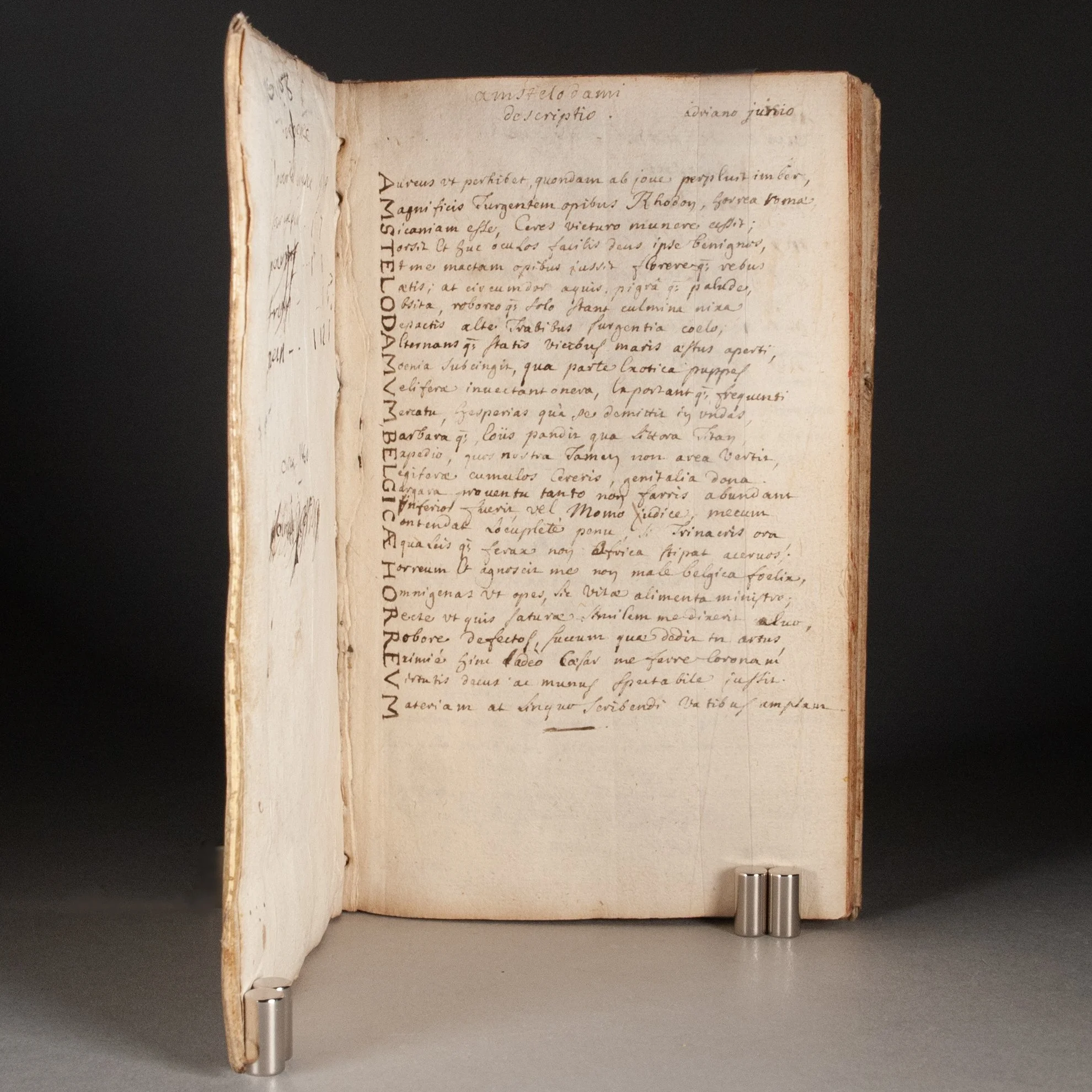

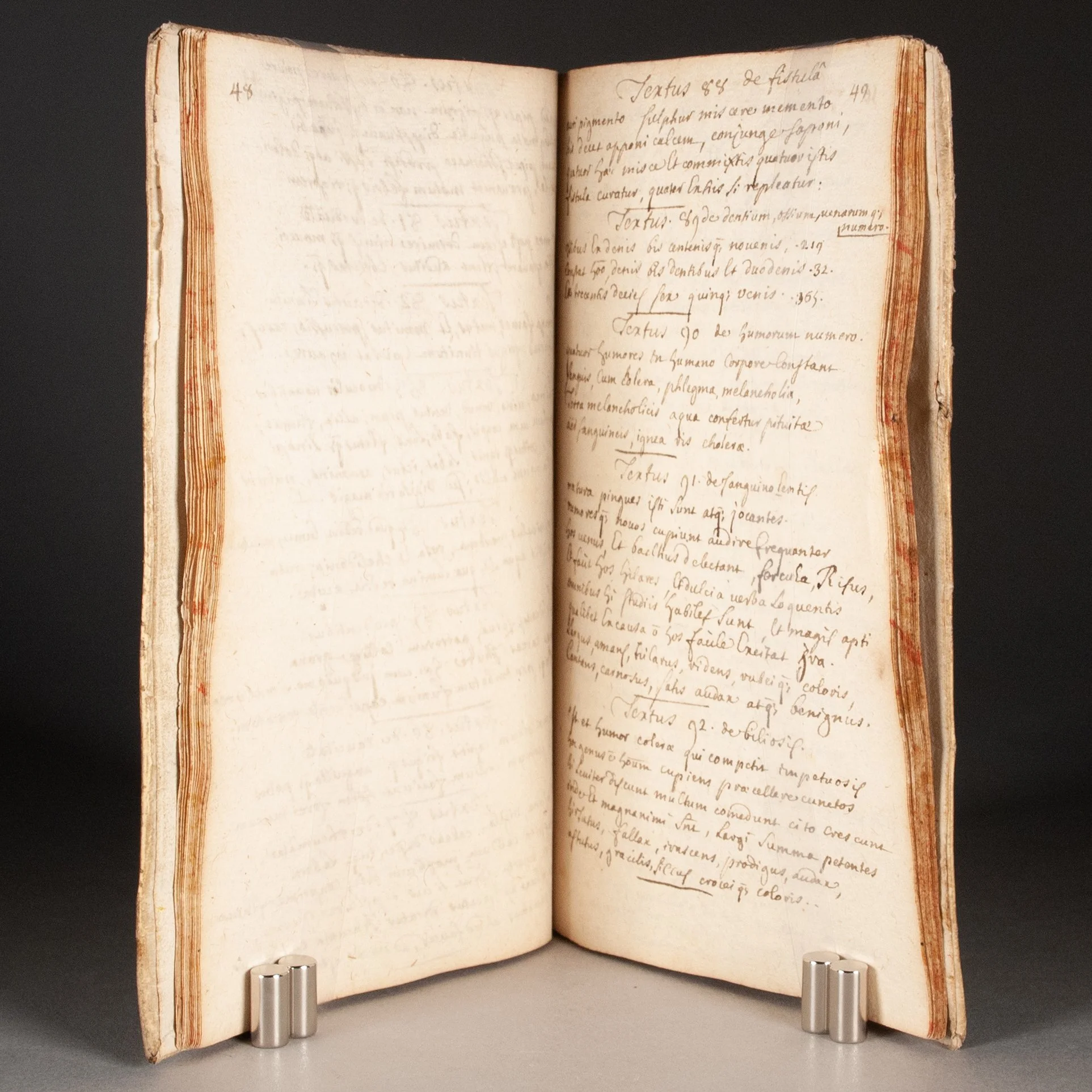

An unusual, late manuscript copy of the highly influential 12th-century medical treatise from the community at Salerno, generally considered the West's first medical school not affiliated with a religious house. At a time when the poem was invariably published with voluminous commentary and other add-ons, our copy rather unusually presents strictly the original Latin text, for an admittedly more portable format. By the end of the 16th century, the text came in dozens of versions: various lengths, with myriad additions and subtractions, ranging from a few hundred to a few thousand lines; lines arranged in different orders, sometimes whole passages moved, sometimes a pair of lines simply swapped; and with countless variations in word choice. Ours is the recension prepared by Michel Le Long for his own French translation (Le régime de santé de l'eschole de Salerne), first published in 1633, with subsequent editions in 1637, 1643, 1649, and 1660 (the last at Rouen, all others at Paris). We take special note of Textus 36 here arranged Pisum laudare... / Pellibus ablatis... / Ab inflativa... (p. 31). The second and third lines are typically swapped in later arrangements. We last find our arrangement, common through the early 17th century, in Le Long's 1660 edition, then not again until 1790. ¶ Le Long's Latin version runs to 388 lines of verse—each short textus introduced with an additional single-line subject—and hews very closely to the first expansion