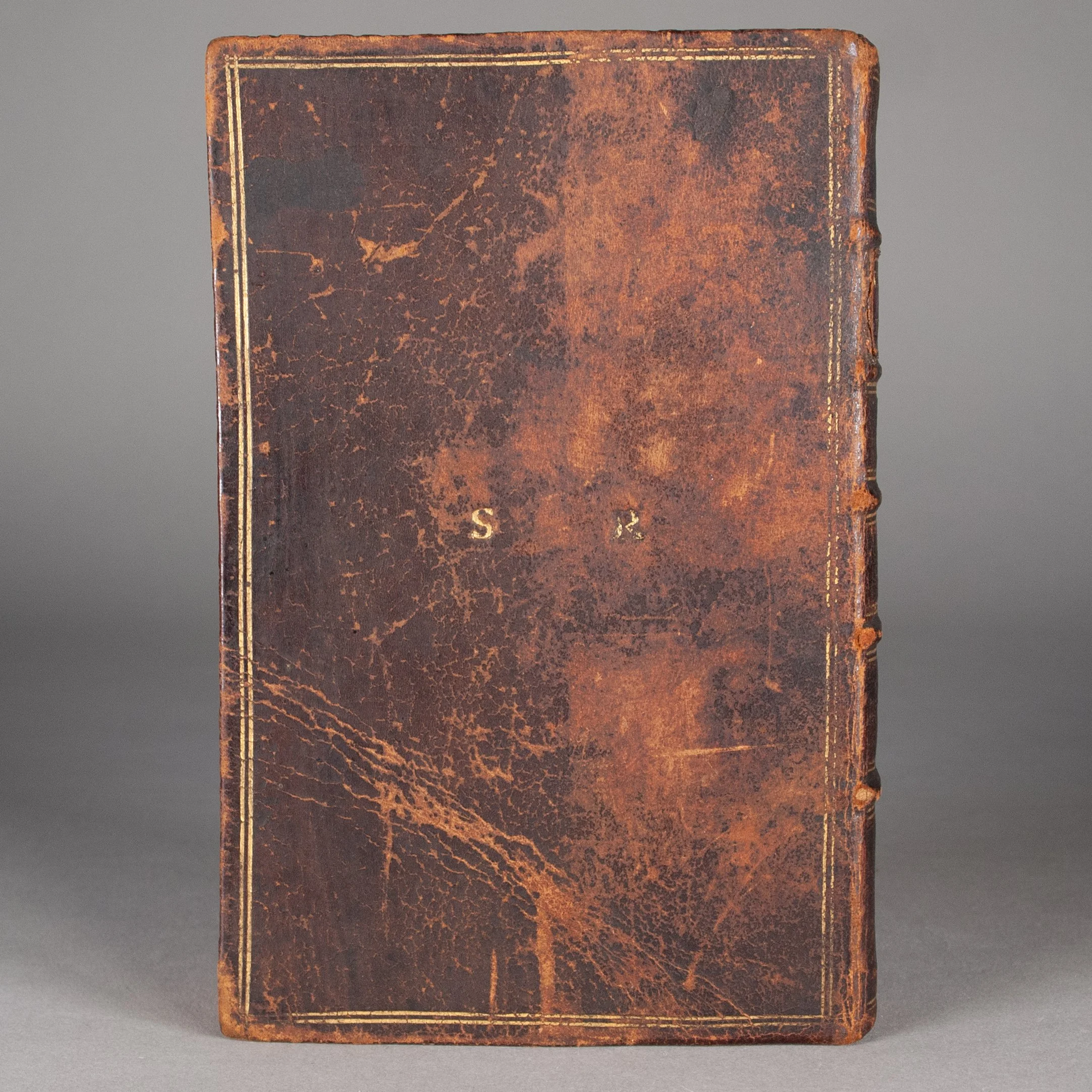

Very early American gilt binding | Sarah Ruggles's copy

Very early American gilt binding | Sarah Ruggles's copy

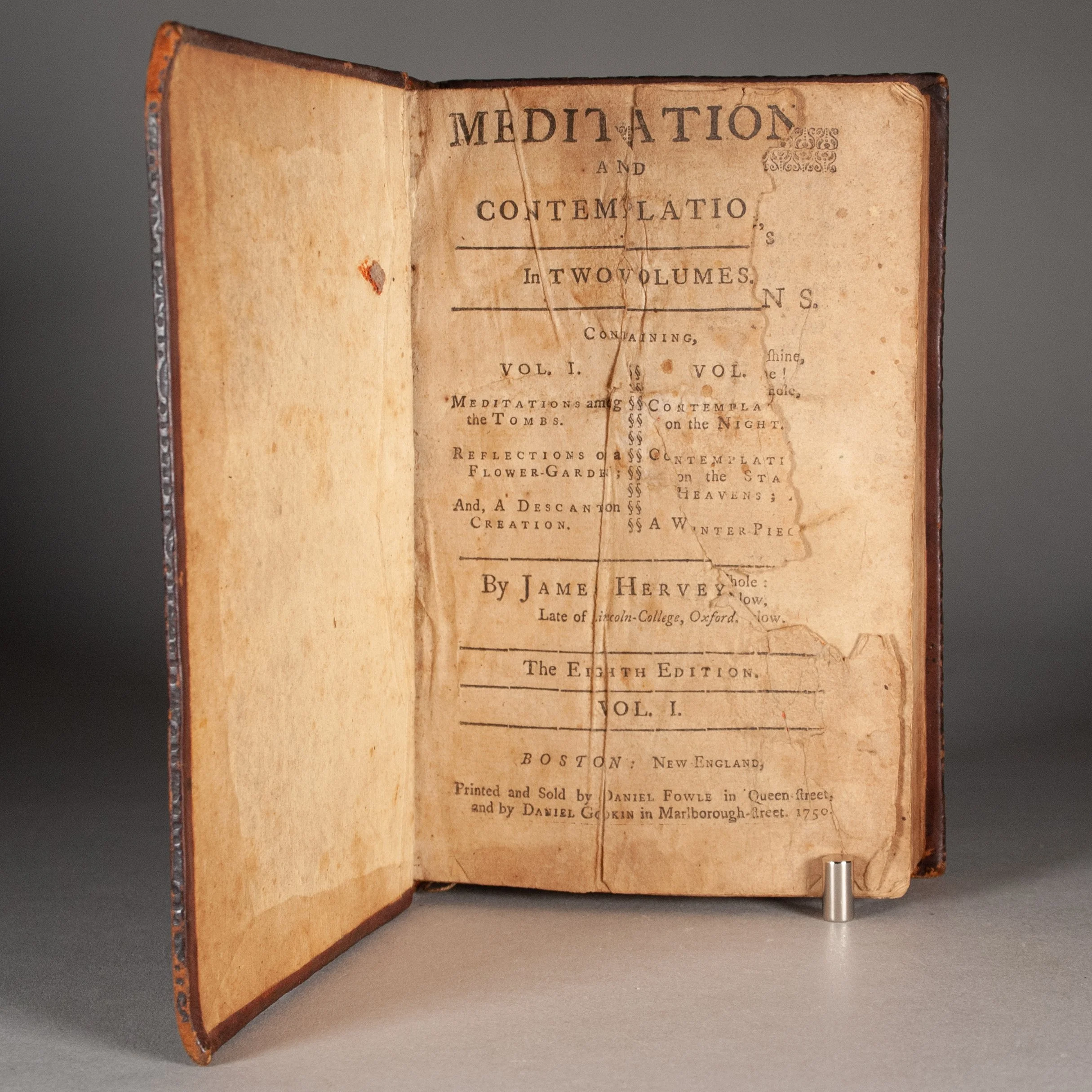

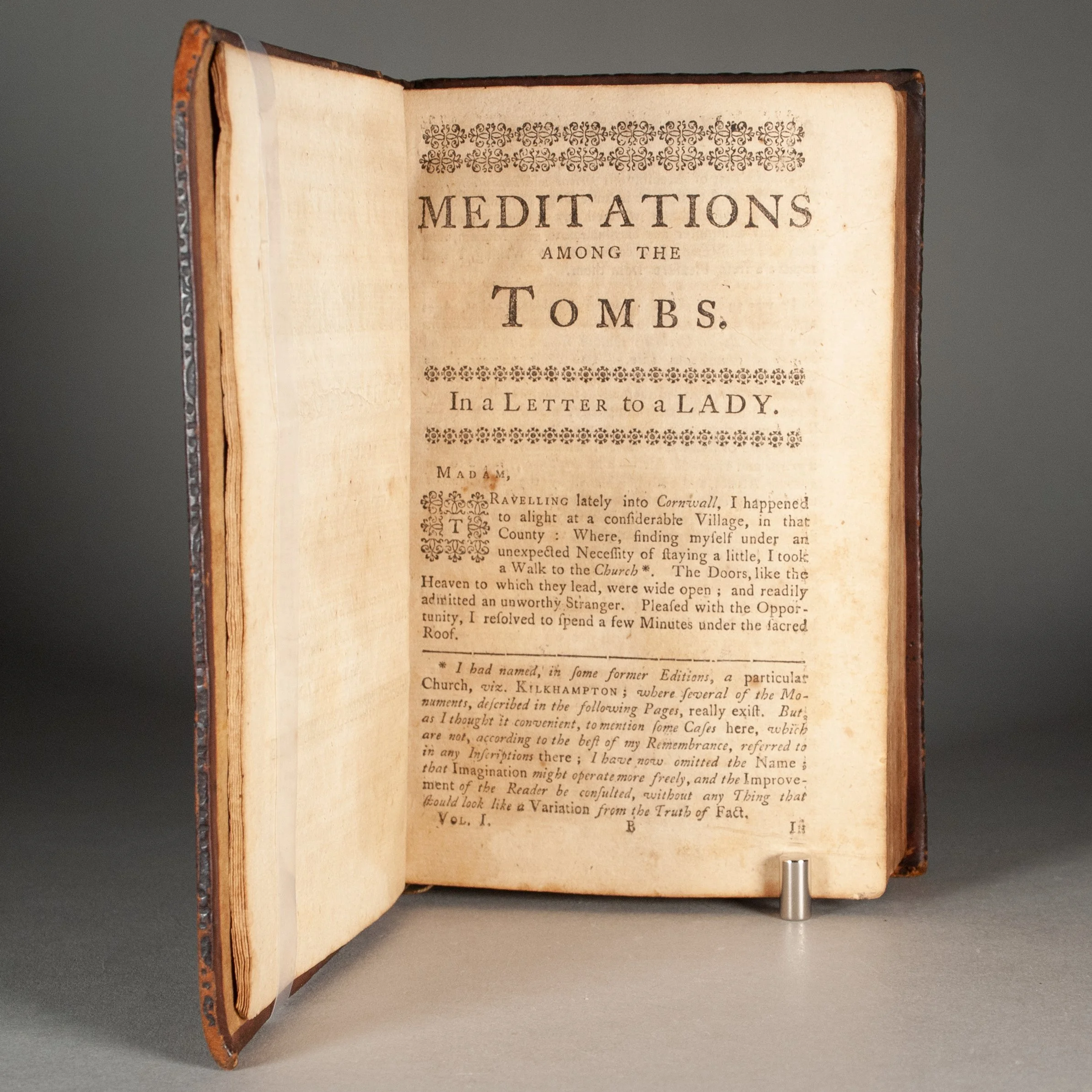

Meditations and contemplations, in two volumes, containing, vol. I: meditations among the tombs; reflections on a flower-garden; and, a descant on creation; vol. II: contemplations on the night; contemplations on the starry heavens; and, a winter-piece

