Protective amulet in pouch

Protective amulet in pouch

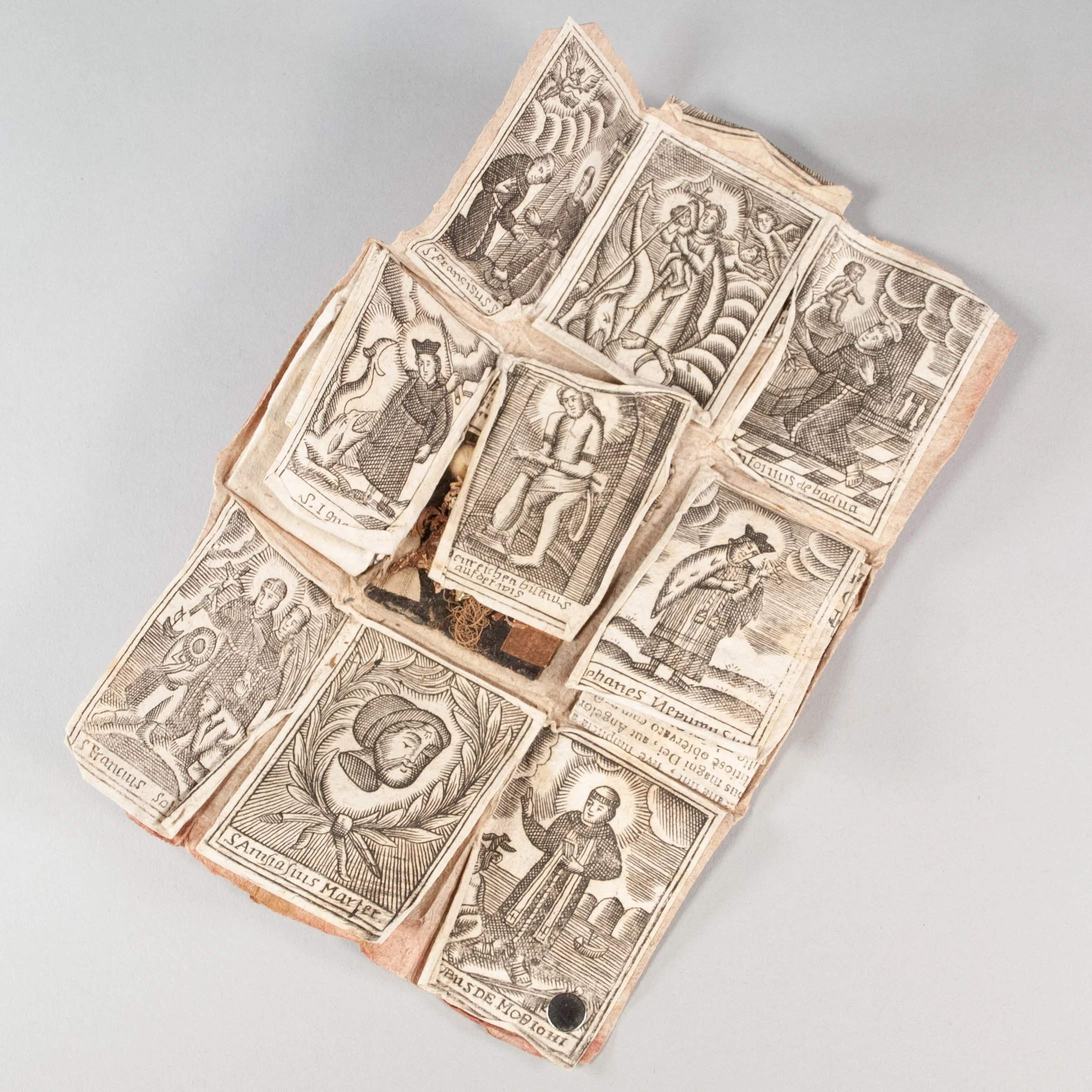

[Breverl — An amulet to ward off demons, disease, and misfortune]

[Bavaria? later 18th century?]

