Acting manual annotated by pianist

Acting manual annotated by pianist

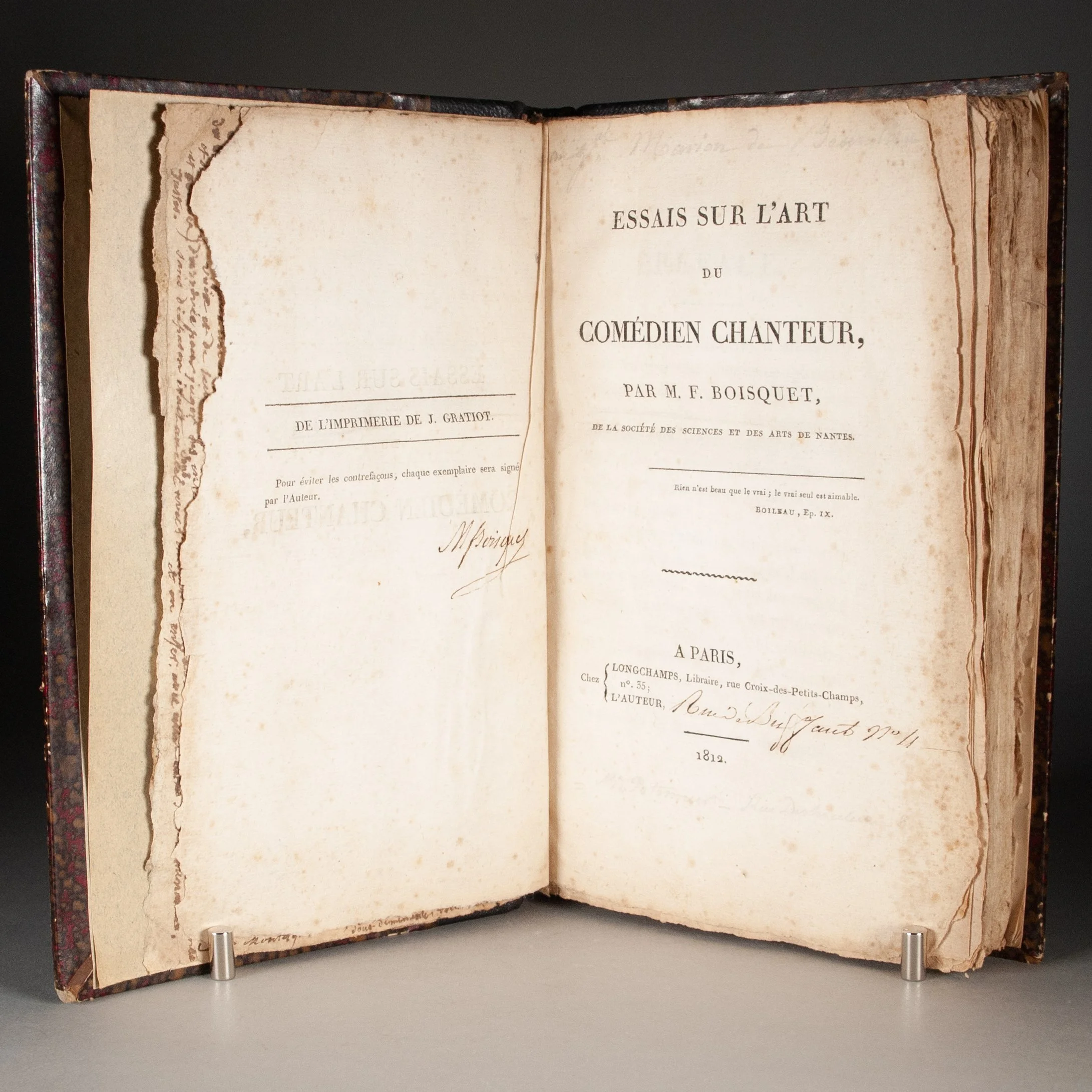

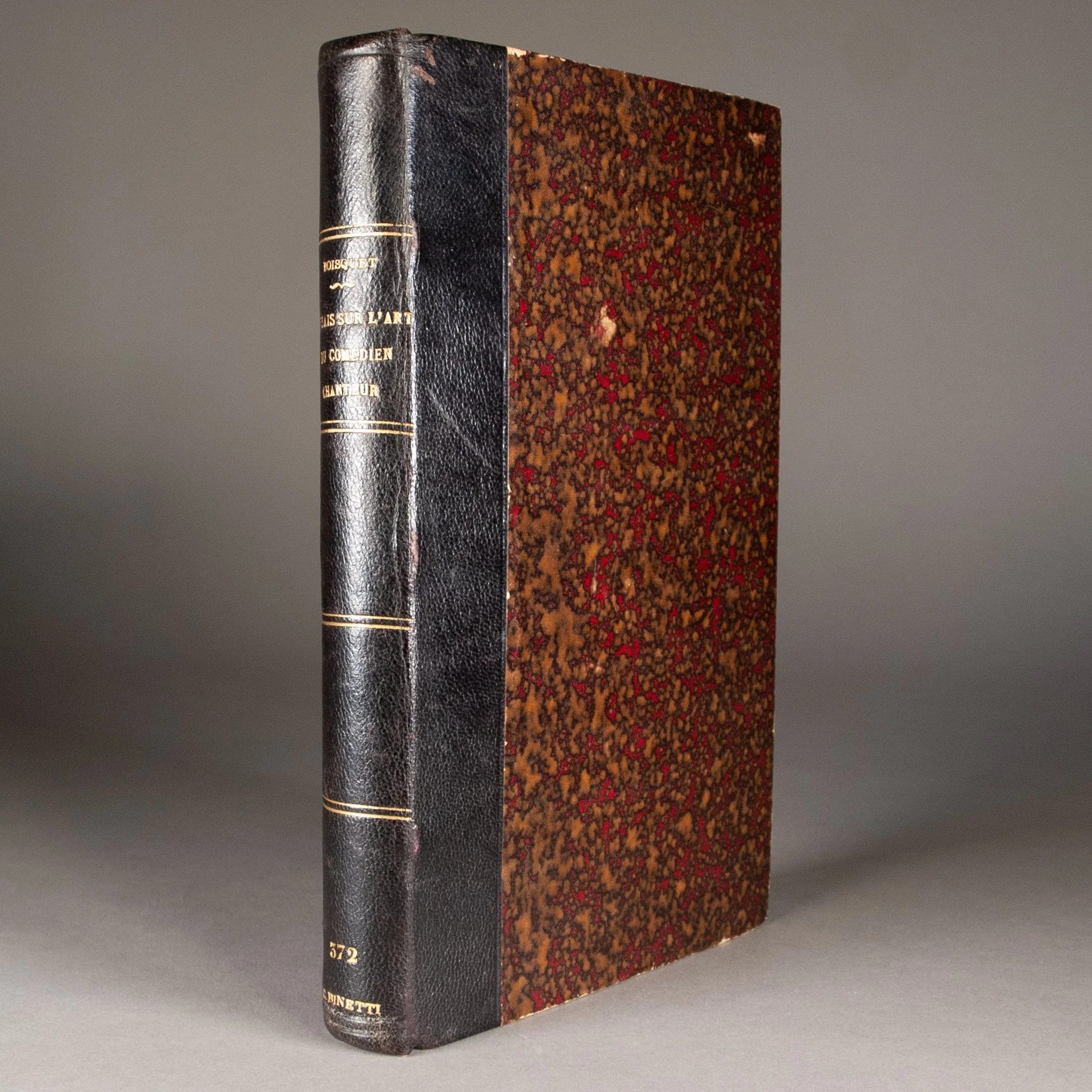

Essais sur l'art de comédien chanteur

by François Boisquet

Paris: Longchamps and the author, 1812

[4], 296 p. | 8vo | pi^2 1-18^8 19^4 | 208 x 137 mm

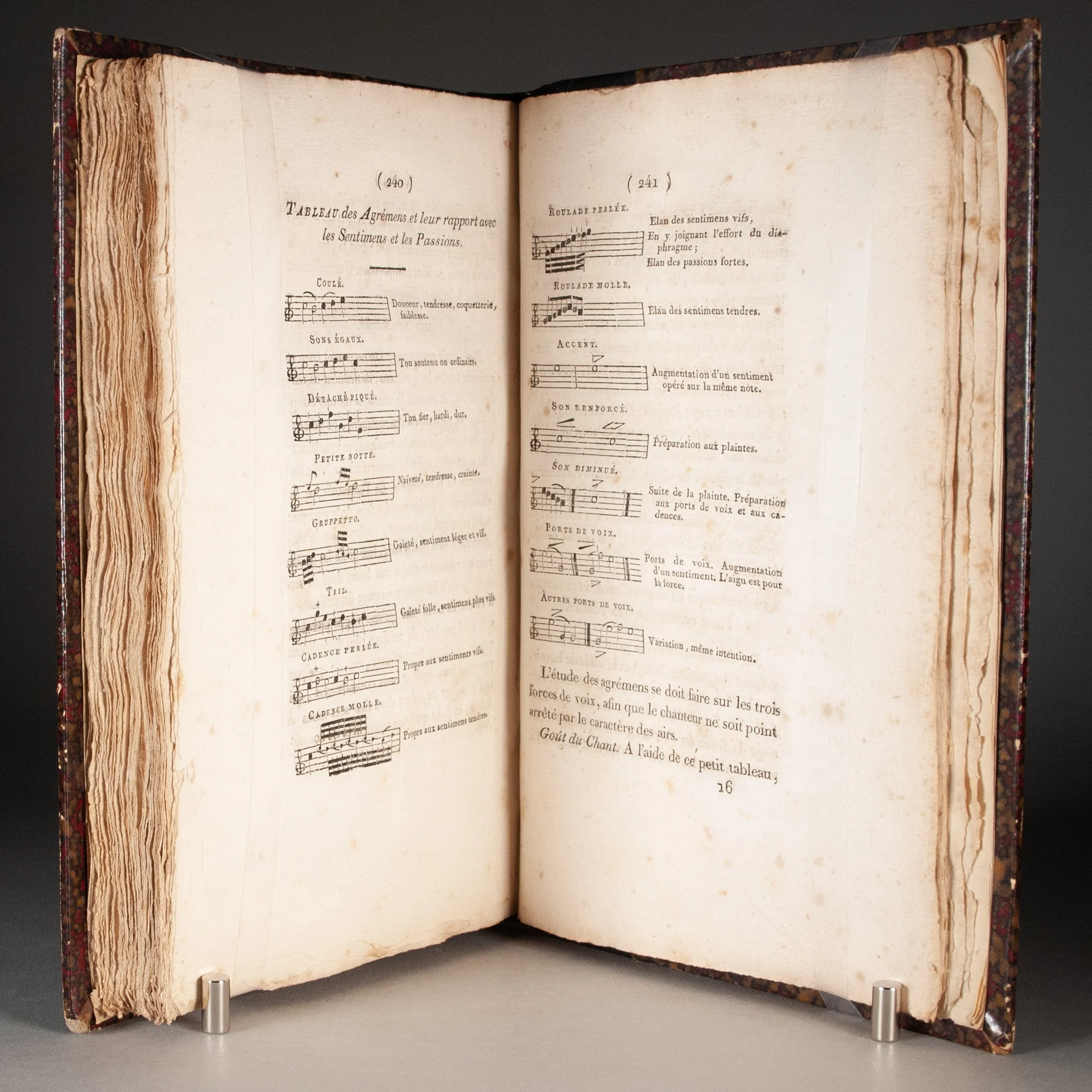

First and only edition of this manual for singing actors. The book must have appealed not only to those pursuing traditional opera, and perhaps those interested in the more fashionable genre of melodrama, but our annotations suggest it may have appealed just well to those with no interest in acting at all (more on that below). ¶ The book is divided into four broad divisions: singing, acting, pantomime, how to use the voice in these acting roles, and a final brief section with more philosophical reflections and macro-level observations on acting and singing. The author delves into both the theory and the mechanics of these many skills, frequently in great detail. He discusses different types of sounds, the best ways to breathe, and why singers lose their voices. He explores the characteristics of different roles, a section packed with sweeping generalizations about all kinds of people. People from warm climates, for example, have a lively intelligence; the French excel in physical exercise, and love both the arts and the sciences; and women in countries prone to despotism are either recluses or slaves. Utility as a performer's handbook aside, these forty pages offer a fascinating roster of stereotypes prevalent at the time. We suspect they may have benefited players of melodramatic characters especially, which were seldom written with much depth. The coverage is truly exhaustive for the aspiring performer. ¶ In England at least, the history of the acting manual typically begins in the 18th century with Charles Gildon's Life of Mr. Thomas Betterton (1710), and Dufresnel's Essai sur la perfection du jeu théâtral (1782) is commonly cited as an early Francophone contribution to the genre. Throughout the 18th century, similar instructional content might also be found in memoirs by prominent actors, and even in the growing corpus of theatre journalism. Still, even in the early 19th century, manuals like this weren't exactly thick on the ground. "Unfortunately," Gabrielle Hyslop writes, "bibliographical research so far has unearthed very few dictionaries and manuals dating from the early decades of the century." Boisquet's manual appeared at a dynamic time for theatre, just as melodrama was growing in popularity, and so his section on pantomime—a critical element of melodrama—may have been especially valuable. ¶ We find a single copy in North America (University of North Texas).

