Essential Elizabethan schoolbook | Dedication by the author's widow

Essential Elizabethan schoolbook | Dedication by the author's widow

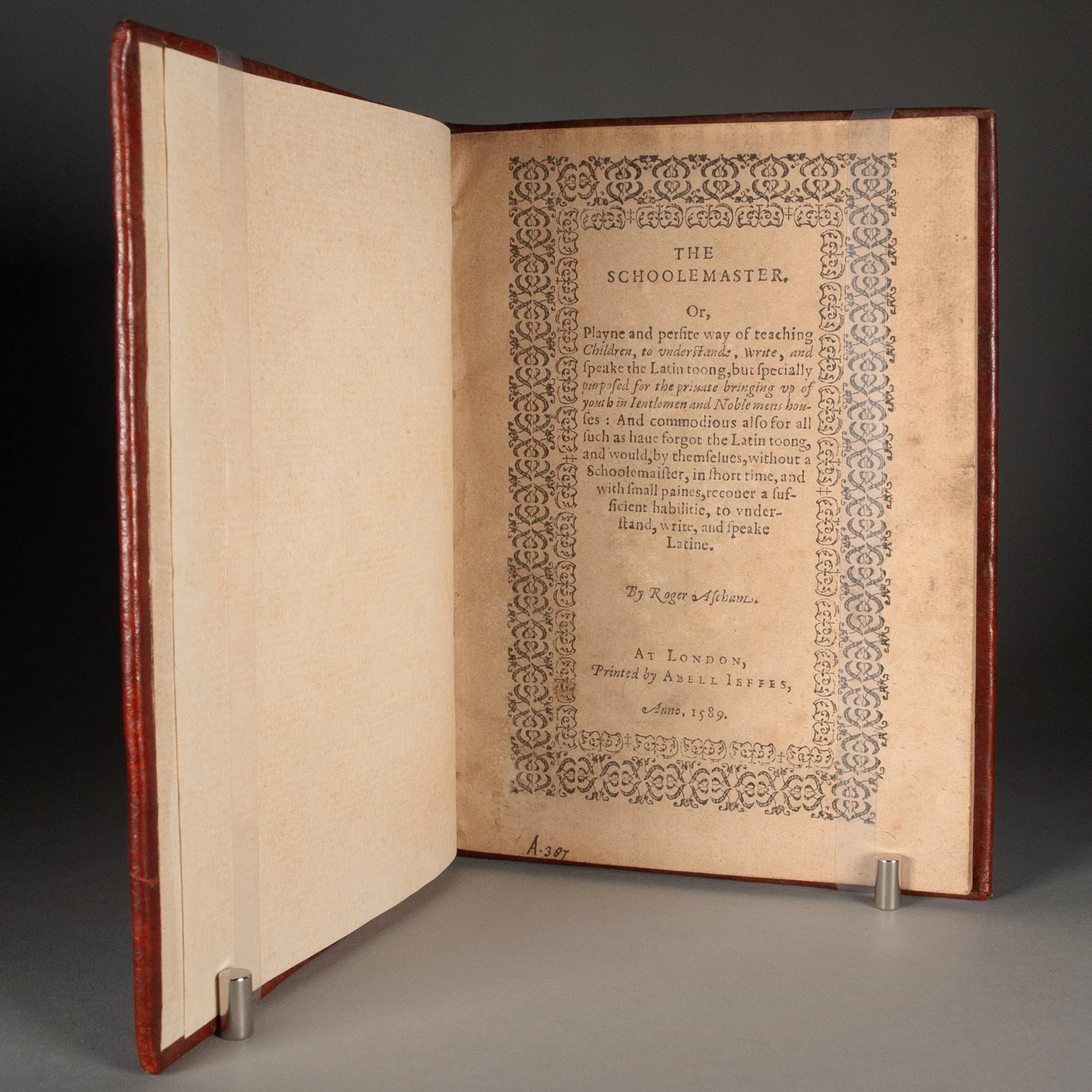

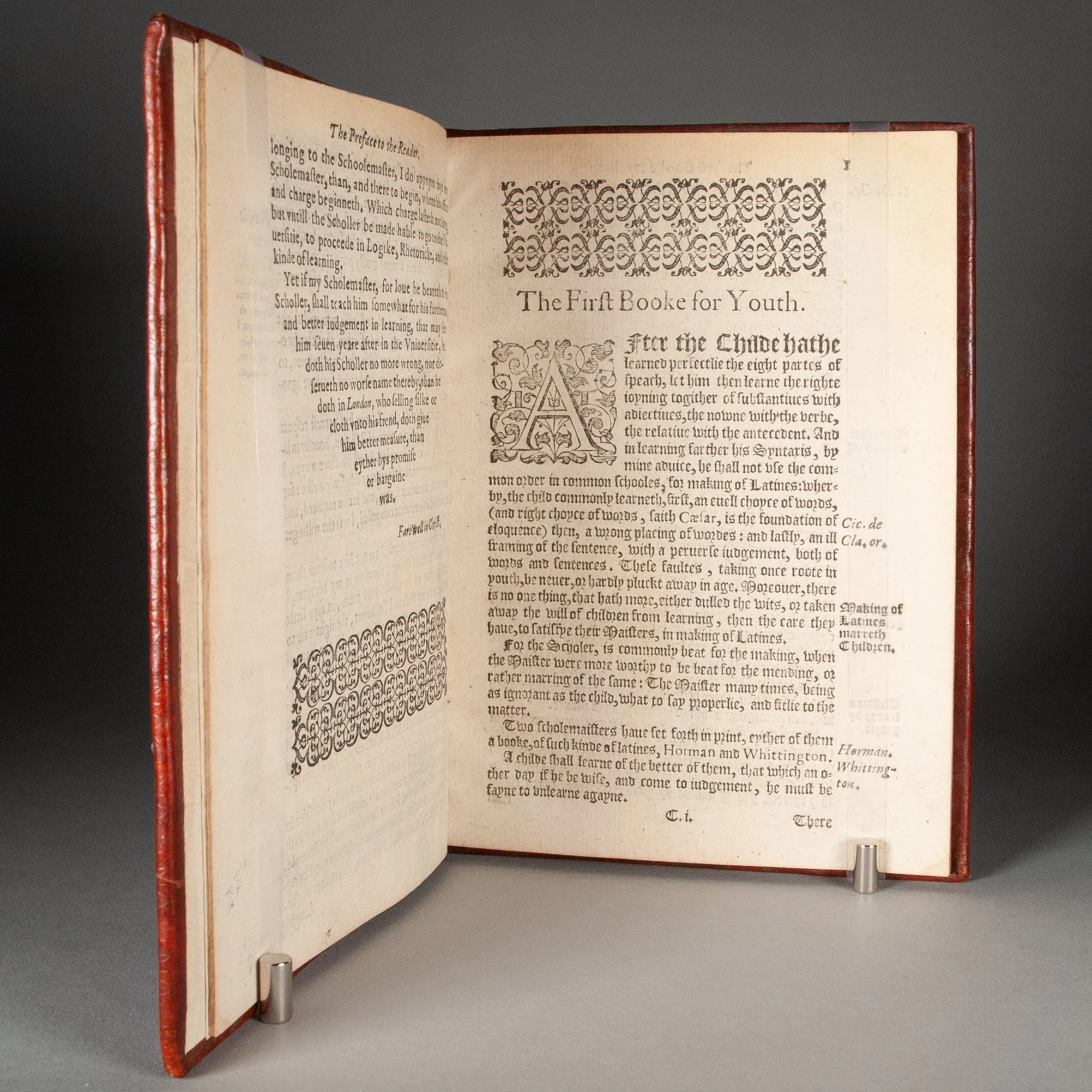

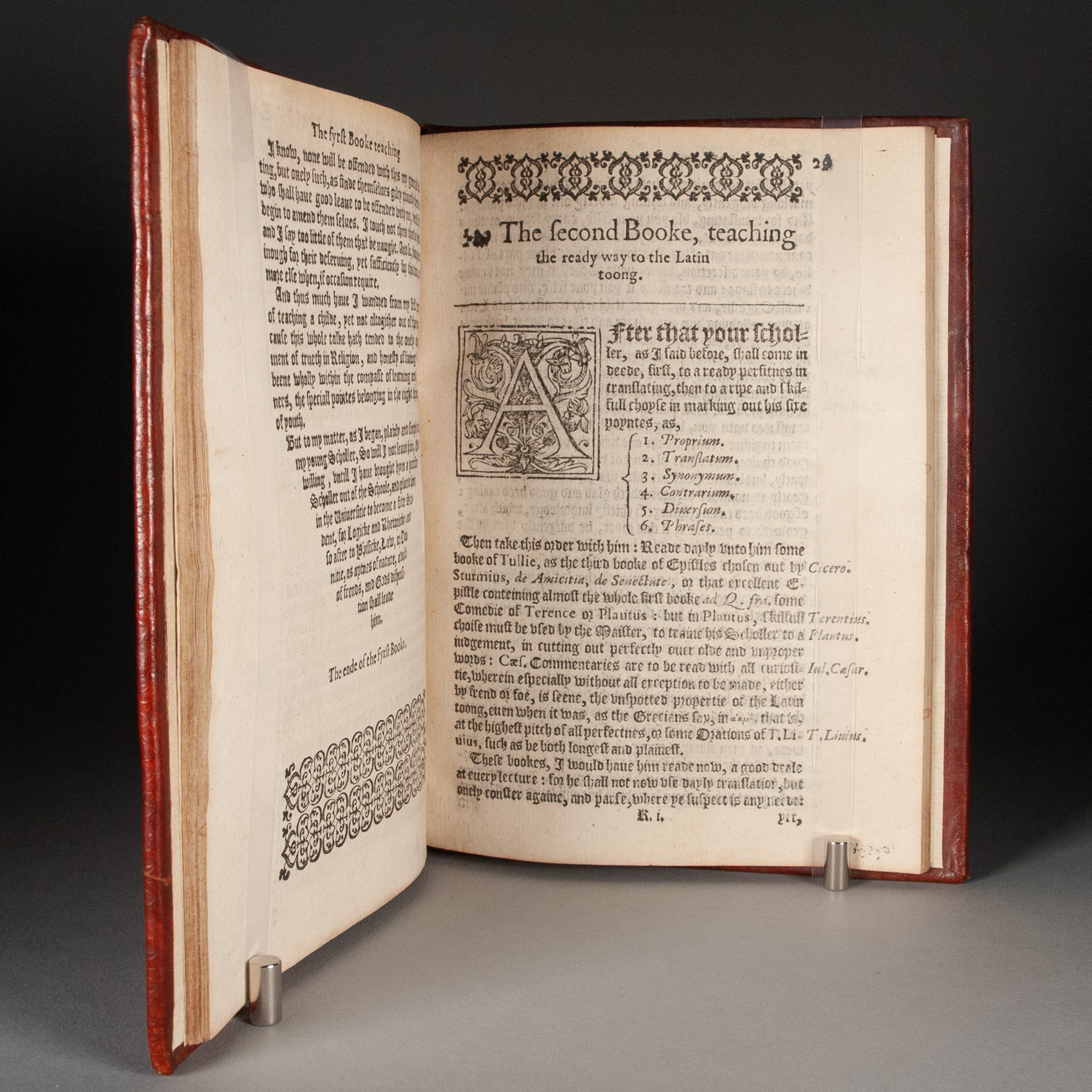

The schoolemaster, or, Playne and perfite way of teaching children to understande, write, and speake the Latin toong, but specially purposed for the private bringing up of youth in jentlemen and noble mens houses; and commodious also for all such as have forgot the Latin toong, and would, by themselves, without a schoolemaister, in short time and with small paines, recover a sufficient habilitie to understand, write, and speake Latine

by Roger Ascham | dedication by Margaret Ascham

London: Abel Jeffes, 1589

[6], 39 leaves, fol. 39, 37-44, 46-60, [1] leaves | 4to | A^2 B-S^4 | 185 x 136 mm

