Showboating poetry in unrecorded incunable

Showboating poetry in unrecorded incunable

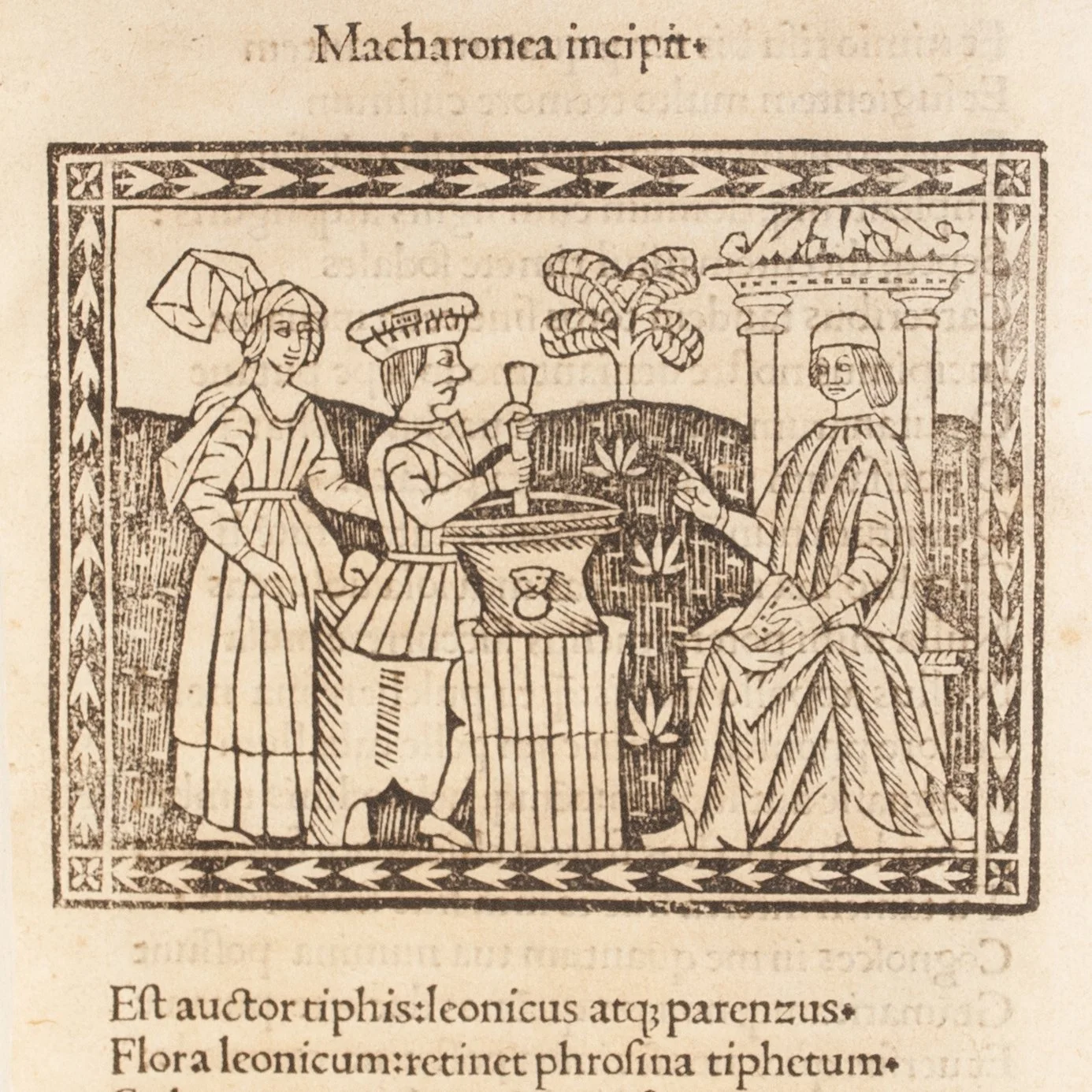

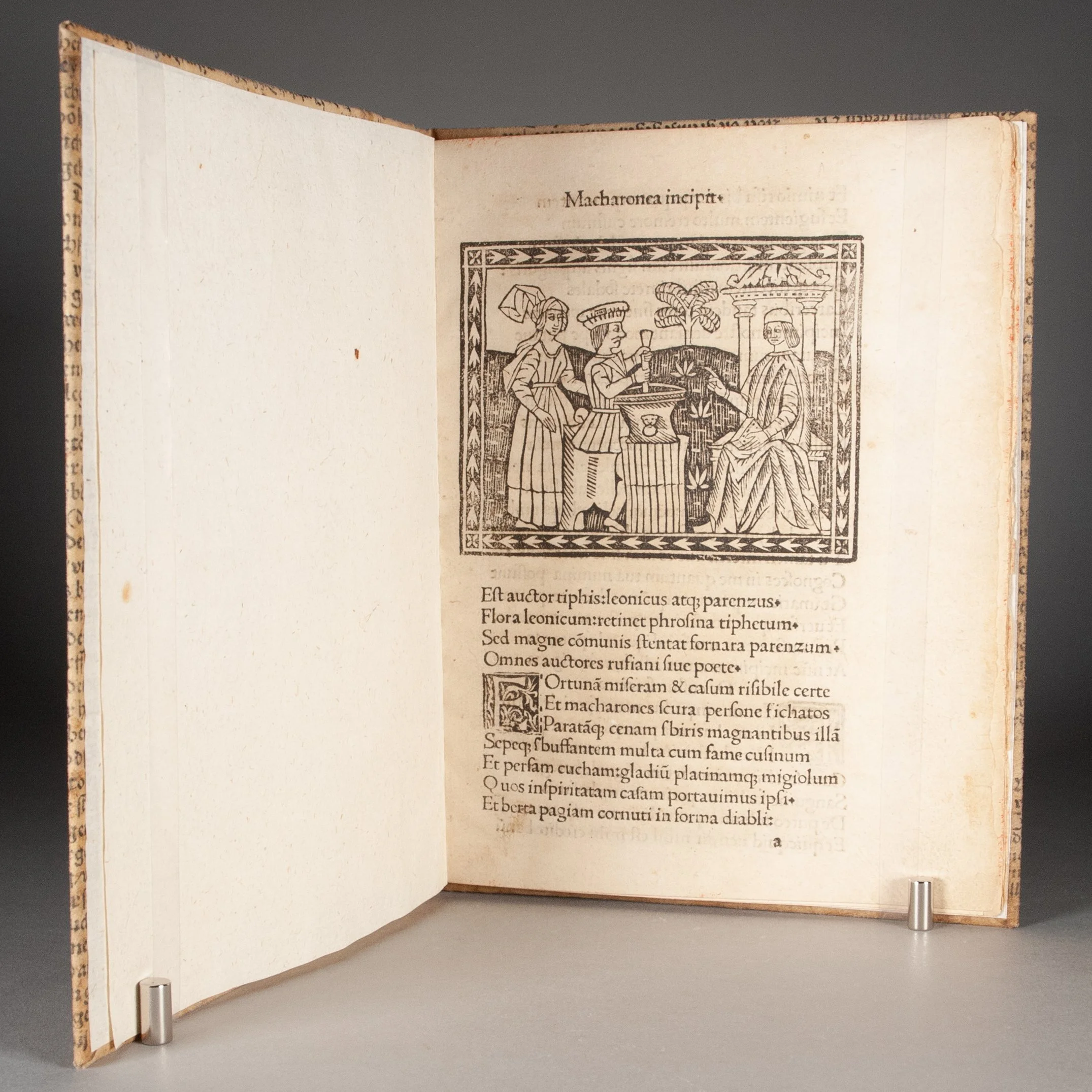