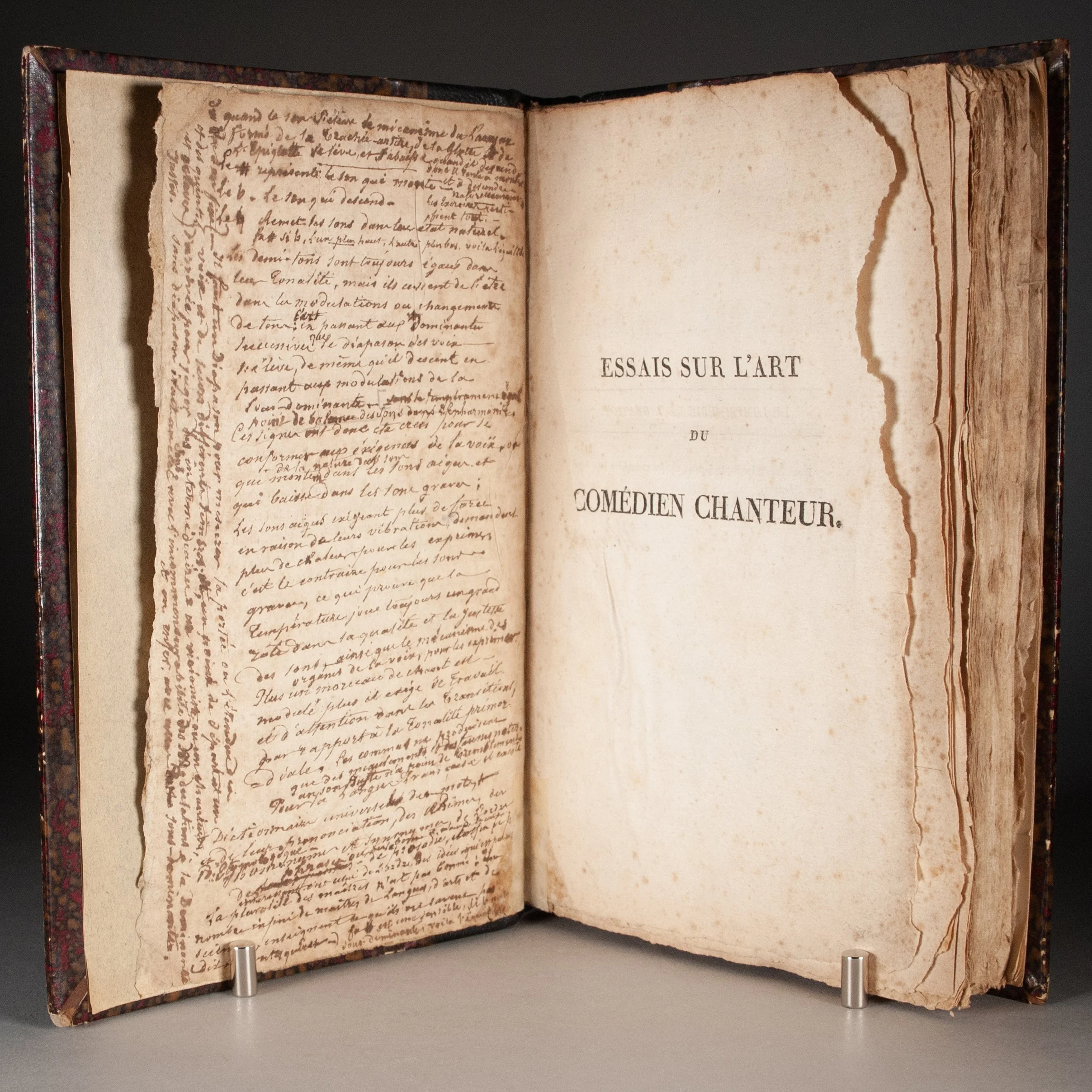

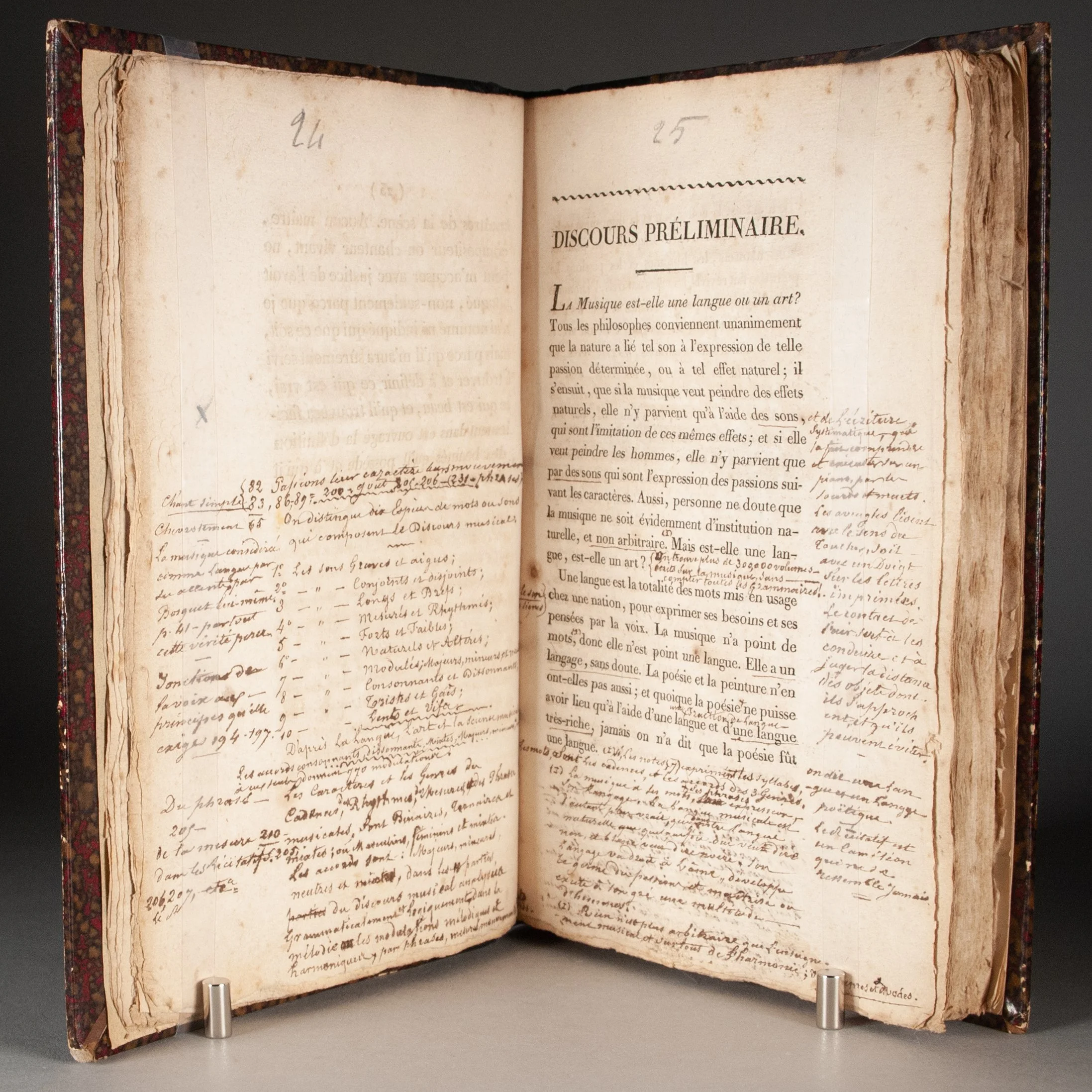

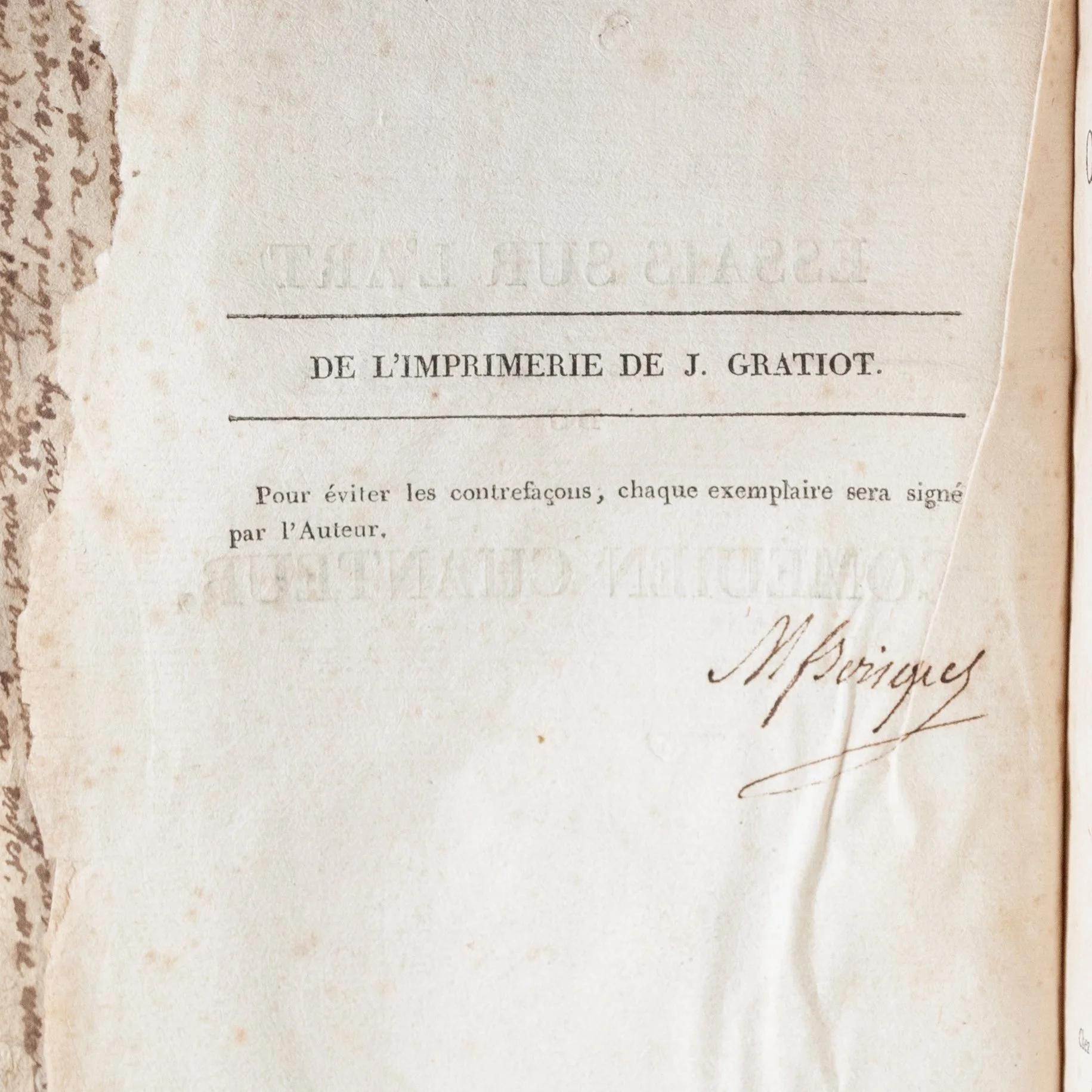

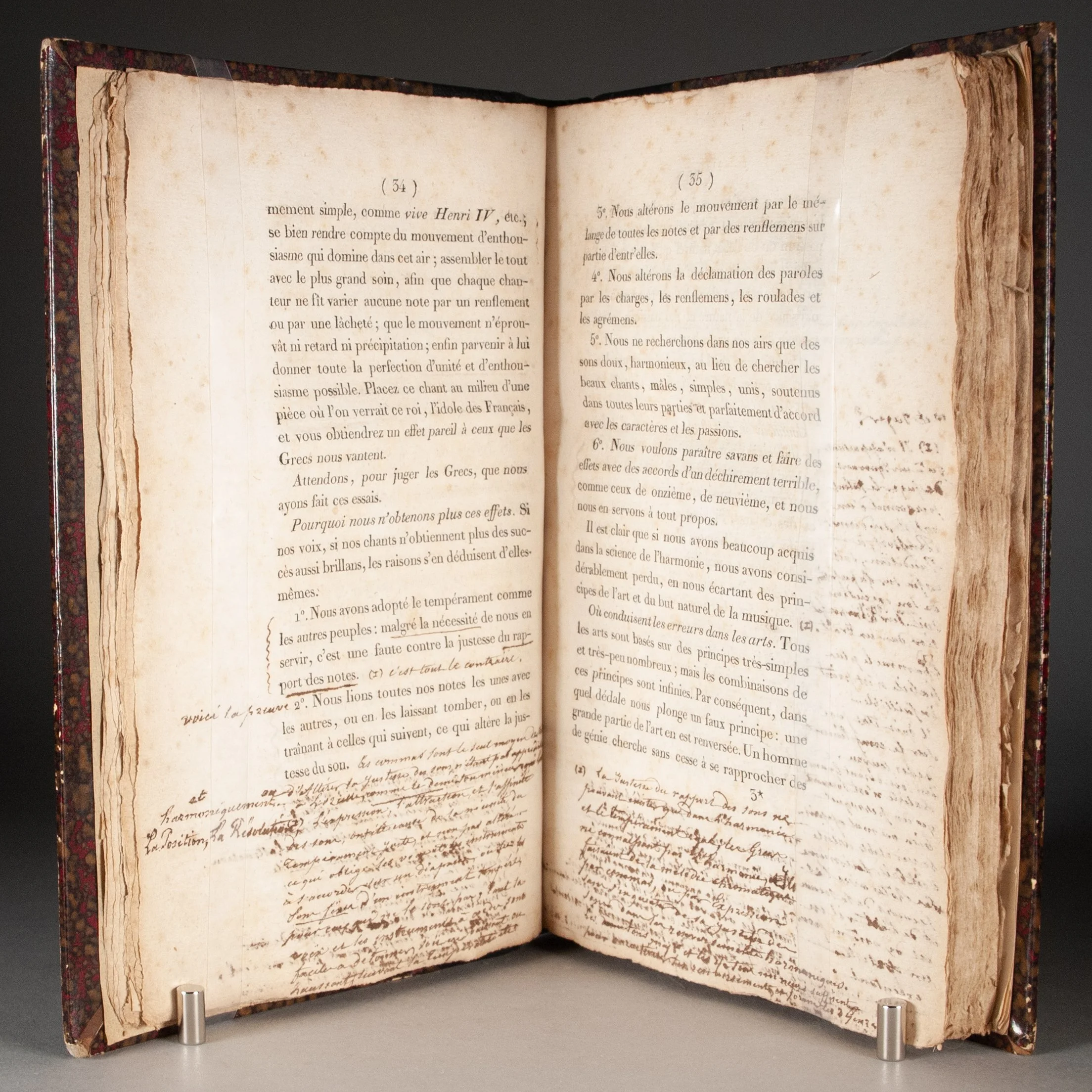

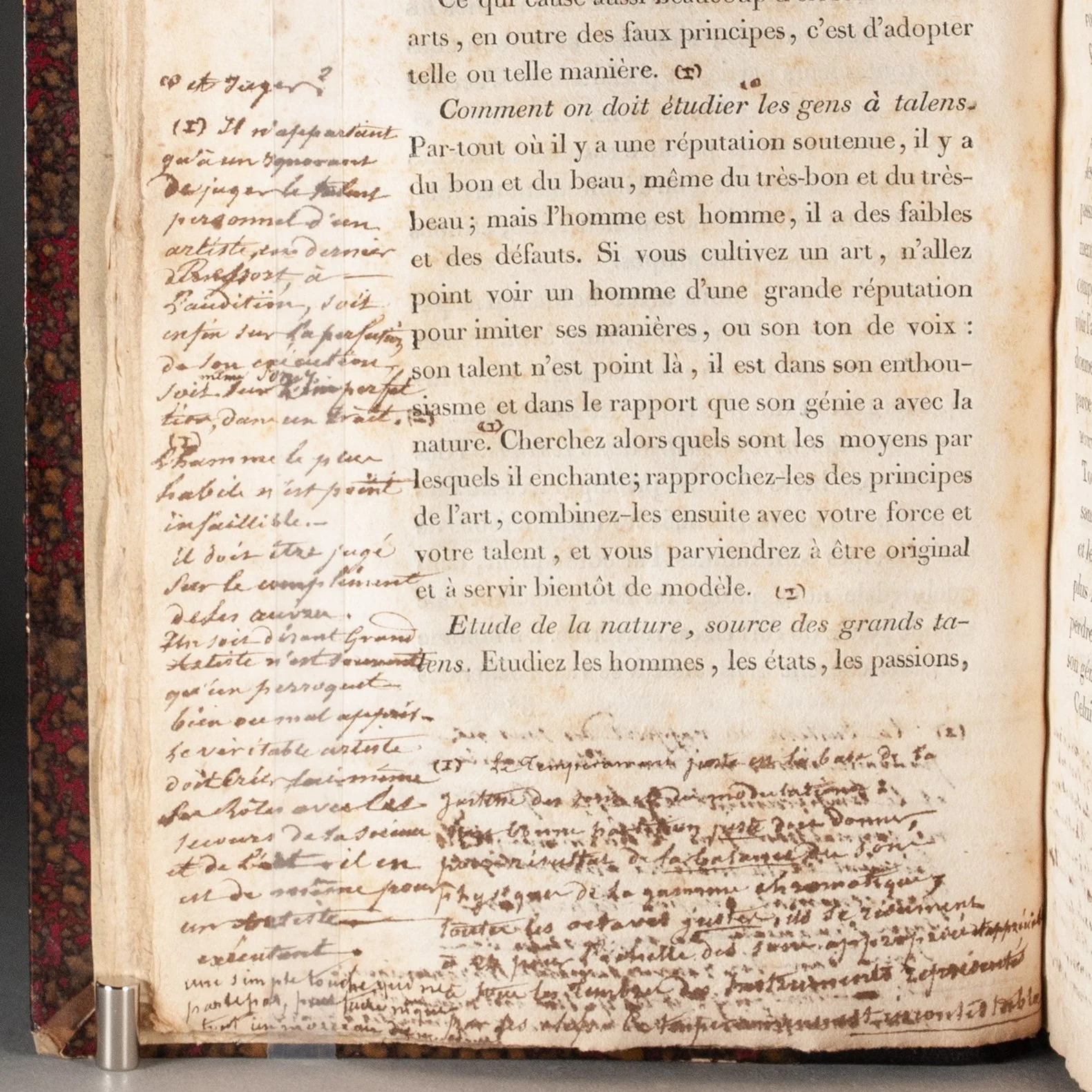

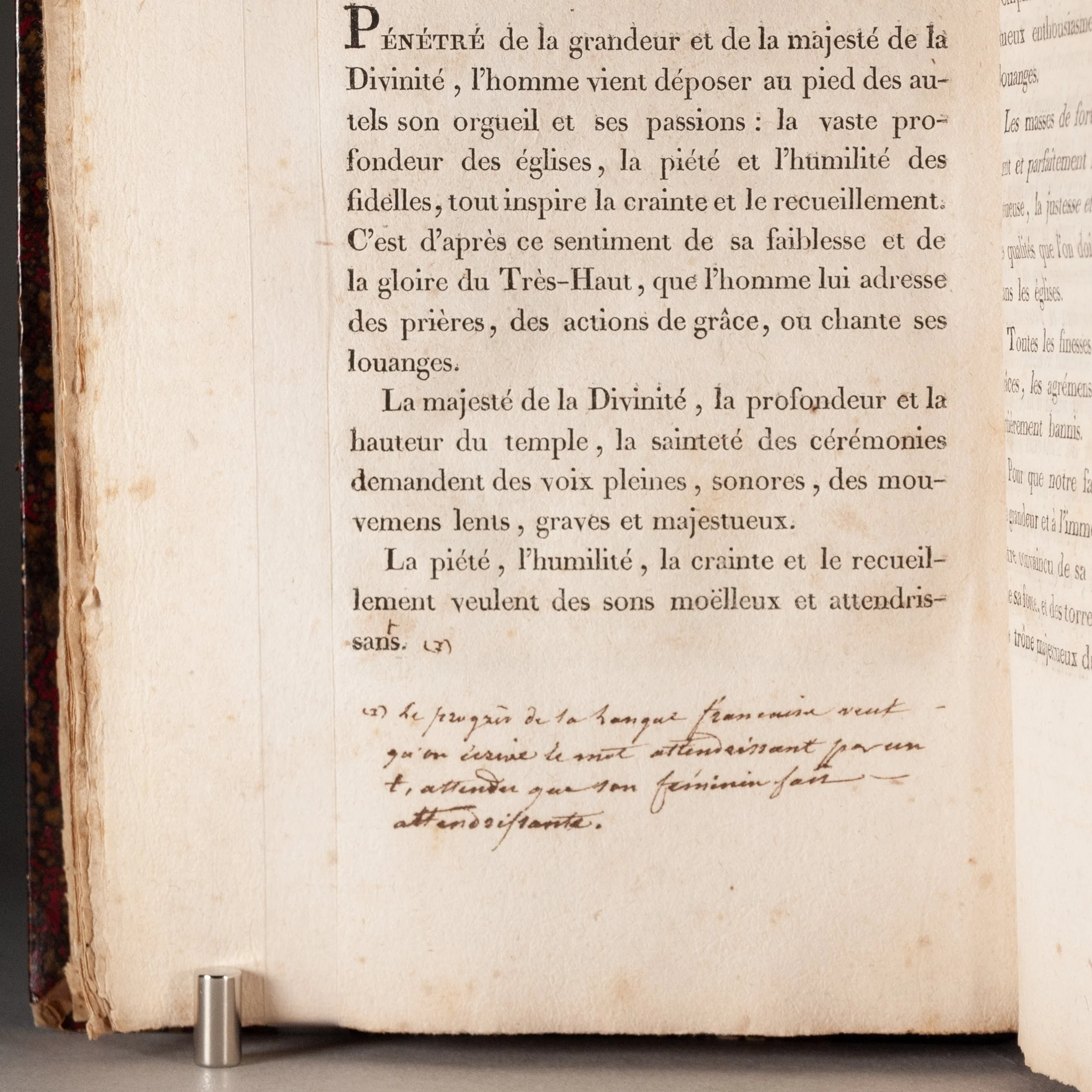

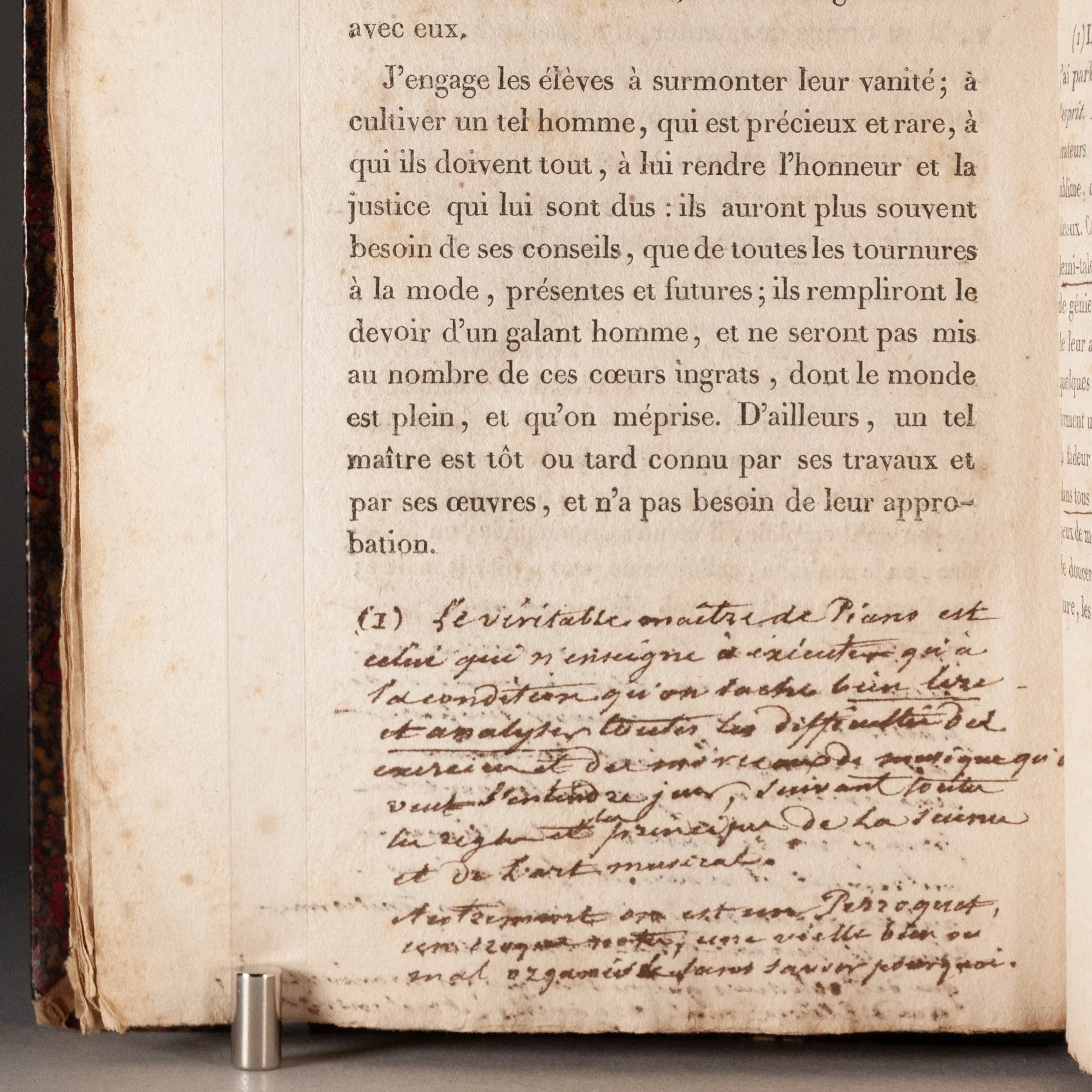

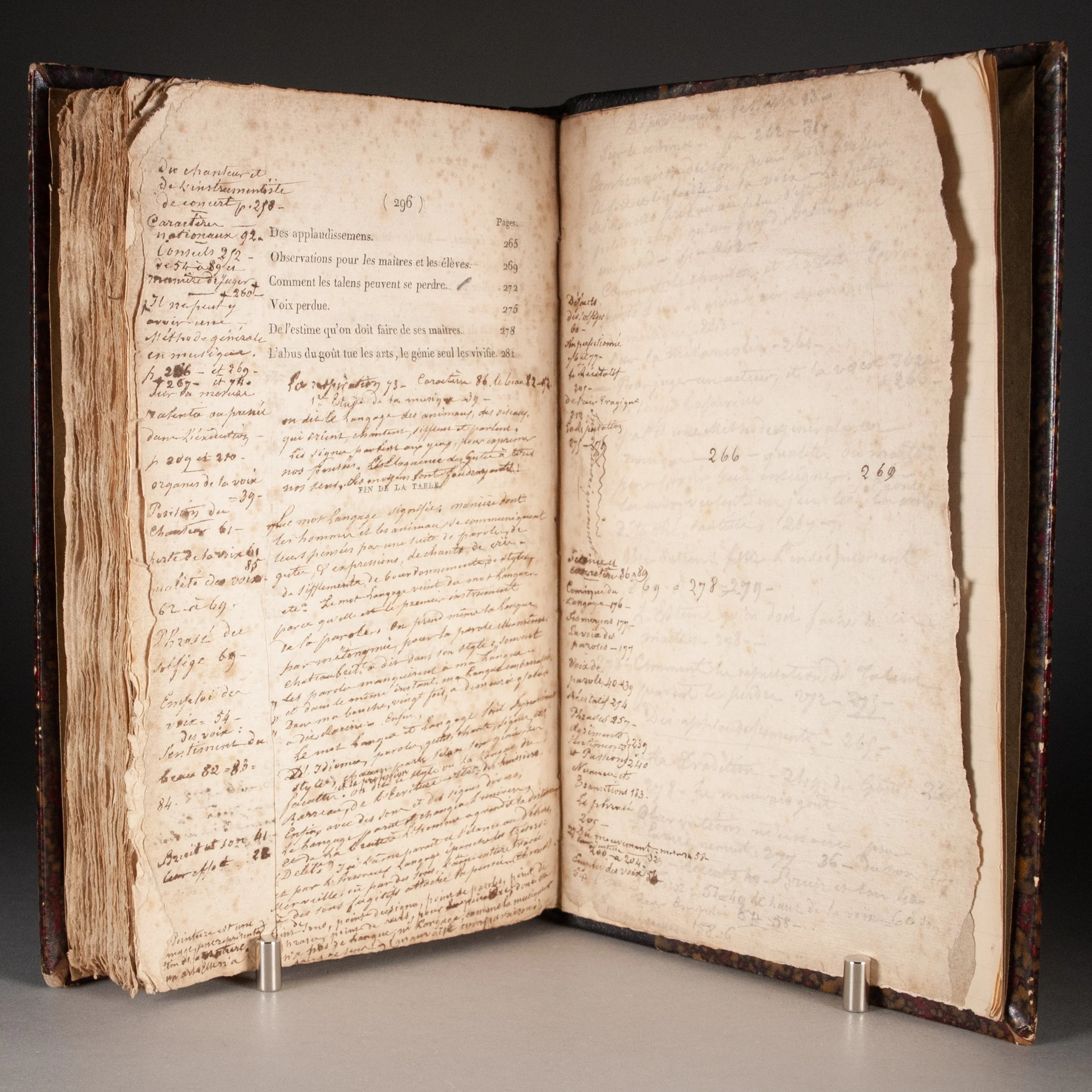

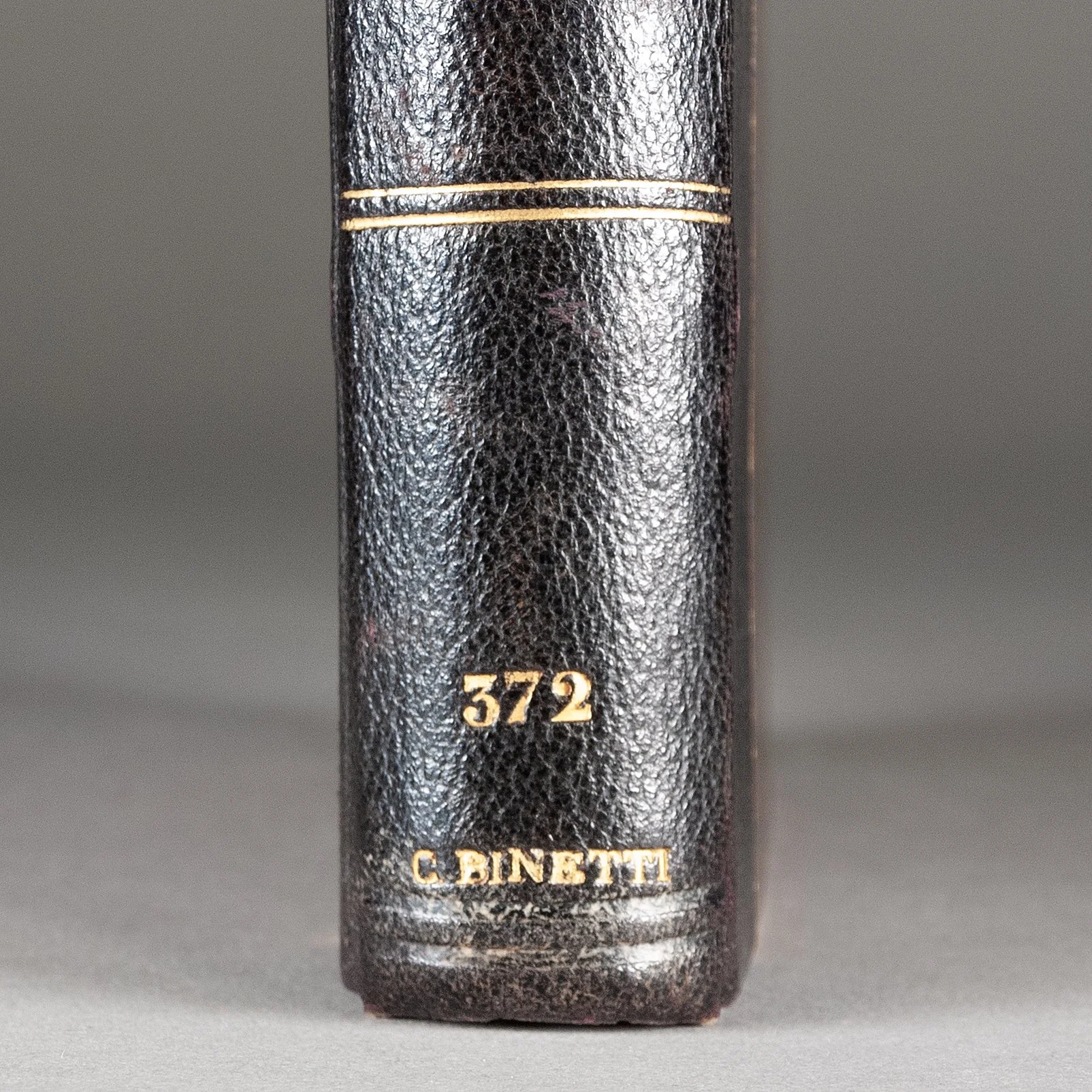

PROVENANCE: With scattered and very heavy annotations in an early hand, adding perhaps a few thousand words of manuscript material. While the index scribbled across the final two leaves points to some engagement with the chapters on acting, the annotations overwhelmingly focus on music, and evidence suggests our annotator was likely a pianist. In a footnote on p. 279, Boisquet touches