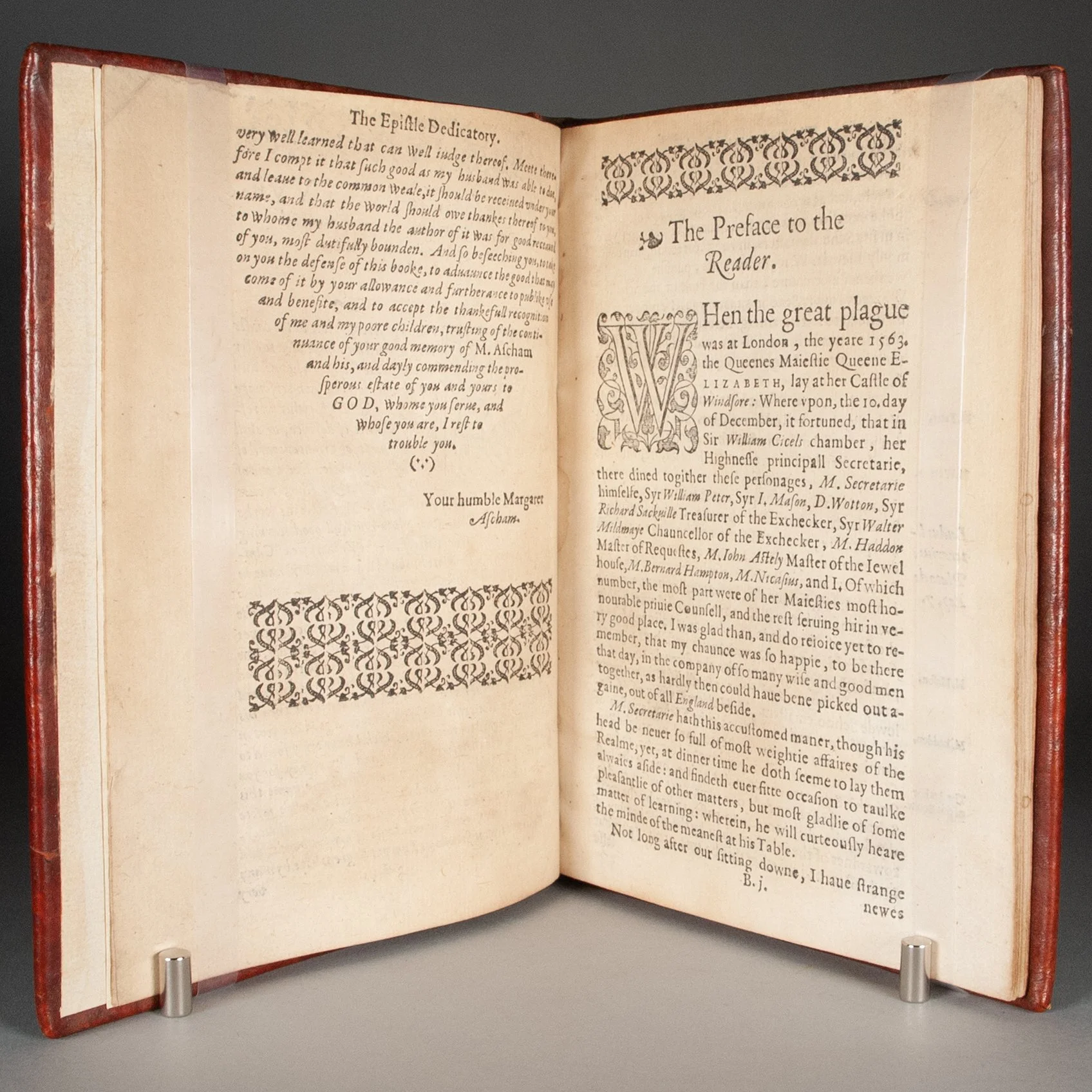

The fifth edition of this indispensable piece of Elizabethan pedagogy, "the most celebrated schoolbook written in English at the time" (Maslen). The first edition appared in 1570, followed by others in 1571, 1573, and 1579. This was the last edition until James Upton's revision of 1711. ¶ Ascham struggled to secure academic stability early in his career, but the success of his Toxophilus saw to that, and in 1548 Princess Elizabeth requested that he serve as her private tutor. As collateral damage in court scandal, Ascham spent some time in Germany, but returned to England in 1553. He hoped to rebuild his presence at court, and indeed succeeded in becoming Queen Mary's Latin Secretary. He was well received in Elizabeth's court, too, following her accession in 1558, and the two were known to read together after dinner. He was never rich, struggled with gambling, and seemed frequently to be unhappy. "This book," however, "which popularized the educational views of Renaissance Englishmen, has made Ascham famous among educational theorists, and one of the most influential of their number" (O'Day). But his fame proved posthumous. Ascham died in 1568, and his wife, Margaret, ushered the book through publication, hence her name attached to the dedication. ¶ Despite his disparagement of all things Italian, Ascham took Quintilian as his pedagogical model, the first-century Roman rhetorician, "applied so as to persuade rather than force English young people to live, speak, and write well" (Trapp). Ascham counsels against the harsh punishment of students, and suggests the study of Latin should be a pleasant experience. To be sure, the Schoolmaster's origin story is found in a pair of conversations bearing on the topic. In the first, Ascham heard that some students had fled Eton in fear of corporal