Landmark of western thought in the first edition

Landmark of western thought in the first edition

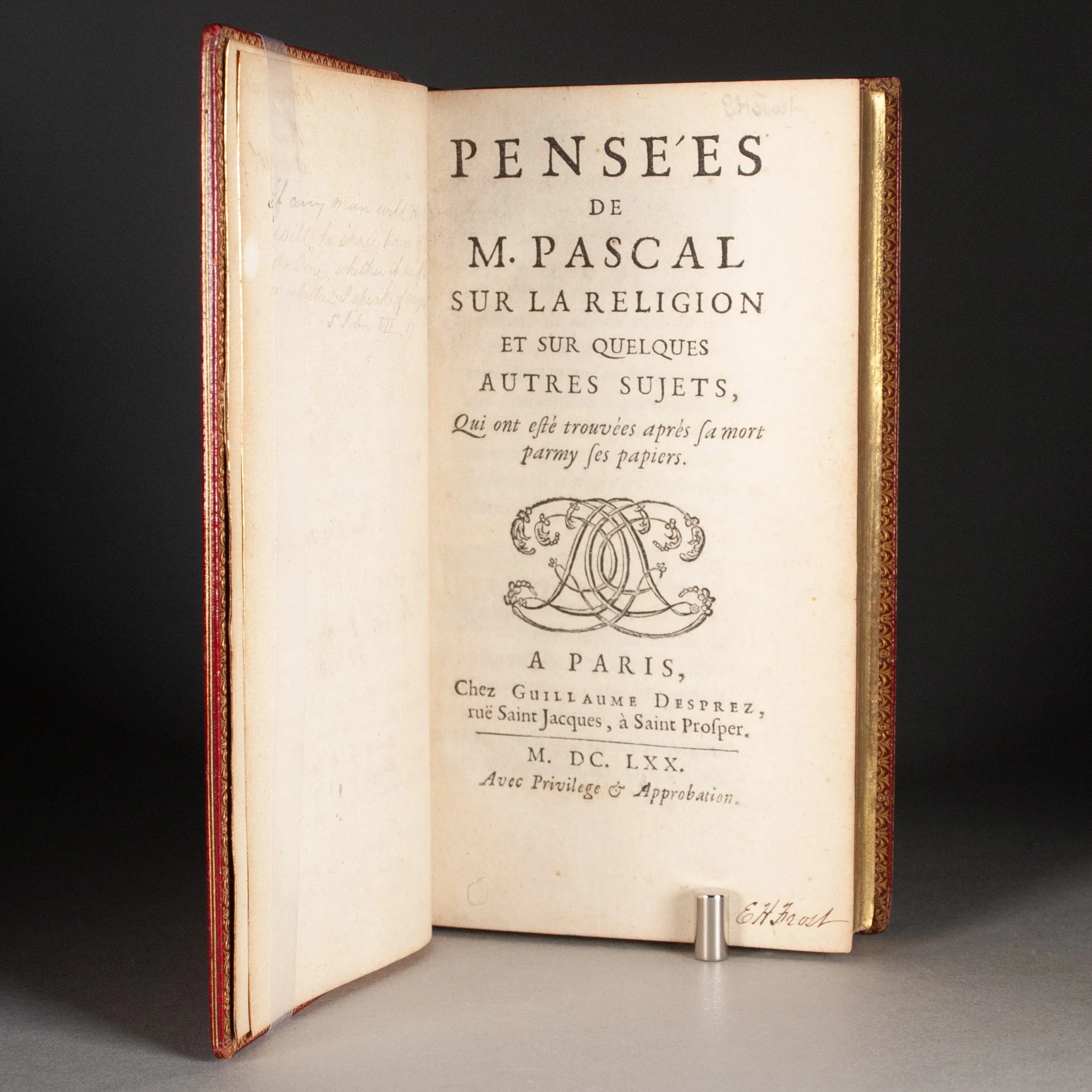

Pensées de M. Pascal sur la religion et sur quelques autres sujets, qui ont esté trouvées après sa mort parmy ses papiers

by Blaise Pascal

Paris: Guillaume Desprez, 1670

[82], 365, [21] p. | 12mo | ã^12 ē^12 ĩ^8 õ^8 ũ1(=S2?) A-P^12 Q^4 R^8 S^2(-S2) | 159 x 88 mm