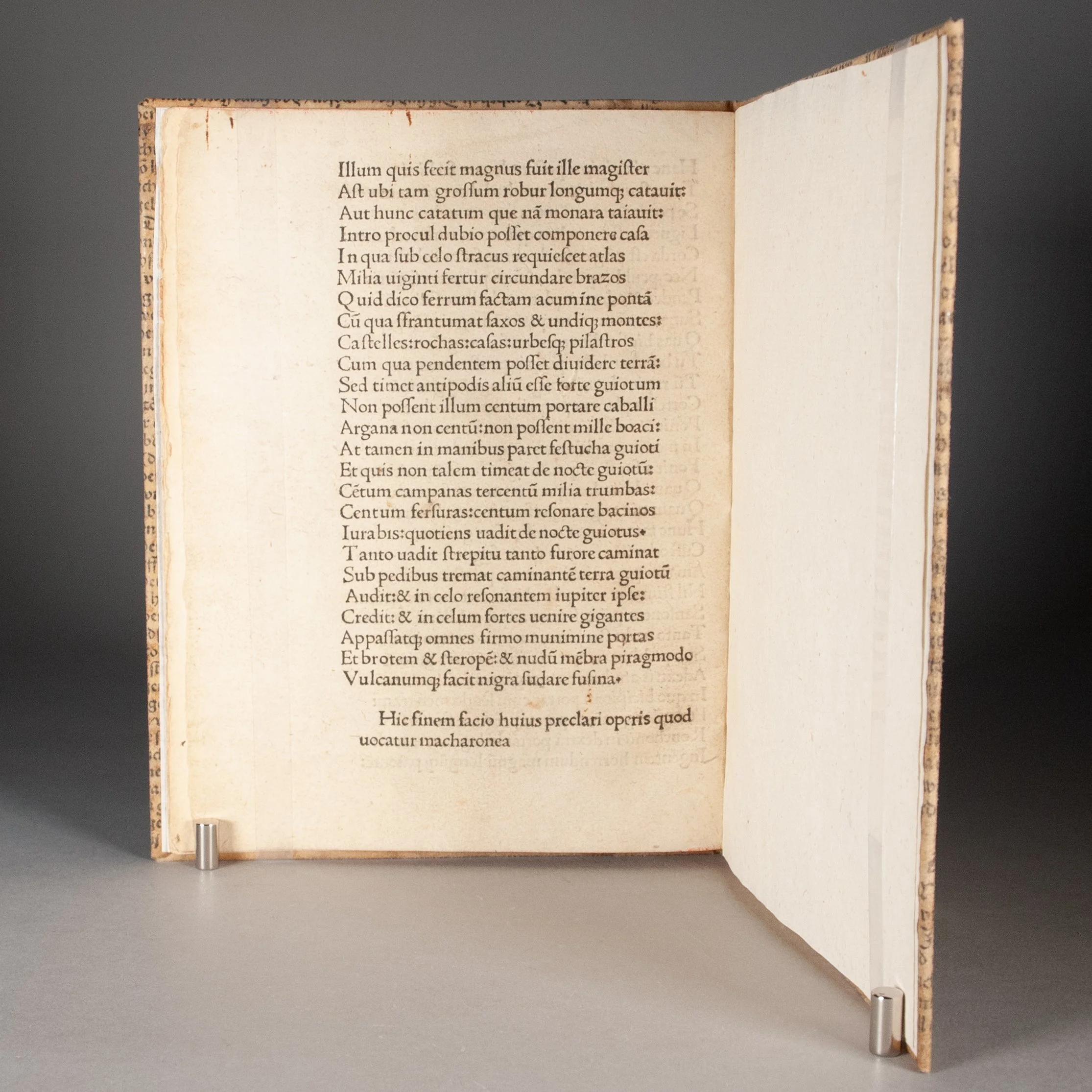

Macharonea incipit [La macaronea]

by Tifi Odasi (Michael Odaxius)

[Rome: Eucharius Silber, not after 1499]