punishment. In the second, Richard Sackville confided that beatings at the hands of his own schoolmaster had put him off learning. Despite the classical model he found in Quintilian, Ascham was little interested in cultivating the stylistic flairs that might distinguish the ambitious humanist academic, but rather produced this work to train the courtier class. "The liberal arts—rhetoric, literature, and moral philosophy—were emphasized over speculative knowledge so that they would acquire the ethical and political virtues that would enable them to counsel their monarch" (Immel). ¶ Intended more for the teacher than the student, Ascham divided his book into two broad sections. The first, on "the bringing up of youth," explores the qualities of a good scholar and teacher, giving the work some flavor of a conduct book (enhanced by his moralizing tone). The second half, on "the ready way to the Latin toong," covers the imitation of classical writers and explains his method of double translation. Ascham popularized the latter, wherein a student would translate from Latin to English, then from English back into Latin, thereby reducing the potential for mistakes introduced by schoolmasters. ¶ The book may never have seen the light of day without his widow, Margaret, who prepared her late husband's manuscript for publication and raised the funds to see it happen. "It was unusual for a woman in the 16th century to allow her name to appear in print. We can only speculate about Ascham's feelings as she did so: pride in having brought a most appealing book out of obscurity, perhaps, and a desire for recognition of the efforts she had made" (Hager). ESTC gives Margaret an editor credit, but other sources indicate she made no textual revisions.

PROVENANCE: A single early Latin annotation on p. 3, and A.387 inked at foot of title in an early hand.