First edition, second issue—the earliest obtainable—of Pascal's Pensèes, a massively influential landmark of Western thought by the French mathematician, scientist, and philosopher. The first issue of 1669, a tiny run of some 30 copies likely produced for censor approval, has left just two witnesses, both in French libraries. This issue, for all intents and purposes the first published version, appeared early in 1670. Le Guern, for example, calls this issue the édition originale and refers to the 1669 issue as the édition préoriginale. Le Petit provides a detailed account of the textual differences between the 1669 and 1670 issues; the second issue notably includes a far more substantial index and several preliminary approbations. Two or three unauthorized editions also appeared in 1670, variously identifiable for certain pagination differences, or for substituting the Desprez cipher on the title with something else. ¶ Lauded for its timeless assessment of the human condition, acclaimed by many for its modernist flavors, and widely acknowledged as the author's masterpiece—truly something given the litany of his accomplishments—the Pensées has endured as a cultural touchstone since it first appeared more than three and a half centuries ago. "Were it possible to summarize Pascal's action in the seventeenth century in one word, it should be 'subversive.' Like nobody else in the period, Pascal absorbed the modern intellectual trends of the time—many of which were secularizing—in order to subvert and utilize them in favor of a doctrine that Pascal himself characterizes as the most shocking to our reason" (Neto). ¶ The book is a posthumously published collection of fragments that Pascal left unfinished. Scholars have long debated their rightful order, even their intended purpose, but it's clear that Pascal had earmarked many of these pensées (or thoughts) for a larger defense of Christianity. Discovered among his papers after this death, they were ushered through publication—though not without modification—by a coterie of Jansenist friends, who attempted to place them in some kind of logical arrangement (and avoid courting controversy, which seemed to follow the Jansenist movement like a shadow). To call his Pensées a pioneering Christian apology hardly does it justice. While the book has an undeniably religious aim—to convince skeptics they should believe in God—its method is deeply philosophical. Pascal refrains from bombarding his readers with doctrine and dogma, but meets them on their own skeptical ground. Perhaps his most famous tactic—which has proved a significant contribution to the theory of probability—has come to be known as "Pascal's wager," wherein he simply argues that the potential benefits of believing in God (life everlasting, at the relatively low cost of foregoing modest indulgences) far outweigh those of not (eternal torture in hell). "The enduring value of the Pascal's Wager," Joel Hodge observes, "is that, bypassing intractable debates over God's existence, it brings the question of God into a practical, existential focus." ¶ The wager is only the start. William D. Wood argues for Pascal's place among the pantheon of moral philosophers. Graeme Hunter finds in the Pensées a modern approach to addressing the libertine restlessness of Pascal's age. To be sure, the book's ability to engender thoughtful reflection and debate—decade after decade, century after century—must be among its greatest accomplishments. "Certain books seem destined to help each generation determine its own place in history. We identify and characterize separate epochs of history in large part by watching each of them react to the same texts in different ways. In this sense Blaise Pascal's Pensées has played and continues to play an extraordinarily generative role in the Western tradition, with each succeeding generation defining itself and its place in history be responding to Pascal's sharp characterization of the human condition. Neither age nor custom seems able to stale Pascal's infinite variety" (Meskin). ¶ That Pascal could produce a work of such breadth of mind is hardly surprising, given the variety of his contributions to western knowledge. He was an accomplished mathematician and physicist, making important contributions to the theory of probability—a field he is said to have co-founded—and to our understanding of vacuums. He built a calculating machine as a teenager, conducted the first experiment to correlate altitude with atmospheric pressure, is frequently credited with inventing the hydraulic press and the syringe, and even the first public transportation system. "Pascal is by no means a one-work celebrity," that much is clear, "but the Pensées at once crown and illuminate the rest of his life and work" (Krailsheimer). ¶ To dust off a word we use sparingly, an important book.