by James Hervey

Boston: Daniel Fowle and Daniel Gookin, 1750

xiv, [2], 200; xiv, [2], 197, [3] p. | 8vo | A-N^8 O^4; A-N^8 O^4 | 164 x 130 mm

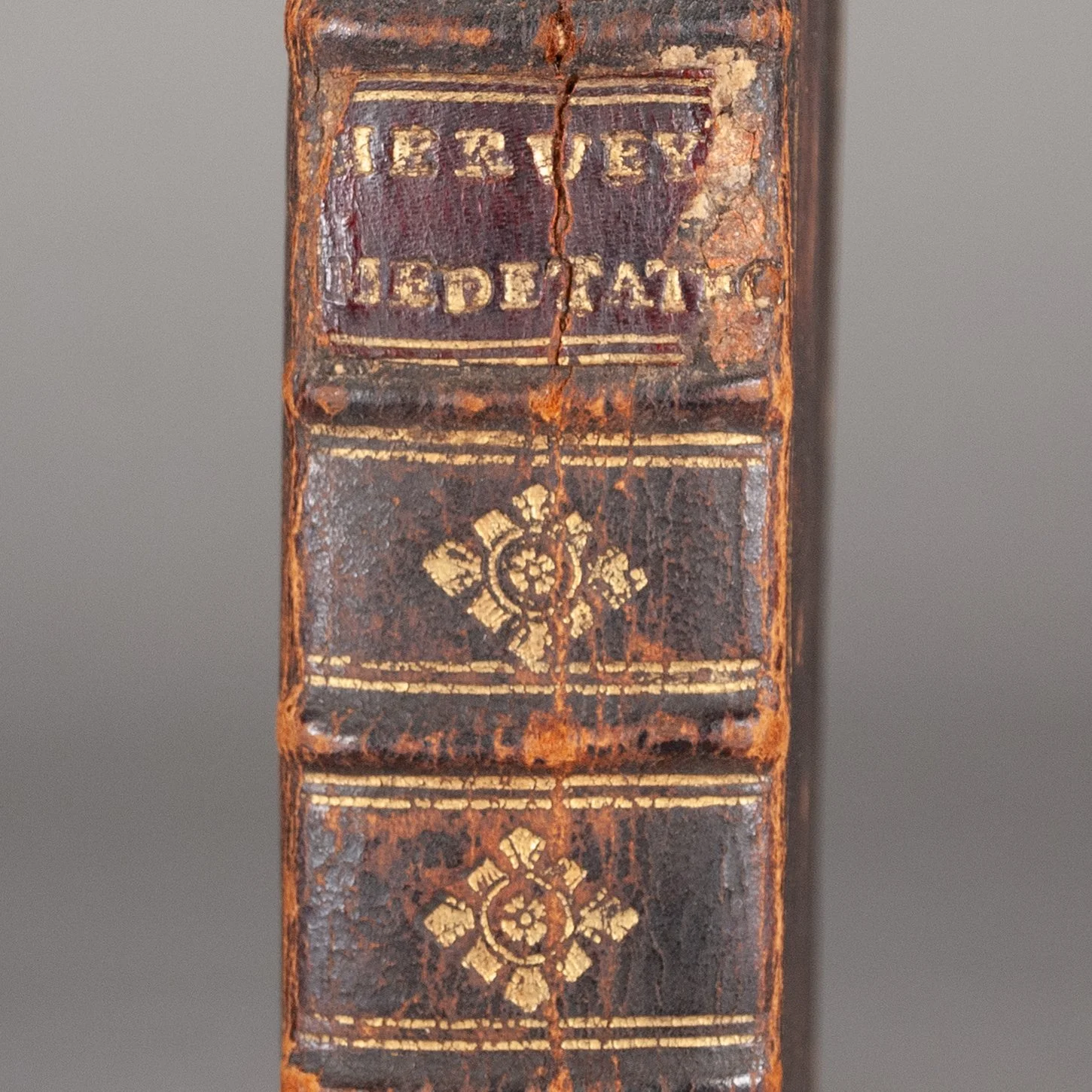

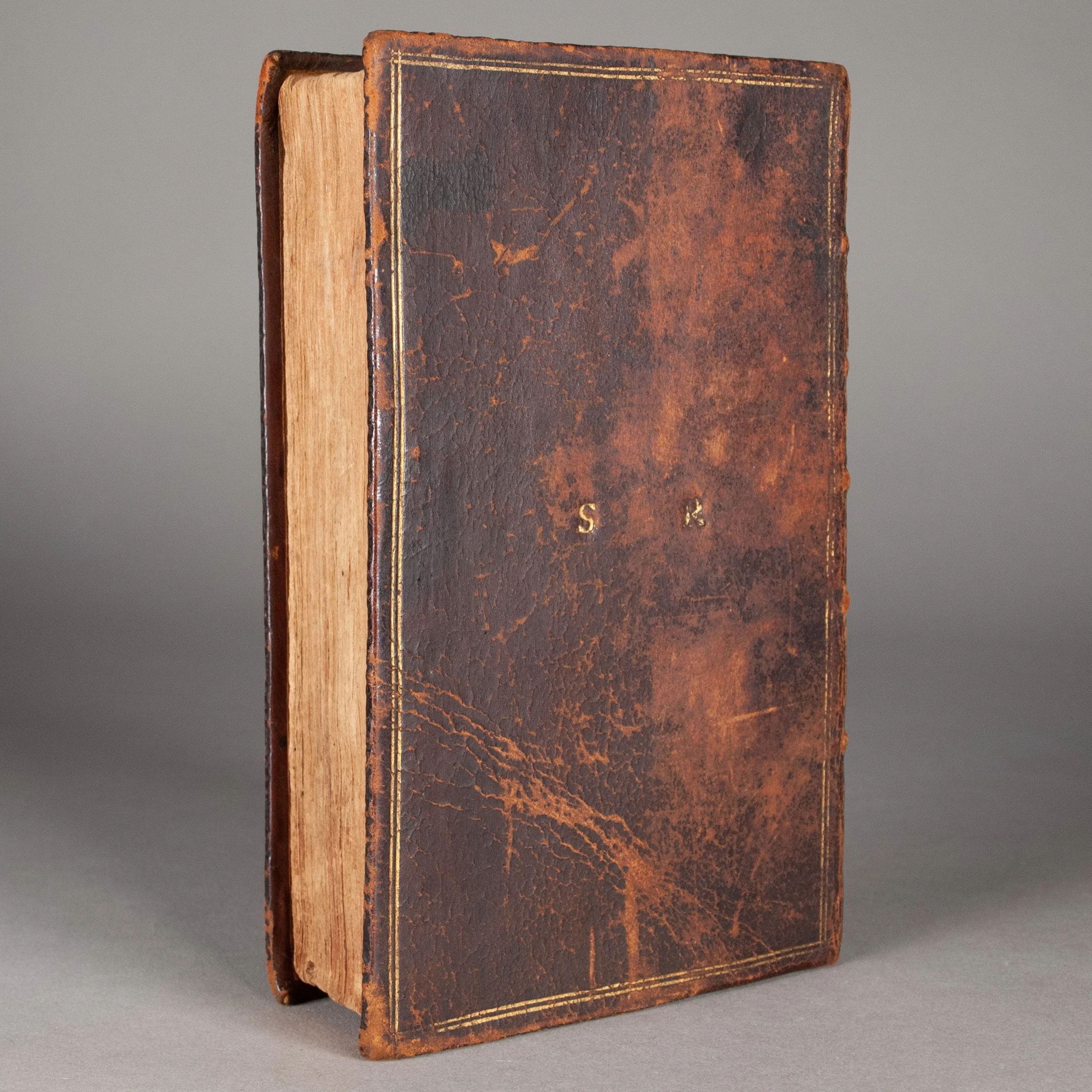

Likely the second American edition of the English clergyman's popular devotional. Smaller versions were published at London in 1746 and 1747, it reached its current expanded scope by 1748, and was frequently reprinted through the end of the century. The first American editions appeared at Philadelphia and Boston in 1750. We find stated fifth and sixth editions at London in 1749, and the Philadelphia edition is a stated seventh, so we suspect our stated eighth edition refers to its place in the greater chronology, rather than its strictly American position. ¶ Hervey belonged to the Evangelical Revival—known on this side of the Atlantic as the First Great Awakening—a movement that championed intense pious devotion, and one that notably cut across denominational divisions in the Protestant world. While he lacked the stature of John Wesley or Jonathan Edwards, Hervey did carve out for himself "an extraordinarily successful literary career" (ODNB). Beyond simply preaching this reformed theology, Hervey sought especially to bring the upper classes into the evangelical fold. His success might in part be attributed to his "peculiar ecstatic style," which blended his theology with the liveliness and popularity of Addison and Steele's Spectator. His approach was not for everyone then, nor for everyone now. Mary Wollstonecraft, for example, thought his Meditations and Contemplations "equally sinned against sense and taste." That said: "Modern distaste should not deprive him of his role as one of the most widely read writers of the evangelical revival" (ODNB). ¶ In an exceptionally early—and fortuitously dateable—colonial binding with spine in full gilt, certainly among the earliest recorded, and perhaps reasonably the earliest obtainable example. "Although a few gold-tooled bindings appeared