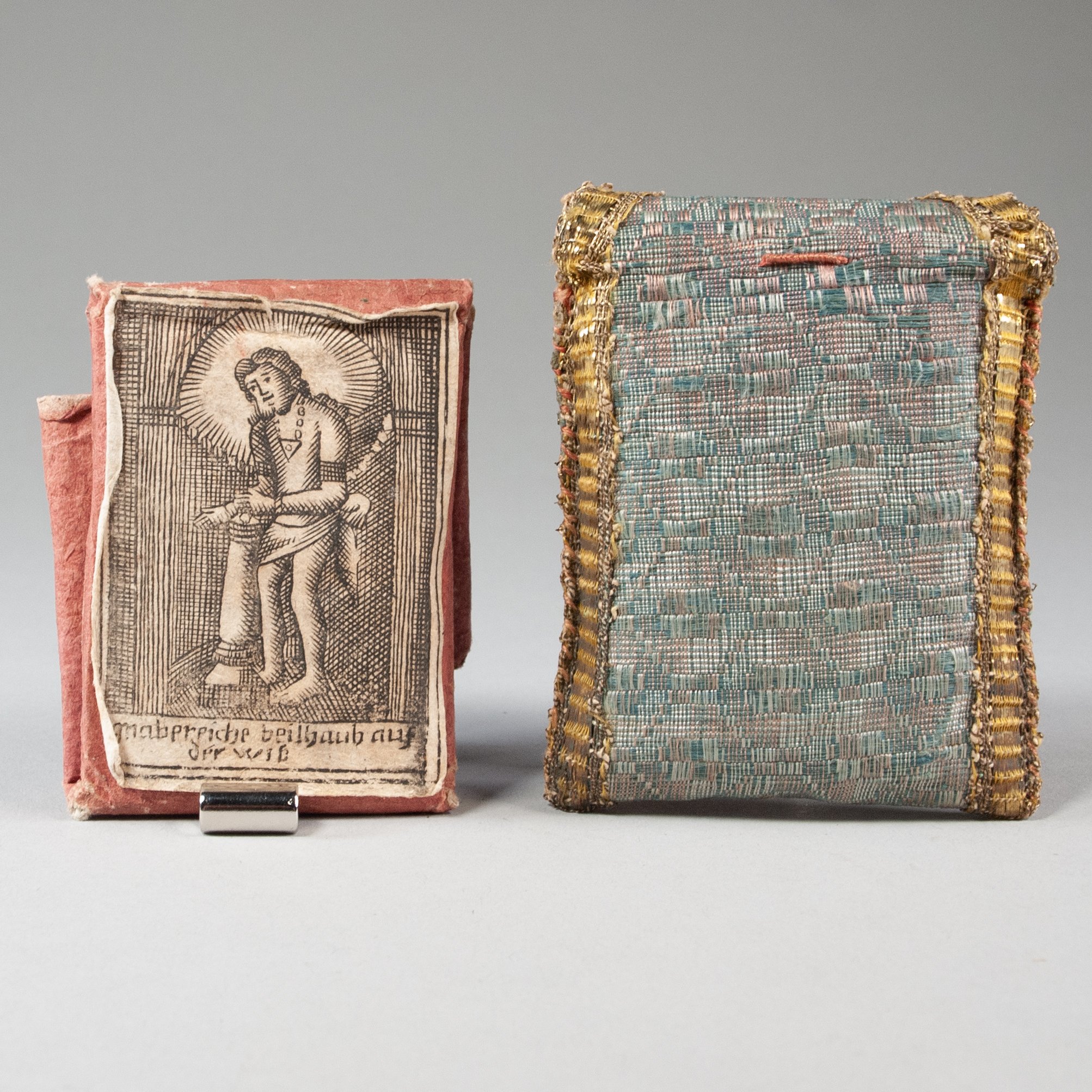

1 folded amulet | 191 x 140 mm folded to 68 x 50 mm in pouch 72 x 64 mm

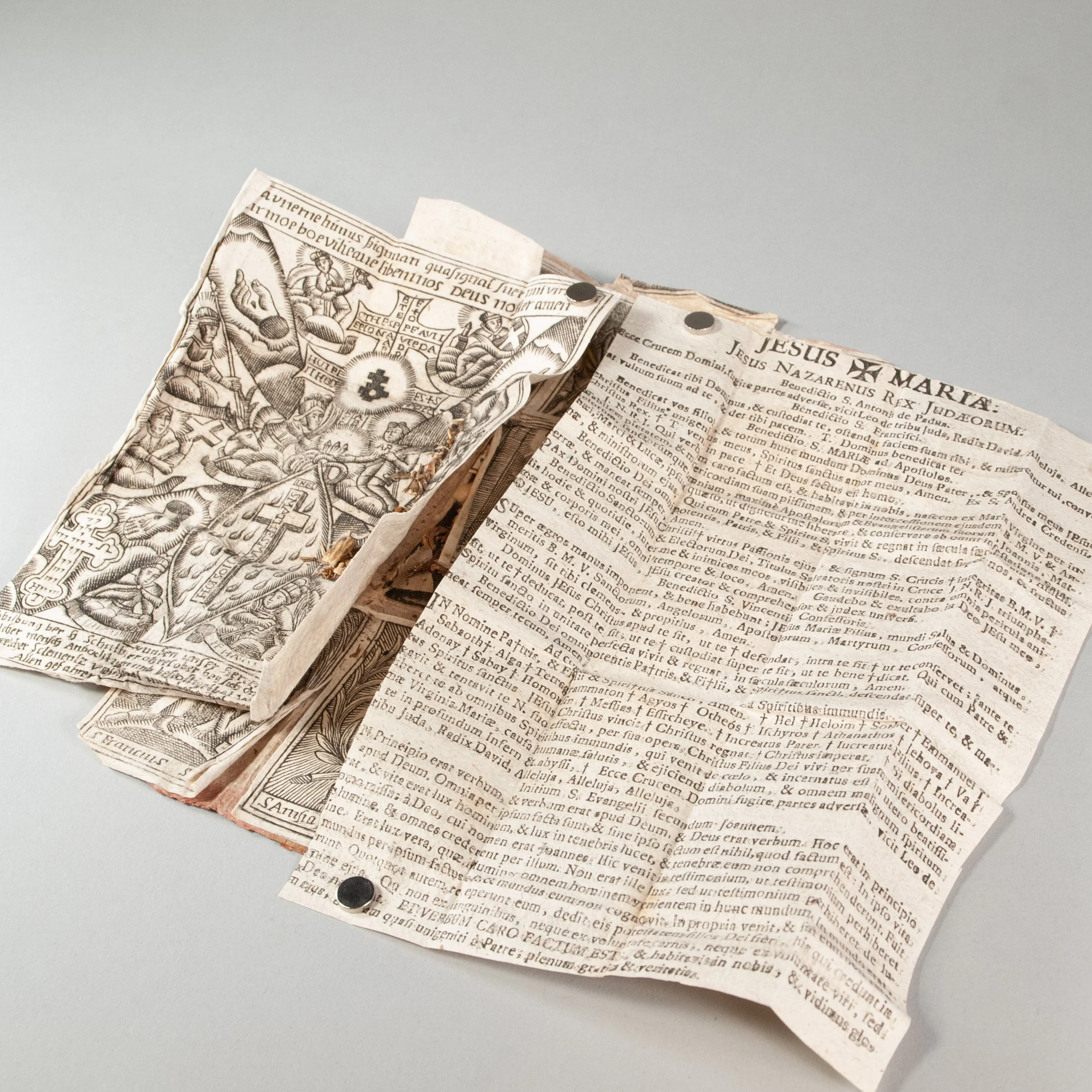

A fantastically multi-layered Breverl, a popular amulet designed to protect its bearer from demons, disease, foul weather, or any other misfortune one might encounter. The genre's name comes from the Latin word for letter or similar brief text, and their production is traditionally associated with nuns. "Originally a plague amulet, the Breverl became in the course of time a panacea owing to its composite character. The opening of its case, whether or metal, silk, velvet, embroidery of paper, was believed to destroy its protective virtues." (Sorry, but we had to catalog it!) "The Breverl was carried on the person, and usually suspended from a string round the neck" (Ettlinger). They're found especially in Europe's Alpine region, Bavaria especially, and most are typically dated to the later 18th century (though they were used both earlier and later). Our source called ours ca. 1780, but these are seldom easy to date with precision. Franciscus Solanus, among those pictured here, wasn't canonized until 1726, providing ours (and many others) with a convenient terminus post quem. ¶ Ours is by all appearances a complete example of the genre, a remarkable "compound amulet" in the words of folklore specialist Ellen Ettlinger. We have the nine religious images in the standard three-by-three layout; the folded prayer sheet typical of the genre in the 18th century (Jesus Nazarenus Rex Judaeorum, with another partially obscured prayer on its verso), pasted under the image at center right; folded under the image at center left, an etching of various crosses and saints, among them what Ettlinger might call "magico-religious texts," this perhaps serving as a Pestkreuz, or plague cross, common to the genre (this with text in both Latin and German, and a variety of organic items stored within its folds, likely blessed grains); and a