Lavish presentation manuscript by accomplished provincial scribe

Lavish presentation manuscript by accomplished provincial scribe

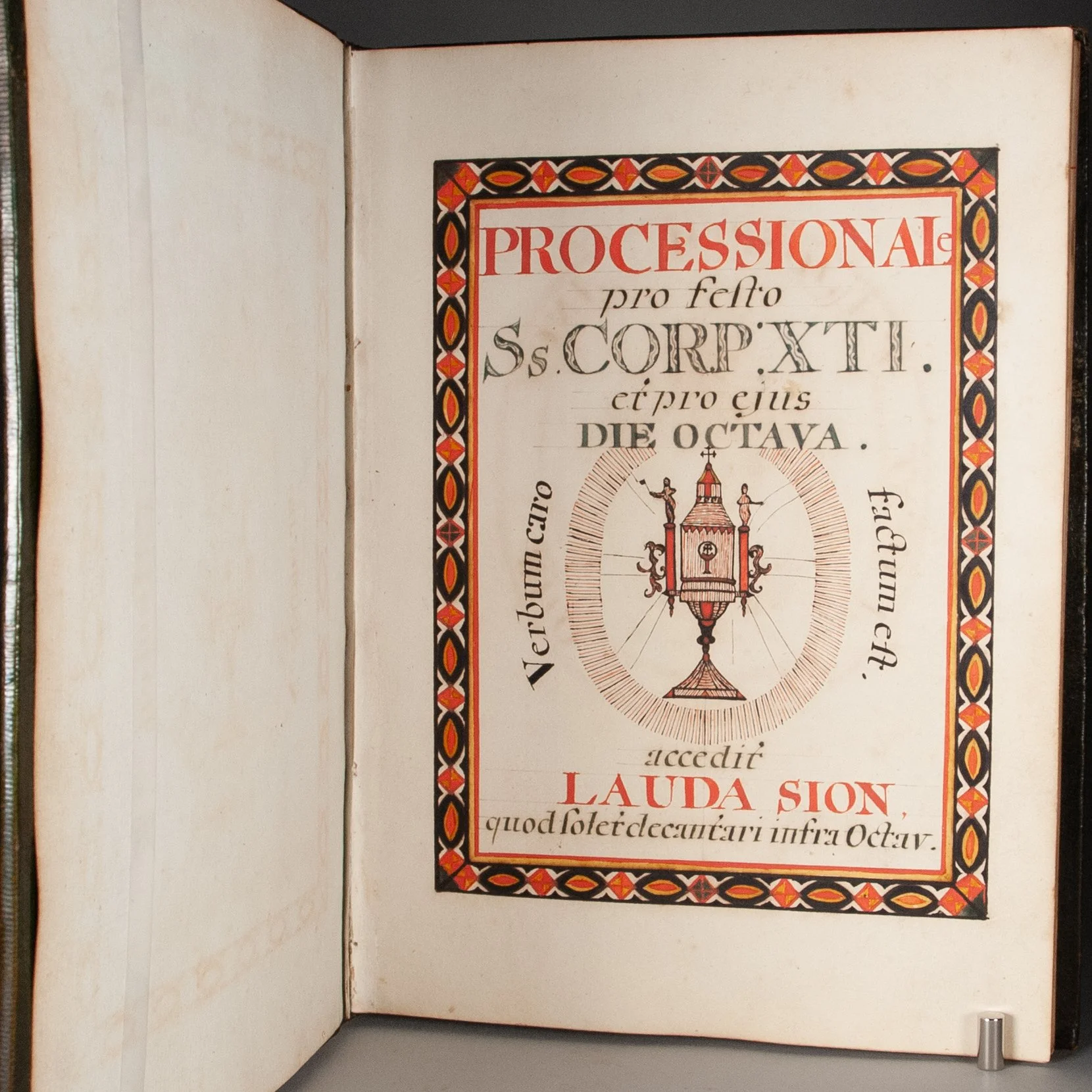

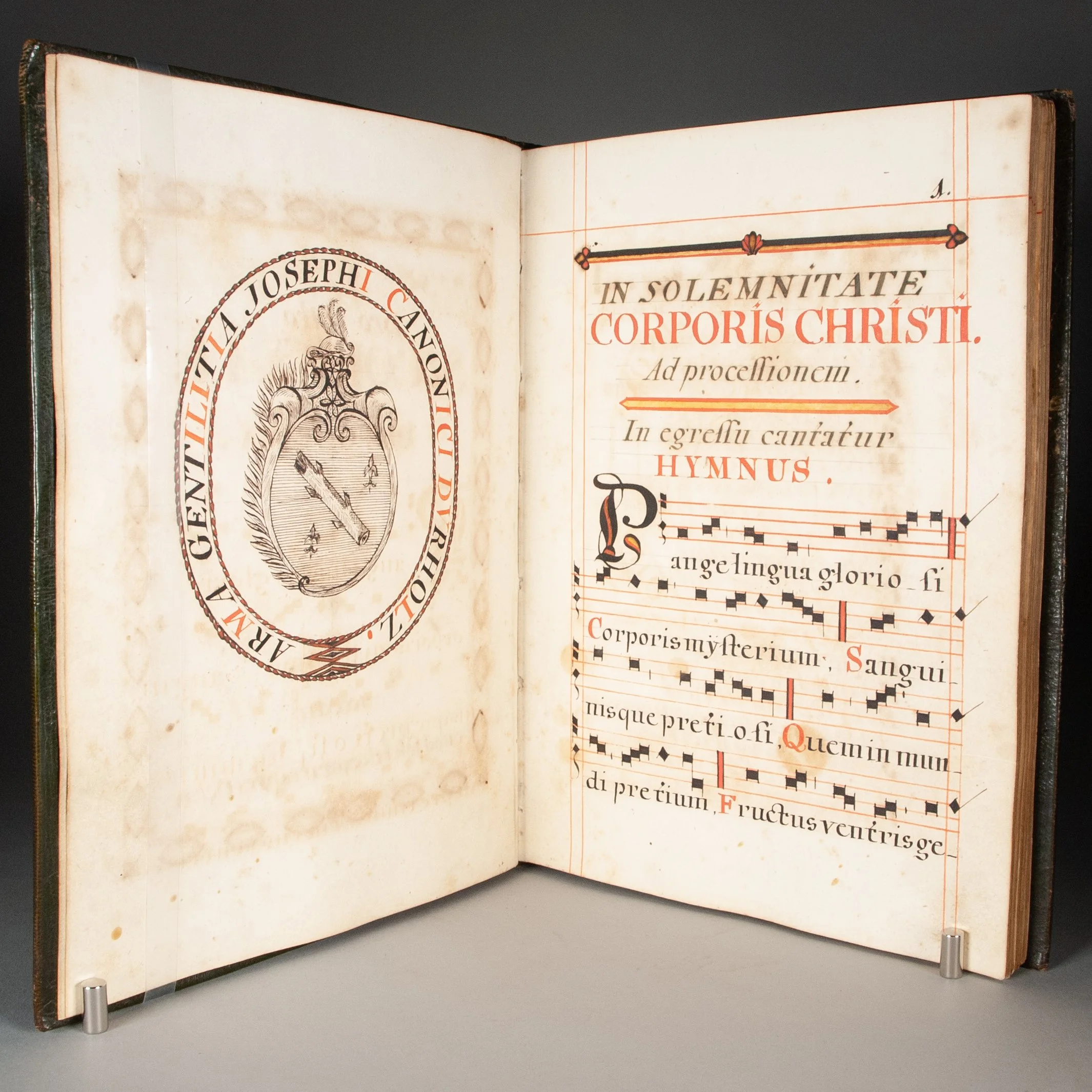

Processionale pro festo Ss. Corp. Xti. et pro ejus die octava; accedit Lauda Sion, quod soler decantari infra octav.

copied by Eusebius Ris

Solothurn, [between 1809 and ca. 1820 (1812 or 1816?)]