in seventeenth-century Boston and elsewhere in America until the mid-eighteenth century, tooled decoration was almost always produced in blind" (Spawn). Simple gold fillets had been sporadically used over the decades, typically to panel or more simply frame the covers, and sometimes along the raised bands. On rare occasions, more elaborate rolls might be used in the same positions, or fleurons added to panel corners, surpassing the simple fillet. Gilt spine lettering is thought to have been introduced with a 1726 Boston imprint. ¶ But not until 1737 does Hannah French begin her history of "fully gilt backs," when spine compartments began receiving the gold treatment, touching off an attention to spine decoration that has yet to fade. "Books (other than psalm books) with fully gilt backs turned out before 1750 are sufficiently few to have special mention," she writes, citing just three Boston examples (1739, 1743, and 1749), and two from Philadelphia (1744 and 1748); we should also add a few impressive examples from the Mid Atlantic. While fully gilt spines were perhaps not quite hen's teeth in the years leading up to mid-century, decoration then still focused on the covers. The transition to spine-forward decoration didn't take off until the 1760s, placing our example firmly on the vanguard of full-gilt spines in the English colonies. At the same time, our binding retains a sympathetic link with the earliest use of gold on colonial American bindings: Sarah Ruggles's initials, stamped in gold on both covers, evoke the initials FB on a 1651 Bay Psalm Book, thought to be the first use of gold on an American binding. ¶ We searched more than a dozen likely phrases and found just one possibly comparable binding in auction records: a 1736 Chronological History of New England, "original full calf, gilt tooled," sold in 1944. American gilt work of this vintage is scarce in the trade to begin with, far more so with a spine in full gilt, and more still with an inscription that can so reliably date the binding.

