Foundational rhetoric in contemporary binding

Foundational rhetoric in contemporary binding

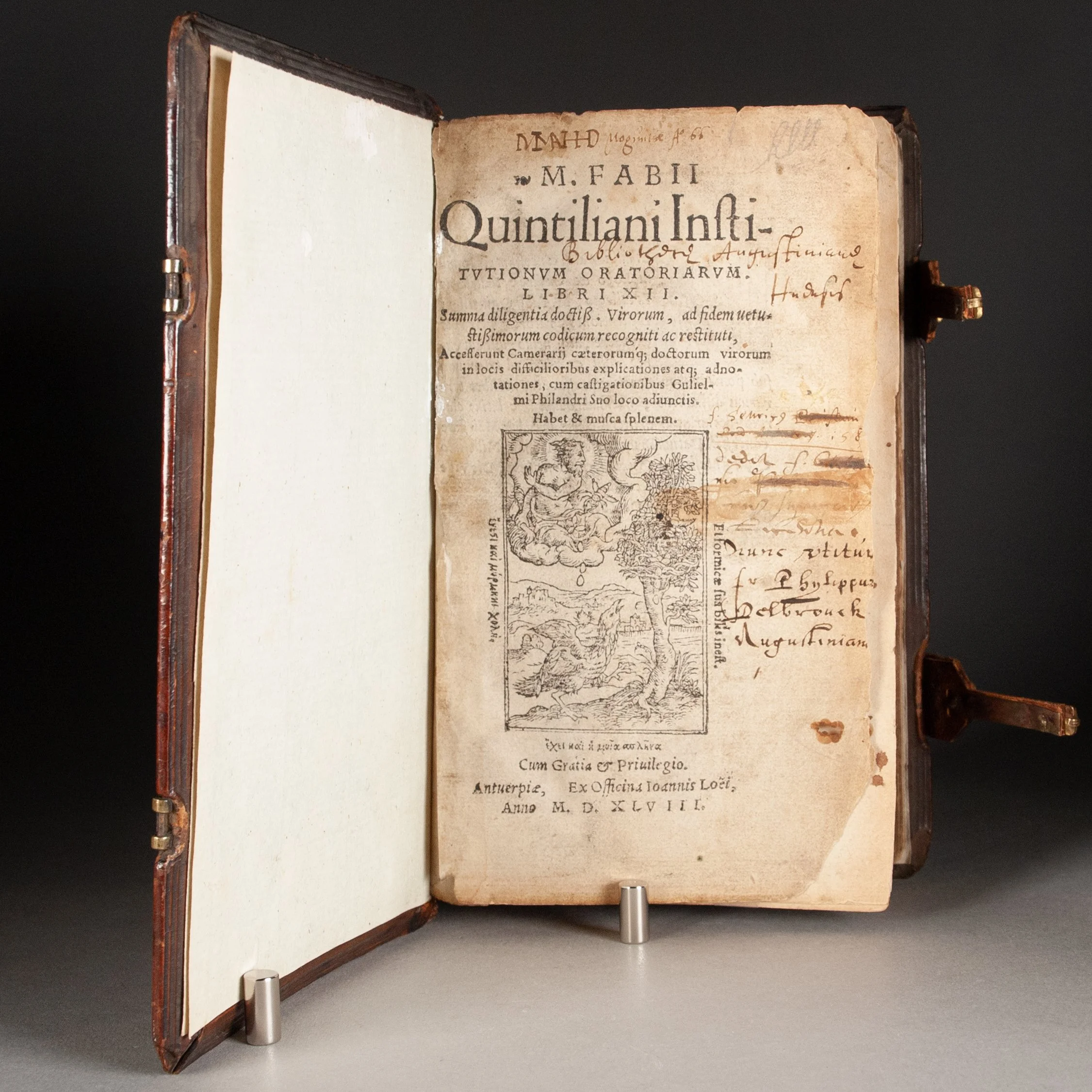

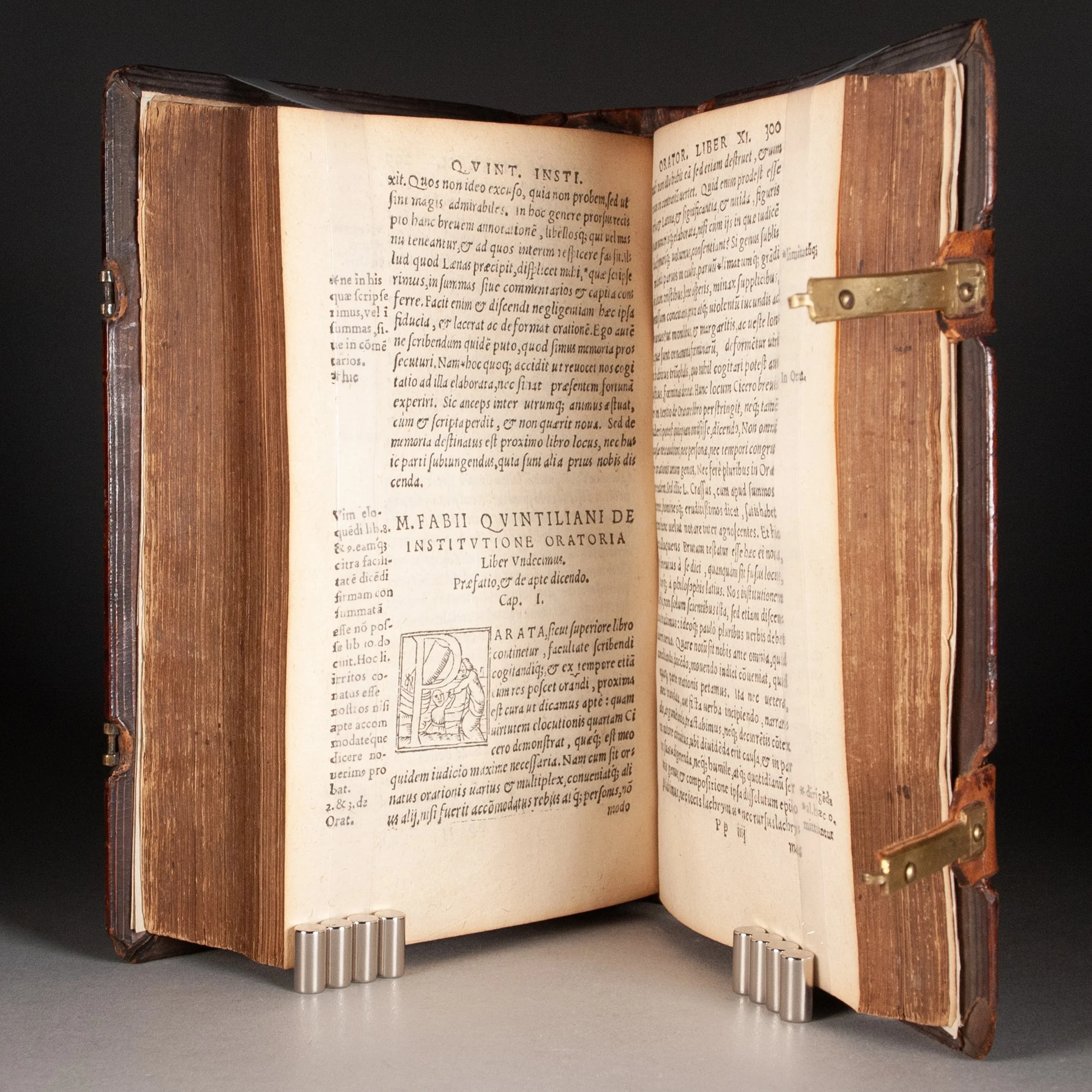

Institutionum oratoriarum libri XII, summa diligentia doctiss. virorum, ad fidem vetustissimorum codicum recogniti ac restituti; accesserunt Camerarii caeterorumq[ue] doctorum virorum in locis difficilioribus explicationes atq[ue] adnotationes, cum castigationibus Gulielmi Philandri suo loco adjunctis

by Quintilian | with notes by Joachim Camerarius | edited by Guillaume Philandrier | and contributions from Gilbert de Longueil

