Book of secrets, unrecorded edition, annotated

Book of secrets, unrecorded edition, annotated

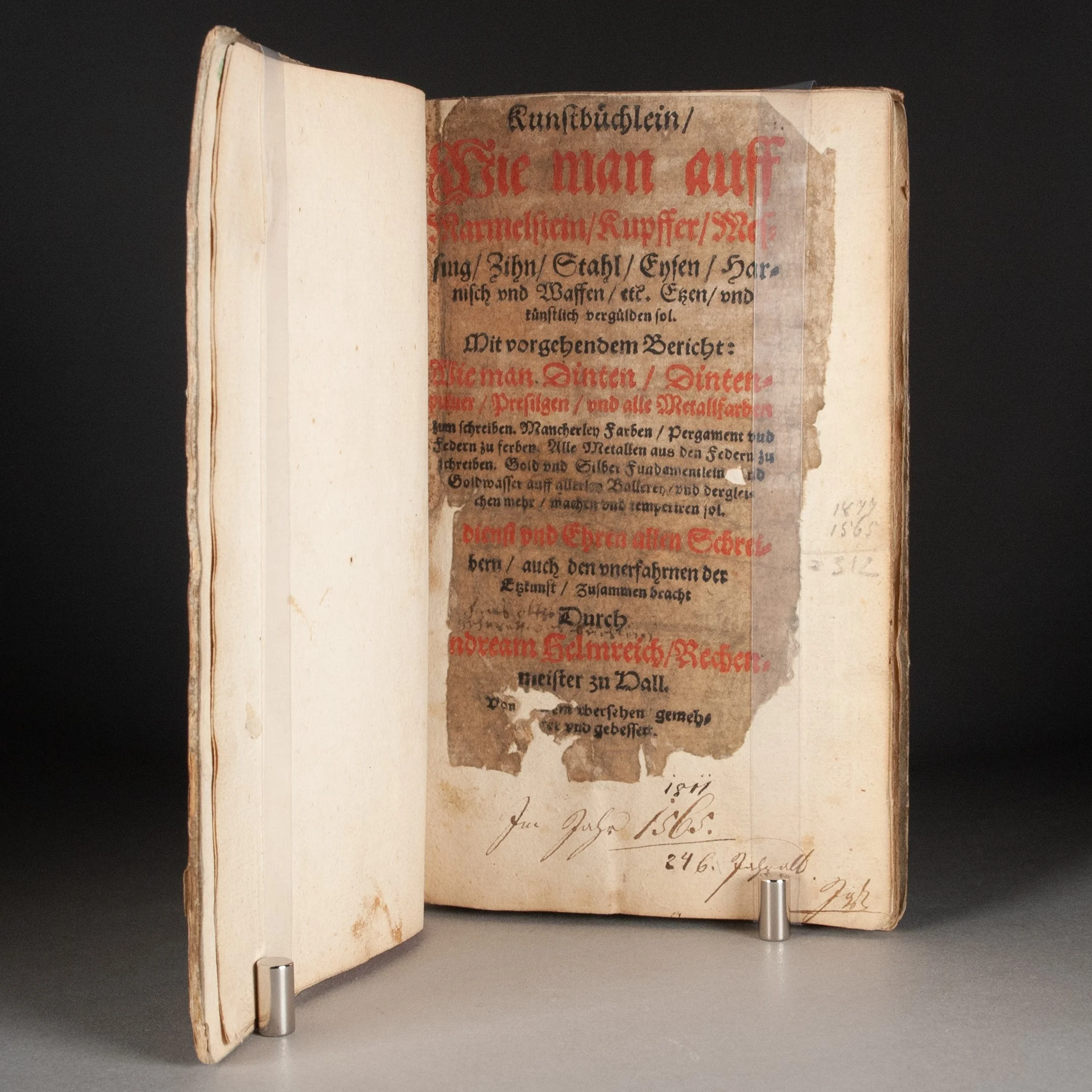

Kunstbüchlein, wie man auff Marmelstein, Kupffer, Messing, Zihn, Stahl, Eysen, Harnisch und Waffen, etc. Etzen und künstlich vergülden sol; mit vorgehendem Bericht: wie man Dinten, Dintenpulver, Presilgen, und alle Metallfarben zum schreiben, mancherley Farben, Pergament und federn zu ferben, alla Metallen aus den federn zu schreiben, gold und silber fundamentlein und Goldwasser auff allerley Ballerey, und dergleichen mehr, machen und temperiren sol; dienst und ehren allen schreibern, auch den unerfahrnen der Etzkunst, zusammen bracht...von [new?]em ubersehen gemehret und gebessert

by Andreas Helmreich

[Basel: Johann Schröter, ca. 1598]