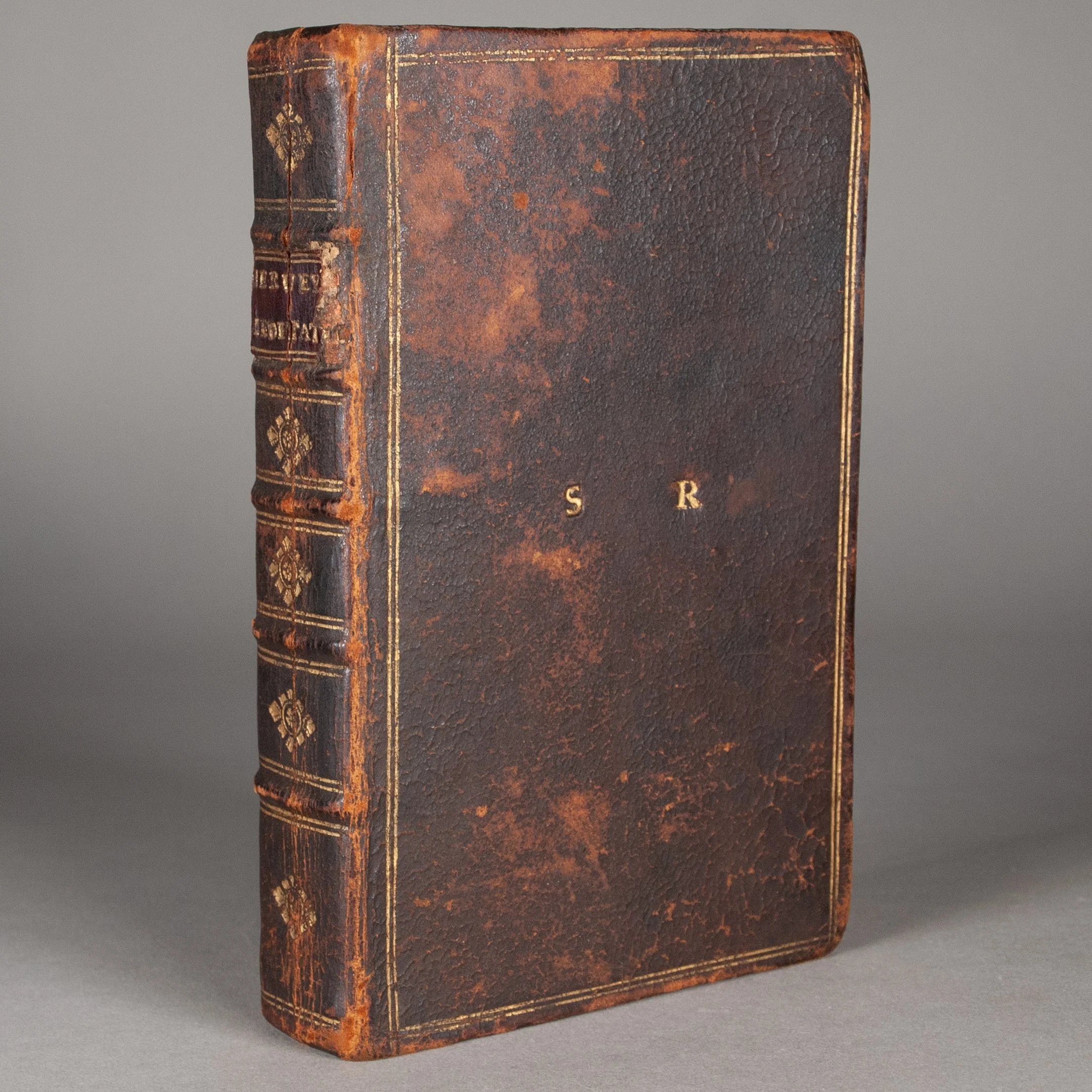

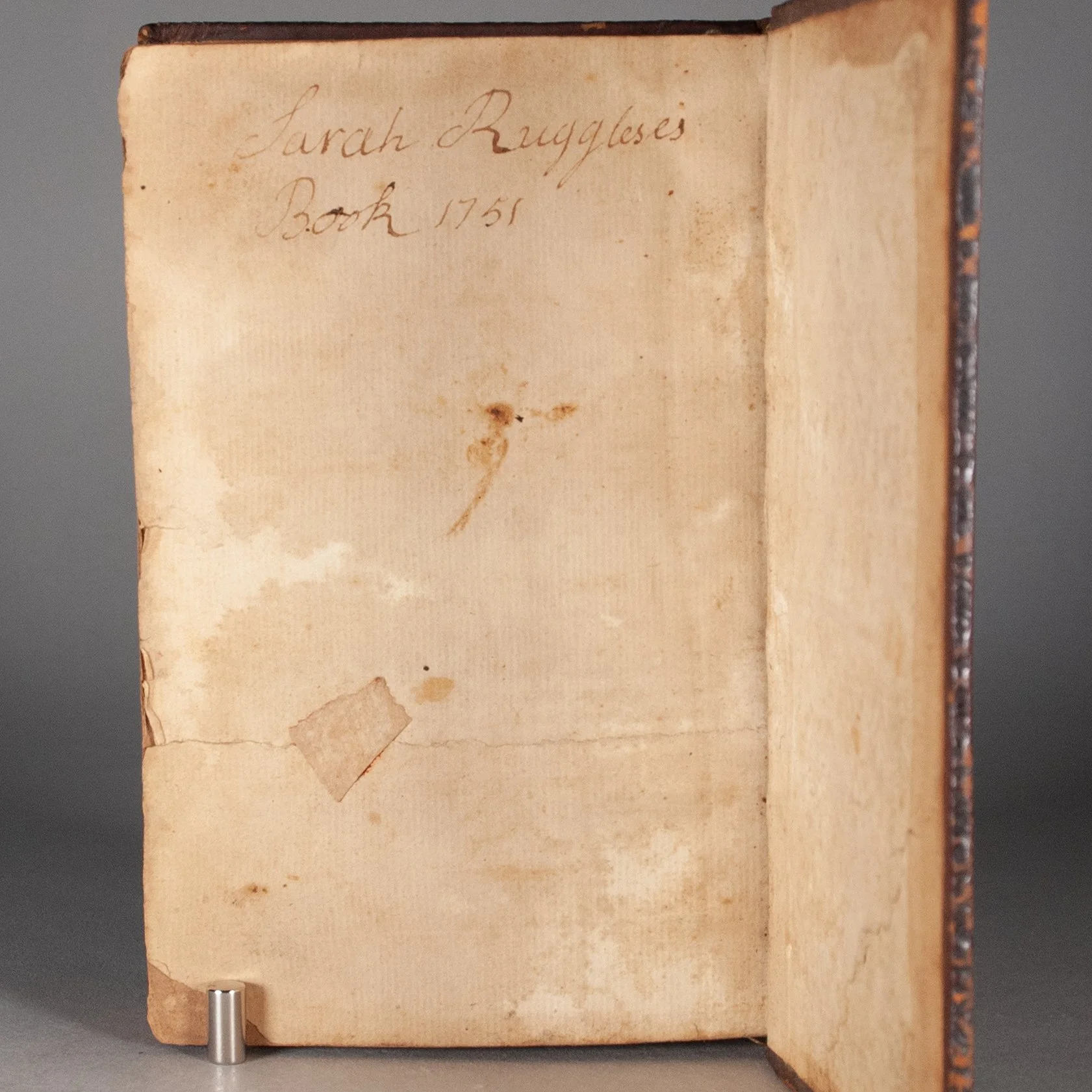

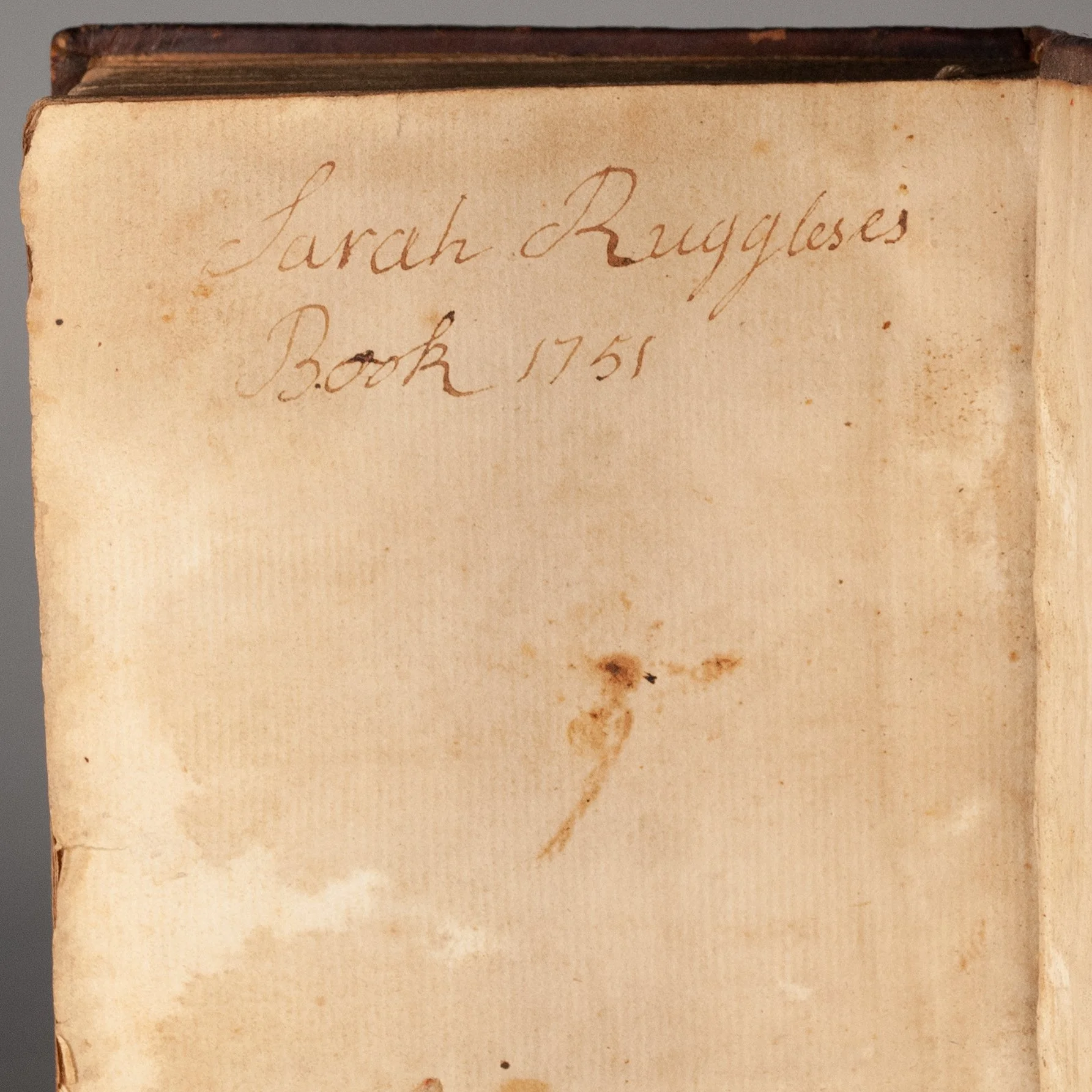

PROVENANCE: Initials SR gilt-stamped on each cover, and with a contemporary ownership inscription on the rear fly-leaf: Sarah Ruggleses Book 1751. This must be the same Sarah Ruggles (1732-1802) of Roxbury, Mass., who married Peter Parker ca. 1752/1753. She belonged to an old Boston family—her ancestor Thomas Ruggles arrived from England in 1637—whose land occupied most of what is today Boston's Mission Hill neighborhood. Given the general paucity of early colonial bindings with full-gilt spines, this must rank among the very earliest examples from a woman's library.