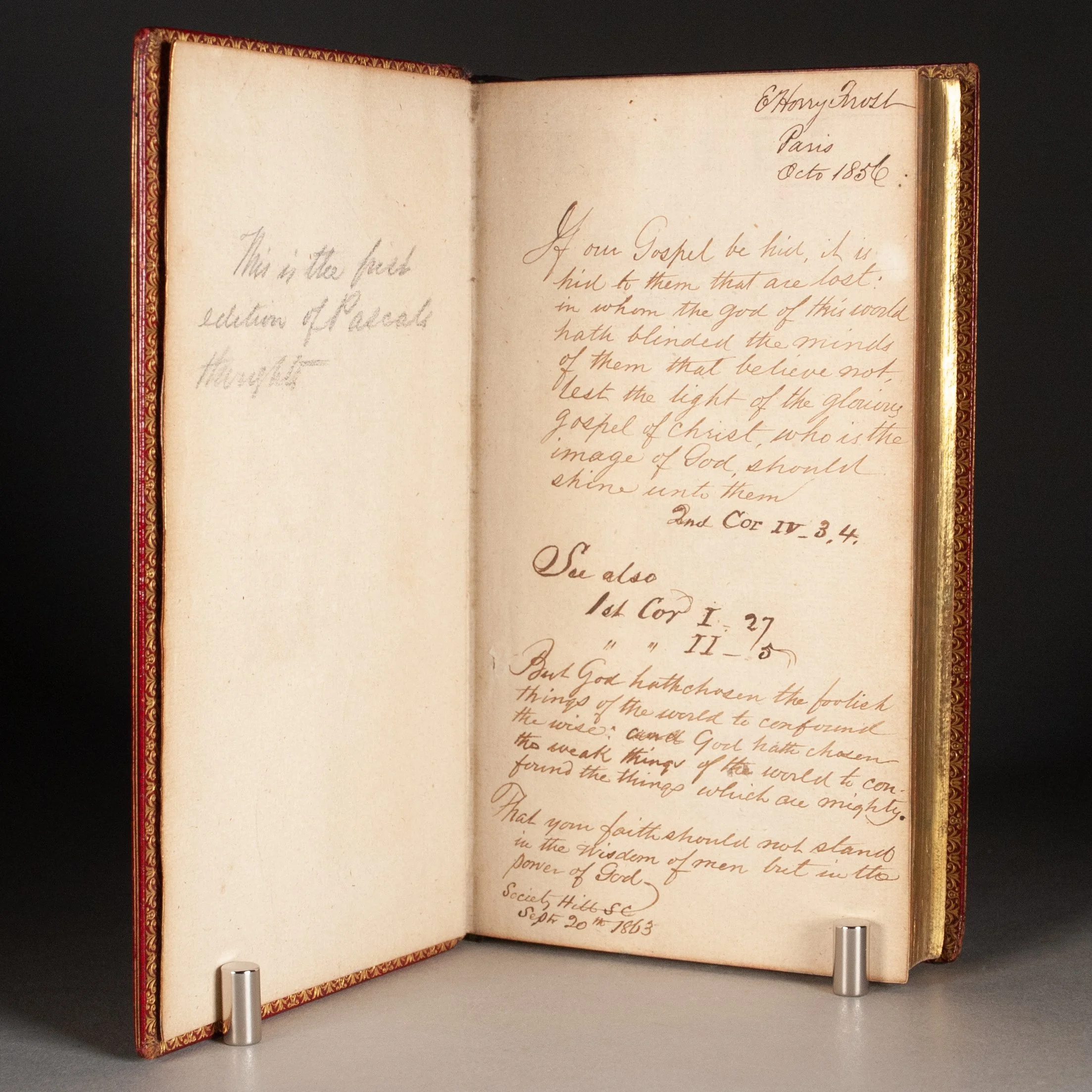

PROVENANCE: From the library of Elias Horry Frost (1827-1897), with his bookplate on a front fly-leaf, his handwritten acquisition note on the next fly-leaf (Paris, October 1856), and his ownership signature both inked and penciled on the title. The Charleston businessman assembled one the greatest collections in the American South at the time. ¶ Front fly-leaf covered in devotional quotes, written beneath them, Society Hill SC Sept 20th 1863. ¶ The last item on the errata list has been struck through in an early hand, as in the Garden-Ritman copy, suggesting the possibility of it being an in-house correction prior to sale. ¶ Clipping from an 1884 bookseller's catalog loosely laid in.