on the tension that can arise when a student surpasses his teacher. Our annotator goes on to explain what it's like pour un professeur de piano. On the following page, Boisquet expands on what it means to be a true master singer, here mentioning no instrument other than the voice. Our reader responds in the lower margin not with their thoughts on mastering voice, but on what it means to be a true master of piano (véritable maître de piano). ¶ The inside front cover of the original wrapper is densely packed with notes on the nature of sound, indicating, among other things, "that temperature always plays a big role in the quality and the accuracy of sounds" (que la température joue toujours un grand role dan la qualité et la justesse des sons). Our reader clearly took a keen interest in the opening section ("Is music a language or an art?"), and here (as elsewhere) betrays a close reading of Boisquet's text, cross-referencing passages scattered throughout the rest of the work. Our reader has added many of their own lengthy footnotes, which invariably expand upon the printed text, and is not afraid to argue with Boisquet—a refreshing departure from the blind deference to authority we find in so many 15th-, 16th-, and 17th-century annotated books. For example, where Boisquet starts to explain why today's singers cannot match the quality of those in centuries past, our annotator interjects: "It's quite the opposite" (c'est tous la contraire), they write, and provide an explanation in their own footnote on the following page. And sometimes they're just petty. On p. 256, our annotator corrects the final letter of Boisquet's attendrissans, with an explanation that "the progress of the French language demands that we write the word attendrissant with a t." We come away with the feeling that our reader may have been a greather authority on music than Boisquet. ¶ With the author's signature on the half title verso—confirming this an authorized copy, not a pirated one—and with his street address added by hand to the imprint. ¶ Faint French name and address penciled at foot of title page, and another name penciled at head of title (Marion de...). The name C. Binetti stamped at the foot of spine, perhaps that of French composer Camille Binetti (1851-1930).