[12] of [12] leaves | 4to | a-c^4 | 197 x 153 mm

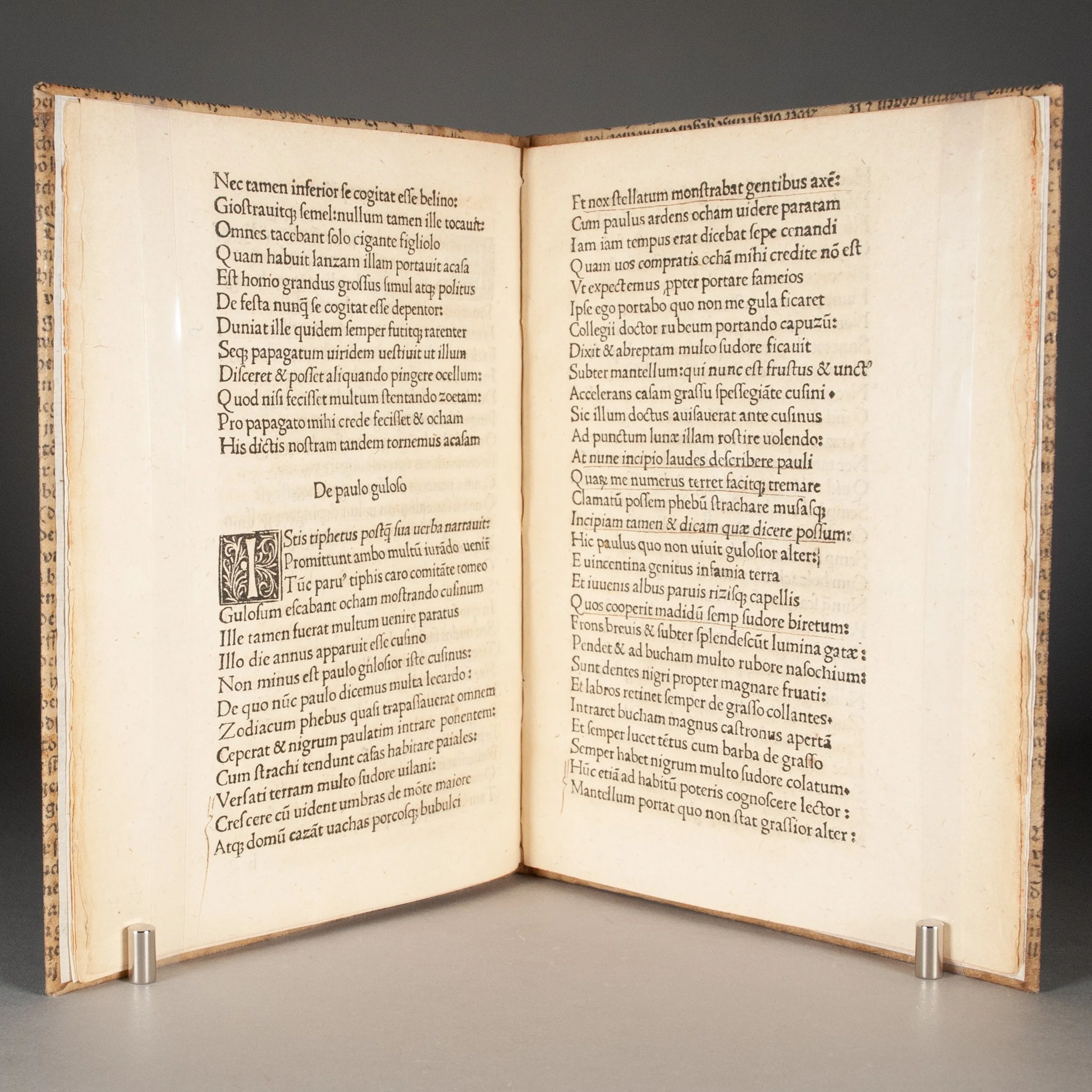

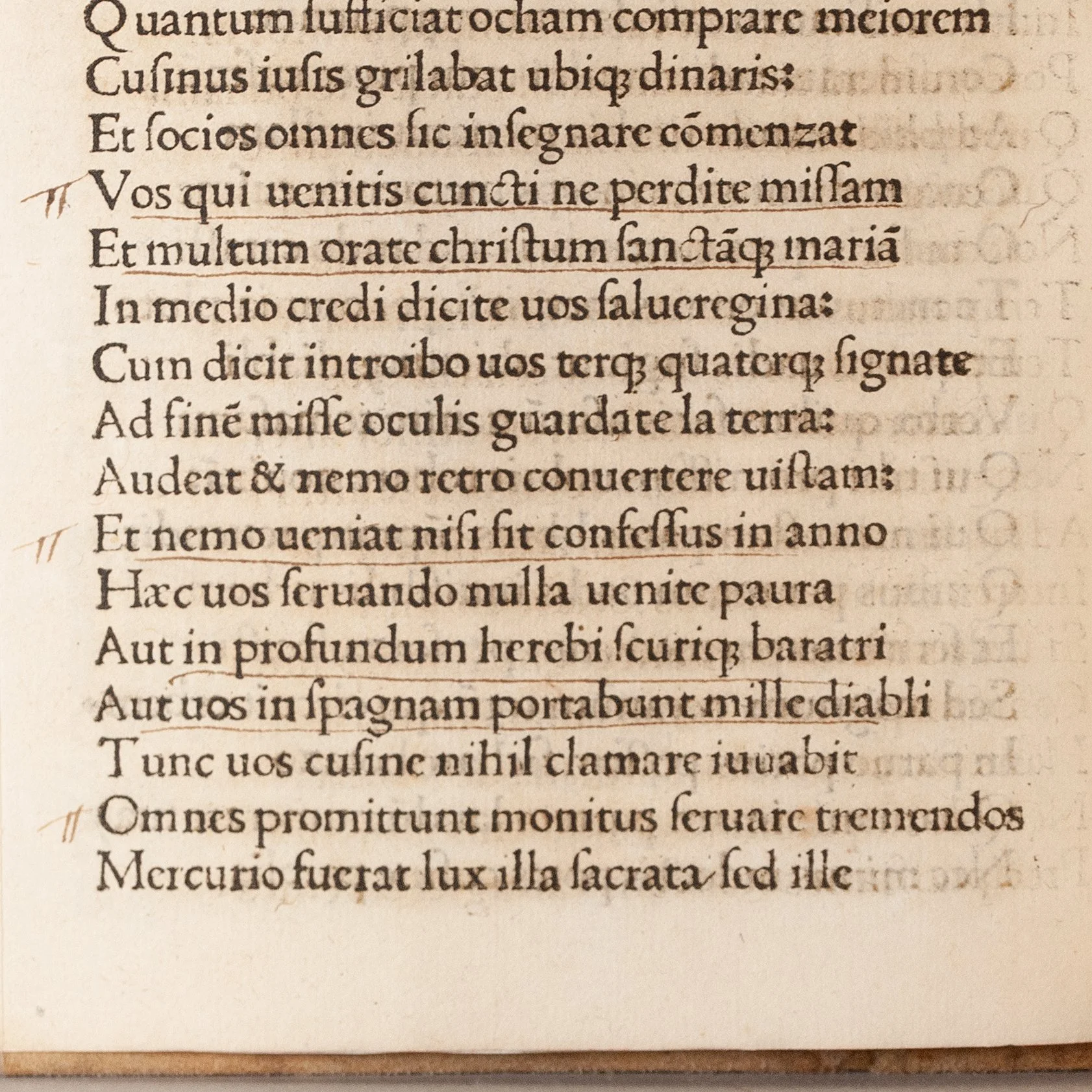

An unrecorded incunable edition of the Paduan humanist's burlesque poem—the very namesake for macaronic poetry, a playful blend of different languages calling to mind the more famous (and slightly later) Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. The work was in print possibly as early as 1485, though every single 15th-century edition is undated. Our edition lacks any identifying information, but the type and decorative initials mark it as a previously unknown imprint from the prolific Roman press of Eucharius Silber, printed perhaps ca. 1497, and almost certainly not after 1499. All recorded editions are Italian imprints, most of them 15th-century. ISTC reports no more than three copies for any of these six editions—half of them represented by a single copy only—which should place our stealth survivor in understandable context. We also find a copy at Parma's Biblioteca Palatina, the lone survivor of yet another unrecorded Silber edition, underscoring the work's remarkably low survival rate. See below for a fuller discussion of our dating. ¶ Macaronic poetry is typically traced to the late-15th-century university crowd in Padua, though we should note that the literary blend of two languages is hardly a renaissance invention. Consider "The Phoenix," for example, a tenth-century Old English poem that switches to a mixture of Latin and Old English in its final lines. But the macaronic poetry that Odasi wrote—and whom many credit with inventing—is something more sophisticated. "Rather than mixing perceptibly distinct languages in the same text, it has an ostensible linguistic unity; it is founded on essentially classical Latin structures (especially those of Virgilian poetry) but introduces Latinized dialect and Italian terms with Latin suffixes" (Zancani). This is wordplay of the highest level, deftly combining the classical and vernacular to subtle effect, and one can easily