trove of tiny devotional objects stored among the center panel. Ettlinger would also expect something to represent the Three Magi or St. Agatha, which we do not find here, though it's hard to imagine ours is incomplete. Every interior panel is filled, likewise the two exposed exterior panels when folded. Additional images are pasted beneath the images in the center bottom and center top panels. ¶ The Breverl's apotropaic qualities might best be grasped by considering some of the images found here: Anistasius of Persia, associated with the expulsion of demons and curing of disease; the Virgin and Child, for protection in childbirth; Ignatius of Loyola, further protection from demons; Anthony of Padua, for protection from shipwreck; Johannes Nepomuc, protection from drowning; and Franciscus Solanus, protection from earthquakes. Compare these to an example at Johns Hopkins, for example. Also stored in the central trove are two tin badges, offering further amuletic protection—one a simple arrow, the other a person walking. Outside the Breverl context, and most commonly manifesting as the ubiquitous pilgrim badge, these were typically worn on one’s person, a means to carry with you the protection of the pilgrimage site itself (and to quietly broadcast the news of your accomplishment). Not all badges were pilgrim badges, however. They came in great variety, served multiple purposes, and could be had from many locations. Additional contents include a small piece of bronzed paper, and fragments of plants and textiles. ¶ The central trove contains two amuletic elements more compelling still: two tiny prints, one strictly textual, the other a miniature version of the Anistasius of Persia image, each roughly 12 x 14 mm. These are edible prints, sometimes called Schluckbilder, Schluckbildchen,or Eßzettel. Tiny prints produced specifically for the purpose of consumption must have seemed an inevitability, and they became a brisk business at some monasteries and pilgrimage sites. Often