Seamstress's advice

Seamstress's advice

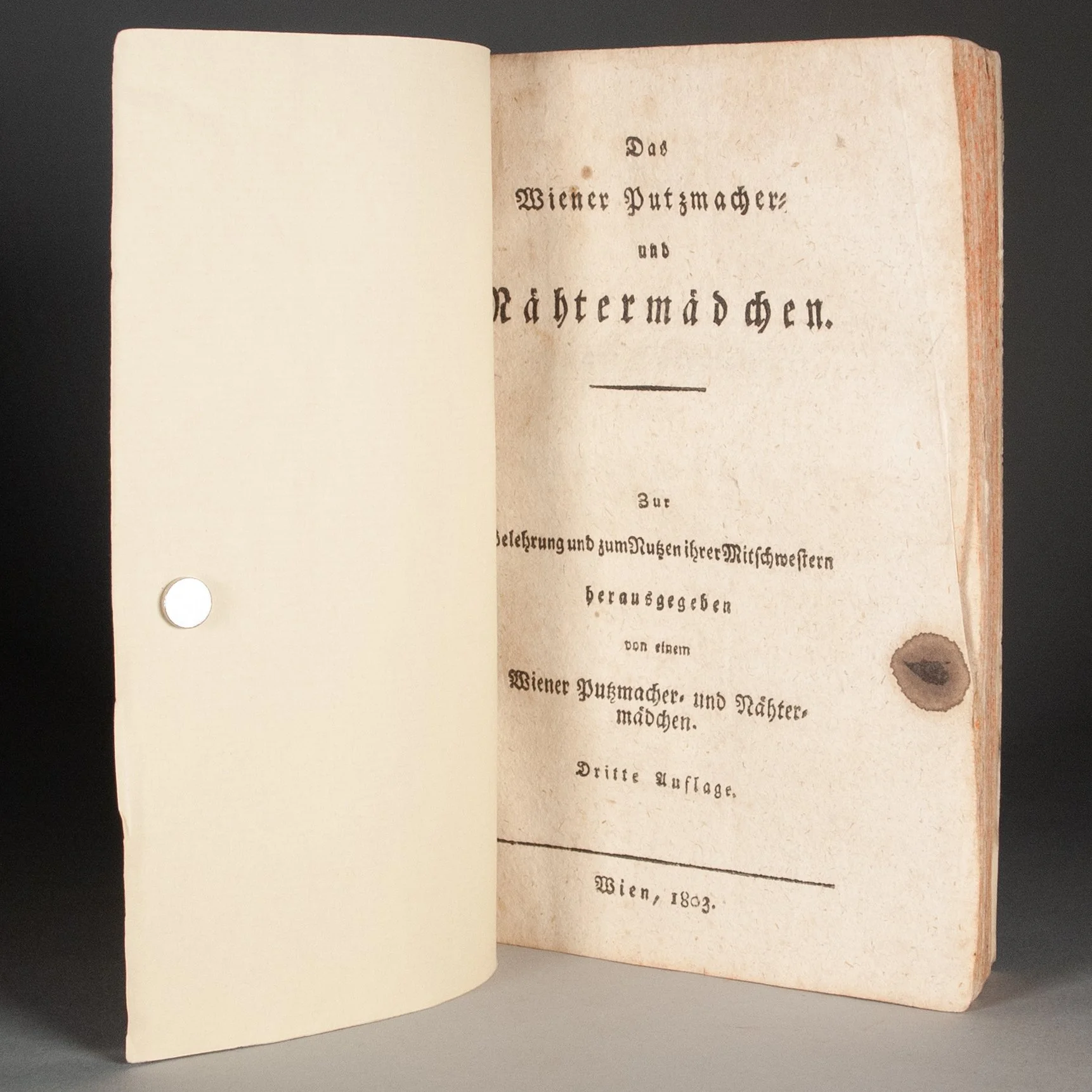

Das Wiener Putzmacher- und Nähtermädchen; zur Belehrung und zum Nutzen ihrer Mitschwestern, herausgegeben von einem Wiener Putzmacher- und Nähtermädchen; dritte Auflage

