Lady Anne Monson's Linnaeus translation

Lady Anne Monson's Linnaeus translation

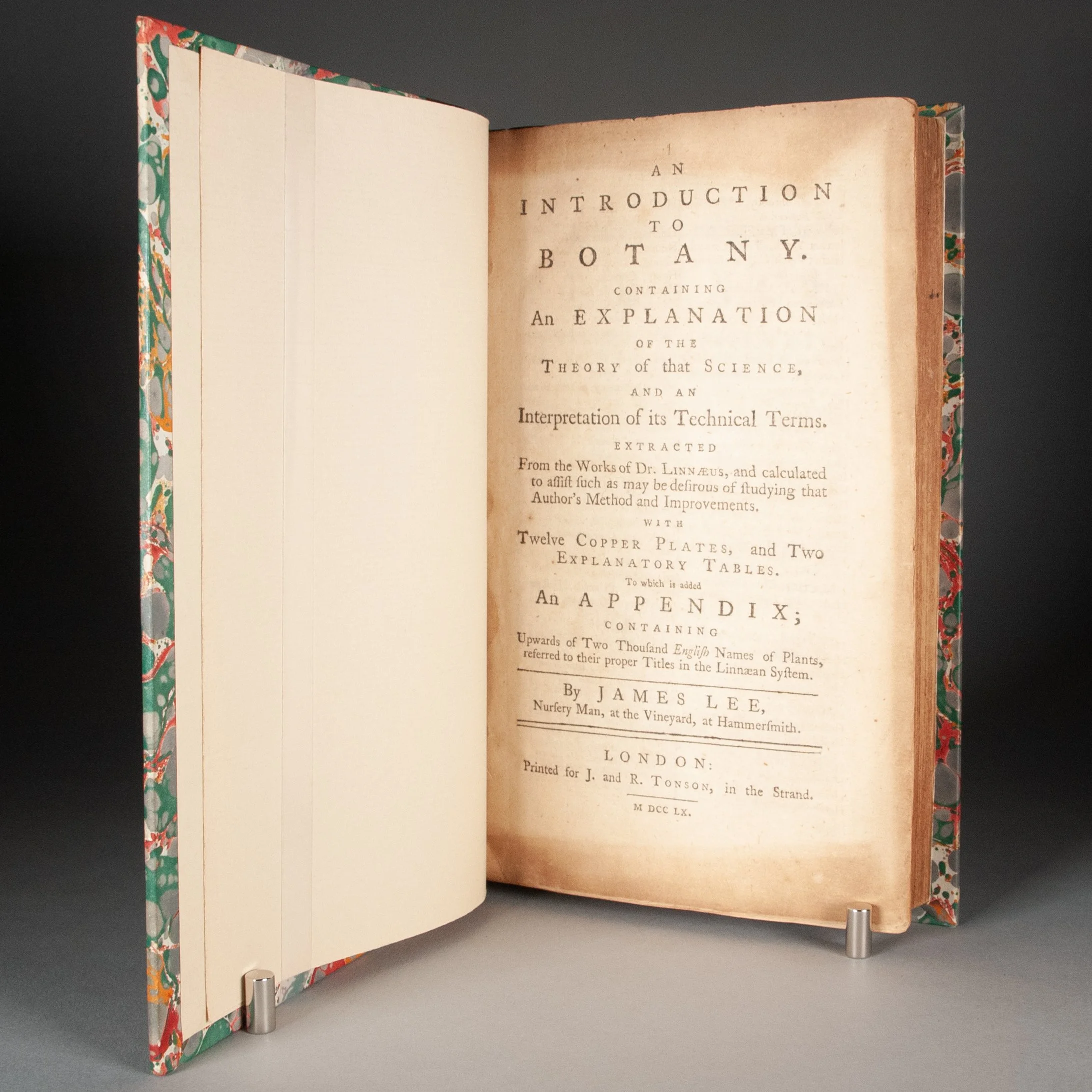

An introduction to botany, containing an explanation of the theory of that science, and an interpretation of its technical terms; extracted from the works of Dr. Linnaeus and calculated to assist such as may be desirous of studying that author's method and improvements; with twelve copper plates and two explanatory tables; to which is added an appendix, containing upwards of two thousand English names of plants, referred to their proper titles in the Linnaean system

by Carl von Linné (Linnaeus) | translated and edited by James Lee and Lady Anne Monson