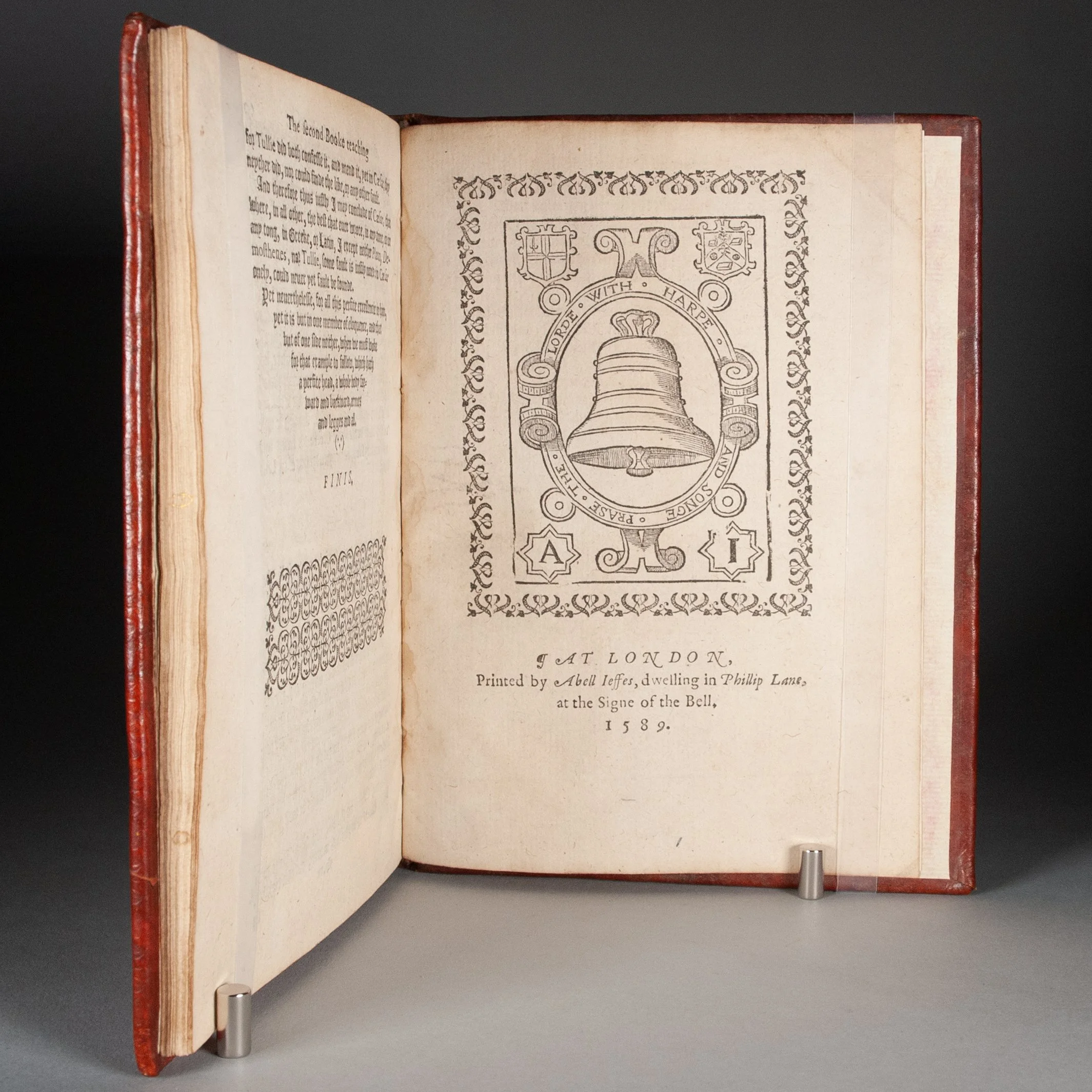

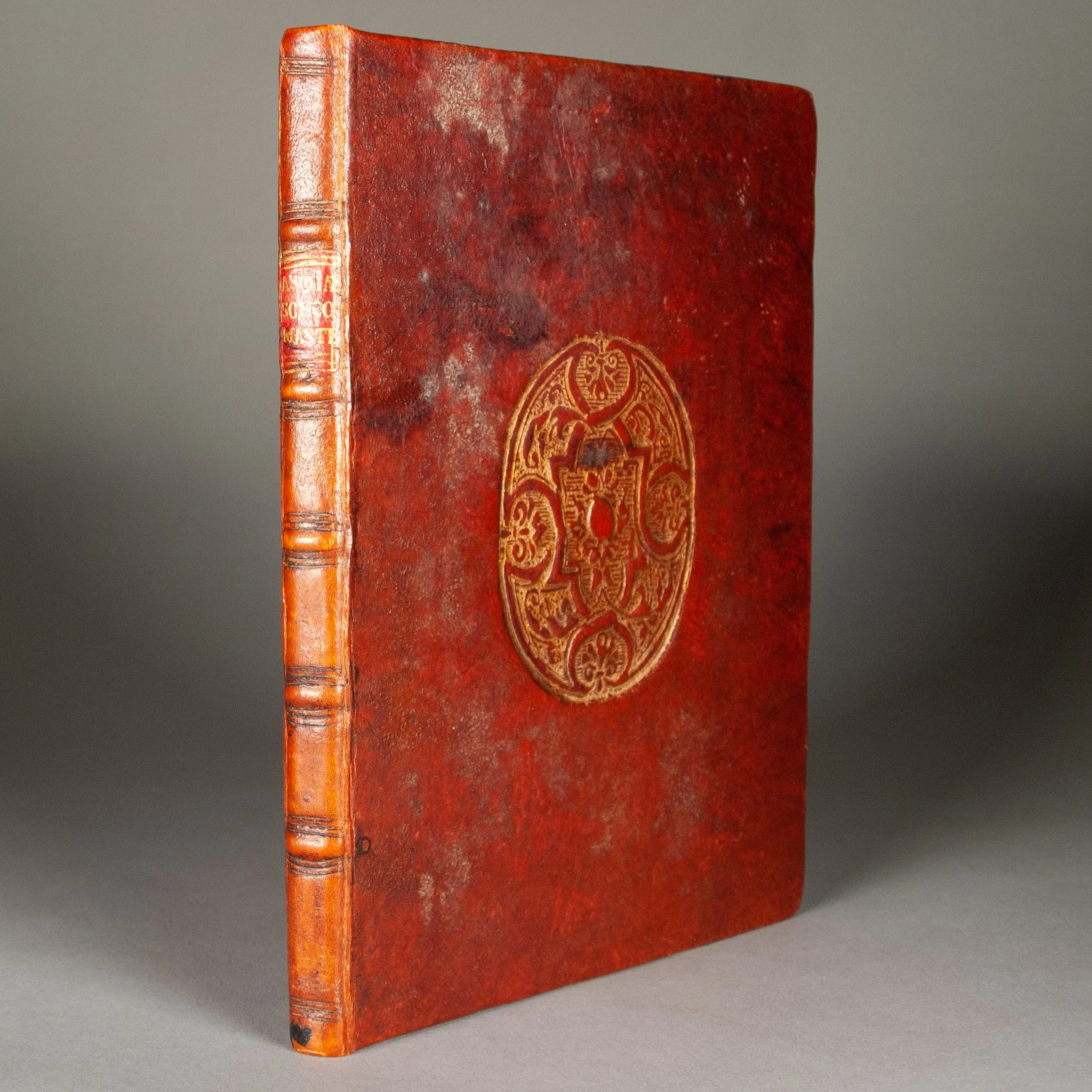

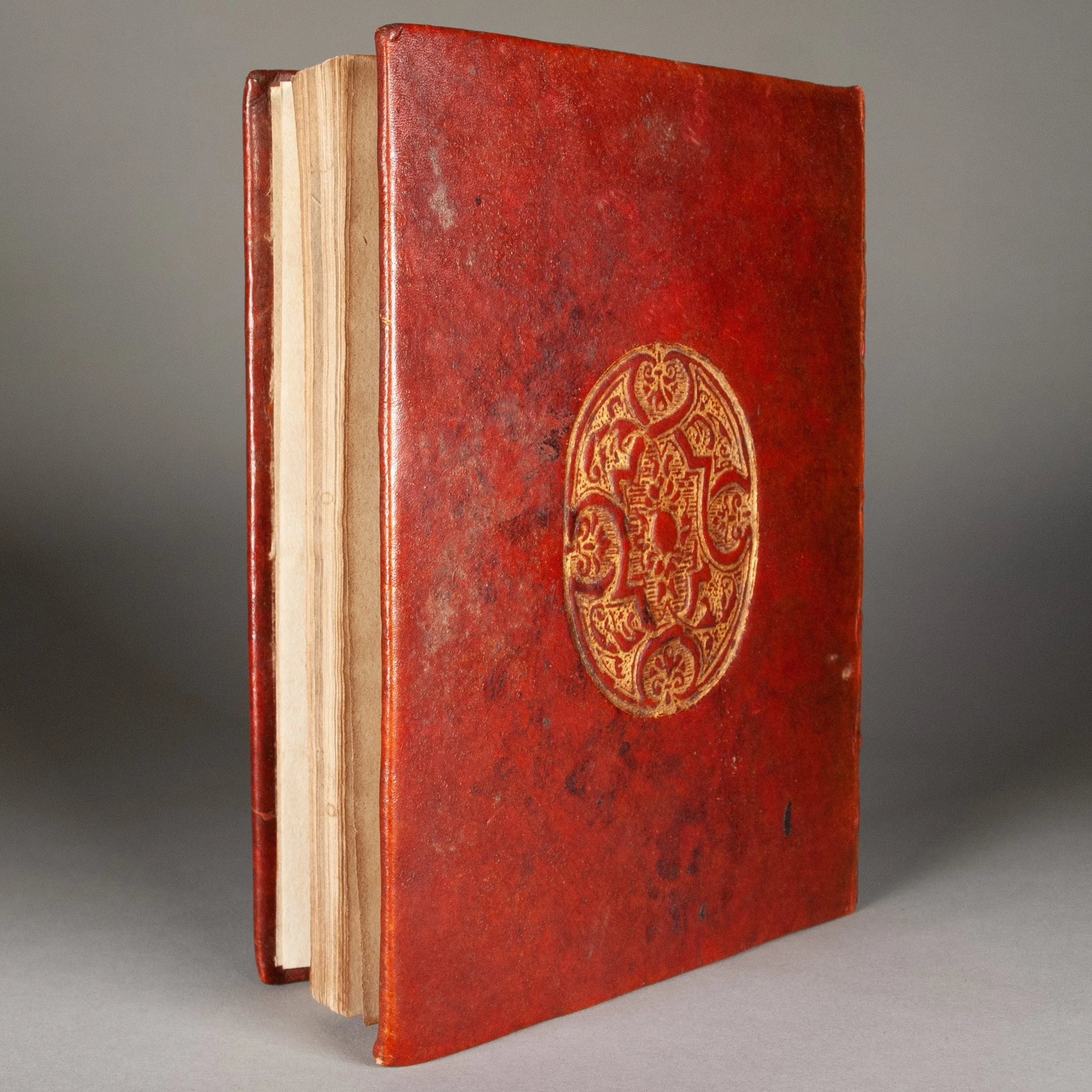

CONDITION: Bound in much later reddish-brown leather (ca. 1900?) each cover with a typical English gilt centerpiece in period style, and the spine perhaps preserving an 18th-century title label. Woodcut printer's device above the colophon on the final leaf recto. ¶ The title dark and dusty; light dampstain on the verso of fol. 27, and a dark stain on fol. 44r, not quite 2 cm long. Leather soiled here and there, but a strong binding in decent period style.

REFERENCES: ESTC S100267 ¶ Philip Sidney (Robert Maslen, ed.), An apology for poetry (2002), p. 55 (cited above); Rosemary O'Day, "Ascham, Roger," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004), accessed online (cited above); J.B. Trapp, "Ascham, Roger," The Oxford Companion to British History (2015), accessed