Antwerp: Jan van der Loe, 1548

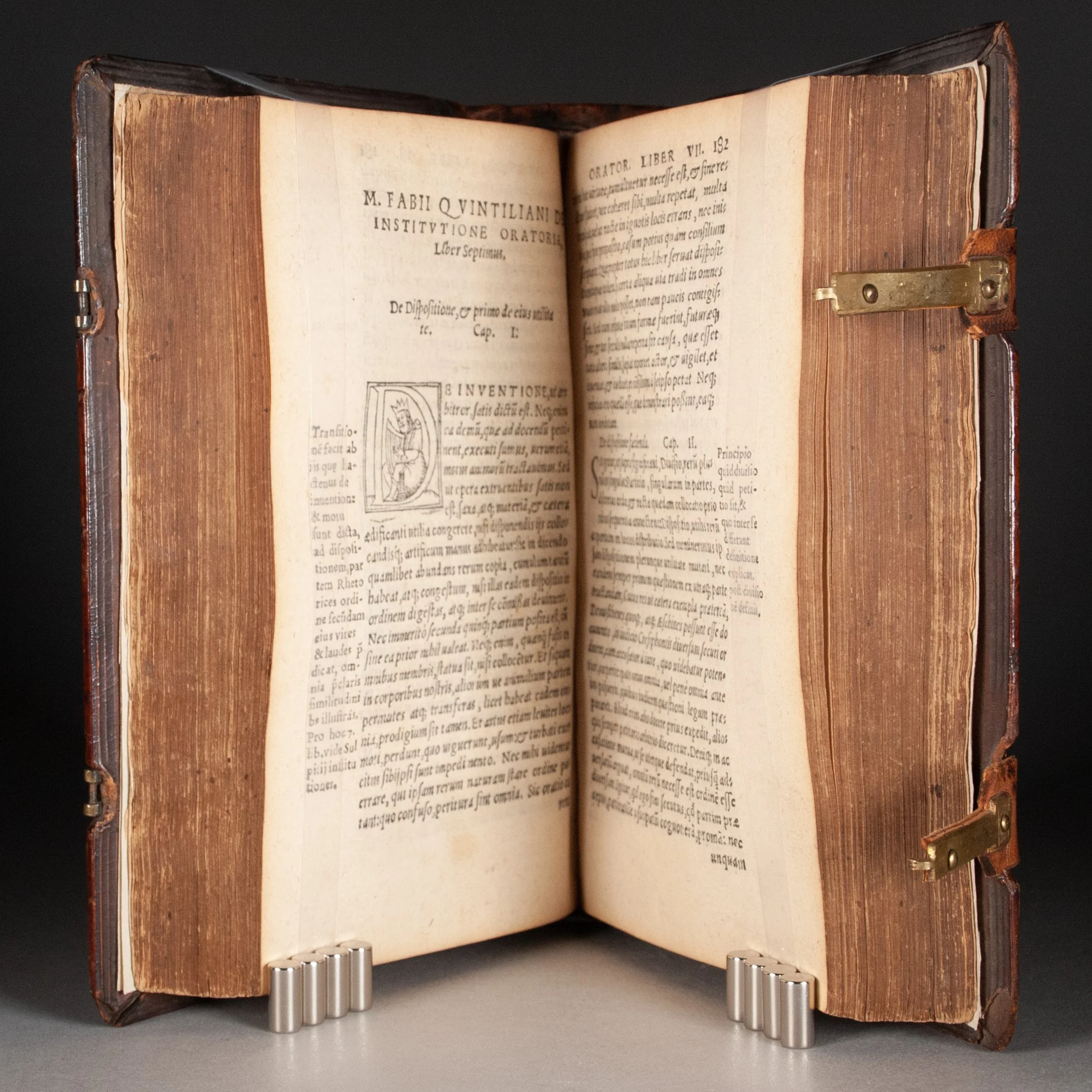

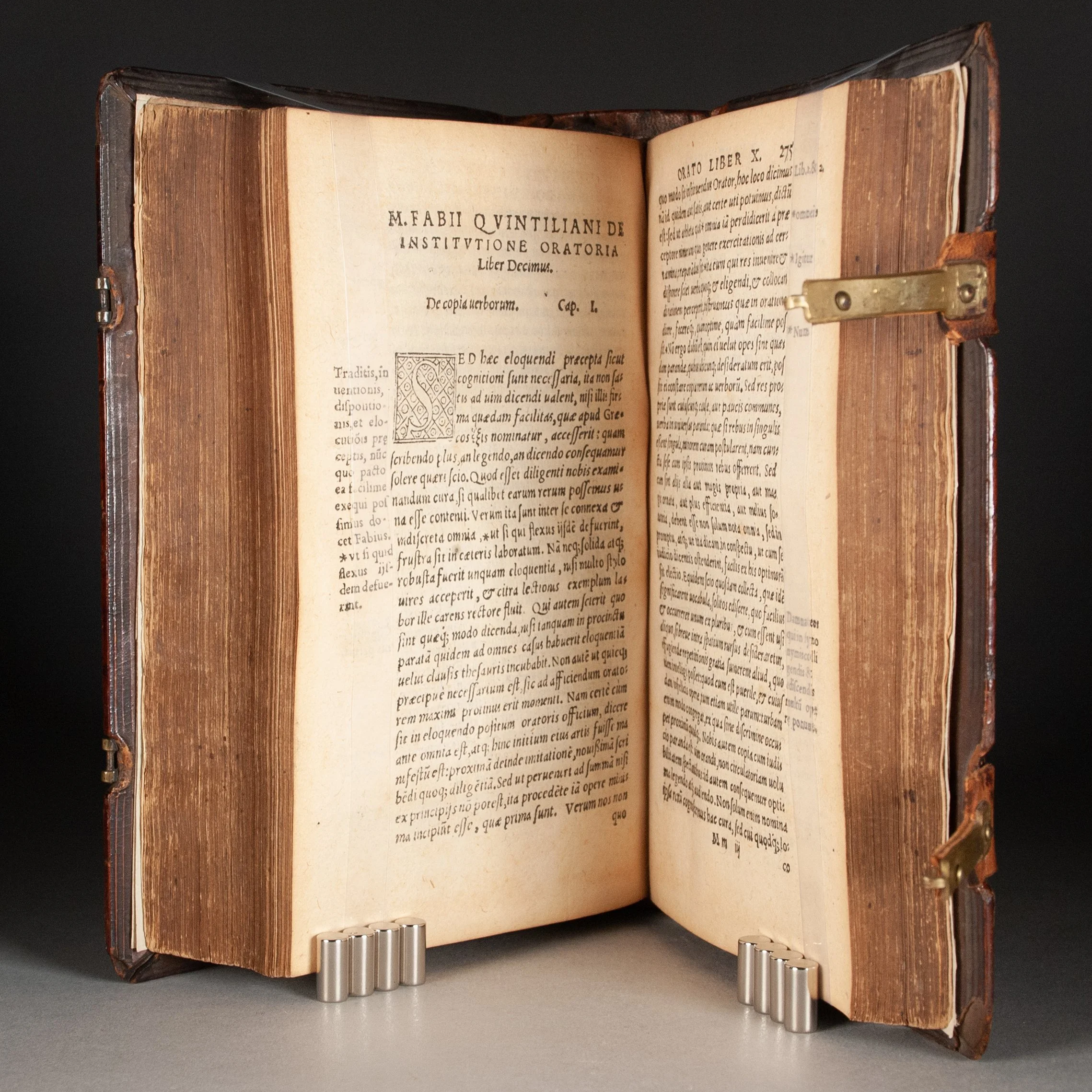

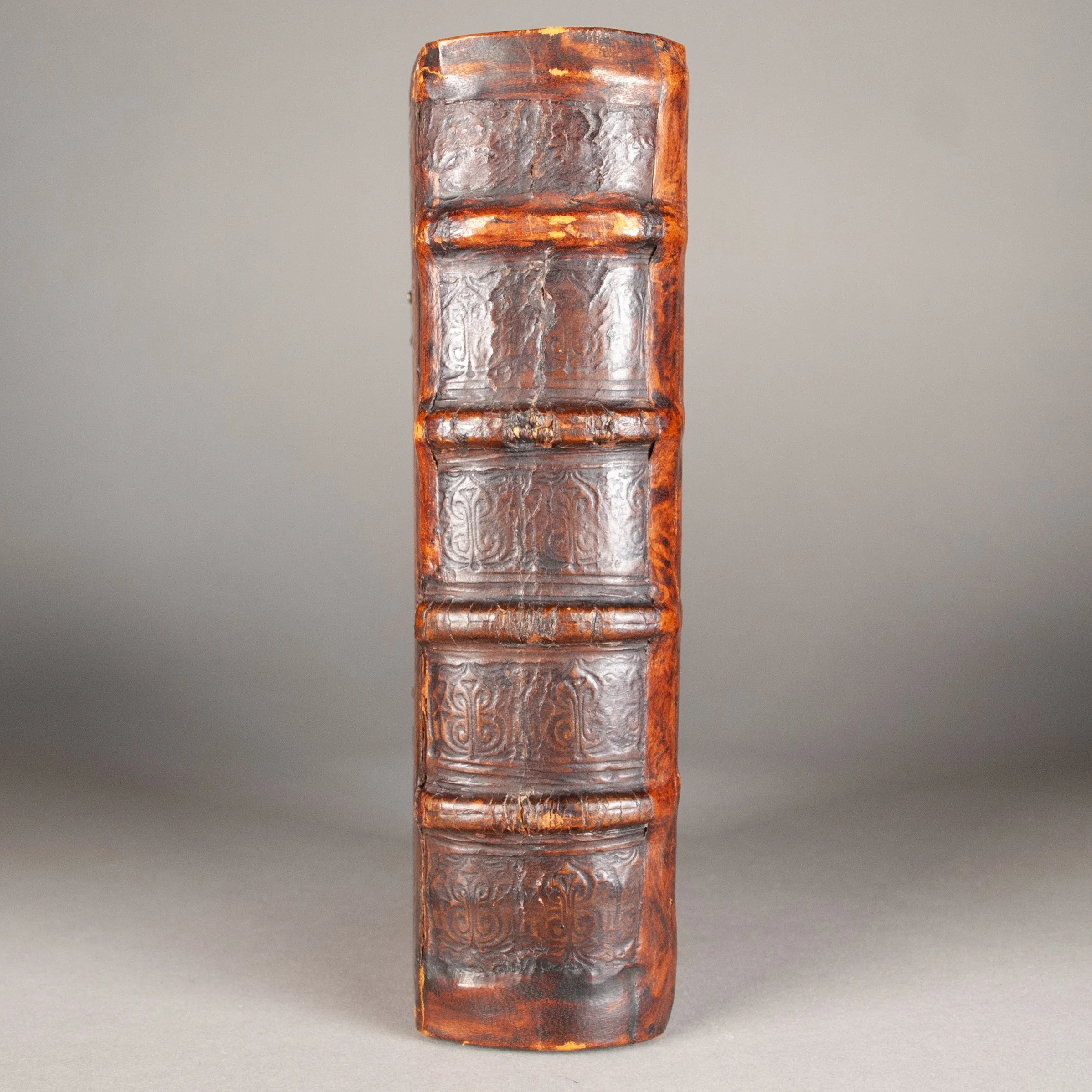

[4], 359, [52] leaves | 8vo | *4 A-3E^8 3F^4(-3F4 blank) | 178 x 103 mm

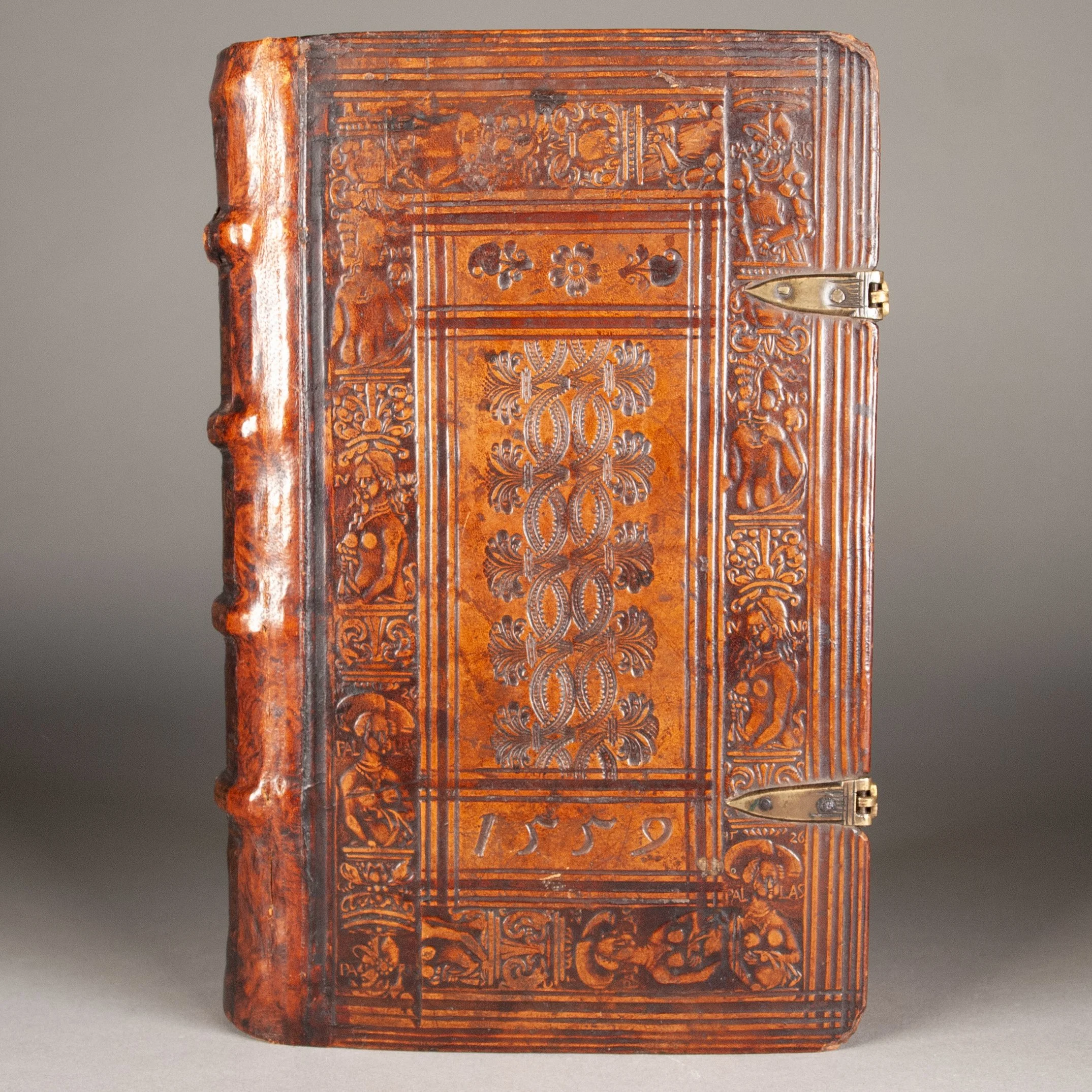

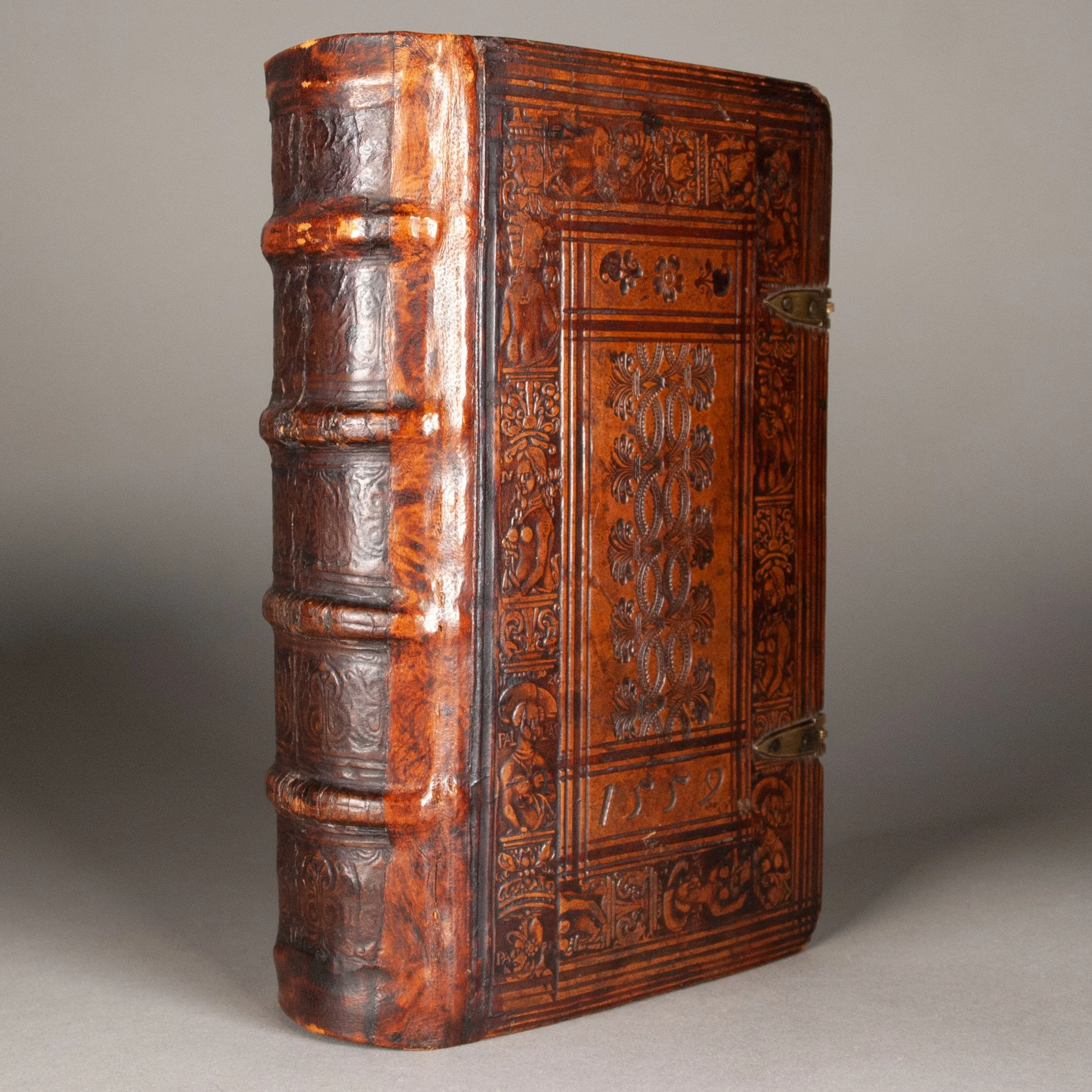

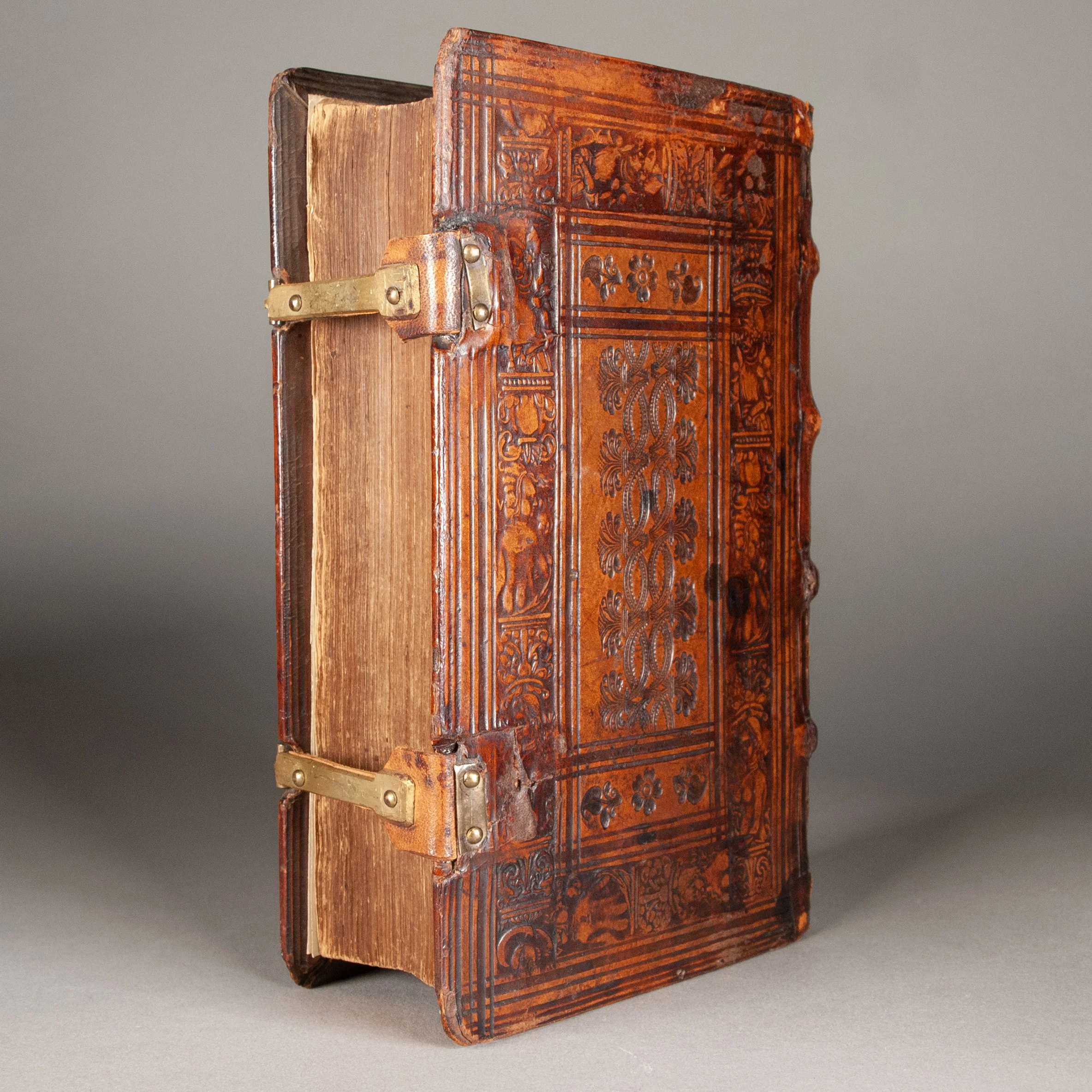

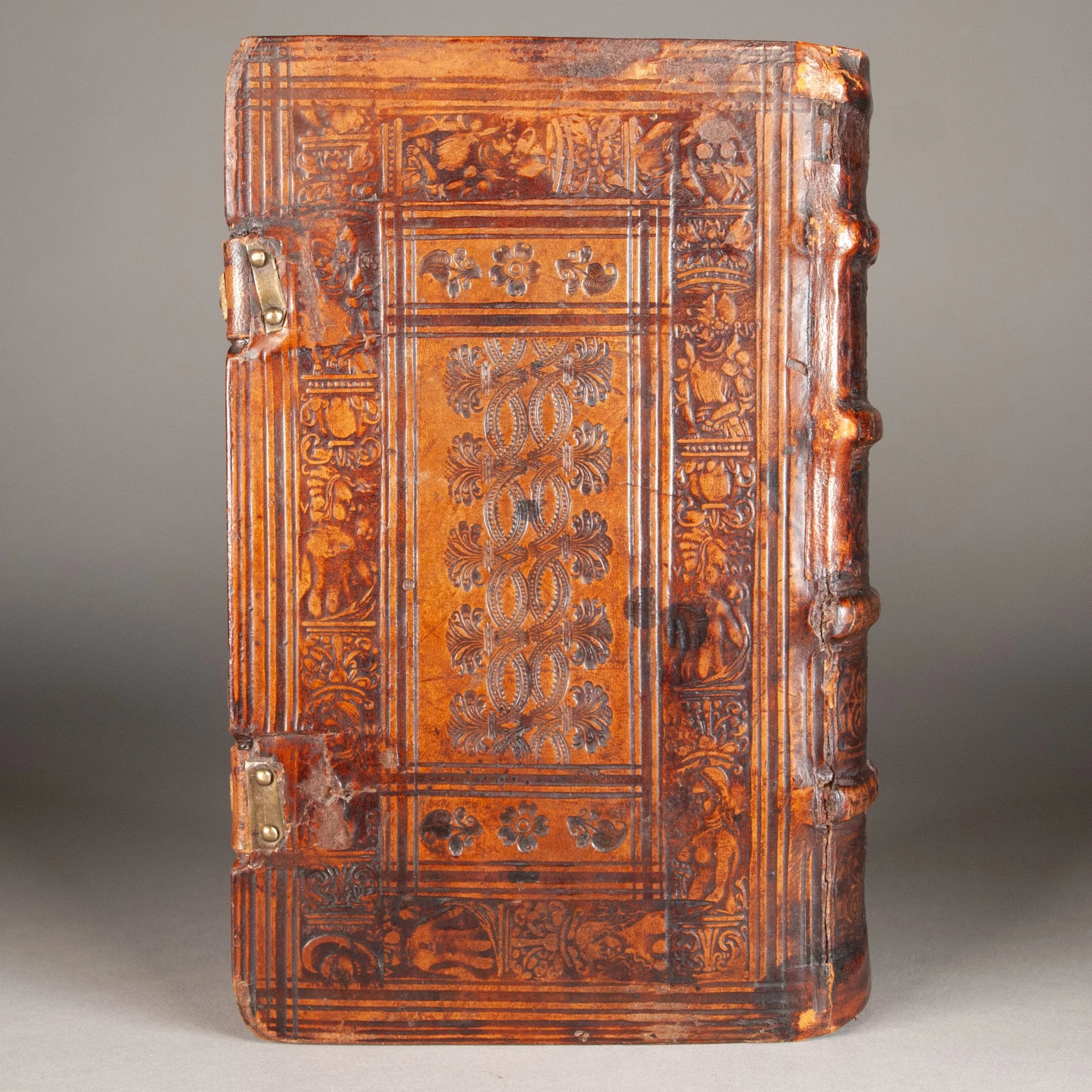

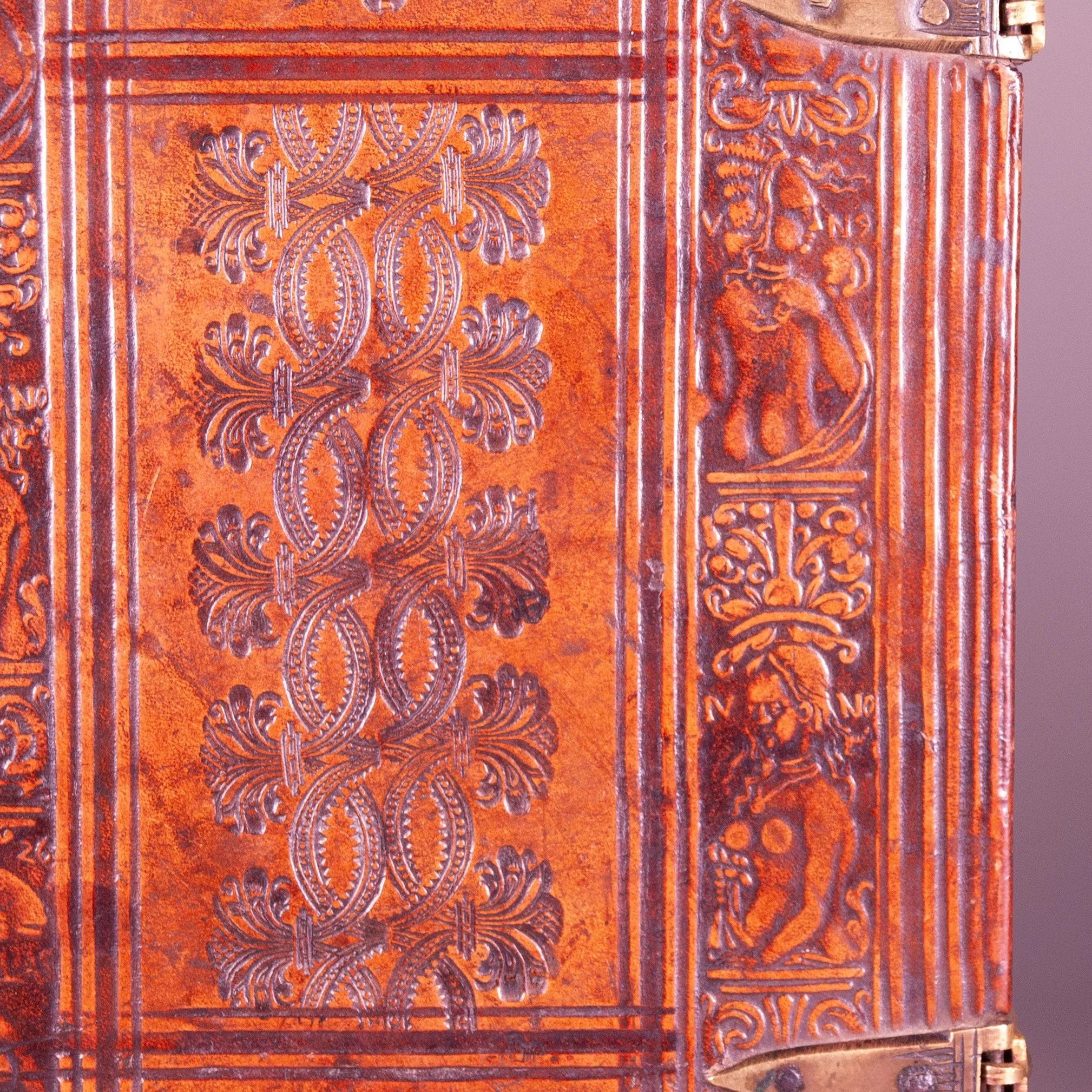

An expertly prepared edition of this standard rhetoric manual, a bedrock humanist work, “highly influential throughout the Renaissance” (Manguel), and “a foundational text for Renaissance readers, writers, and speakers” (Sherman). Given its status, it's no wonder it attracted the commentary of one of Germany's most esteemed scholars; Camerarius's notes on Quintilian were in print as early as 1527. Philandrier's edition first appeared in 1531, and Longueil's contributions in 1534. ¶ Long available only in partial form, Quintilian's complete text