London: J. and R. Tonson, 1760

xvi, 320, [24] p. + 12 plates | 8vo | A-U^8 X-Y^4 | 205 x 125 mm

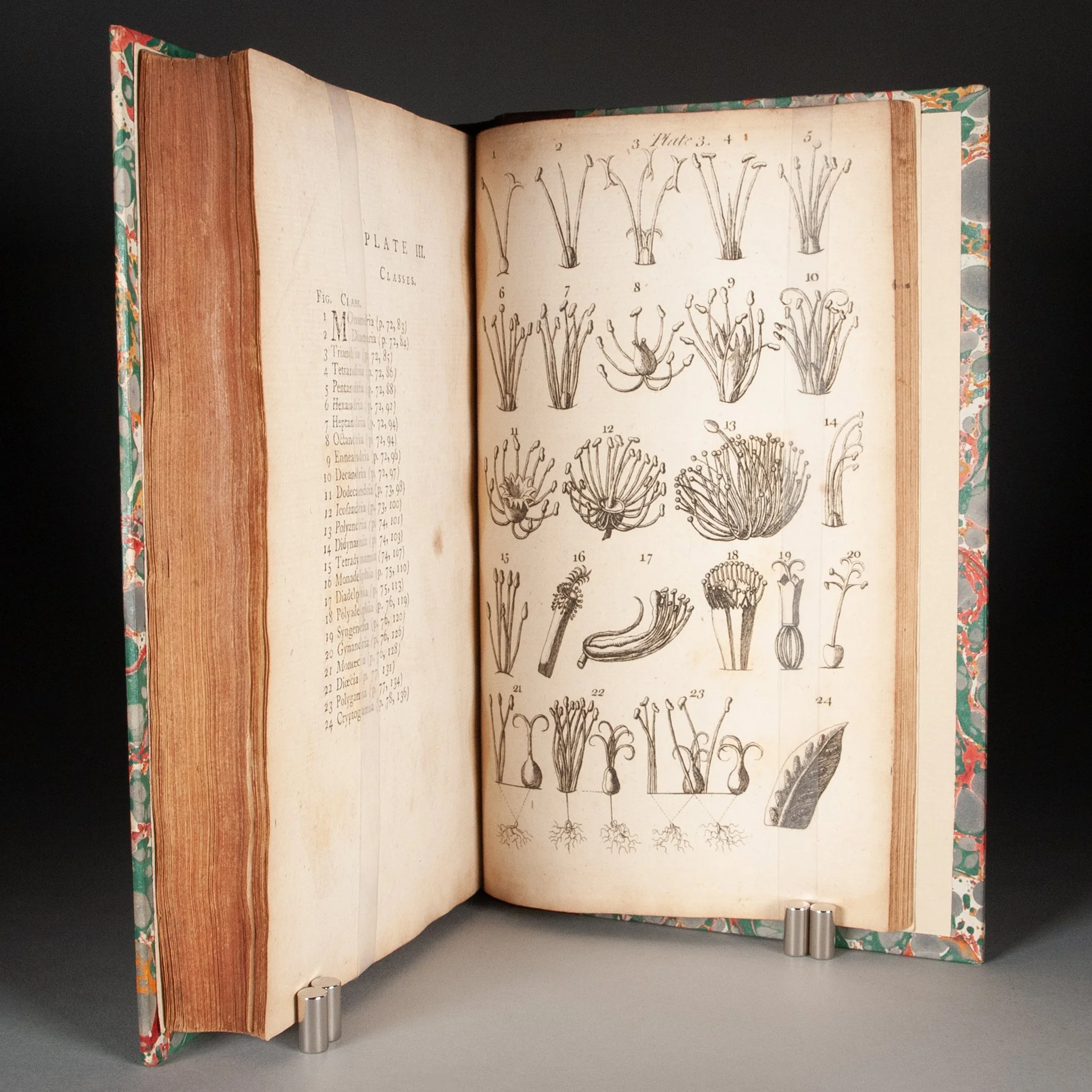

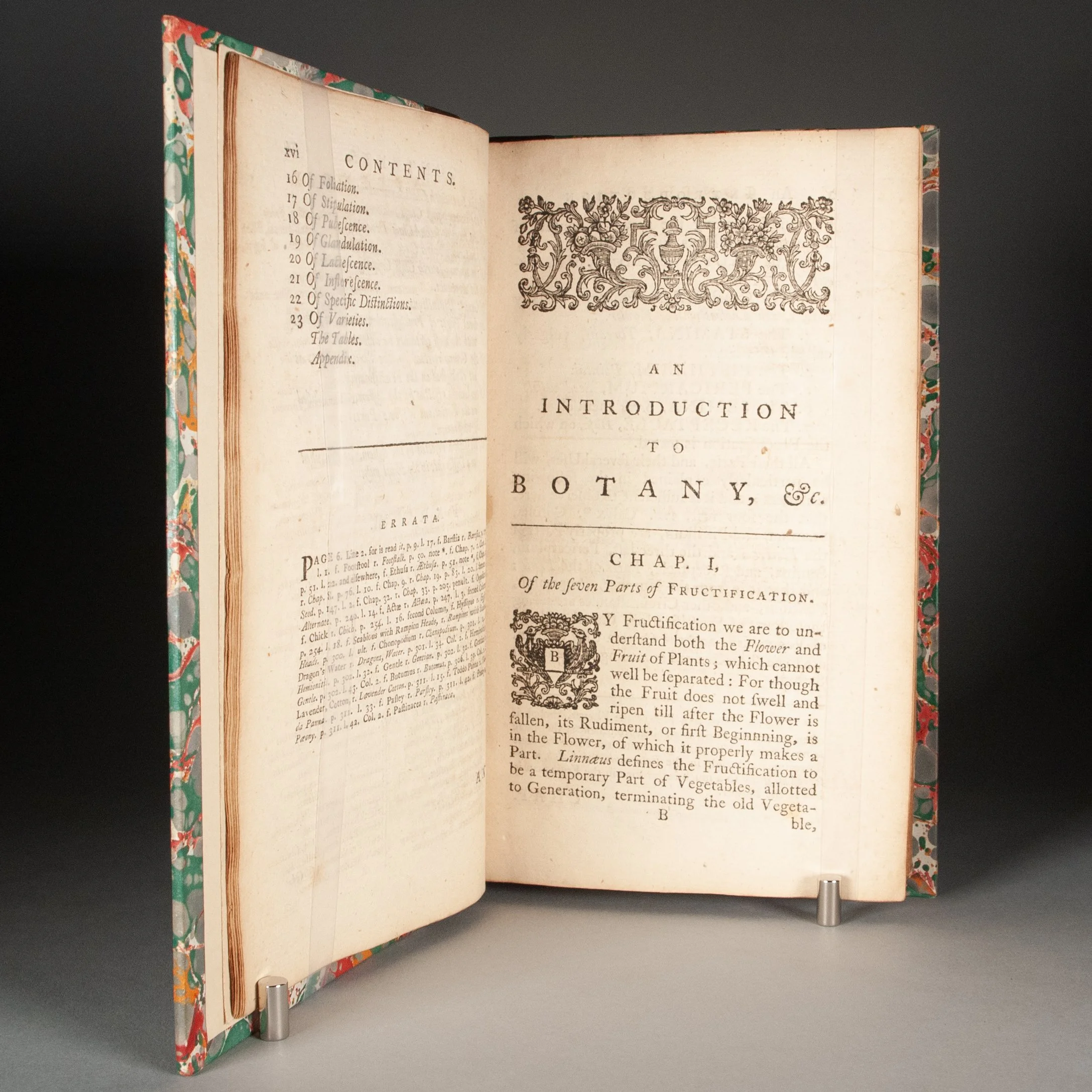

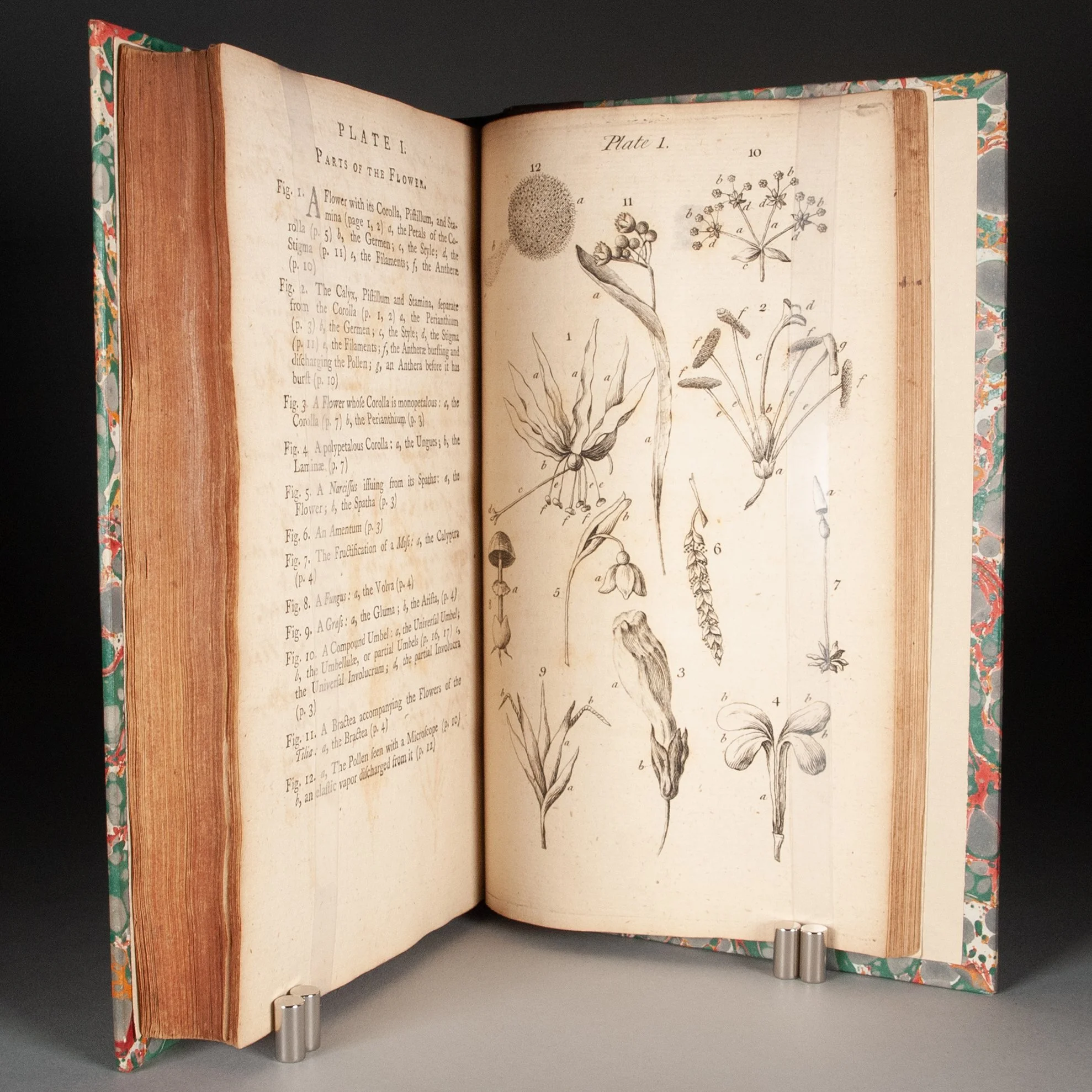

First edition of "the first attempt to translate the works of Linnaeus into English" (Willson), a compilation that drew on a number of the famed Swedish biologist's published works, his Philosophia Botanica especially. A number of editions followed through at least 1811, and the work did much to popularize the Linnaean system among English speakers. ¶ Despite Lee's prominent placement on the title page, he ends his preface eager to disavow readers of any notion "that he is of sufficient Strength to undertake a Work of his Kind without