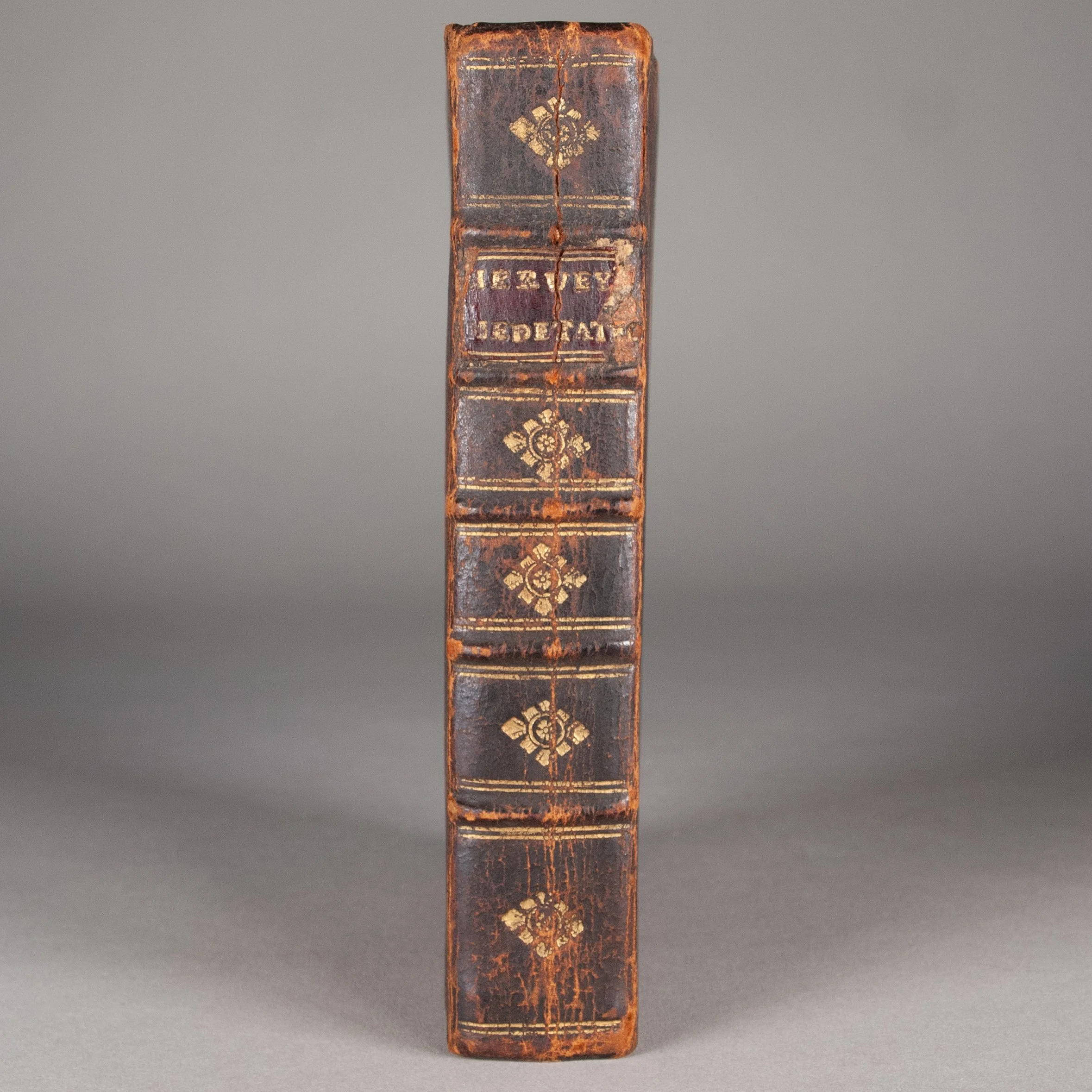

CONDITION: Contemporary brown leather, the spine in full gilt, with double fillets along each raised cord, each compartment with a small round flower within a larger decorative lozenge; leather spine label lettered in gold; covers with a double-fillet border in gold, plus the initials SR gilt-stamped in the middle of each board; board edges rolled in blind. We've been unable to match our spine tool to any known binder, and experts assure us that attempting such identification would be a fool's errand. For those curious, Hannah French ("Bookbinding in the Colonial Period") mentions a number of Boston binders active at the time, likewise an appendix to the catalogue of the 1907 Grolier Club exhibition of pre-1850 American bindings. ¶ The title quite tattered, with substantial loss, and a large tear repaired with old paper tackets; 3" tear in A4, affecting text; first and last few leaves a little dusty, and light foxing throughout; single wormhole in the lower corner of the text block, not affecting text; some negligible marginal dampstaining. Old crease across the lower corner of the rear board; leather generally scuffed and rubbed, and getting a bit dry (though nothing like redrot); leather cracked down the middle of the upper two spine compartments, but cords and joint leather are fully intact; tear across the rear fly-leaf, repaired with an old paper tacket. Frankly we're a little astonished at the condition.

REFERENCES: ESTC W30109 ¶ On the content: "Hervey, James," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004; "During this period [early 1740s] he firmly committed himself to the doctrines of free grace and justification by faith that he was to teach for the rest of his life...As a writer Hervey had two main aims: to propagate the Reformation theology that he believed, like other members of the evangelical movement, had been abandoned by the Church of England, and to draw on the intellectual and aesthetic interests of the wealthy and polite in order to draw them to Christ...[His style], which delighted huge numbers of readers and disgusted some critics, was the result of his attempt to combine the language of puritan meditation with that of The Spectator and Shaftesbury's Moralists (though he never mentioned the latter). His ideal was what he called Christ's style."); Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Chapter V, Section II ¶ On the binding: Willman