bearing likenesses of the Madonna or Christ, and invariably printed dozens to the sheet, "these were meant to be cut apart and consumed to cure illness or ward off bad luck. A variation on the Host—though most surviving examples are not round—they served as another apotropaic surrogate" (Schmidt). They might be mixed into food or drink, added to baked goods, or made into little pills. No Schluckbildchen? No problem! In Augsburg, farmers allegedly cut images from calendars and ingested them for the same purpose. We know, too, that pages of Bibles were consumed for healing effects as late as the 19th century. Even animals sometimes partook in the Schluckbildchen phenomenon. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the method of use, survivors are rather thin on the ground. The earliest known are 17th-century, most date to the 18th or 19th, and they were used even into the 20th century. ¶ More than the consummate example of a popular genre, this Breverl is no less a storehouse for other fleeting genres of amuletic devotionalia. We find just a handful of Breverl in auction records, none with such a well stocked central panel of devotionalia, and none accompanied by an original carrying pouch.

CONDITION: Everything mounted to a heavy sheet of dark pink laid paper. Folded and accompanied by an old cloth pouch—presumably original, given the superstition about opening them. There's a small red loop on the top backside, from which we suspect a cord was once strung so it could be worn around the neck. The Breverl came to us in its pouch, but we store it separately to reduce wear and tear. ¶ The prints crinkled at the edges from folding; the central image loose, save for being twisted to the corner of its neighbor; the larger sheet generally creased and worn at the edges; arrow badge detached from the central panel, and some seeds and organic matter loose. The pouch a bit soiled, and retaining only pieces of its original silk closure ribbons. Really an impressive survival.