Assistance" (p. xii). His unnamed assistant was Lady Anne Monson, a well educated great-granddaughter of Charles II. "Lee began work on Monson's suggestion that a [Linnaeus] version in English would be useful to those who had not learnt Latin. The book comprised an edited selection of writing from various of Linnaeus' works, possibly aimed at a female audience" (Fry and Wayland). Monson possessed a working knowledge of several languages, Latin among them, and came to befriend and correspond with Linnaeus himself. En route to Calcutta in 1774, she met Carl Peter Thunberg, one of Linnaeus's brightest students. During a stop at the Cape of Good Hope, Thunberg's local knowledge proved a great boon to Monson's collection of rare botanical specimens. Her collecting continued when she reached India, and Linnaeus immortalized her with his Monsonia genus of plants. She died in Calcutta in 1776. ¶ Across three primary divisions, Lee and Monson cover the sexual reproduction system of plants; Linnaeus's twenty-four classes of plants; and plants' parts, characteristics, and processes more broadly. The final third of the volume contains a pair of tables, the first mapping Latin names to their English equivalents, and the second the English names to Latin. At end are twelve plates, each accompanied by a page of explanatory letterpress text, illustrating the parts of plants and their fruit, different leaf shapes, the different classes, etc. ¶ Not terribly common in the trade. We find half a dozen appearances in auction records.