attributed to Arnold of Villanova in the mid-1200s. For example, we have his addition on p. 27 (Ilia bona sunt porcorum, mala sunt reliquorum), but not on p. 29 (Vina bibant...potus aquae after inde cibus). The work focuses heavily on diet, and offers a good deal on therapeutics, but also touches briefly on countless other topics relevant to one's health: sleep, air, hand washing, complexion, bloodletting, and more. There's a bit of anatomy, and treatments for everyday ailments like hangovers and seasickness. Hangovers must have been common since wine was the go-to prescription. And the treatment for said hangover? "Drink again in the morning; it will be your best medicine." The work became a standard text in medical curricula, was widely translated, and appeared in scores of printed editions throughout the early modern period (including more than three dozen in the fifteenth century alone). ¶ The profusion of printed editions should suggest ready availability, but this manuscript's very existence suggests that, for whatever reason, the Regimen's vast printed presence could not satisfy every particular demand. While most of the hundred or so manuscript copies identified by Lafaille and Hiemstra date to the 14th and 15th centuries, they do report 16th- and 17th-century outliers. "Manuscript diffusion remained an important method of book diffusion until the end of the 18th century. Various reasons explain this choice for certain works or for certain genres: economic constraints, desire to control the circulation of texts, imperatives of prudence and discretion" (Sordet). Perhaps our owner wanted a copy shorn of a cumbersome accrued commentary, or found the critical editions then popular simply not worth the cost. Perhaps our owner lacked ready access to a copy for sale, rather only an exemplar from which to copy their own. Or perhaps, as was the case for many devotional manuscripts, copying the text was meant to improve focus and retention. ¶ The Regimen is sometimes attributed to Trota of Salerno, a woman who studied there in the 12th century, but her output should be limited to the three texts on women's health collectively called the Trotula. Our manuscript also includes at front an acrostic poem on Amsterdam taken from Hadrianus Juniu's Batavia(editions in 1588, 1589, 1652, and perhaps 1692). There's a temptation to suggest Amsterdam as place of production, but given the French exemplar from which it was copied, and the French annotations, we give the edge to France (but recognize the possibility of a French speaker abroad). ¶ A surprising manuscript witness to one of the West's essential medical texts, copied during the waning years of its influence. We find no auction records for any manuscript copies.

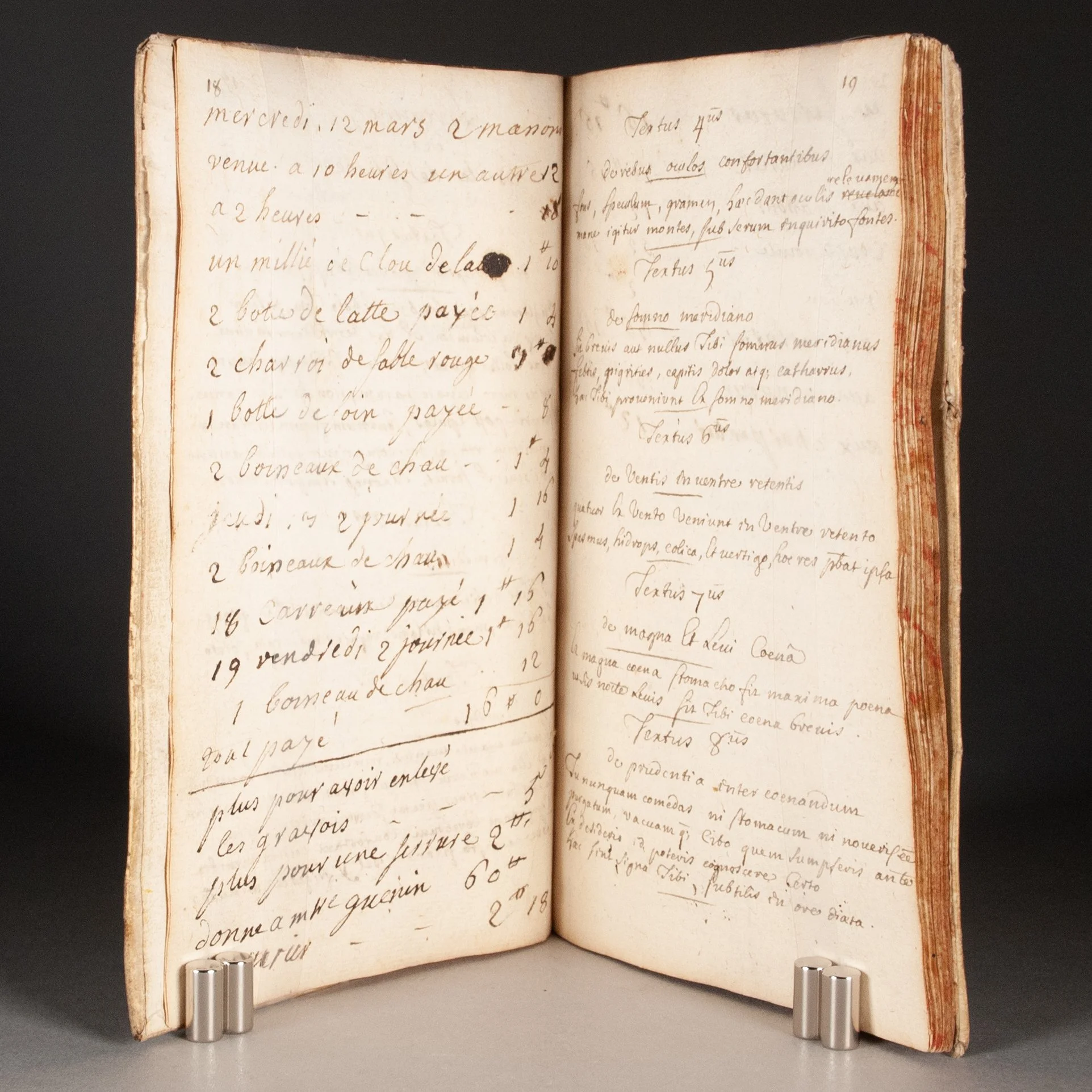

PROVENANCE: With a handful of scattered quotidian annotations in French from the later 18th century. Written on the front paste-down are several expenses, including cheese (fromage), and perhaps a grape vine (la vigne) and a pine tree (un pin). On p. 16 are a handful of names and titles, starting with the