imagine its appeal to a humanist audience. And so the genre feels very much a product of its time, and stands as "a symptom of the retreat of Latin and the rise of the vernaculars" (Smith). ¶ Odasi's Macaronea "is, if not the first, certainly one of the first poetic trials [prove] of a certain scope [respiro] that uses, in a burlesque literary manner, the combination of the courtly structure of the Latin sentence and the expressive vocabulary, sometimes scurrilous, of popular language" (Traversetti). While some have identified a macaronic flavor to certain 13th-century sermons, not until the publication of Odasi's Maraconea did the genre acquire its macaronic moniker. The word is derived from a kind of peasant's dumpling, something not unlike gnocchi today, thus codifying a mix of the humble and low-brow as part of its literary agenda. It's an eminently suitable label, as the genre "cultivates an appropriately 'kitchen' vulgarity of language and content, which it turns to simultaneously ribald and sophisticated ends" (Zancani). True to form, Odasi's burlesque blend of Latin and Italian hexameter follows the hijinks of a group of Paduan students. One episode recounts a prank played on a local apothecary. Another tells of a humble varnisher who believes himself a great painter, even as his clients sue him for shoddy work. And one near the end contains a rather sexually graphic allegory, though the macaronic language spoils our own translation efforts (see Barbara Spackman's citation if you're curious). Indeed, given its inherent reliance on the relationships between multiple languages, there's something fundamentally untranslatable about the genre. ¶ Our type is Silber's 109R, a roman font with a twenty-line measurement of ~109 mm, in use from 1485 to 1506. BM XV identifies three different states of this type. In its third state, a short, narrow, more upright virgule was introduced in 1498; we also find a taller version of the more upright virgule used through 1493; and we find no narrow virgules used 1494-1495 (no digitized 1496-1497 imprints were available to us, and with the obvious caveat that what's been digitized does not represent Silber's complete corpus). Our verse required far less punctuation, but we do find a single wide virgule in the middle of the final line on a2v. When used, the narrower virgule was by far the preferred form for medial positions, our wider form typically reserved for line endings. Our paucity of punctuation makes for slight evidence, but this slight evidence does support dating our edition between 1493 and 1498. We can more reliably identify 1499 as a terminus ante quem, by which point the type appears to have replaced its small [us] abbreviation, resembling a superscript 9, with a full-size form that sits on the baseline. Close observers may notice that our [us] does not match the version commonly found in type 109R, which appears cocked slightly counterclockwise compared to ours. We find our version in only two other imprints using type 109R, in 1492 and1498. ¶ The decorative initials provide a second data set that may assist dating. Our lombardic H on a3v, for example, is also found in Silber's 1493 edition of Verardus's Historia Baetica (p. 41 of the digital scan), and our A (c1r) in a Silber imprint of 16 February 1496. Given the vagaries of inking and occasional interference of adjacent type, assessing the condition of these small blocks can be difficult, absent an obvious crack. But we think our initials appear slightly more worn than in the 1493 and 1496 imprints. In short, we consider 1493-1499 to be the widest likely date range, with traces of evidence pointing to ca. 1497. We prefer slightly later than 1493 for the woodcut, too, after the dart border and the black ground with bits of white foliage had become more common. ¶ Very rare in any edition. We find no auction records for any editions, and no copies of any edition in North America.

PROVENANCE: With four brief early marginalia, simply the one- and two-word wayfinding variety, and a number of early non-verbal markings.