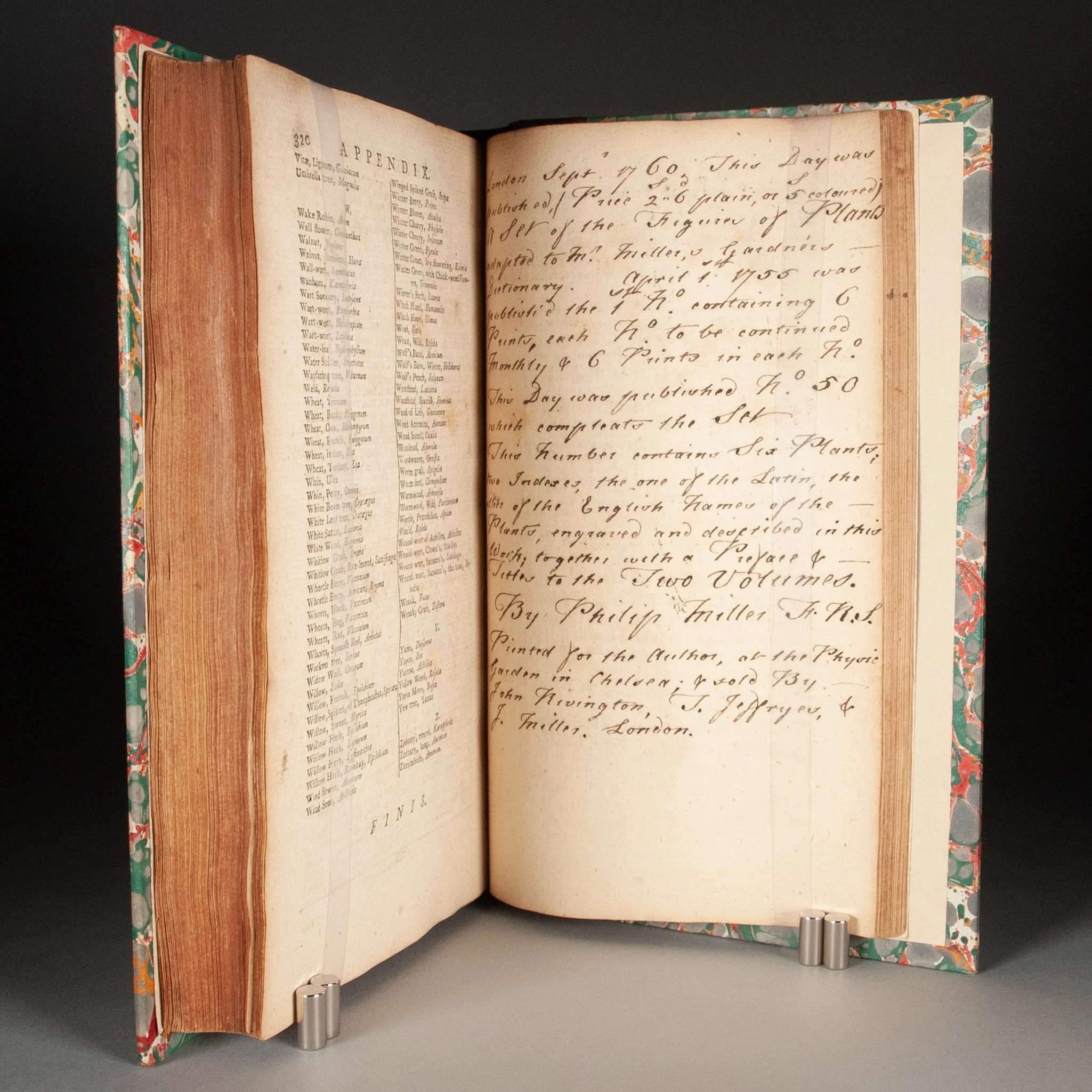

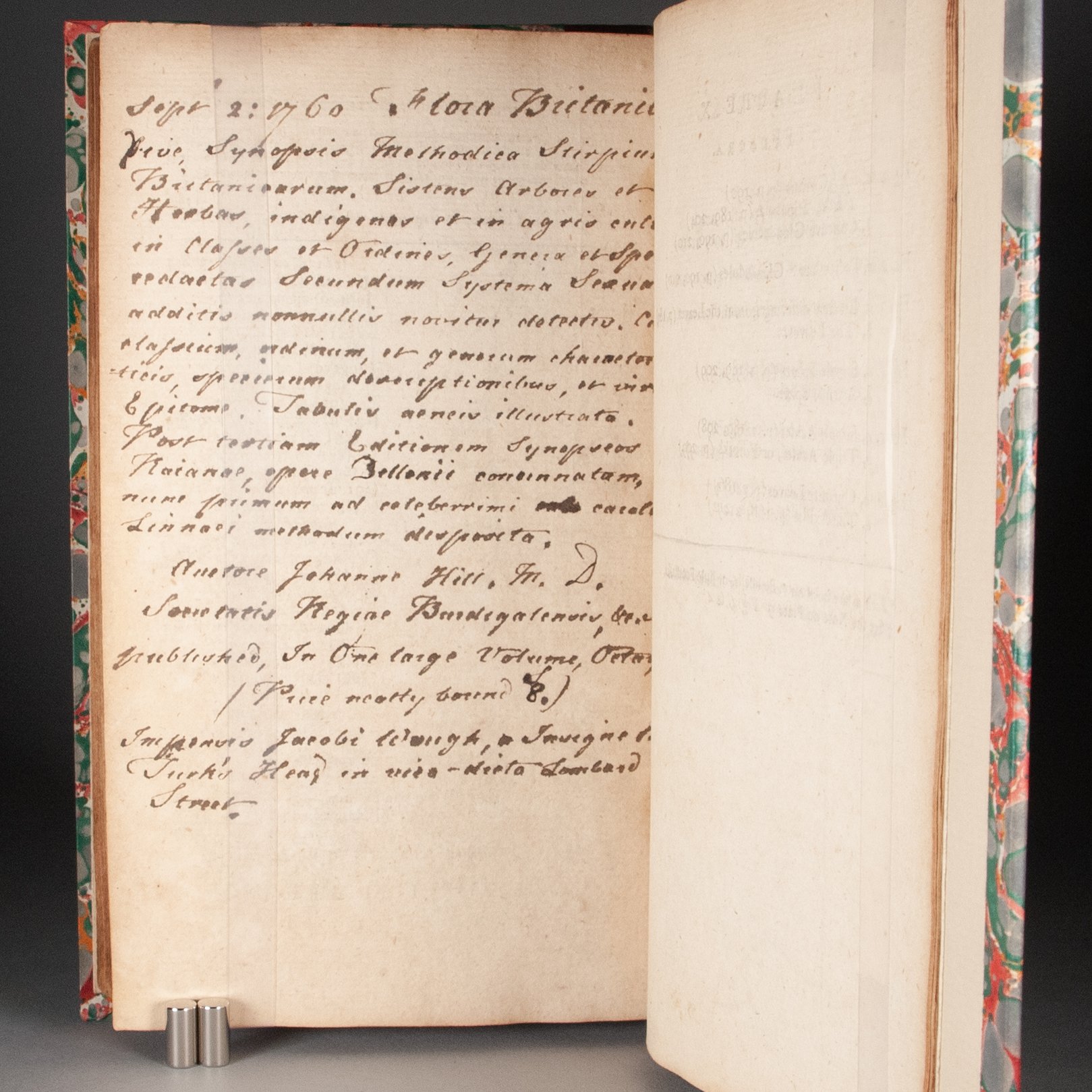

PROVENANCE: On the blank recto of the letterpress leaf explaining Plate 1 are contemporary handwritten details on the publication chronology of Philip Miller's Figures of the Most Beautiful, Useful, and Uncommon Plants (ESTC T59417). This collection of 300 plates, meant to illustrate Miller's Gardener's Dictionary, was published in parts 1755-1760. Our note is dated [1st?] September 1760 and records publication of the fiftieth and final number of the series (and provides a convenient, more detailed terminus ante quem for publication of Lee and Monson's work). Our annotation also notes the first number was published on 1 April 1755, contradicting ESTC, which says the first number "was delivered to subscribers" on 25 March 1755. ¶ The blank recto of the leaf accompanying Plate 9 bears a similar inscription, dated 2 September 1760, noting the publication of John Hill's Flora Britanica (ESTC T35615).