[80] p. + [16] p. added ms | 8vo | A-E^8 | 165 x 100 mm

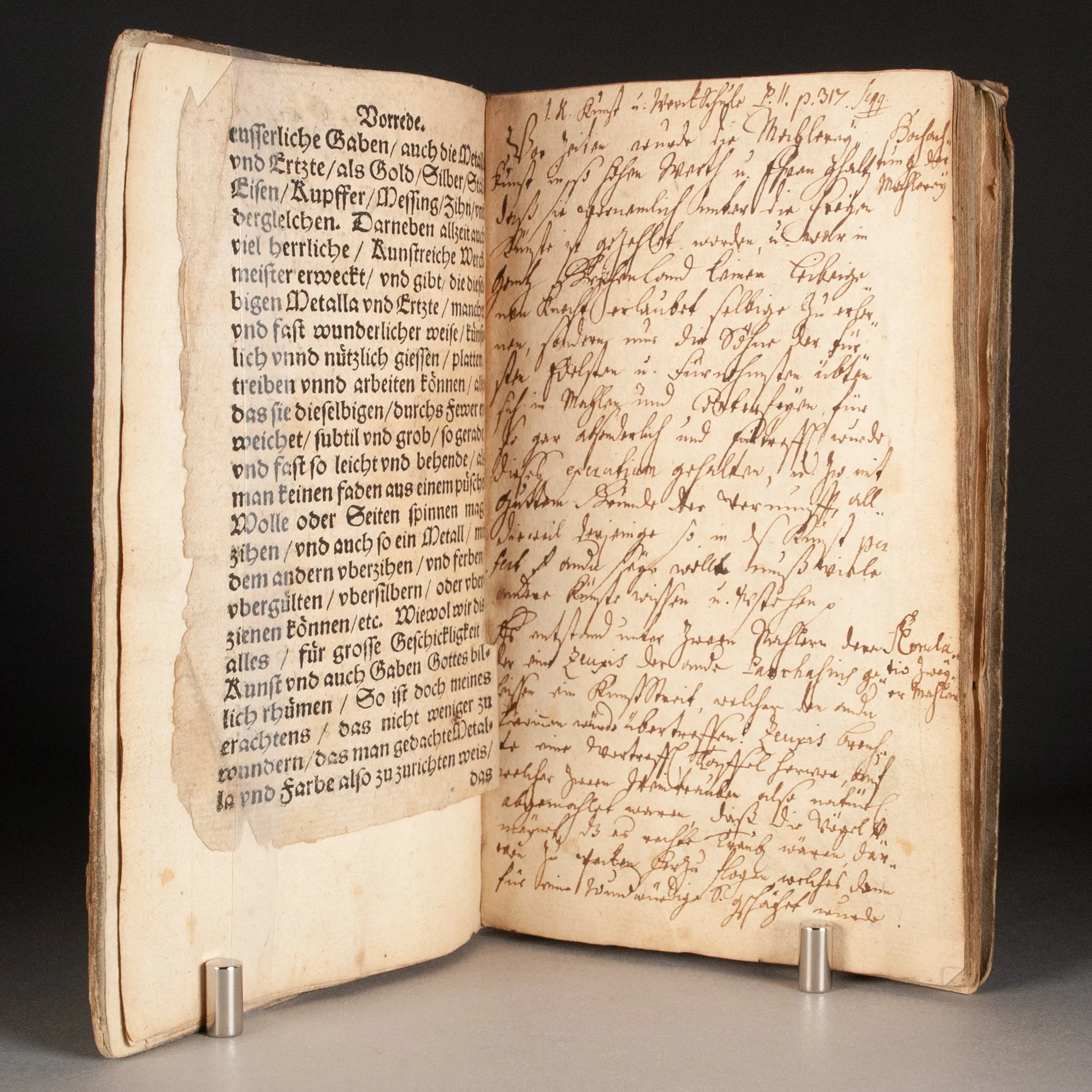

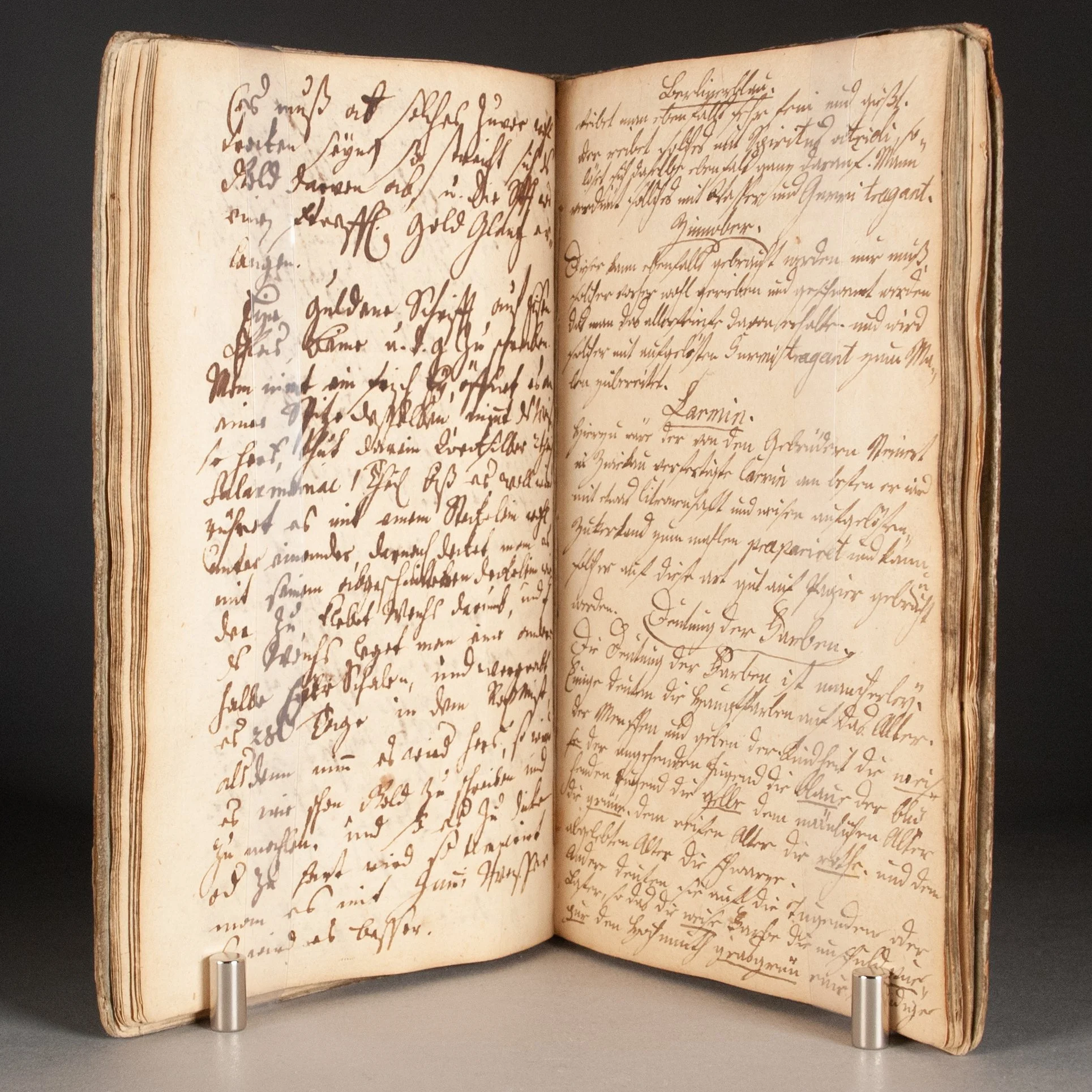

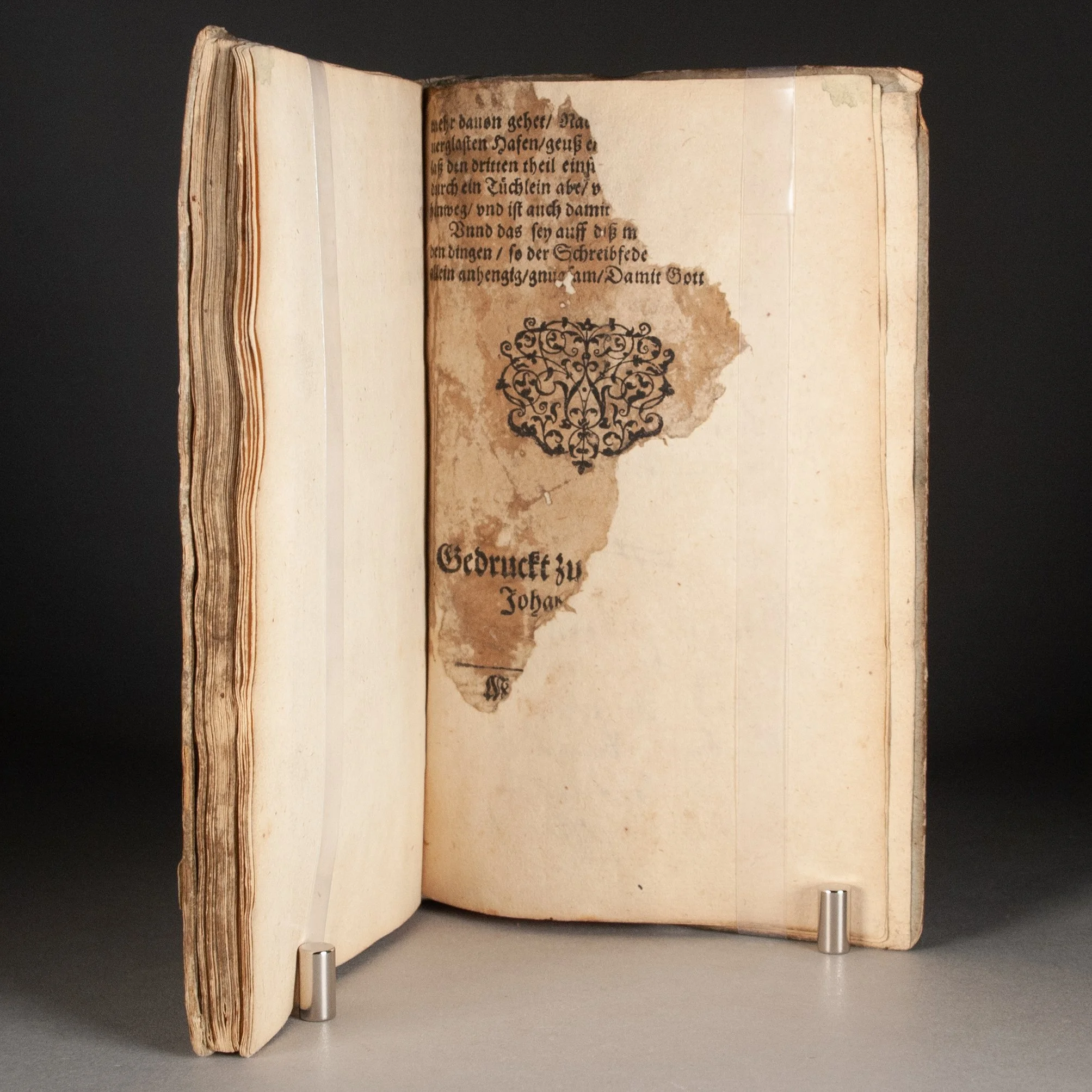

By all appearances an unrecorded edition of the German mathematician's popular book of secrets, and one with instructions of particular interest to scribes. The work was in print by 1567 and appeared regularly over the course of the next century. Our source presumed this to have been printed in Basel by Johann Schröter, though on what grounds was not clear. We followed the lead, and sure enough found the same arabesque ornament at the end of our book used similarly in a 1598 Schröter imprint (he used these types widely, too). We think the ornament was in slightly better shape for our book, and so ours was perhaps printed earlier—note that its bottom element may be damaged in the 1598 book—though we allow for the vagaries of presswork. ¶ The seductively named book of secrets was a ubiquitous genre, and they easily rank "among the most widely read works of the medieval and Renaissance periods" (Eamon, "Books of Secrets"). Its 16th-century heyday likely has its roots in the enduring popularity of the medieval Secretum Secretorum, originally a pseudo-Aristotelian letter sent to Alexander the Great. Over the centuries, it evolved and expanded to become a kind of revered encyclopedia, containing the kind of "secrets" redolent of