was among the many discoveries made by famed manuscript hunter Poggio Bracciolini. The revelation in 1416 "provided strong ancient support for a new education combining eloquence and moral philosophy for the civic life"—for the very foundation of humanism. "Quintilian became the revered authority behind every humanistic pedagogical treatise through the next century and a half. Quintilian supplied a synthesis of pedagogical practice and rationale which the humanists used to explain and justify their rejection of medieval rhetoric specifically and medieval education generally" (Grendler). Rhetoric was indeed vital to humanists, to the educated broadly, “the art of arts and science of sciences,” as Anthony Grafton puts it. On a fundamental level, it was (and remains) power and influence—the ability to persuade others. "The humanists of the sixteenth century believed that as rhetoric had been a civilizing instrument in the past, so it could solve the problems of conflicting interests, disorder, and endemic violence that now plagued the urban community" (Chrisman). ¶ Here Quintilian advocated the loci method of memory retention, popularized much later as the mind palace of Sherlock Holmes; he was perhaps the first to divide a student body into different classes, a concept rediscovered in the 16th century and which underpins pedagogical structure even today; and he was apparently the first Roman to suggest rewarding the best students with prizes, a practice that became commonplace in early modern European education. ¶ Not to downplay Quintilian's importance, but we're rather taken by this gratifying contemporary binding, tooled in part with a rather explicit Judgment of Paris roll dated 1526. Paris was tasked with judging the fairest woman: Hera (here Juno), Athena (Pallas), or Aphrodite (Venus). Aphrodite bribed him with Helen of Sparta, thence the Trojan War. The binding itself is dated 1559, the central panel of each cover decorated with a palmette