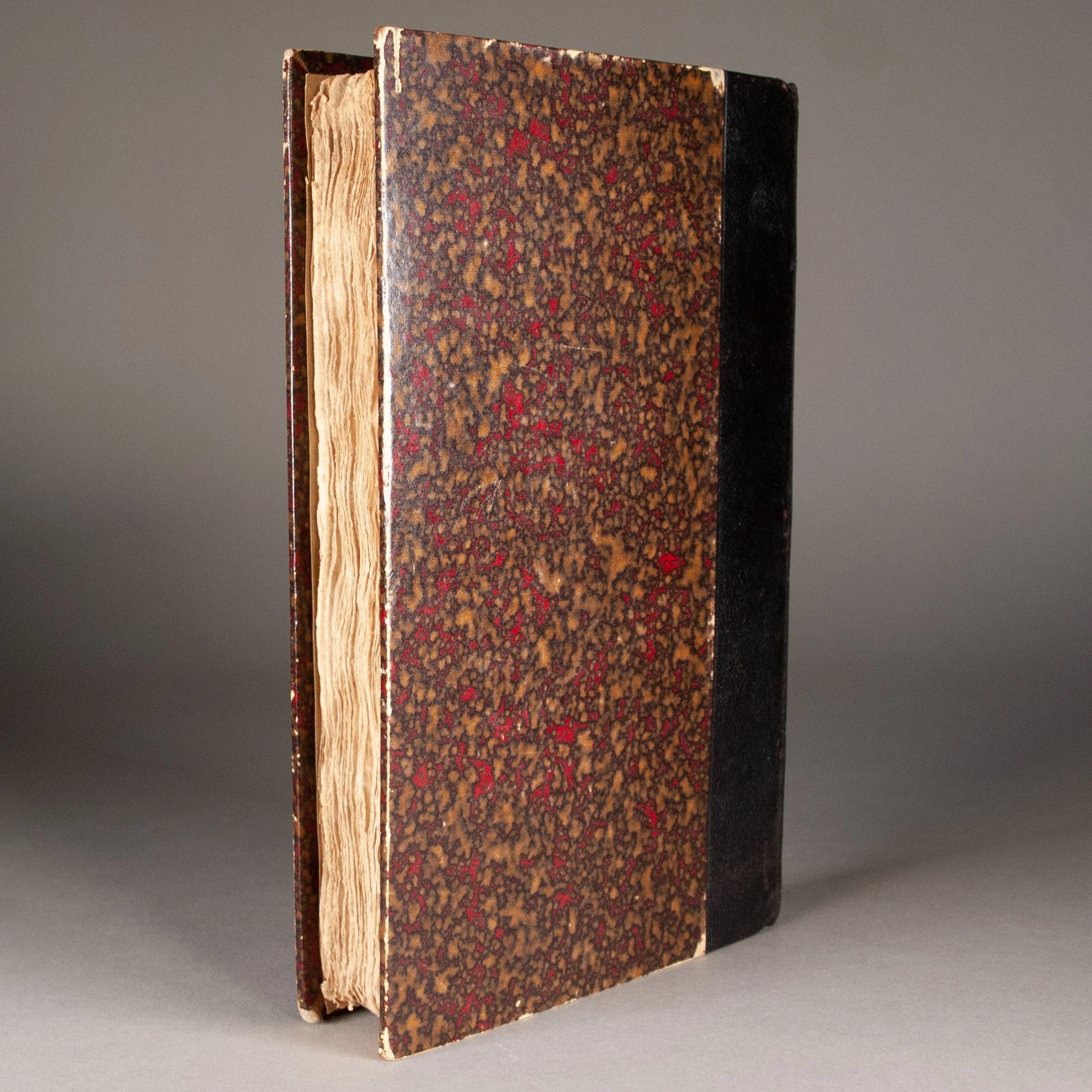

CONDITION: In later quarter black leather and dark marbled boards, preserving the book's original paste-paper wrapper, likewise its deckle edges; four leaves of lined paper bound in at end. With occasional snippets of notated music throughout. ¶ First and last few leaves a bit tattered at the edges; last few leaves repaired at the inner margin, one of them with a small repaired tear in the bottom edge; mild foxing throughout. Binding just a bit rubbed at the extremities.

REFERENCES: Gabrielle Hyslop, "Researching the Acting of French Melodrama, 1800-1830," European Theatre Performance Practice, 1750-1900 (2014; unpaginated ebook), "3. Newspaper reviews and articles" (suggesting melodrama was still fairly novel in the earliest years of the 19th century, its reputation "already firmly established" by 1815), "4. Theatrical dictionaries and acting manuals" (cited above); Sarah E. Chinn, Spectacular Men: Race, Gener, and Nation on the Early American Stage (2017), p. 32 (specifically within an Anglo-American context: "While acting manuals did not emerge until the early eighteenth century, explorations into the meanings of performance had existed for at least a century before then, although seventeenth-century thinkers analogized acting and oration more closely than their later counterparts"); Lisa Zunshine, Acting Theory and the English Stage, 1700-1830 (2008), unpaginated ebook, "General Introduction" (useful summary of the acting manual in 18th- and 19th-century England)

Item #753