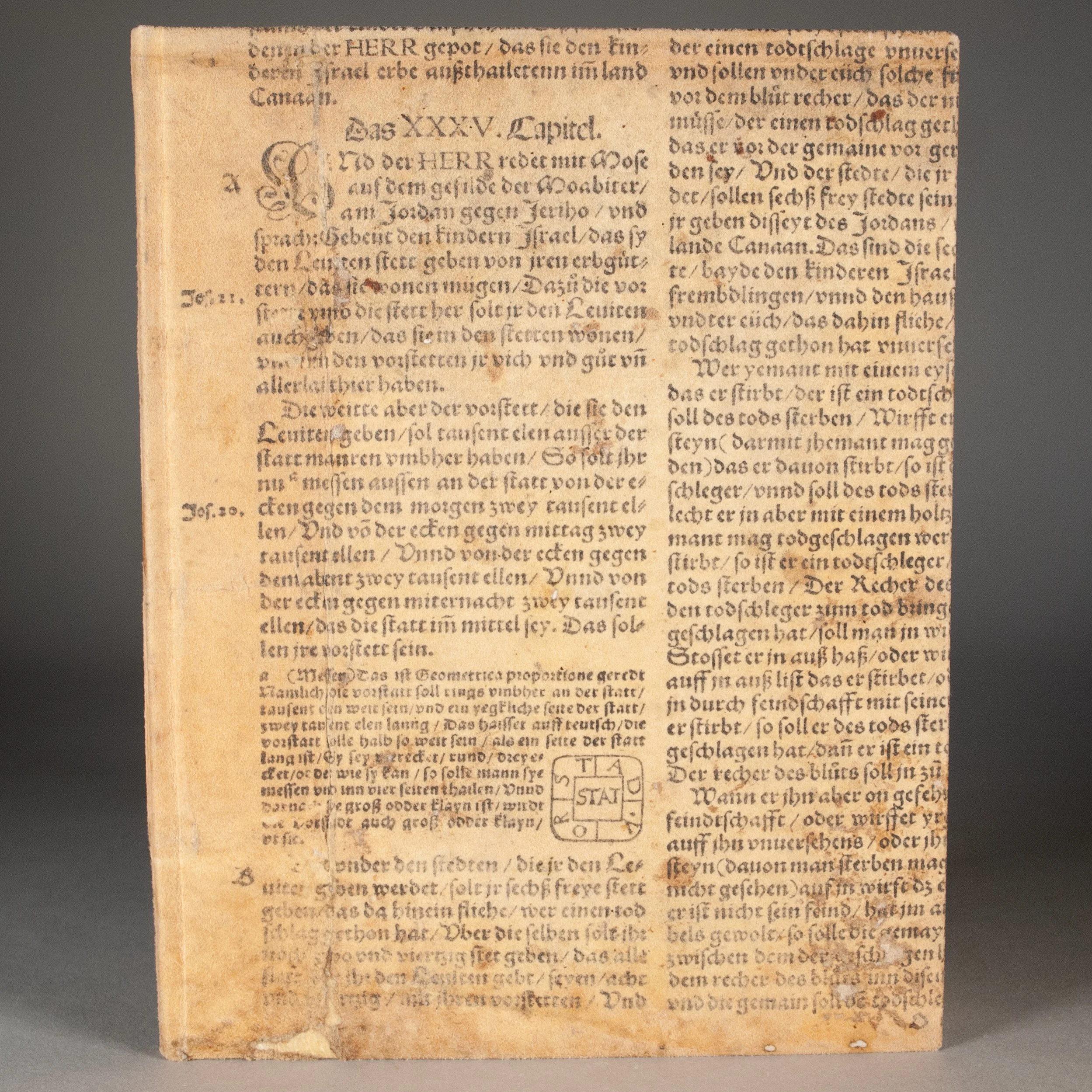

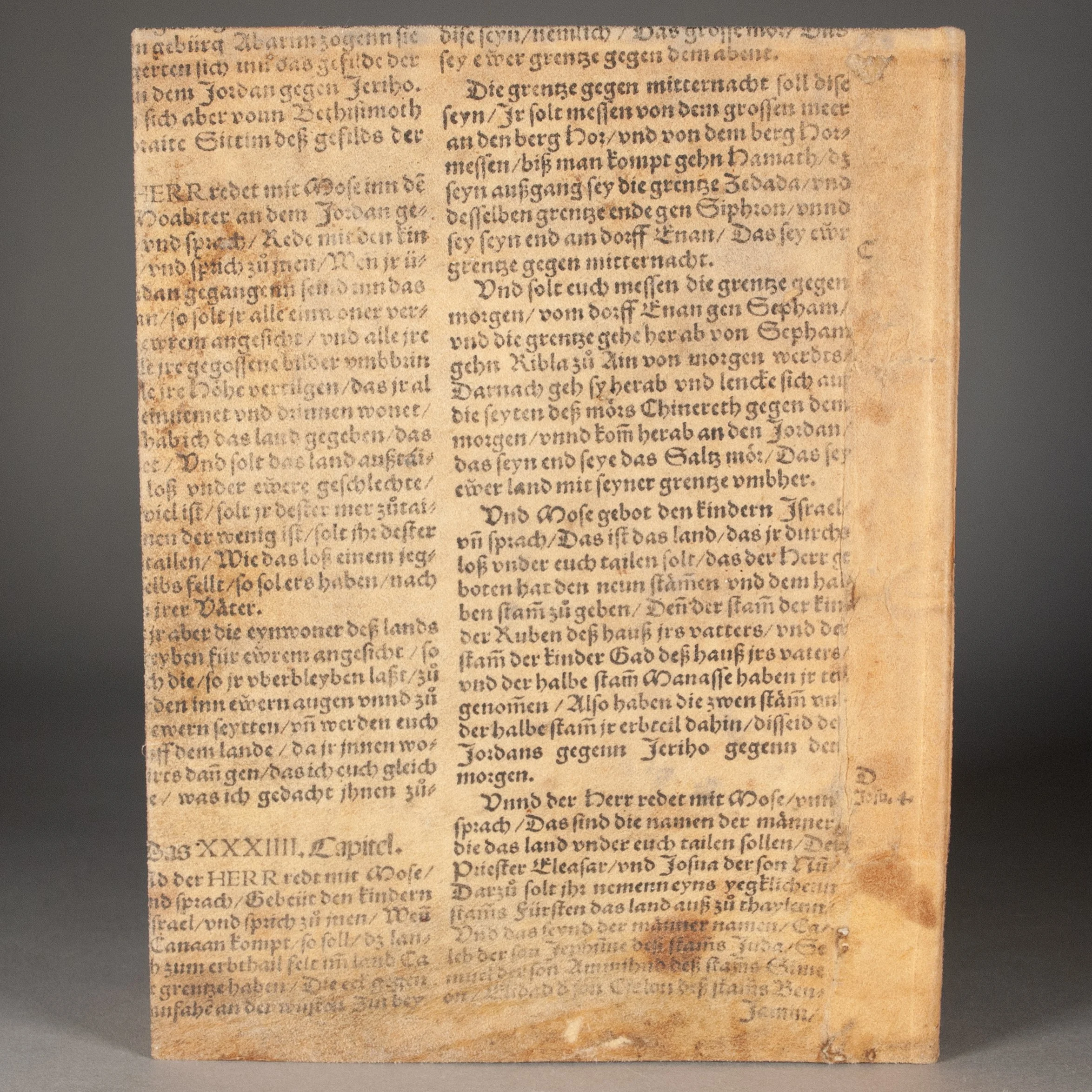

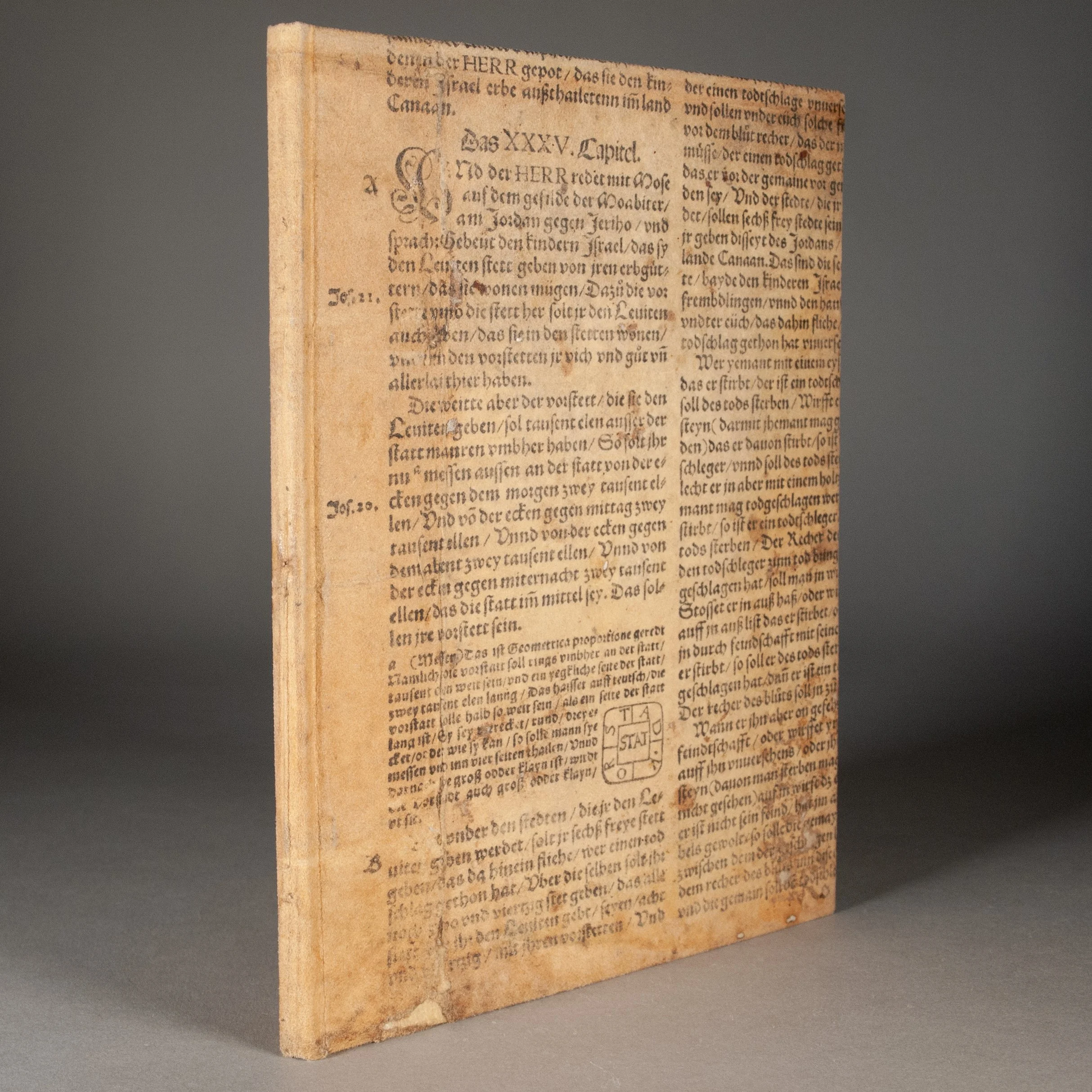

CONDITION: In a 20th-century binding using leaf O3 from a vellum copy of Heinrich Steiner's famed 1535 Bible—not only a tour de force of book production, but just the second complete edition of Luther's German translation. Old damage suggests this is the leaf's second time used in a binding. Illustrated with a half-page woodcut on the first leaf, characteristically Italian with its dart border. We've been unable to trace it elsewhere, save for its use in the Silber edition held by the Palatine Library in Parma. Decorated throughout with eight woodcut lombard initials, several of which we've found in other Silber imprints. We rather love how the printer roughed up a decorative E to serve as an F for the opening line. Perhaps with a faint watermark, lost in the gutter. ¶ First and last page a bit dusty, but really in remarkable shape, even preserving some deckle edge. The German Bible leaf soiled, with some hard creases from prior use in binding, and old losses mitigated by plain parchment underneath.