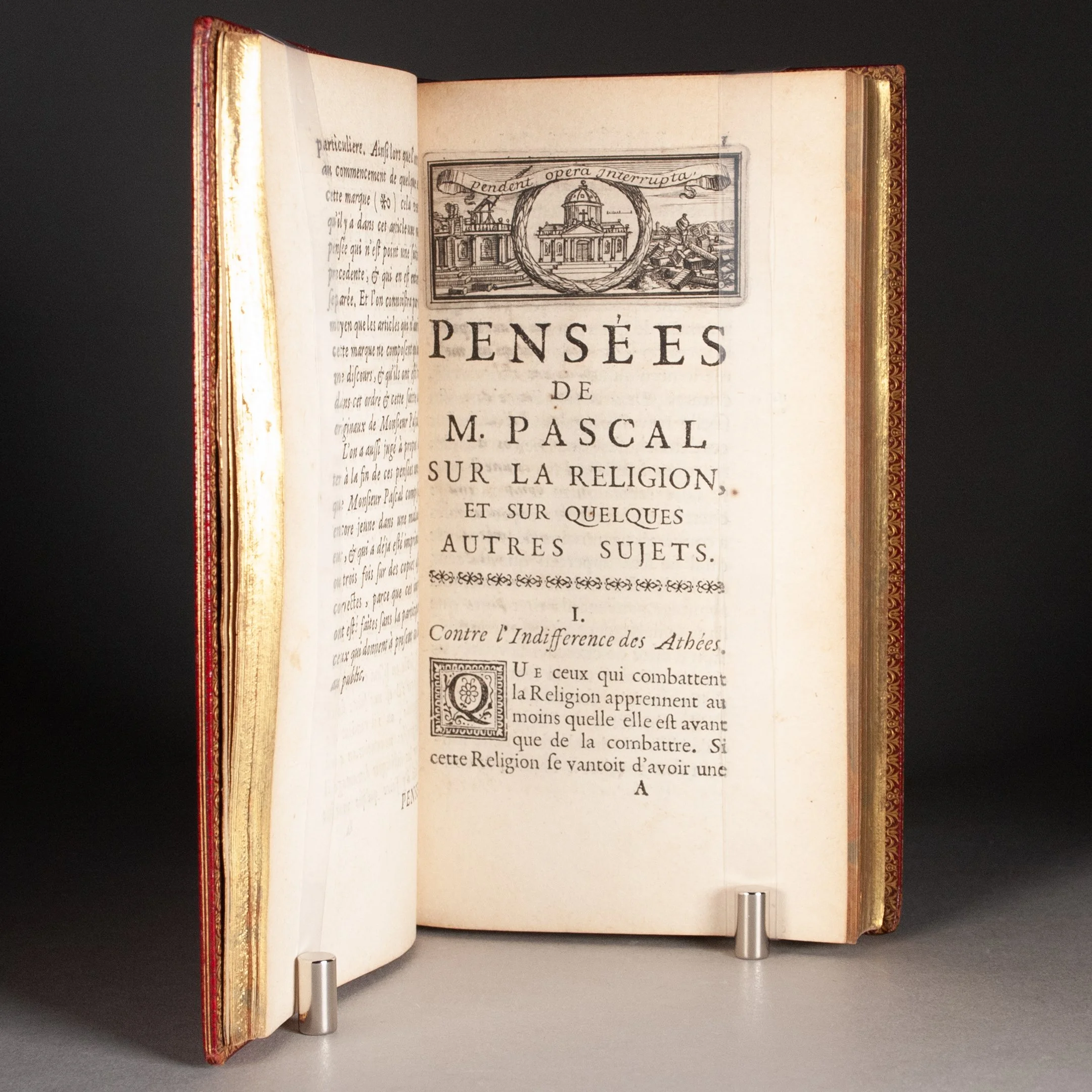

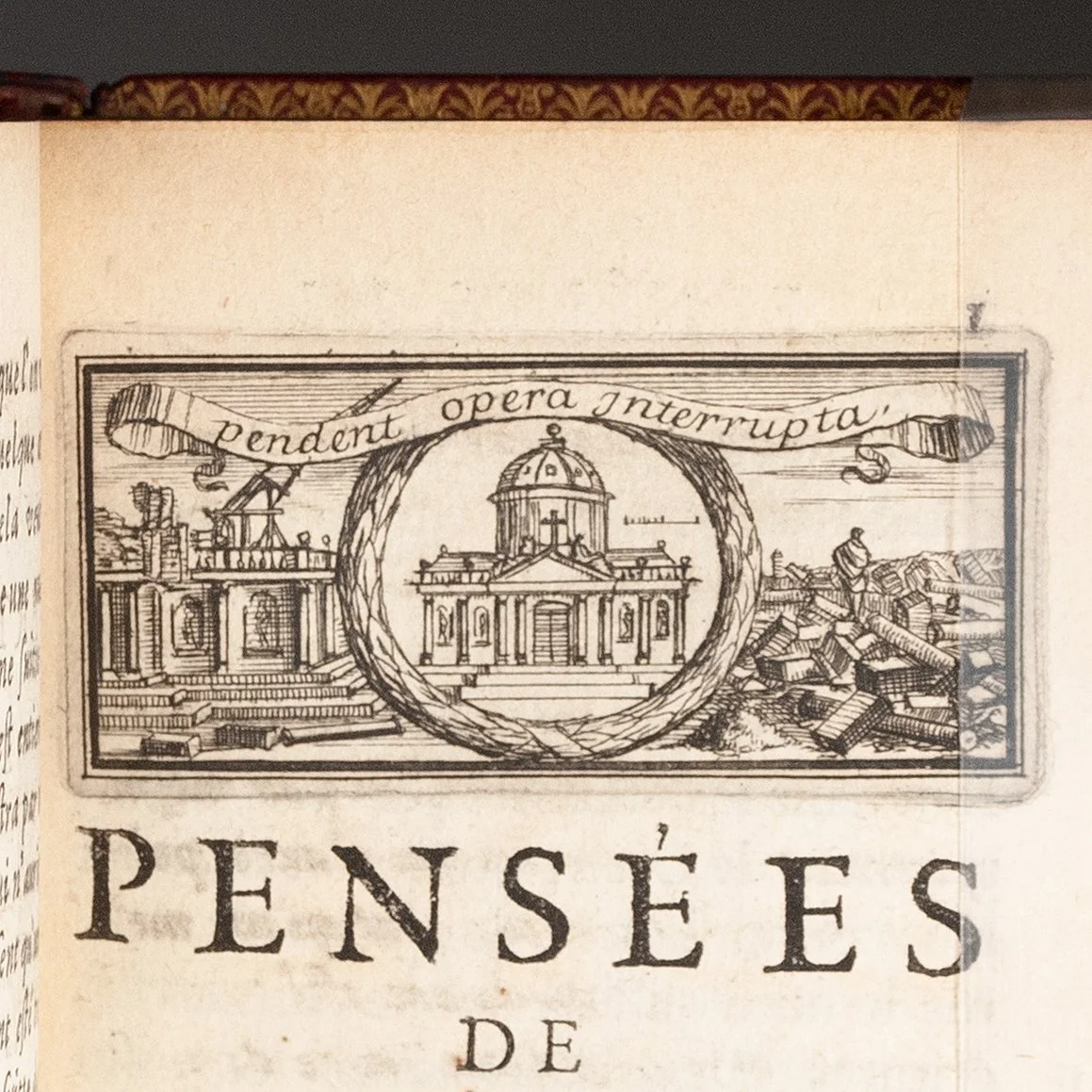

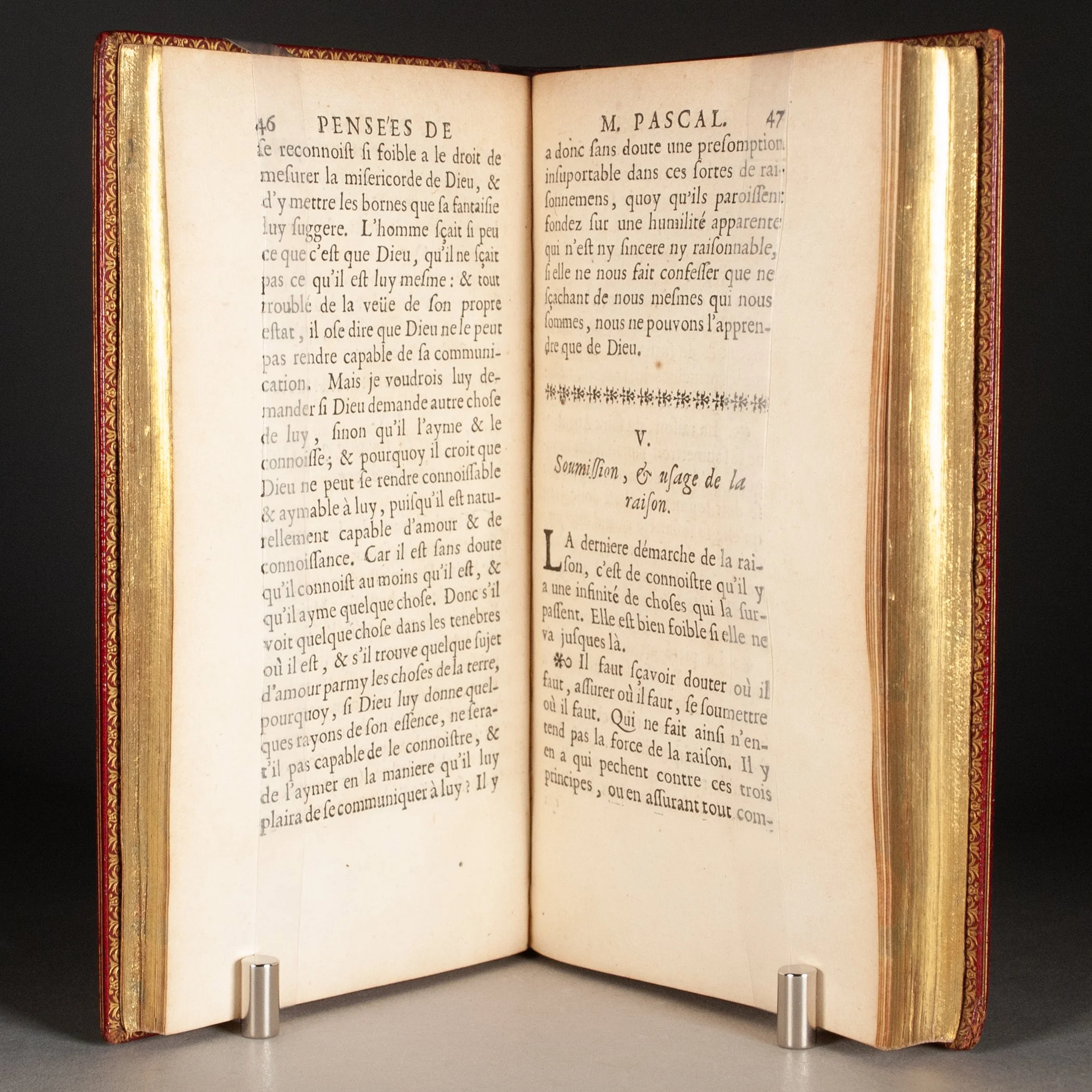

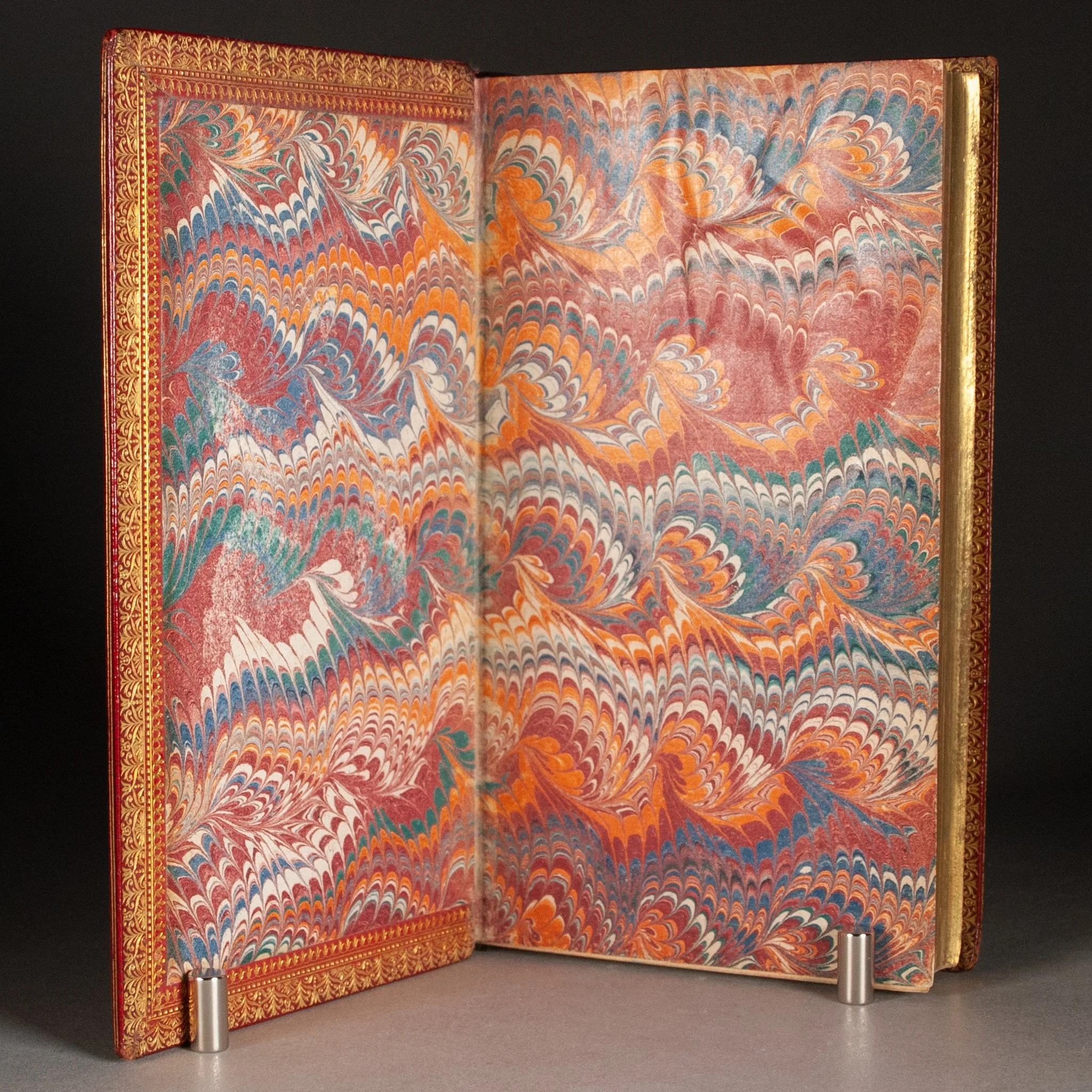

CONDITION: Tastefully bound in red leather by Thompson of Paris (active 1842-1870), in a Jansenist style with simple blind ruling and gilt lettering outside, the turn-ins finely rolled in gilt inside; all edges gilt; marbled endpapers. "He was very addicted to plain Jansenist bindings," Ramsden remarks, something Pascal would surely have appreciated. "His passion for book-collecting is said to have dissipated his earnings as a binder." With the publisher's cipher on the title, and a few decorative initials and head-pieces, including a charming etched head-piece on p. 1. ¶ Occasionally a trifle dusty, and some very marginal staining to a few leaves near the