[2], 76, [2] p. | 4to | [A]-[H]^4 [I]^6 [K]^2 | 237 x 171 mm

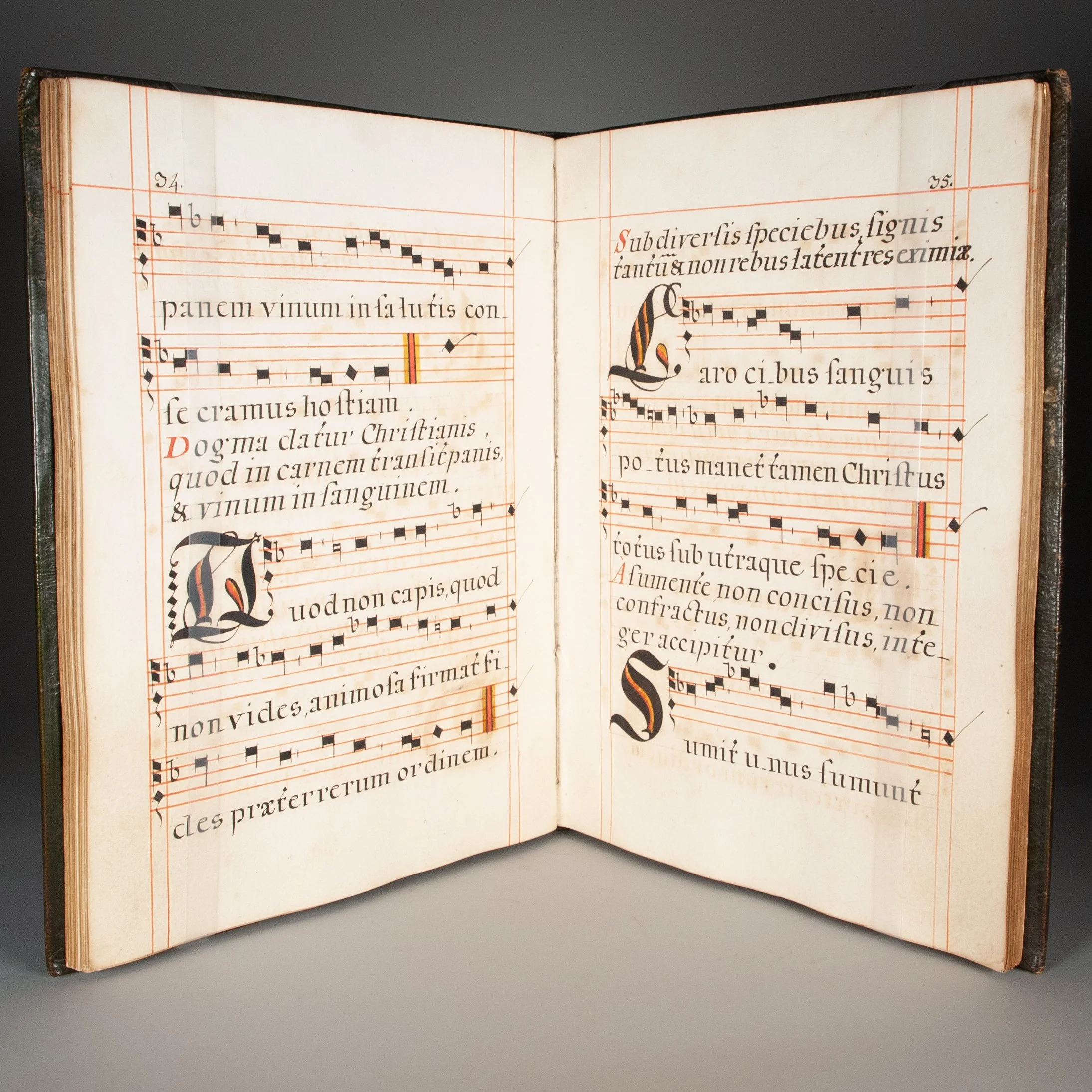

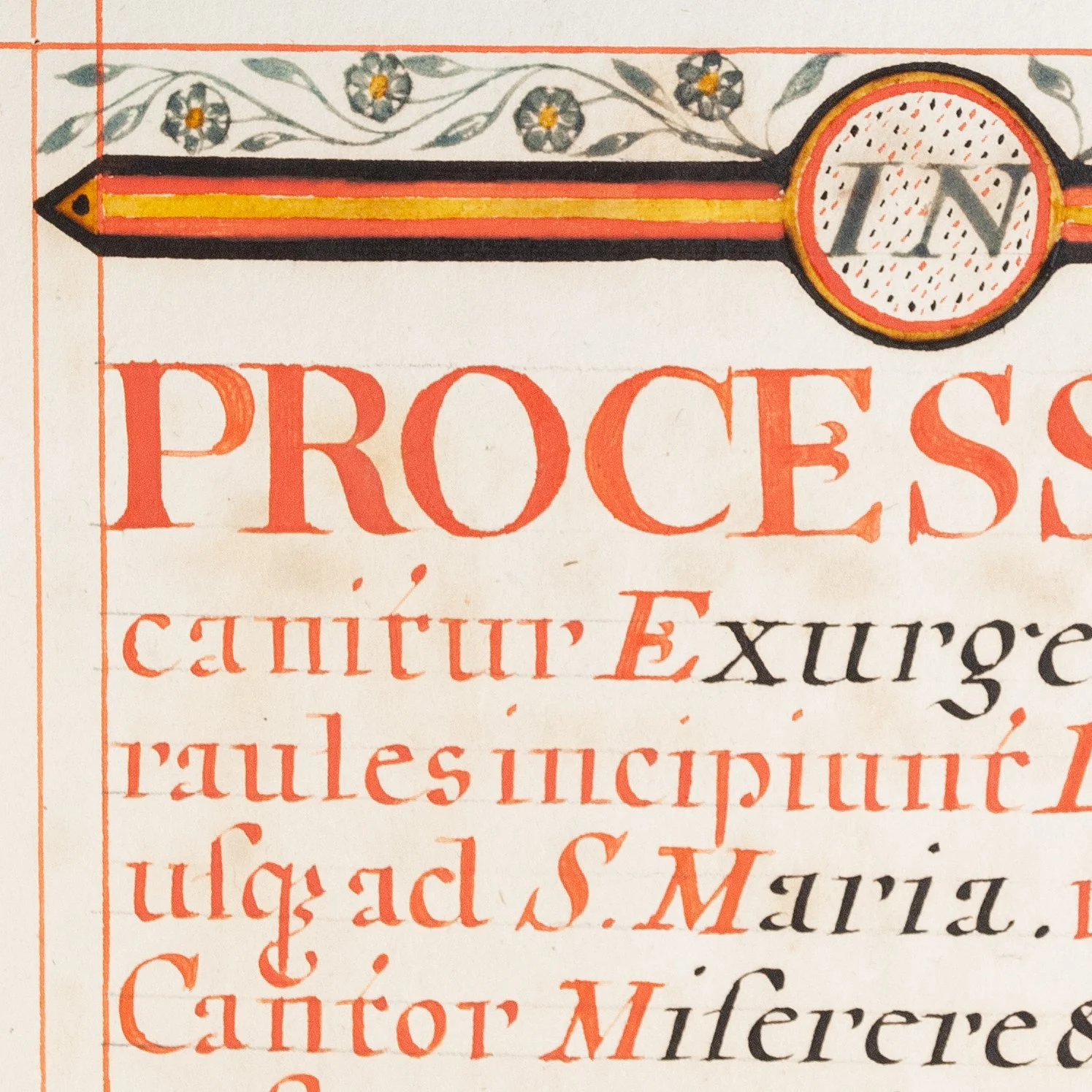

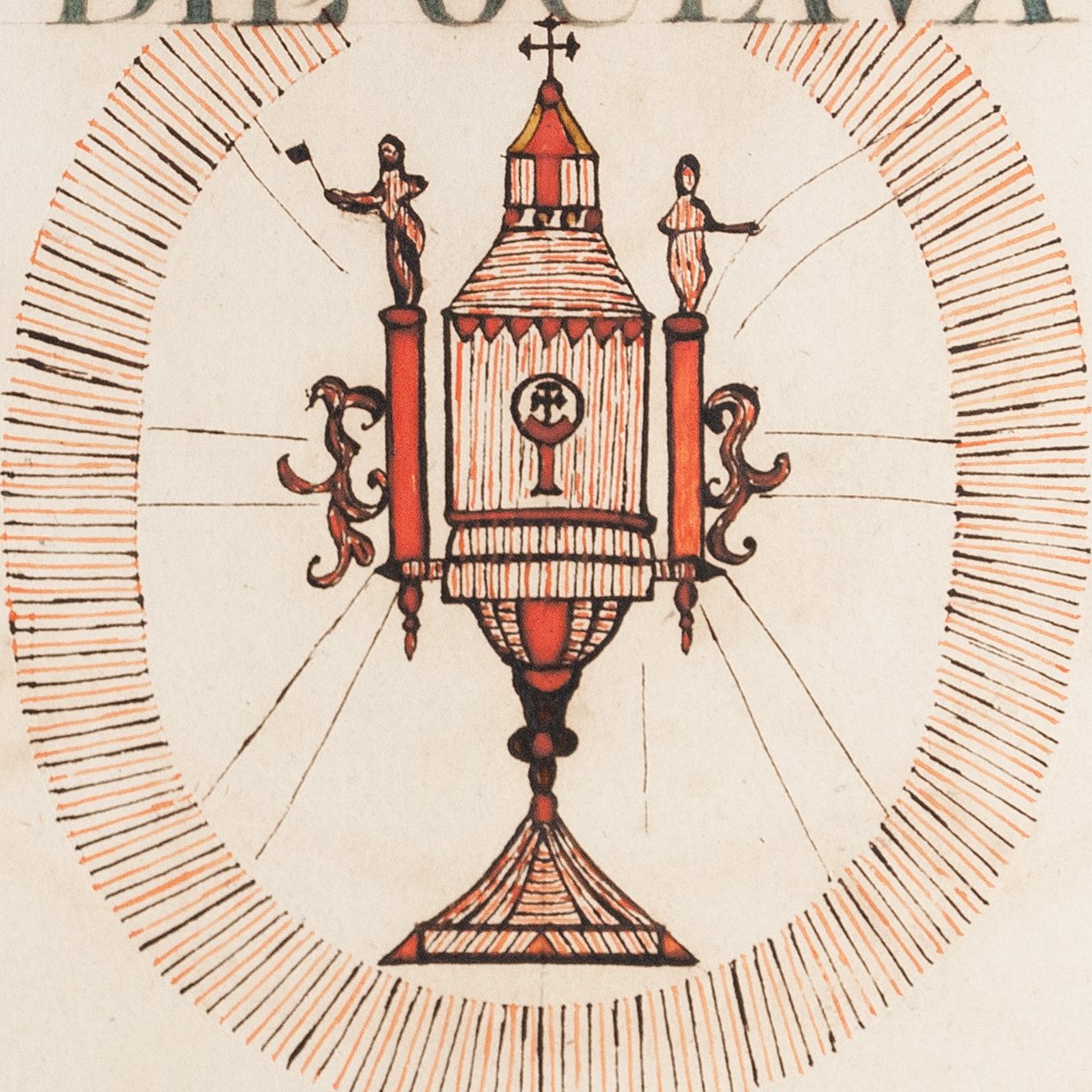

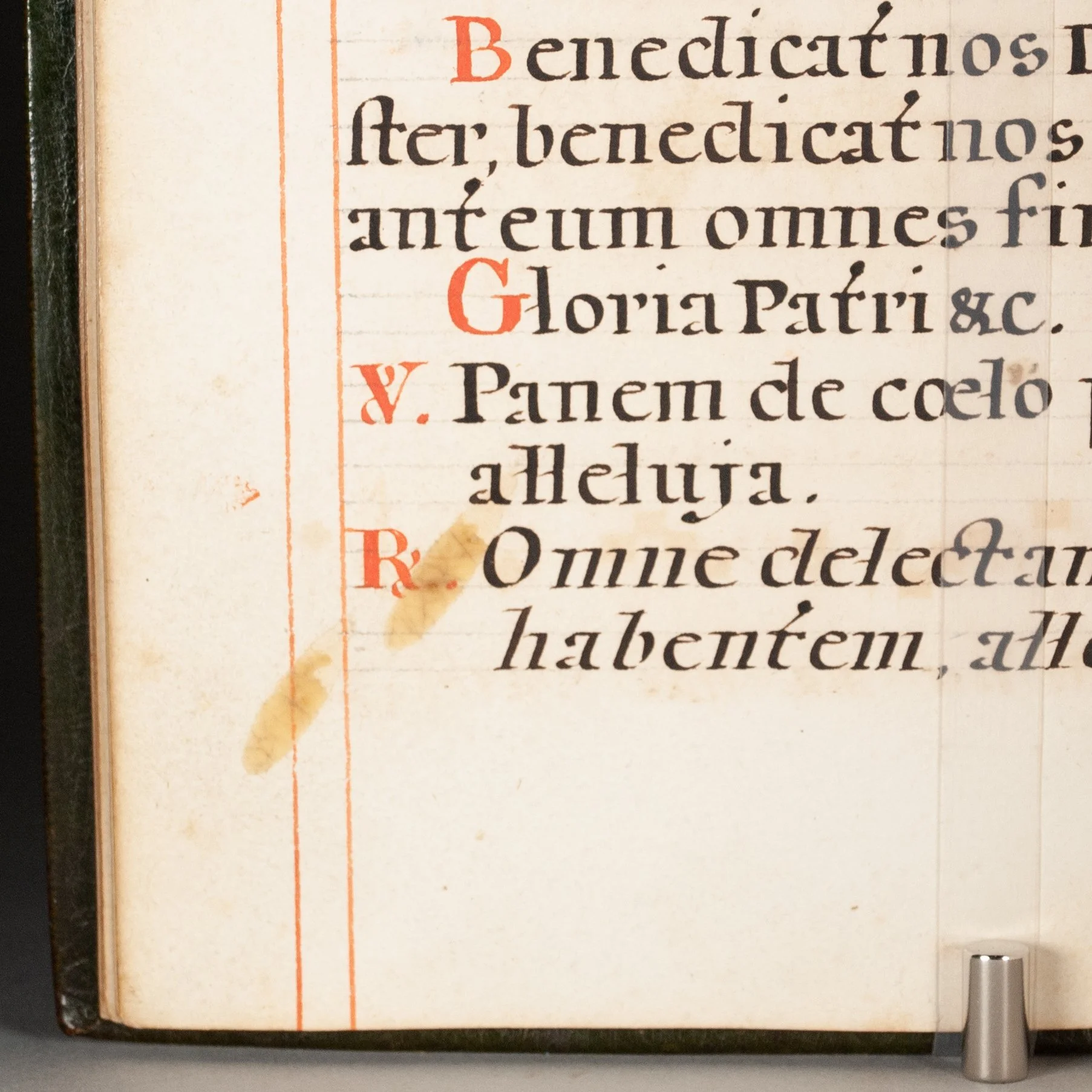

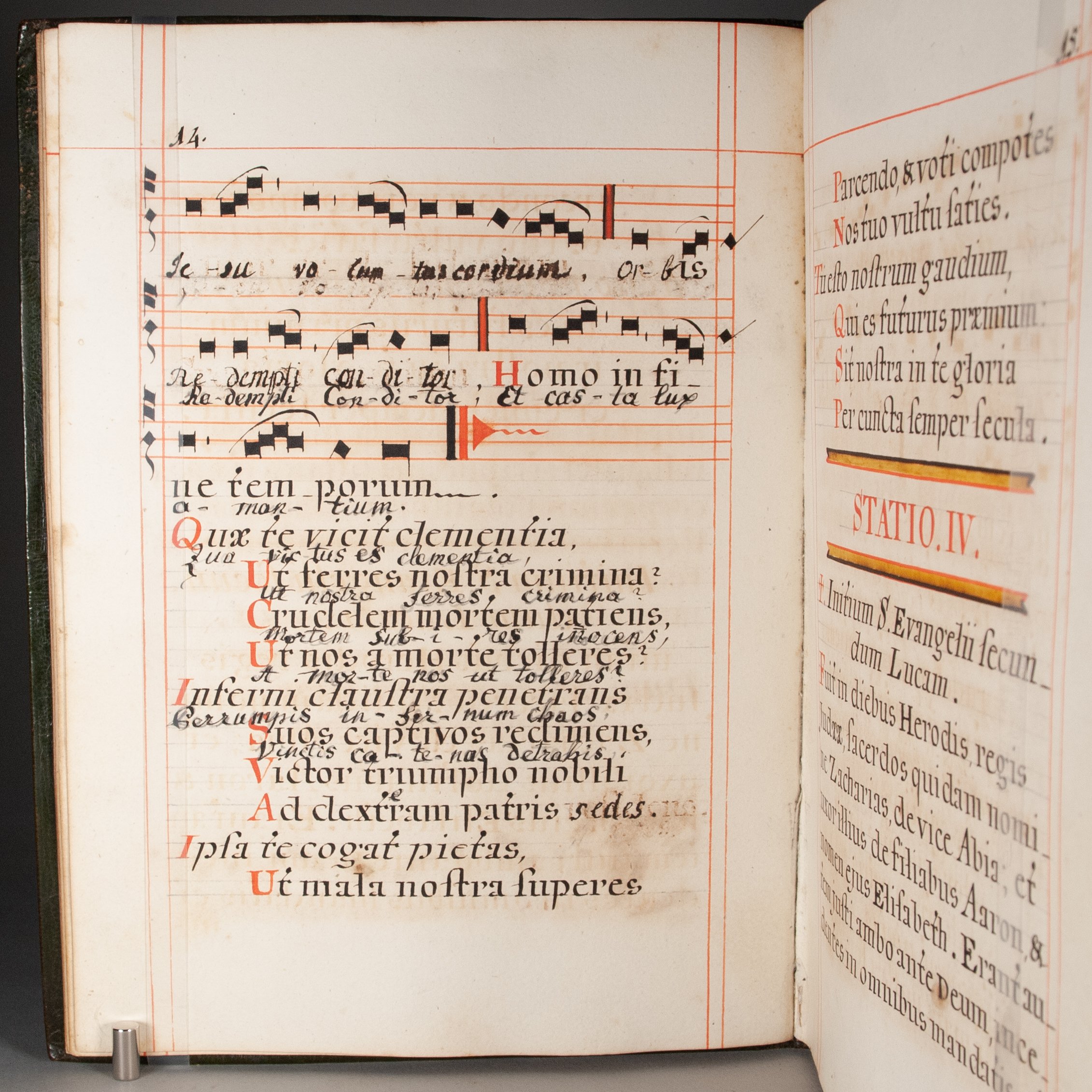

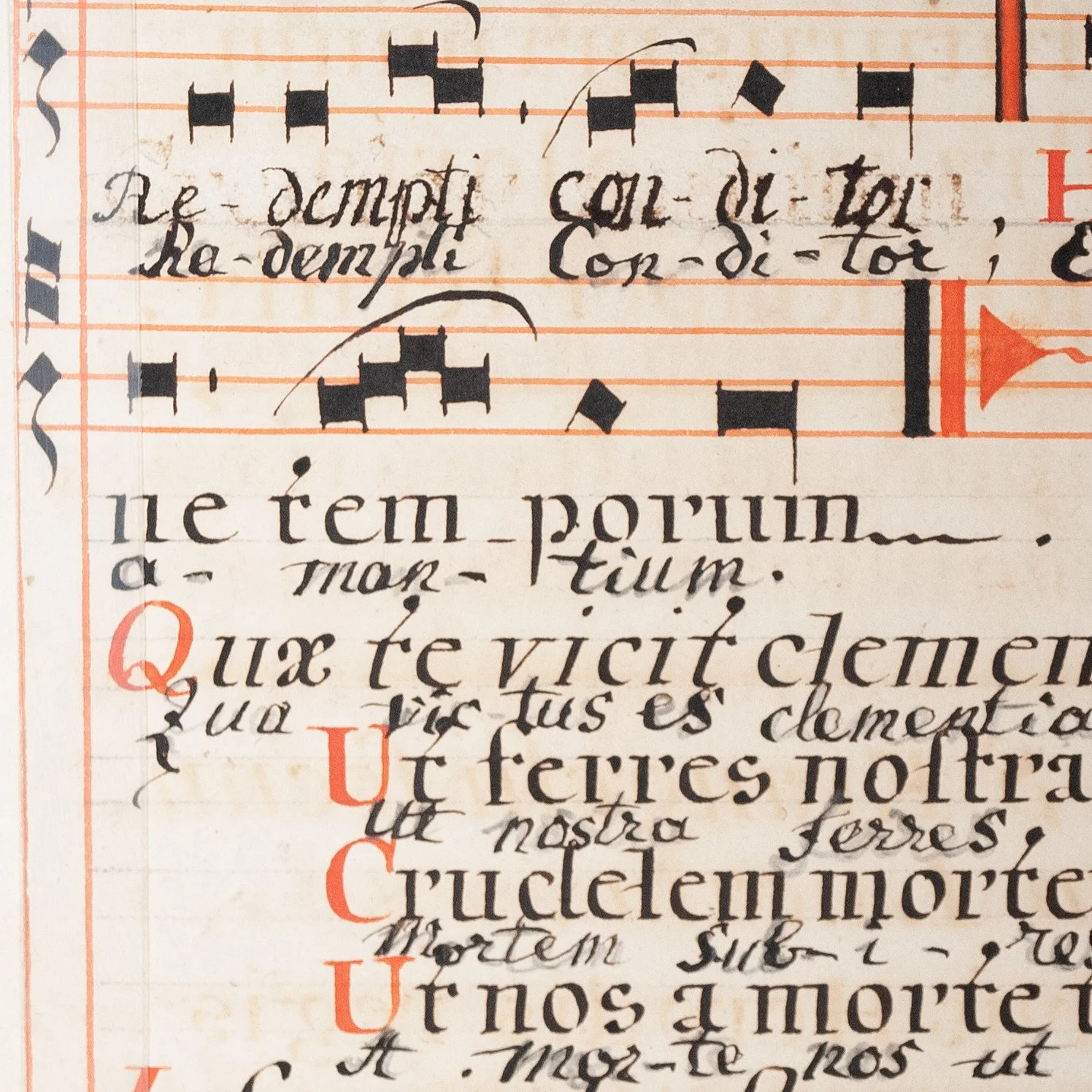

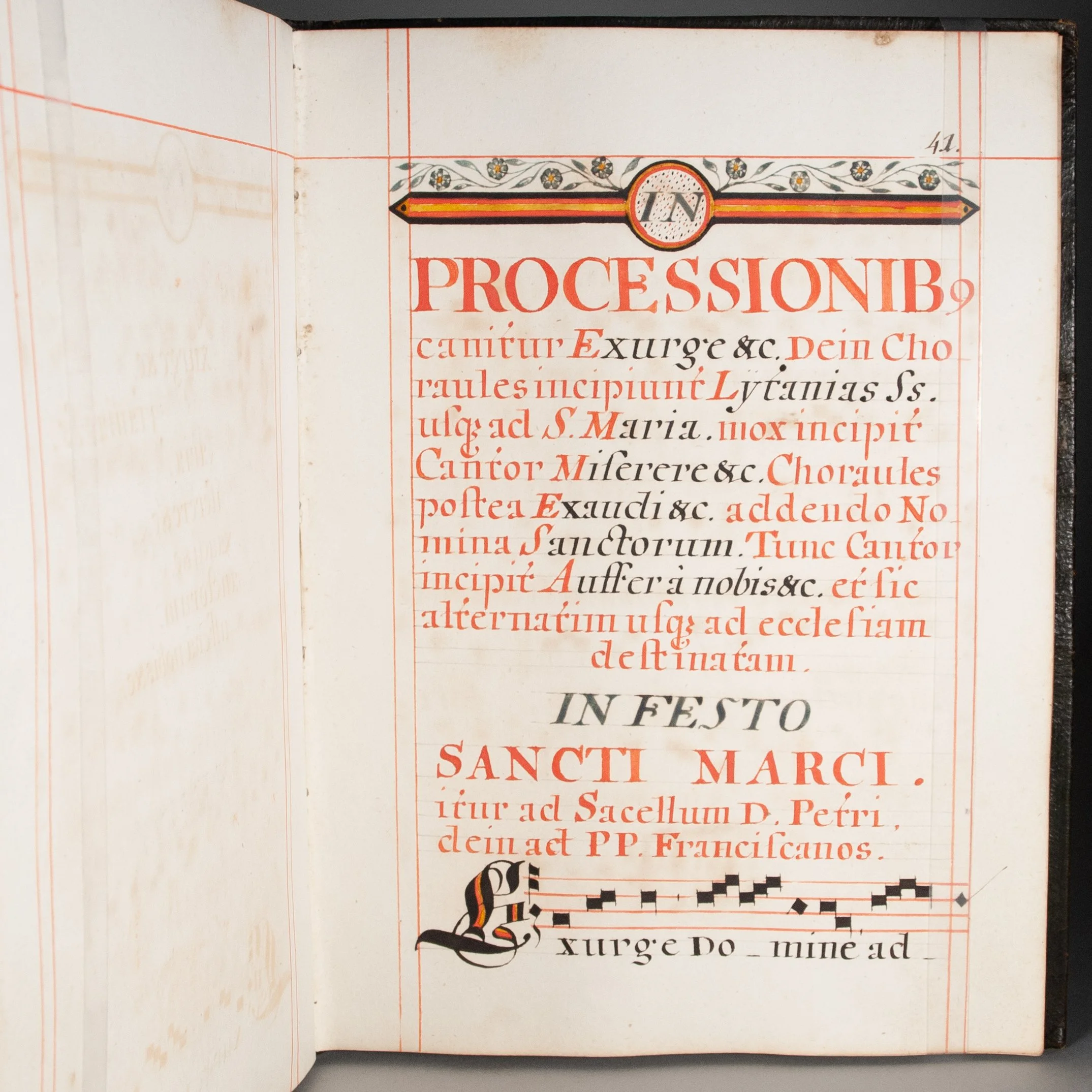

A lavish liturgical manuscript produced by an exceptional provincial scribe in Switzerland. The book's eponymous focus is the Feast of Corpus Christi, here accompanied by the Lauda Sion hymn sequence, but there's much more inside: text and music for the Feast of St. Mark, Rogation Days, Pentecost, and the Feast of St. Ulrich. Altogether, it's something of a liturgical vade mecum for Easter and Pentecost Seasons. ¶ Written in three colors on thick wove paper, the book partakes of both manuscript and print traditions. The pages are pricked to facilitate a square layout, then lightly ruled in lead, echoing a method that became popular in the 12th century. For its part, the mise-en-page of the title, with its vignette