roll. The palmette roll was relatively common in the 16th century, perhaps even more so in the 17th, and appears typically to have been used as an outer border. We do find limited evidence of palmette rolls used as here, within a central panel, and we can't help but notice a certain stylistic echo of the popular acorn binding—namely in the central vertical arrangement of crescents.

PROVENANCE: With a number of early ownership inscriptions on the title page, perhaps suggesting Augustinian provenance in Belgium. For example, we note the signature of one Phylippus Delbrouck Augustinian[us?].

CONDITION: Contemporary blind-tooled polished brown calf over wooden boards, as described above. Without the final blank leaf. ¶ Title leaf rather crudely remargined, obscuring a little text on its verso; some marginal loss along fore-edge of title, just barely touching some ownership inscriptions; small marginal tear in B5, not affecting text. Likely recased, endpapers replaced, and sympathetic brass clasps added (using original catchplates); joints and spine ends repaired, with cracking still visible along half the rare joint, though the whole book remains firmly intact; corners bumped, and a hint of repair along the upper edge of the rear board.

REFERENCES: USTC 404135; STCV c:stcv:12926736 ¶ On Quintilian: Paul F. Grendler, Schooling in Renaissance Italy (1989), p. 120 (cited above); Willaim H. Sherman, Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England (UPenn, 2008), p. 49 (cited above); Alberto Manguel, A History of Reading (1997), p. 72 (cited above); Christian Coppens, Leuven in Books, Books in Leuven (1999), p. 224 (“Memory being closely related to rhetoric and discourse, it was essential to establish places in the memory where texts could be stored inside a structure which gave support to the memory and helped it to find things. A house with many rooms was the ideal residence for the loci. Quintilian, who was much read in the sixteenth