end, but really very nice internally. Front joint very discreetly repaired in the top compartment; some negligible soiling to the leather; lower corner of rear board just barely bumped. Quite a nice copy, both inside and out.

REFERENCES: Albert Maire, Pascal philosophe: Les pensées; éditions originales, réimpressions successives (1926), p. 101, #3 (citing the second issue with seconde édition on title); Michel Le Guern, Oeuvres complètes / Pascal (2000), v. 2, p. 1597, Edition O; Tchermerzine, Bibliographie d'éditions originales et rares d'auteurs français (1933), v. 9, p. 73; Brunet, Manuel du libraire, v. 4, col. 398; Printing and the Mind of Man (1967), p. 90, #152 ("Pascal's work has, in fact, the marks of genius, exploring and stating all that can be said on both sides of the question it investigates...This is not a book which one can measure as a totality in terms of orthodoxy or the reverse. It is, however, a book for which the enquiring mind has had solid reason to be grateful from its first imperfect publication to the present day.") ¶ Jules Le Petit, Bibliographie des principales éditions originales d'écrivains français (1888), p. 208 (suggesting the 1669 issue was prepared for censors, based on changes made in the 1670 issue; a full account of textual differences follows); José R. Maia Neto, "Blaise Pascal," The Columbia History of Western Philosophy (1999), p. 357 (cited above); William D. Wood, "Axiology, Self-Deception, and Moral Wrongdoing in Blaise Pascal's Pensées," The Journal of Religious Ethics 37.2 (Jun 2009), p. 356 ("Pascal is much more than a religious moralist with a fine prose style. He is also an important moral