REFERENCES: On the content: Paul Gerhard Schmidt, "The Quotation in Goliardic Poetry," Latin Poetry and the Classical Tradition (1990), p. 55 (cited above); Bruno Traversetti, Cronistoria della poesia italiana (2005), p. 64 (cited above; "The poem acquired further significance for having served as a direct model for the macaronic works of Teofilo Folengo"); Erin McCarthy-King, "The Voyage of Columbus as a 'Non Pensato Male': The Search for Boundaries, Grammar, and Authority in the Aftermath of the New World Discoveries," New Worlds and the Italian Renaissance (2012), p. 27 ("Just two years before Columbus's famous first voyage, Tifi Odasi writes the Macharonea and with it, canonizes a new literary 'language' named thereafter macaronic"); Fred C. Robinson, "'The Rewards of Piety': Two Old English Poems in Their Manuscript Context," Hermeneutics and Medieval Culture (1989), p. 196 (on "The Phoenix"); Laurent Paya, "Les livres de modèles de broderies du XVIe siècle, et la résolution de conflits esthétiques par la mescolanza," Management and Resolution of Conflict and Rivalries in Renaissance Europe (2023), p. 269n10 (noting the work "attacks Paduans suspected of practicing magic"); Letizia Panizza, "Odasi, Tifi," The Oxford Companion to Italian Literature (2005; "the first example of a macaronic poem and the source of the term"); Diego Zancani, "Macaronic Literature," Oxford Companion to Italian Literature (2005; cited above; "An early practitioner, and the originator of the