priest for the owner's parish (curé de notre paroisse). On p. 18 our owner has listed a full page of expenses, including a thousand nails (un millié de clou) and quantities of lime (chau); p. 20 lists eight further expenses (locksmith, joiner, carpenter). Page 60 lists three parcels of land, one of them in the parish of Mehun (presumably Mehun-sur-Yèvre), and the rear paste-down lists one final expense dated October 1776. Obviously none of these notes has any bearing on the Regimen text, but underscore the role played by blank paper anywhere as a platform for memoranda.

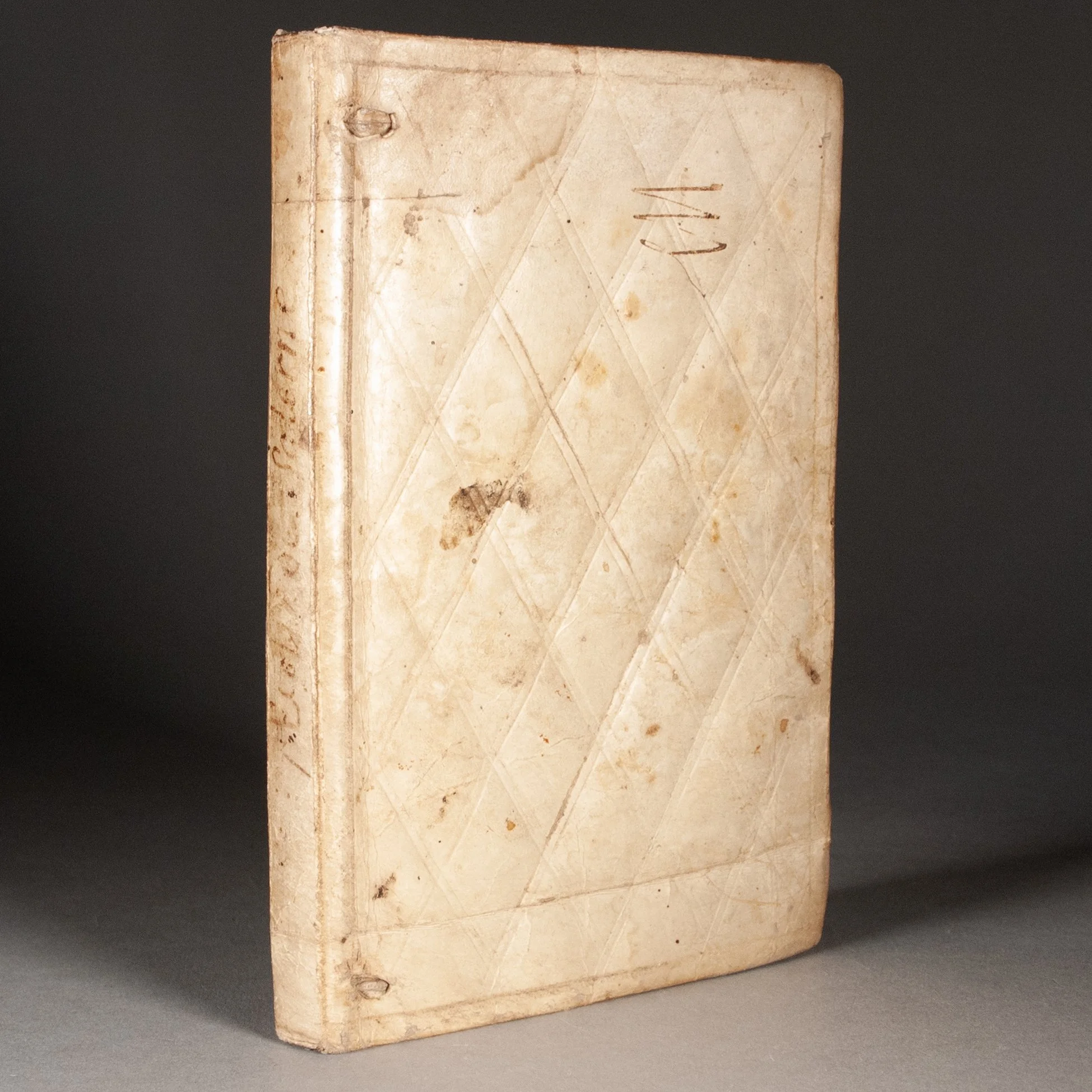

CONDITION: Brown ink in an italic hand on laid paper, without any visible watermark. Bound in contemporary parchment blind-tooled with a diaper pattern; edges sprinkled red; title inked on spine. The Regimen written on the rectos only, the versos blank save for the aforementioned French annotations. ¶ Some half a dozen leaves removed at front, and perhaps two dozen at back. We suspect the owner plundered the back of the volume for blank paper (and perhaps even the front). In any case, the Regimen is complete. ¶ Edges of the leaves a bit dusty, and a small piece torn from blank p. 69/70. Spine a trifle cocked and parchment soiled, with a 3 cm slice at the bottom of the rear board. A solid book.