flanked by an epigram, reflects a composition established only in the age of print. Written in neat roman and italic scripts, the manuscript is rich in notated music, with black notes on red staves of both four and five lines. The text, too, is in black and red, with instructions to the priest in green, and musical notation invariably begins with multi-line decorative initials—occasionally solid red, but more frequently elaborate Fraktur initials in black, orange, and red. ¶ The manuscript is signed at end by one Eusebius Ris, native of Grenchen, a Swiss town north of Bern, who by 1787 was in nearby Solothurn as a Catholic priest and private tutor, then as chaplain in 1798. (Even the locus of production evokes the central role the church played in producing medieval manuscripts.) The Central Library in Solothurn holds a number of manuscripts that belonged to Ris, some of them (like ours) signed by Ris himself as scribe, altogether spanning some twenty or thirty years. Most of them are musical and decorative in nature, some even illustrated, and at least one other is a contemporary gilt-stamped green binding. All to say, our scribe spent years exercising a particular devotion to the art of the handwritten book. ¶ We're endlessly captivated by manucripts made during the age of print, as they remained an important method of textual distribution for a variety of reasons. While the Council of Trent did a great deal to standarize the Catholic Liturgy, there continued to be minor variations from diocese to diocese. Michel Péronnet, for example, found the early 18th century to be one of the great ages of such book production, "when diocesan books triumphed." Liturgical texts continued to evolve, too, forcing owners to either buy new copies or update existing ones (reflected here with some altered text). So there was frequently an economical argument for the handwritten liturgical book, notated music especially. To be sure, "a portion of the liturgical production of the 17th and 18th centuries remained in manuscript while the particular nature of their uses demanded an extremely limited distribution, sometimes to just a single