century, taught this.”), 244 (on prizes and classes); Jan M. Ziolkowski, "Middle Ages," A Companion to the Classical Tradition (2007), p. 17 ("in scholastic parlance the noun classis had been used to denote a class of pupils at the latest since Quintilian") ¶ On rhetoric: Anthony Grafton, Bring Out Your Dead: The Past as Revelation (Harvard, 2001), p. 168 (cited above); Miriam Usher Chrisman, Lay Culture, Learned Culture (1982), p. 196 (cited above; rhetoric "encompassed much more than the ability to speak well. Rhetoric, in the minds of the Classical humanists, was the noblest of the human arts, the attribute which distinguished men from animals. Through the gift of speech, men had learned to guide and control society."); Carlos Eire, Reformations (2016), p. 69 (“Rhetorical skills were highly prized by humanists, not for their own sake, but for the power eloquence can have in moving people to action”); Peter Bayley, French Pulpit Oratory 1598-1650 (1980), p. 23 (“nothing in the educational theory or practice of the time leads us to think that rhetoric was considered as anything other than essential and serious”); Michel de Montaigne, "Of the Vanity of Words," Complete Essays (1976), p. 222 (rhetoric: "It is an instrument invented to manipulate and agitate a crowd and a disorderly populace, and an instrument that is employed only in sick states, like medicine ¶ On the binding: Eric Speeckaert, Quatre siecles de reliure en Belgique (1989-1998), v. 1 #27-#29, v. 2 #34 #36, v. 3 #29 #30 #32 #34 (all 17c examples of palmette rolls used as outer borders; no 16c or central panel uses illustrated); Fine and Historic Bookbindings from the Folger Shakespeare Library (1992), p. 80 (a binding of ca. 1560, perhaps Swiss, which pairs similar central rolls—interlocking crescents, but no palmettes—with a figurative outer border); E.Ph. Goldschmidt, Gothic & Renaissance Bookbindings (1928), v. 2, plate XLIX (a standard acorn panel binding, for comparison)

Item #690