Vienna, 1803

[8], 174, [2] p. | 8vo | *^4 A-K^8 L^4 M^4 | 161 x 105 mm

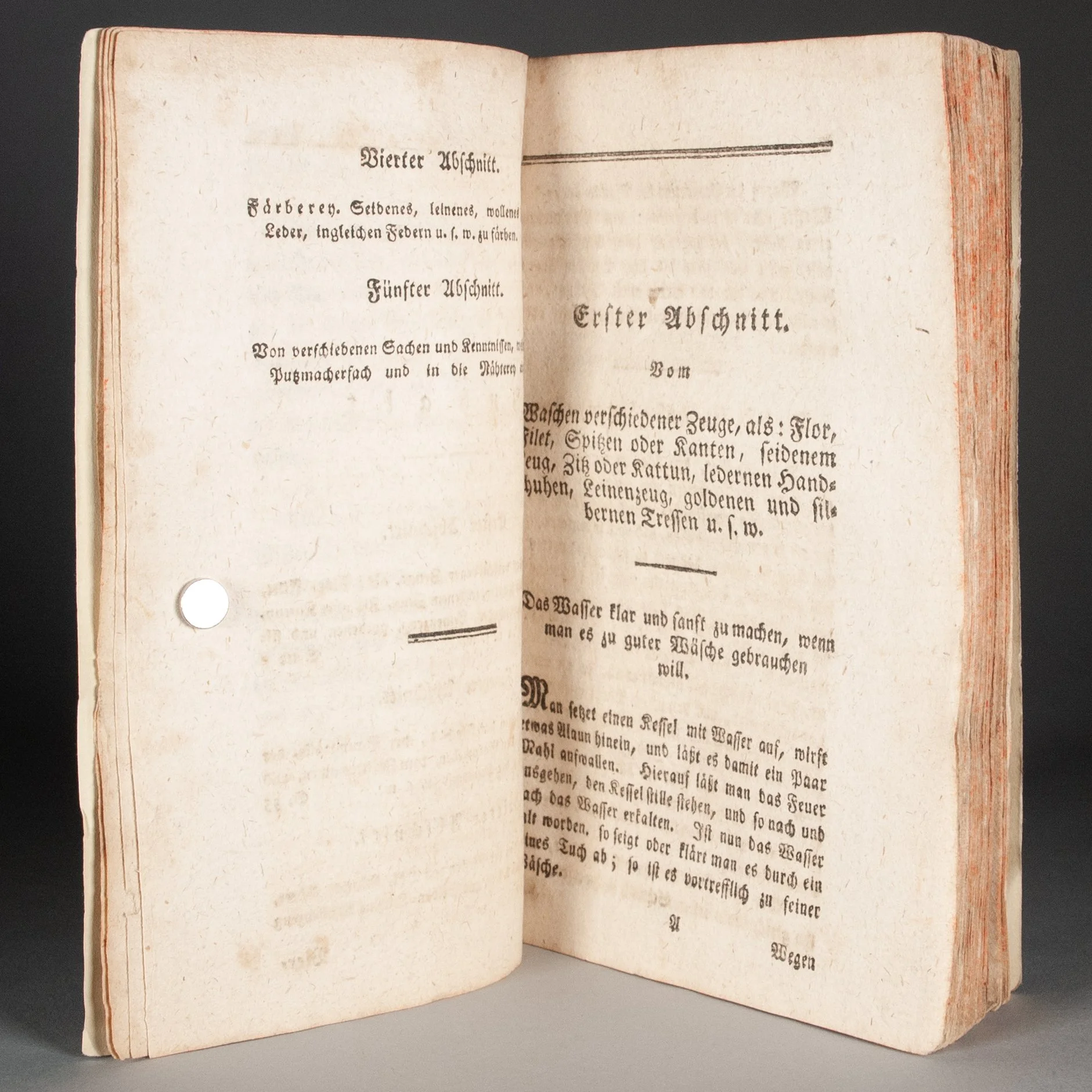

Stated third edition of this guide for charwomen and seamstresses in Vienna, by an anonymous woman who identifies herself with those very trades (besides addressing the book to her "fellow sisters," note the preface signed Herausgeberinn, using the feminine ending inn, and the title signed by a Nähtermädchen, Mädchen meaning girl). Earlier editions appeared in 1798 and 1801, and we find a suspiciously similar Leipziger Putzmacher of 1798. Compared to the relatively more common woman-authored texts on cooking, or comprehensive guides to maintaining the family home, this one offers a less familiar book-length feminine perspective on this ubiquitous women's work. ¶ The book's five sections cover the basics of these trades, everything required "to make a complete and true milliner and seamstress" (*3v). These chapters cover washing and caring for various fabrics, making thread, removing stains, dyeing fabric and leather, and a final section of miscellanea that any milliner or seamstress should know. This latter section provides detailed instructions for making flowers from isinglass; making flowers from wax, including artificial leaves made from paper, and the gilding or silvering of said leaves; making artificial fruit from wax, pitch, or alum, and then how to color said fruit; making flowers from Dutch linen; restoring color to faded fabrics; and then quite a few pages on making and caring for bedding (p. 166: a feather bed requires at least 200 geese for the requisite 50 pounds of feathers!). With a final leaf of publisher's ads promoting seven titles, most of them similarly with a domestic focus. ¶ The title, addressed to the author's Mitschwestern, clearly indicates she was writing for the distaff side. Exactly which women is less clear, though her language tends to invite a broad audience, from those who do this work for a living to everyday housewives and beyond. On p. 168, for example, the author notes that "no good housewife or her seamstress" will allow large feathers to mix with the finer sort best suited for bedding. The author even hopes to satisfy those motivated by simple curiosity. In the opening of her chapter on spinning thread, she forestalls complaints from readers who might suggest this particular topic should have no place in such a book. She kindly disagrees, noting that "anyone who is fortunate enough not to have to do it out of necessity must at least be able to talk about it" (p. 35). The author insists that she herself knows "several ladies of standing who derive real pleasure from spinning and similar activities." ¶ Despite evidence that women’s opportunities for paid work decreased as the early modern period advanced, millinery was one in which women played a growing role. Stripping the beaver and rabbit pelts, for example—a laborious task—was primarily done by women, as was the final stage of decoration. Throughout the seventeenth century, the work of making clothes for sale was largely men’s work. “By the eighteenth century this would shift. Millinery and dressmaking became a ‘female pursuit’” (Manlow). At least in Lyon, by 1781, women in the hatting trade "even had formed 'combinations,' perhaps with the intention of one day receiving guild status" (Farr). ¶ Scarce. We find the 1798 edition at Stanford and Duke, but no WorldCat record for this 1803 edition. At auction, we find a single sale of the 1798 edition, and just one other appearance of this 1803 edition.

CONDITION: Recent marbled wrappers. ¶ A bit of foxing, and an ink stain on the title, but really quite nice.

REFERENCES: Not in VD18 ¶ Veronica Manlow, Designing Clothes: Culture and Organization in the Fashion Industry (2009), p. 35 (cited above, via Wendy Gamber, The Female Economy, 1997); James R. Farr, Artisans in Europe 1300-1914 (2000), p. 110 (cited above), 137 (for women's roles in making hats)

Item #634