philosopher, one who deserves a place alongside the other, more systematic, ethicists of the early modern pantheon."); Graeme Hunter, "Motion and Rest in the Pensées: A Note on Pascal's Modernism," International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 47.2 (Apr 2000), p. 91 ("The wager is of course one of the justly celebrated contributions of the Pensées, and it is also one of its distinctly modern features, the science of probability having been born with, and in part through, the Pensées"); Joel Hodge, "Pascal's Wager Today: Belief and the Gift of Existence," New Blackfriars 95.1060 (Nov 2014), p. 698 (cited above); Jacob Meskin, "Secular Self-Confidence, Postmodernism, and Beyond: Recovering the Religious Dimension of Pascal's Pensées," The Journal of Religion 75.4 (Oct 1995), p. 487 (cited above); E.B.O. Borgerhoff, "The Reality of Pascal: The Pensées as Rhetoric," The Sewanee Review 65.1 (Jan-Mar 1957), p. 15-16 (on the original state of Pascal's fragments: "Pascal had made up a number of bundles obviously destined for a work of Christian apologetics he had been preparing; there was in addition a bundle of notes for a treatise on miracles; but there was also a considerable mass of unclassified papers"); John Cruickshank, "Pascal, Blaise," The New Oxford Companion to Literature in French (2005; "There is no doubt that Pascal's greatest work remains the Pensées," which "use an analysis of the problem of human nature in order to interest the reader in the Christian solution"); A.J. Krailsheimer, "Introduction," (1984), 11 (cited above); Charles Ramsden, French Bookbinders 1789-1848 (1989), p. 202 (cited above)

Item #886