its 16th-century successors. This next generation first took off in Italy in the 1520s. "In Germany, a group of popular craft manuals, known as the Kunstbüchlein, appeared in the 1530s and were frequently reprinted and translated throughout the sixteenth century. These handbooks, which offered recipes on dyeing, pigment-making, metallurgy and practical chemistry, were printers' compilations from workshop notes, but were presented to the public as efforts to improve the arts through scientific techniques" (Eamon, "Secrets of Nature"). It blended the scientific and the technical, and became part of the fast growing corpus of how-to literature. "To some extent they served as mediators between elite and popular culture," as "the authors of these works were not among the leading intellectuals of the day but came rather from the ranks of a 'middle-level' intelligentsia composed of professional writers, physicians, and nonacademics who wrote specifically for that market" (Eamon, "Science and Popular"). But you'll find no secret to the sorcerer's stone here. "What they typically revealed was only recipes, formulae, and 'experiments,' often of a fairly conventional sort, associated with one of the crafts, the household and garden, or medicine...In other words, books of secrets were technical 'how-to' books rather than works of theoretical science, and the information they contained was secret only in the sense that it was likely to have been the property of specialized craftsmen who normally communicated their knowledge orally rather than in writing; or the recipes were the discoveries and inventions of experimenters who refused to publish them out of fear of having them cheapened" (ibid.). ¶ True to form, Helmreich's book is chock full of useful recipes. He provides extensive instructions for making ink, including the common sort made from galls, plus inks of various colors, typically with multiple recipes for each. He explains how to make colored parchment or paper, and how to make pens. Then he approaches the topics from a more metallurgical perspective, explaining how to make ink from a variety of metals—gold, silver, brass, copper, steel, etc. He provides special instructions for using such inks on wood, and for applying gold and silver to glass and armor; he explains how to prepare white parchment for writing, how to prevent pests from eating your writing surfaces, how to prepare gold and silver grounds for writing, and how to make sealing wax. The final gathering provides instructions for etching, gilding, and silverplating various metals. ¶ Rare in any edition. We find a handful of late-17th-century copies in North American libraries, but only a 1593 edition at NYPL that likely precedes ours. We find only a single auction record, for any edition: a ca. 1600 copy, with a facsimile title page, sold in 2005.