online (cited above); Andrea Immel, "Ascham, Roger," The Oxford Encyclopedia of Children's Literature (2006), accessed online (cited above; "His decision to write The Schoolmaster in English instead of Latin brought humanistic educational theory and methods to a wider audience"); Jennifer Richards, "Ascham, Richard," The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature (2006), accessed online ("Its influence on English fiction has been significant"; excellent bio and summary of The Schoolmaster); Alan Hager, Encyclopedia of British Writers: 16th, 17th, and 18th Centuries (2005), p. 7 (cited above); The Encyclopedia of English Renaissance Literature (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), v. 1, p. 16 ("The scholemaster is regarded as a key work of Tudor pedagogy, providing valuable commentary on the educational fashioning of youth and the relationship between schoolmaster and pupil...The scholemaster also made an important contribution to the now arcane sixteenth-century debate over whether English poetry should adopt rhyme or be modelled on classical, quantified metre"); The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance (2005), accessed online ("an important influence on Sidney's Defence of Poetry"); "Ascham, Roger," The Oxford Companion to English Literature (2009), accessed online ("an important landmark in Renaissance educational theory"); Madeleine B. Stern and Leona Rostenberg, Books Have Their Fates (2001), p. 91-92 ("After the author's death it was Margaret Ascham who published the book just as her husband left it, adding only a dedication to the chancellor of Cambridge University. In refraining from editorial revisions, she demonstrated the acumen of the truly wise. Margaret Ascham knew how to let learning speak for itself.")

Item #931