Spawn, "The Evolution of American Binding Styles in the Eighteenth Century," Bookbinding in America 1680-1910 from the Collection of Frederick E. Maser (1983), p. 29 ("Of the leather-bound books that have come down to us from the early 1700s, most are in very plain bindings of sheepskin, tooled on the boards in a panel design, but with the spines left bare. This simplicity is not a testimony to lack of skill on the part of the binder, but rather to the popularity of that style."), 30 (cited above), 32 (citing Hannah French's 1737 discovery), 35 ("for the first fifty to sixty years of the eighteenth century, the basic binding style in use in the American Colonies emphasized decorated boards, with little or no decoration on the spine. The 1760s would be the transitional years to a reversal in emphasis, to fancy spines and plain boards for all books except the extra-gilt category, in which the boards continued to be tooled."), 36 ("The emphasis on the spine that had begun before the Revolution continued in the postwar years"); Hannah D. French, Bookbinding in Early America (1986), p. viii ("most of the seven hundred or more American binders at work between 1660 and 1820 are presently known only as names taken from directories and newspaper advertisements, which makes it next to impossible to identify examples of their work accurately"), 124 (cited above), 129-132 (cited above, a good summary of gilt used on colonial bindings), 136 ("By 1750, gilt bindings were coming into fashion in Boston, Philadelphia, and a few years later in New York"); Hannah French, "Bookbinding in the Colonial Period (1636-1783)," Bookbinding in America (1941), p. 21 (for the 1726 introduction of gilt lettering; "The use of gold was not widespread before the Revolution. When it was used, it was most often limited to a double gold fillet around the covers, and for a roll to border the cords on the back."), 32-33 (listing some Boston binders of the time); Catalogue of Ornamental Leather Bookbindings Executed in America Prior to 1850 (1907), p. 94-95 (list of Boston binders active at this time); C. Clement Samford and John M. Hemphill II, Bookbinding in Colonial Virginia (1966), frontispiece (gilt binding on a 1736 imprint), plate 5 (another on a 1736 imprint) ¶ On the provenance: John William Linzee, The History of Peter Parker and Sarah Ruggles of Roxbury, Mass. (1913), p. 148 (for the Parker-Ruggles marriage), 448 (on Thomas Ruggles)

Item #816