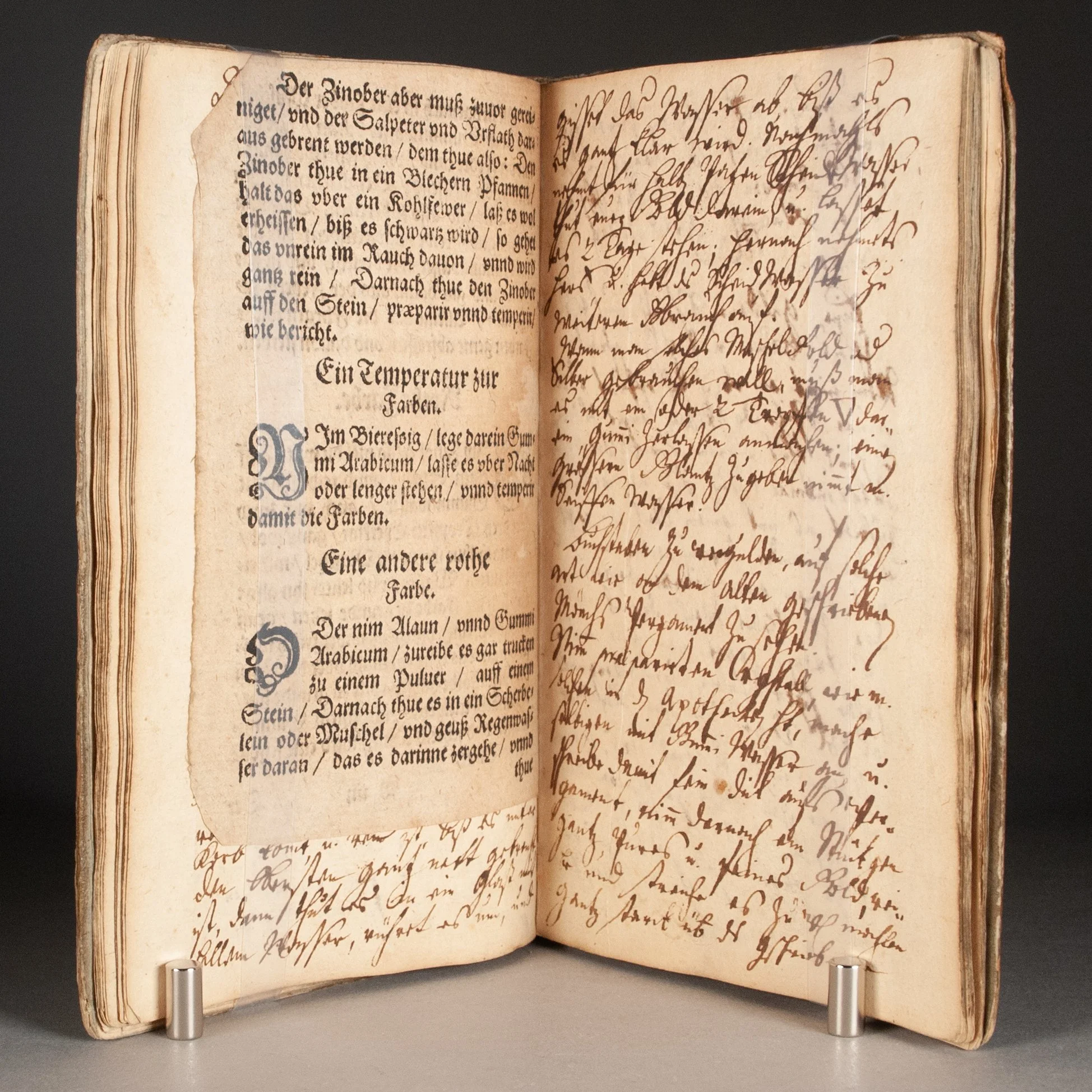

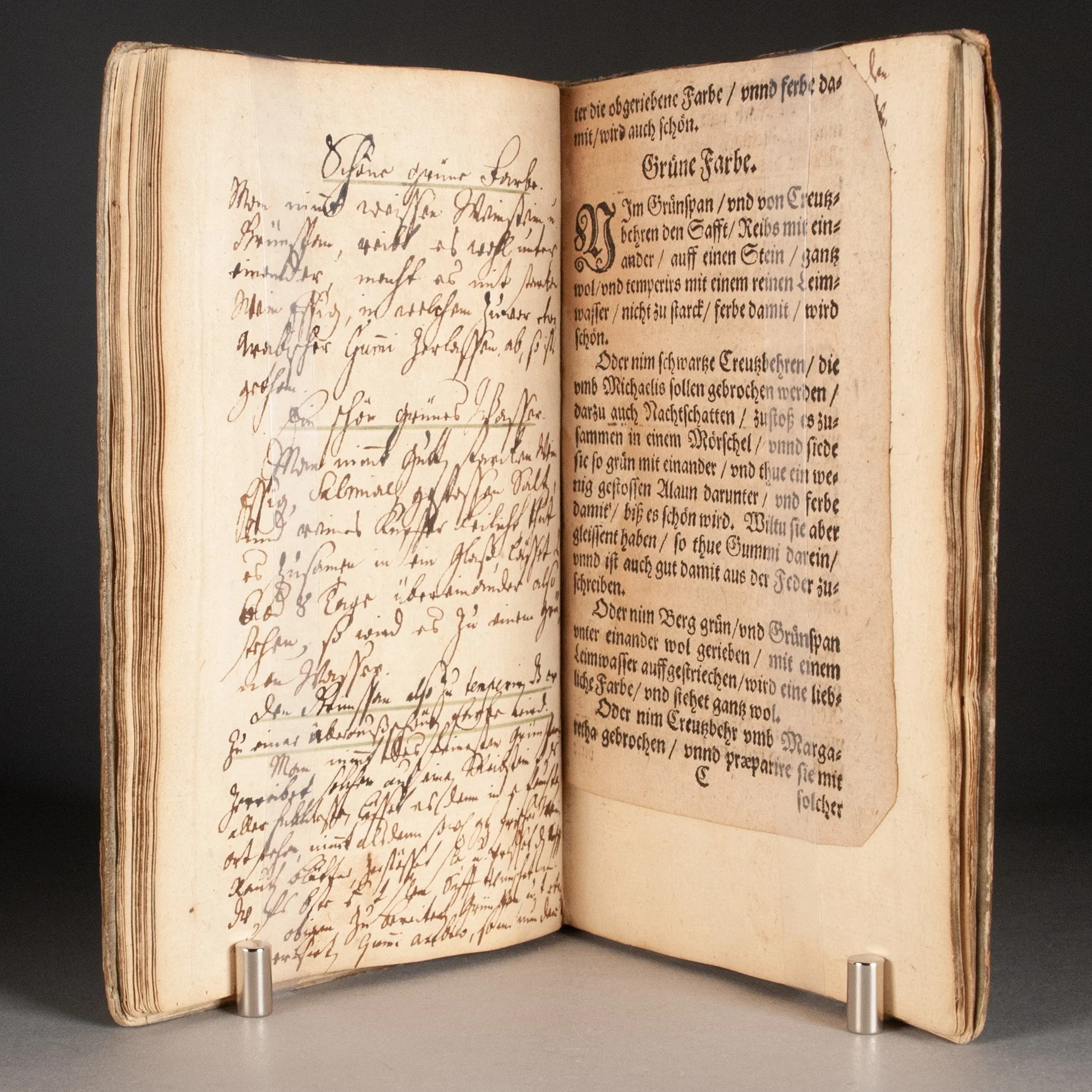

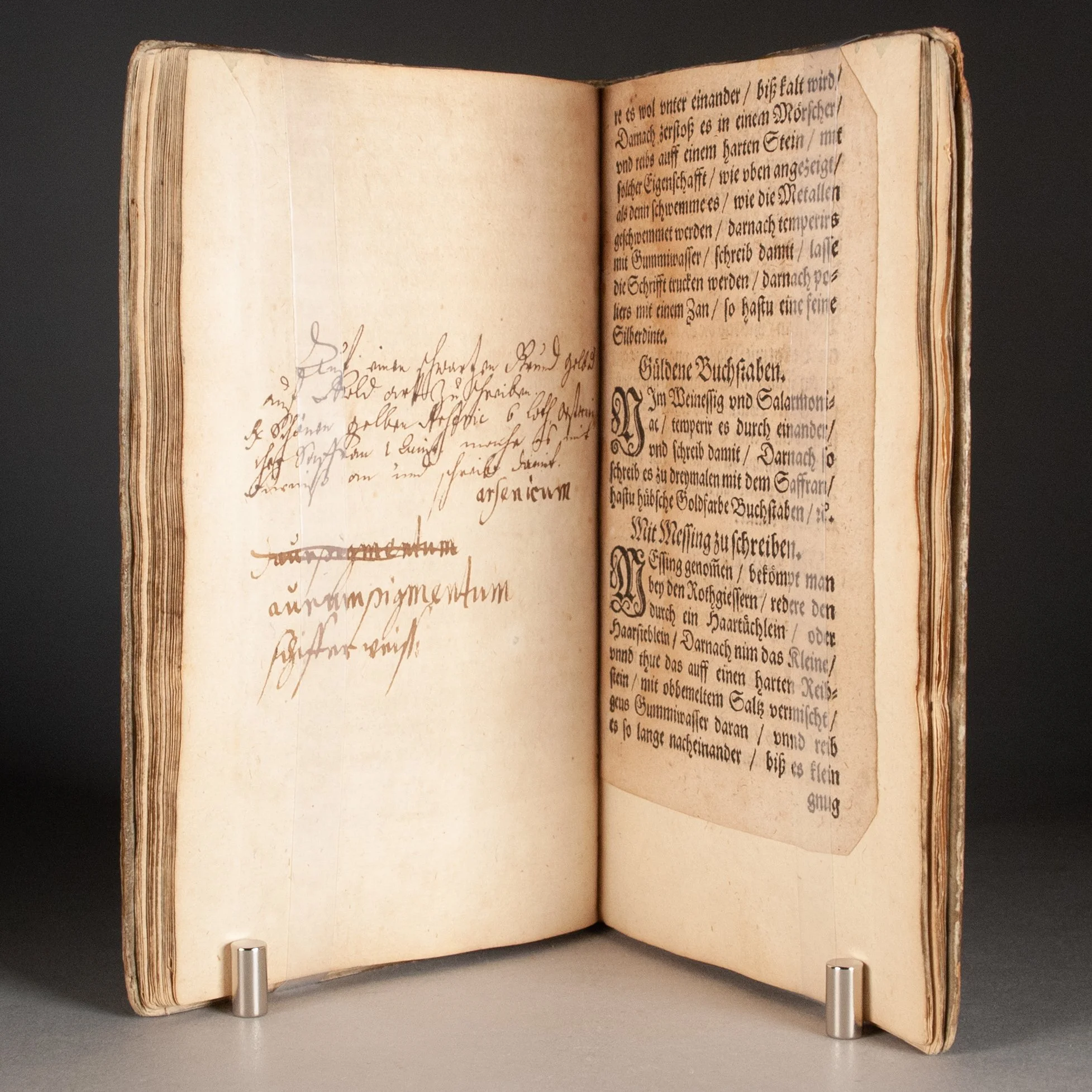

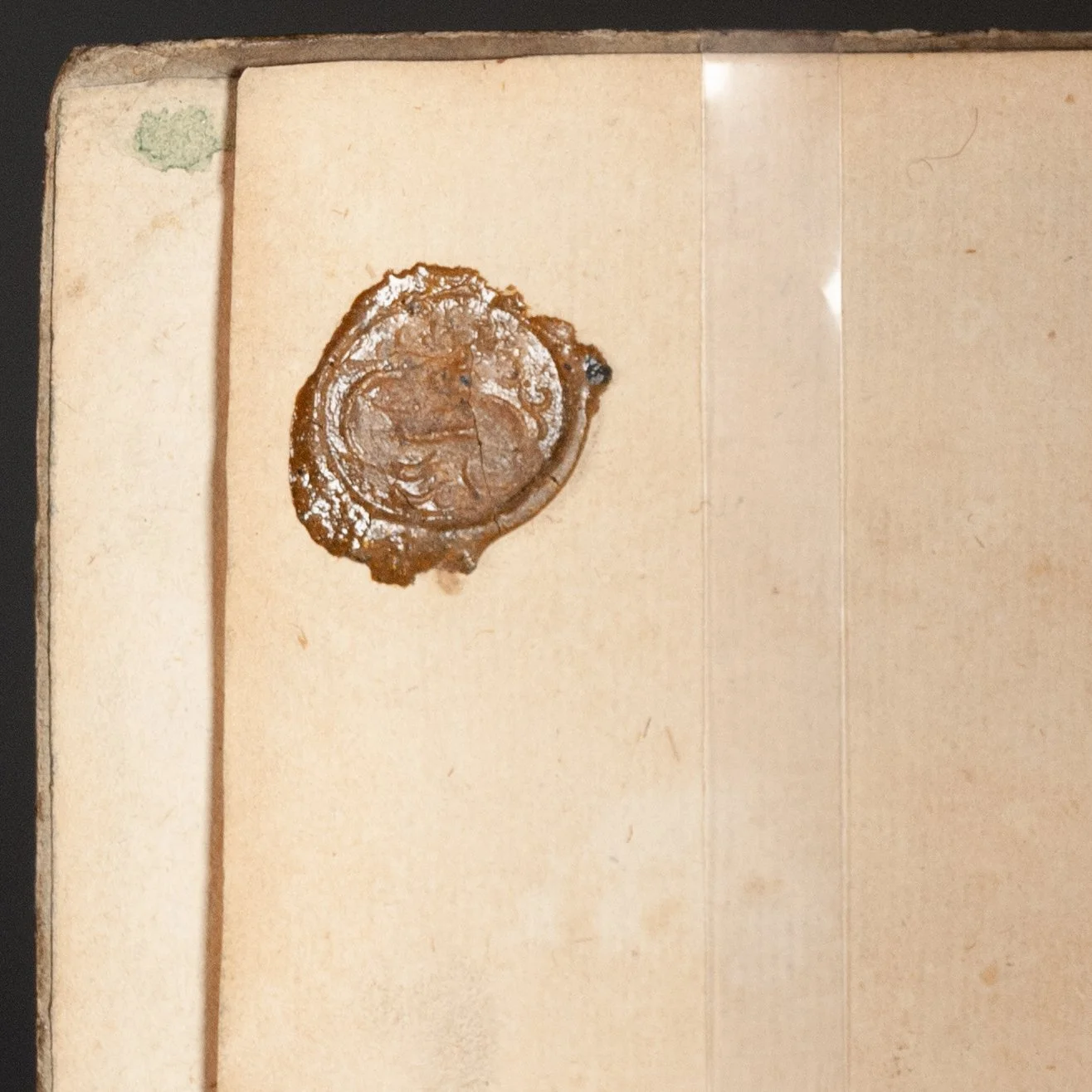

PROVENANCE: Interleaved throughout ca. 1811, with extensive notes of similar vintage on many of the added leaves, altogether some additional 16 pages of handwritten material. These invariably expand on the printed content. Following a section on producing red ink on B4v, for example, our reader has added several lines on Zinnober, or cinnabar, a common mineral pigment for achieving a vermilion color. Opposite instructions for making green ink on C1r, our reader has added further notes for producing a green color. And opposite a section on gilding on C6r, we find a note on using "yellow arsenic" (gelben Arsenic), likely referring to orpiment, a (poisonous) pigment that produced a lemony yellow. This is a model example of the book of secrets used as a bespoke storehouse of additional instructions. ¶ With an old wax seal on the front fly-leaf—perhaps testing one of the recipes found herein?

CONDITION: Bound ca. 1811 in plain boards, the spine covered with sprinkled paper. You may notice gathering E is set with a smaller type than those preceding. We suspect the printer was simply avoiding