founding image, if not of the practice of macaronic writing"); Barbara Spackman, "Inter musam et ursam moritur: Folengo and the Gaping 'Other' Mouth," Refiguring Women (1991), p. 21 (for an English translation of an excerpt from c1v-c2r); Diletta Gamberini, "The Fiascos of Mimesis: Ancient Sources for Renaissance Verse Ridiculing Art," Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 63.1 (2021), p. 75-76 (for an summary of the painter episode) ¶ Bibliographical: Octave Delepierre, Macaronéana, ou, Mélanges de littérature macaronique (1852), p. 128 (describing the Parma copy); "Type 4:109R bei Eucharius Silber," Typenrepertorium der Wiegendrucke (conspectus of all recorded imprints using Silber's type 109R); Catalogue of Books Printed in the XVth Century Now in the British Museum (1916), pt. 4, p. 103 (on the three states of Silber's type 109R, though our own observations suggest it may be more complicated); A Heavenly Craft: The Woodcut in Early Printed Books (2004), p. 98, #13 (for a Roman woodcut, ca. 1492-1493, also using a dart border); Stanley Morison, The Typographic Book 1450-1935 (1963), p. 27 (“It was not until Stephan Plannck and Eucharius Silber set up their presses in 1480 that Rome acquired printers able to rival the highest quality then achieved elsewhere in the peninsula")

Item #864