REFERENCES: Robert Lafaille and Hennie Hiemstra, "The Regimen of Salerno, a Contemporary Analysis of a Medieval Healthy Life Style Program," Health Promotion International 5.1 (1990), p. 57 ("Until now this research and analysis has revealed circa 100 manuscripts, most of them from the 14th or 15th century, others from the 16th or 17th century. These manuscripts differ greatly."); Anne van Arsdall, "The Medicines of Medieval and Renaissance Europe as a Source of Medicines for Today," Prospecting for Drugs in Ancient and Medieval European Texts (1996), p. 34-35 ("The University at Salerno in Italy had the first non-monastic school devoted to medicine in the West" and calls this "an extremely famous text from the Middle Ages through the Renaissance; three hundred manuscript and printed versions of the work have been identified"); Yann Sordet, Histoire du livre et de l'édition (2021), p. 445 (cited above); John Varriano, Wine: A Cultural History (2010), p. 89 (on the hangover cure); Charles Singer and Dorothea Singer, "Historical Revisions: XXXV—The School of Salerno," History New Series 10.39 (Oct 1925), p. 242 ("The earliest European institution to develop an organisation that bore a semblance to a university is said to have been the medical school at Salerno, an ancient sea-port in Southern Italy not far from Naples," and calling it "the first medical school in Europe, which flourished in the eleventh and twelfth centuries"; "Some of the better known and widely circulated [medical texts] include Arnold of Villanova's commentary on the Regimen sanitatis in the mid-1200s at Montpellier"), 244 (disputing attribution to Trotula, suggesting instead trotula would have been the common title given to work produced by one Trottus, a physician at Salerno)

Item #885