ecclesiastical institution" (Sordet). No doubt this was a factor with the present manuscript, and others that Ris produced, though we suspect there was also a motivating desire to impress a church official with a sumptuous gift. Given the book's deluxe nature, and the arms of one Canon Joseph Durholz on the title verso, Ris presumably made this as a presentation manuscript for Urs Joseph Dürholz, who appears in Solothurn church records as preacher in 1809, elevated to official Stiftsprediger in 1812—presumably in what is today the St. Ursus Cathedral—then as canon in 1816. ¶ Ris signs his name at end with Sacellan[us], so he certainly must have made it after being named chaplain in 1798, and doubtless not until Dürholz arrived in 1809. If prepared for a special occasion in Dürholz's career, we might suggest his appointment as Stiftsprediger in 1812 or canon in 1816, when any liturgical text would have served him well. Wax drippings indicate the book was certainly used. It's worth noting that at least two other Ris productions in the Solothurn library belonged to local canons. This early 19th-century dating would be consistent with the thick, handmade wove paper—note scattered vatman's tears and variations in texture—positioning it before the widespread adoption of machine-made wove paper. This is also consistent with the contemporary binding's use of laid paper for endleaves. ¶ An absorbing book that combines both scribal and print conventions, and the work of someone who clearly cultivated the scribal art deep into the age of print—and someone who obviously believed the manuscript could still offer something beyond the reach of the common press.

PROVENANCE: A hymn on p. 13-14 was later updated: the words of notated music have been obliterated and rewritten, with additional interlinear additions below. ¶ Arms of Joseph Dürholz on the title verso, clearly added by Ris as part of the book's original production. Ownership signature of John Galvin, Dublin, on the front fly-leaf, and a descriptive note by him loosely laid in. We purchased from a New York auction house, to them from the estate of a longtime collector.