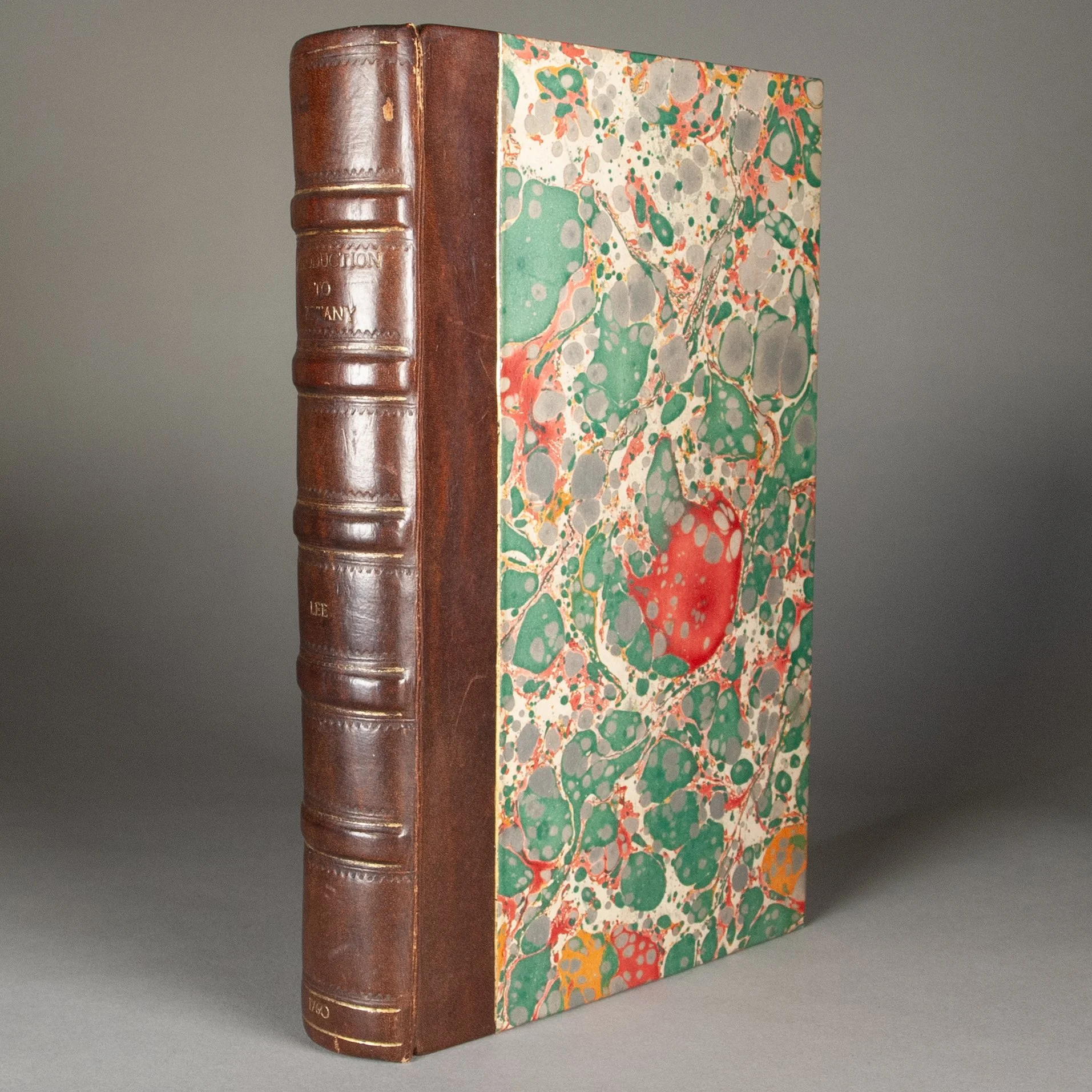

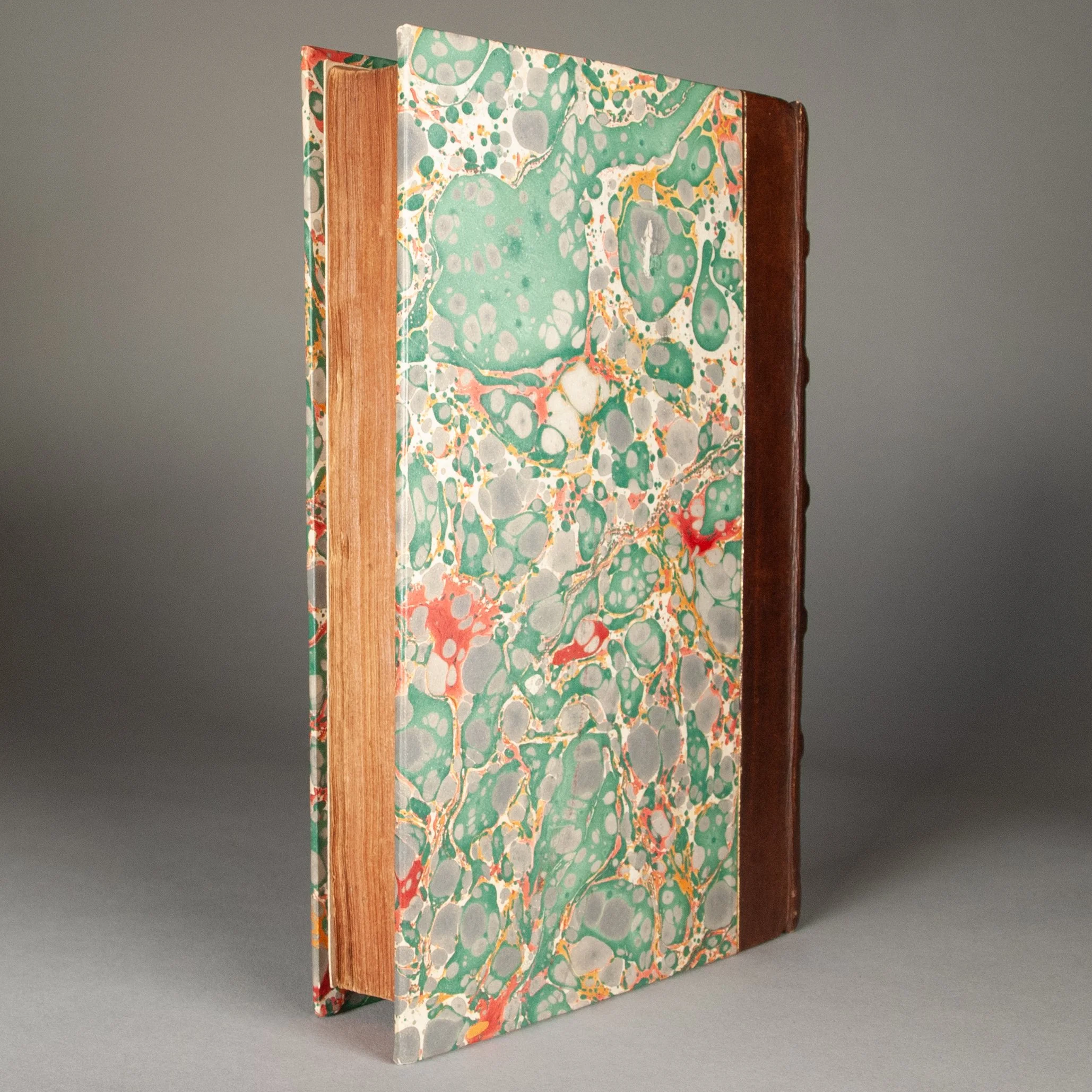

CONDITION: Recent quarter leather and marbled boards, the spine tooled in gilt and blind. The letterpress leaves accompanying the plates are not included in our signature statement. ¶ Plate 9 and its letterpress accompaniment bound in upside down, presumably so the annotation appears right side up; first and last few leaves darkened at the edges; mildly foxed throughout. Gilt on spine dulled, and the binding extremities just gently rubbed. Really a nice copy.

REFERENCES: ESTC T81054 ¶ Eleanor J. Willson, James Lee and the Vineyard Nursery, Hammersmith (1961), p. 19 (cited above; "the distinguishing merit of Lee's work is that it abounds with examples"); James Britten, "Lady Anne Monson (c. 1714-1776)," The Journal of Botany, British and Foreign, v. 56 (1918), p. 148 (cited above; "Lady Ann Monson, a lady of distinguished talents, as well as of eminent botanical taste and knowledge, who by a long residence in the East Indies had great opportunities of cultivating the study of plants, as well as insects...We trust we shall betray no inviolable secret, in recording that it was to this lady that the late Mr. Lee alluded in the preface (p. xii) to his Introduction to Botany, first published in 1760, where he says he was enjoined not to acknowledge his obligations to those who had kindly helped him in his undertaking"); Deidre Shauna Lynch, "'Young Ladies Are Delicate Plants': Jane Austen and Greenhouse Romanticism," ELH 77.3 (Fall 2010), p. 690 (attesting its role among other texts of popularizing Linnaeus); Mary R.S. Creese, Ladies in the Laboratory III (2010), p. 2-3 (brief bio of Monson); Carolyn Fry and Emma Wayland, The Botanists' Library: The Most Important Botanical Books in History (2024), p. 140 (cited above; "his Linnaeus edition was so successful that it cornered the market in English until the end of the eighteenth century and beyond"); Marilyn Ogilvie and Joy Harvey, The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science (2000), v. 2, p. 908 (another brief bio; "In her forties, she worked with the nurseryman James Lee on his book Introduction to Botany, published in 1760, but wished to remain anonymous")

Item #924