REFERENCES: On Breverl: Ellen Ettlinger, "The Hildburgh Collection of Austrian and Bavarian Amulets in the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum," Folklore 76.2 (Summer 1965), p. 110-111 (cited above, and outlining the contents of a complete Breverl); Suzanne Karr Schmidt, Interactive and Sculptural Printmaking in the Renaissance (2018), p. 54 (Breverl "were some of the most cheaply made movable prints, called Breverl, after the Latin for a short text. The Breverl’s small woodcut images and biblical passages effectively fold down into envelopes that could be filled with relics or scented pastes. Used as amulets dedicated to saints or pilgrimage sites, they were hung on cords around the neck in open metal or leather containers. When worn, one's body heat released the scent of the rosary."); Wolfgang Brückner, Volkskunde als historische Kulturwissenschaft (2000), p. 503 ("A Breverl always consists of nine panels, namely three by three images"), 505 (reference to "their heyday in the mid-18th century"); Peter Ochsenbein, "Zur Typologie der Breverl," Zeitschrift für Österreichische Volkskunde 103.1 (2000), p. 66 ("The Breverl is an impressive document from the religious world of simple [einfachen] people") ¶ On pilgrim badges: Ann Marie Rasmussen, Medieval Badges: Their Wearers and Their Worlds (2021), p. 12 (“Displayed on capes and hats as people went about their business, badges were mobile, because they moved through space with their wearers. This mobility meant virtually everyone in Northwestern Europe in the Middle Ages would have encountered badges in some way, and virtually everyone could have afforded one because as mass-produced objects made of easily obtained and widely available materials, they were cheap.”), 13 (“Badges were worn: they were made to be worn, they are shown being worn, and the fact that they are found hundreds of kilometers from the sites to which they refer shows as that they were carried and worn far from their sites of origin.”); Esther Cohen, “In haec signa: Pilgrim-badge trade in southern France,” Journal of Medieval History 2.3 (1976), p. 194 (at pilgrimage sites, “Perhaps the most profitable trade of all was the sale of pilgrims’ badges…Pilgrims brought them home as souvenirs and as testimony of the accomplished pilgrimage…From decorative souvenirs, they became indispensable evidence of a performed pilgrimage. No pilgrim would return home without first having purchased a badge. The same badge, worn on the return journey, ensured its bearer protection from warring armies and other threats of violence.”); Megan H. Foster-Campbell, “Pilgrimage through the Pages: Pilgrims’ Badges in Late Medieval Devotional Manuscripts,” Push Me, Pull You: Imaginative and Emotional Interaction in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art (Brill, 2011), v. 1, p. 227 (“pilgrimage to popular holy shrines peaked in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. To remember their visits, pilgrims often purchased small, inexpensive souvenirs—usually thin, metal badges—which were manufactured and sold near pilgrimage churches.”), 231 (“These badges were in close proximity or perhaps even direct contact with the holy shrine, often by being touched or pressed against the shrine to imbue them with miraculous powers, in effect making the badge a contact relic. When worn by a pilgrim, the souvenir could serve a talismanic or apotropaic function, capable of warding off evil and protecting the individual from harm.”) ¶ On Schluckbildchen: Duane J. Corpis, "Marian Pilgrimage and the Performance of Male Privilege in Eigtheenth-Century Augsburg," Central European History 45.3 (Sept 2012), p. 403 ("The sick and despondent would cut individual squares from the strip and swallow them for curative effect"); Suzanne Karr Schmidt, Interactive and Sculptural Printmaking in the Renaissance (2018), p. 52 (cited above; "No fifteenth or sixteenth-century impressions survive, suggesting they were indeed consumed"); Suzanne Karr Schmidt, Altered and Adorned: Using Renaissance Prints in Daily Life (Art Institute of Chicago, 2011), p. 68 ("On the lowest end of the devotional print schema were images that were meant to be literally consumed. These referred to specific cult images, and having the sheets blessed at the relevant shrine would have all but guaranteed their efficacy...The images were generally repeated to maximize the number offered at once, making full use of the sheet. These little tabs were in fact meant to be cut out and eaten (or rolled up and taken with water) to stave off disease or even black magic. Some were fed to ailing livestock, or combined into baked goods as a further apotropaic remedy. The earliest surviving sheets of this type date to the seventeenth century."); Erwin Richter, "Einwirkung medico-astrologischen Volksdenkens auf Entstehung und Formung des Bärmutterkrötenopfers der Männer im geistlichen Heilbrauch," Sudhoffs Archiv für Geschichte der Medizin und der Naturwissenschaften 42.4 (1958), p. 345 (for the cutting of images from calendars); Patrick J. Donmoyer, "The Concealment of Written Blessings in Pennsylvania Barns," Historical Arcchaeology 48.3 (2014), p. 188 (for their animal use, describing Schluckbildchen as "images of Roman Catholic saints and biblical verses printed in multiples on sheets of paper that were intended for consumption by humans and animals"); Margarethe Ruff, Zauberpraktiken als Lebenshilfe: Magie im Alltag vom Mittelalter bis heute (2003), p. 154 (Schluckbildchen were at times a flourishing business in some monasteries and were in use until the 20th century...These were taken in water or pressed [gedreht] into pills."); William H. Sherman, Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England (2008), p. 84 (on the eating of Bibles); David Pearson, Speaking Volumes: Books with Histories (Bodleian, 2022), p. 169 ("there is a story of a nineteenth-century woman who ate a page of a New Testament in a sandwich, day by day, to improve her health"); Thomas Staubli, Werbung für die Götter: Heilsbringer aus 4000 Jahren (2003), p. 139 (describing an 18th-century Bavarian sheet: "In many cases, they [pilgrims] fulfilled an order from relatives and neighbors who supplemented their medicine cabinet with Schluckbildchen"); Ritchie Robertson, "The Reform of Catholic Festival Culture in Eighteenth-Century Austria: A Clash of Mentalities," Austrian Studies 25 (2017), p. 34 (these were among the breadth of available pilgrim souvenirs, "tiny images of the Virgin to swallow when ill"); Maciej Mętrak, "Give the Devil His Due: Demons and Demonic Presence in Czech Broadside Ballads," Czech Broadside Ballads as Text, Art, Song in Popular Culture, c.1600-1900 (2022), p. 218 ("woodcuts were used in magical and apotropaic roles (for example, to create devotional pictures for swallowing," these "used as a magical remedy in folk medicine")

Item #922