the need to use an additional partial sheet to finish the edition. All catchwords match up, and it seems very unlikely to have been supplied from another edition. ¶ Title leaf and final leaf both mounted, the former with a little loss, the latter with more substantial loss, including most of the colophon; penultimate leaf torn and repaired; generally trimmed close, but not affecting any text; moderately soiled throughout, the title heavily so. The binding heavily soiled, and worn at the extremities, with a 3.5 cm tear in the paper covering the bottom of the rear joint (superficial damage, as all cords remain firmly intact).

REFERENCES: Librorum Impressorum qui in Museo Britannico adservantur Catalogus (1813), v. 3 (citing a 1567 Halle edition, the earliest we've traced); David Eugene Smith, Rara Arithmetica (1908), p. 323-324 (on the Secretum Secretorum), 303 (on Helmreich: "A Halle Rechenmeister of the latter half of the sixteenth century"); William Eamon, "From the Secrets of Nature to Public Knowledge," Minerva 23.3 (Sept 1985), p. 329-330 (cited above); William Eamon, p. 329-330 (cited above); William Eamon, "Science and Popular Culture in Sixteenth Century Italy: The 'Professors of Secrets' and Their Books," The Sixteenth Century Journal 16.4 (1985), p. 472-473 (cited above), 475 ("The professors of secrets were not, by any means, representatives of the Italian learned establishment. Only one of our authors—Falloppio, who taught anatomy at Padua,was a university professor."), 483 ("Underlying the book of secrets tradition was an entirely new conception of nature and of the aims of scientific inquiry. For the professors of secrets nature was permeated with secrets to which man had reasonable access. Science was not an hermeneutical exercise, an effort to harmonize experience with authority (as almost all medieval science was) but a venatio, or a hunt, a search for secrets that lay hidden in obscure arts and in the deepest recesses of nature itself."); William Eamon, "Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Science," Sudhoffs Archiv 69.1 (1985), p. 27 (cited above; "Why did these writings capture the imagination of Europe in the Middle Ages, and why did their popularity and authority persist so long? One reason, perhaps, is that they were linked with a literary tradition comprising works that promised to reveal the esoteric teachings of revered philosophers like Aristotle and Albertus Magnus...Moreover, books of secrets promised to give readers access to secrets of nature and the arts which might be exploited for material gain or for the betterment of the human condition. Underlying them was the assumption that nature was repository of occult forces that might be manipulated by using the right techniqes."); Ane Ohrvik, Medicine, Magic and Art in Early Modern Norway (2018), p. 34 (on Falloppio's and other books of secrets: "their main goal was to make available various tools and eventually increase self-education in 'how to' by exploring the practical fields of knowledge. As such, the books had a conventional structure and format for the recording of technical processes by providing recipes and lists of ingredients followed by instructions describing the procedures...The goal of providing true and tested knowledge was common to these books."); Heather Jackson, Marginalia (Yale, 2001), p. 25 (“Not scholars or ex-scholars only, but readers of all sorts similarly collected, in the front of their books, materials from other books that could be used as aids and reinforcements for the reading of the book at hand. Notes of this kind are not original, but they indicate by the principles of selection and by the trouble taken to preserve them the frame of mind that the reader considered appropriate in the approach to the work.")

Item #873