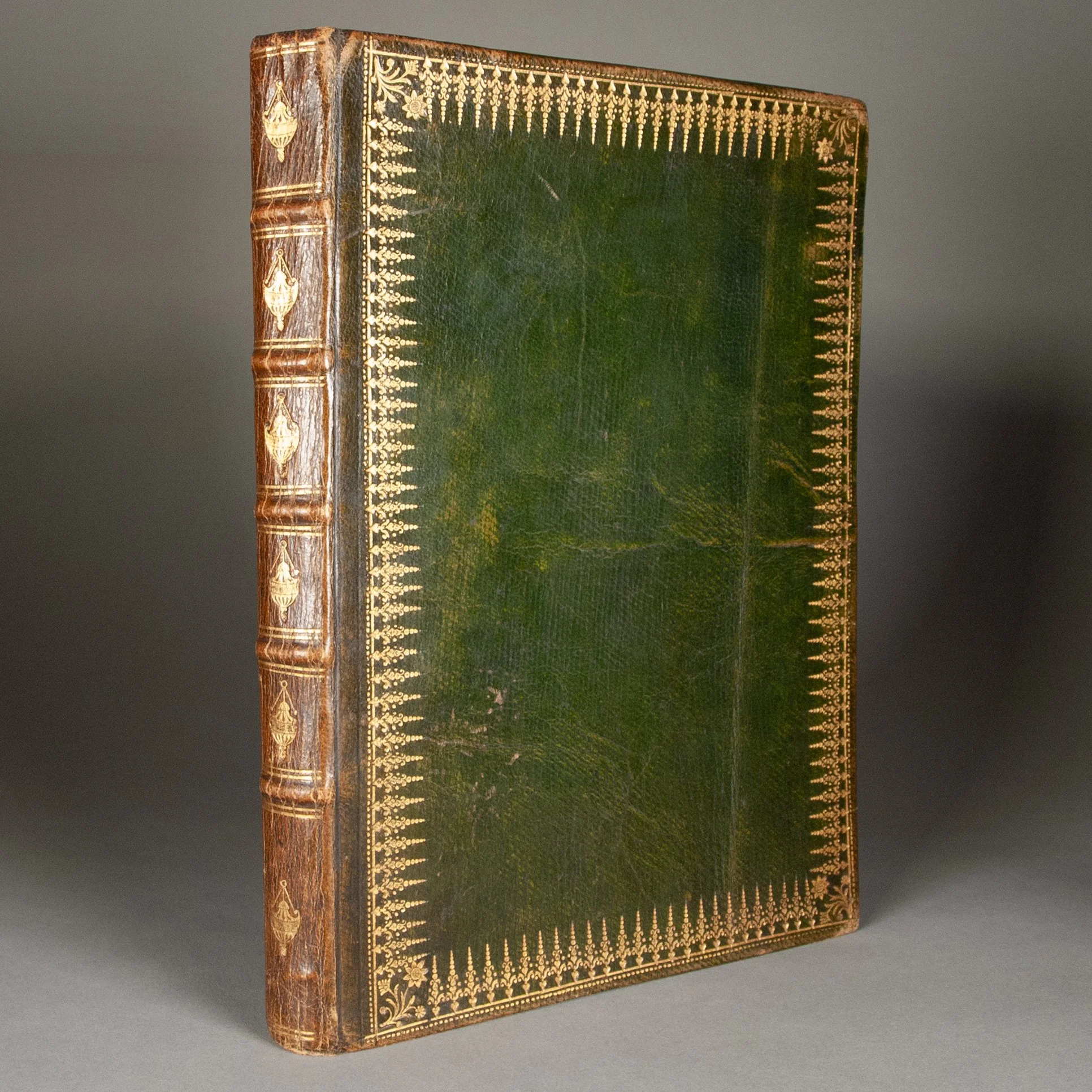

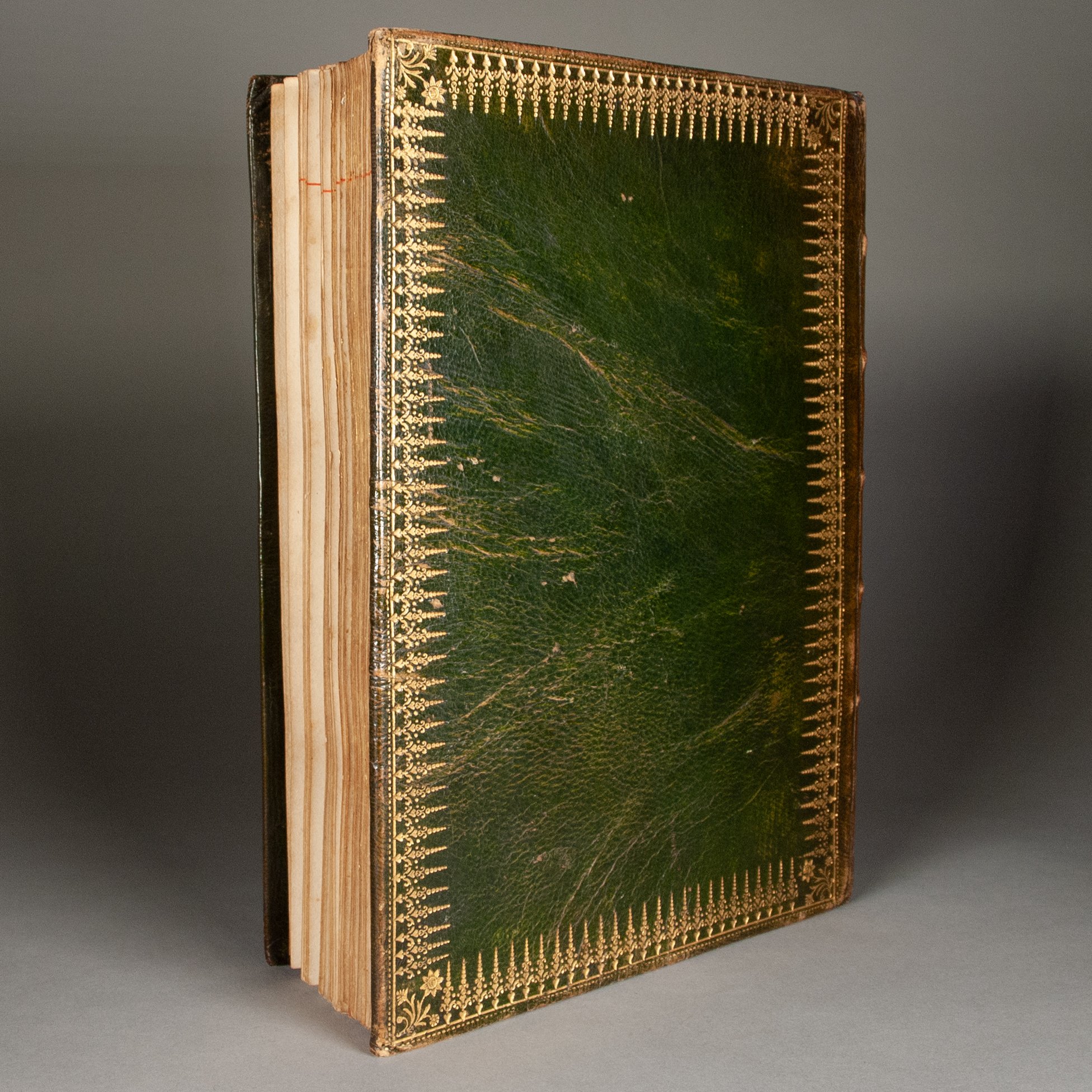

CONDITION: Contemporary green leather, spine and board edges tooled in gold; all edges gilt. Given a similar binding on at least one of Ris's manuscripts at Solothurn, we suspect the scribe himself coordinated the binding. Handwritten on thick handmade wove paper, as described above. Last leaf of our collation is blank save for a ruled frame in red, but eight additional (completely) blank leaves follow, the same stock as Ris's work. ¶ Scattered foxing, and the margins of some leaves rather finger soiled; a few scattered drops of wax. Binding lightly worn at the extremities, but really a nice book inside and out.

REFERENCES: Alexander Schmid, Die Kirchensätze, die Stifts- und Pfarr-Geistlichkeit des Kantons Solothurn (1857), p. 21 and 24 (Dürholz in Solothurn), 67 (Dürholz in Schönenwerd), 239 (variety of dates for Dürholz), 282 (for Ris's few biographical details); Christopher de Hamel, Making Medieval Manuscripts (2018), p. 56 (on manuscript ruling in the later Middle Ages); Michel Pérronet, "Les évêques français et le livre au XVIe siècle: auteurs, éditeurs et censeurs," Le livre dans l'Europe de la Renaissance (1988), p. 162 (cited above); Yann Sordet, Histoire du livre et de l'édition (2021), p. 445 ("manuscript distribution remained an important method of textual distribution until the end of the 18th century. Various reasons explain this choice for certain work or for certain corpora: economic constraints, a wish to control circulation of the text, imperatives of prudence and discretion."), 447 (cited above)

Item #927