Nuremberg Chronicle manuscript fragment

Nuremberg Chronicle manuscript fragment

[Manuscript fragment from a copy of The Nuremberg Chronicle]

by Hartmann Schedel

[ca. 1600?]

1 fragment | 188 x 321 mm

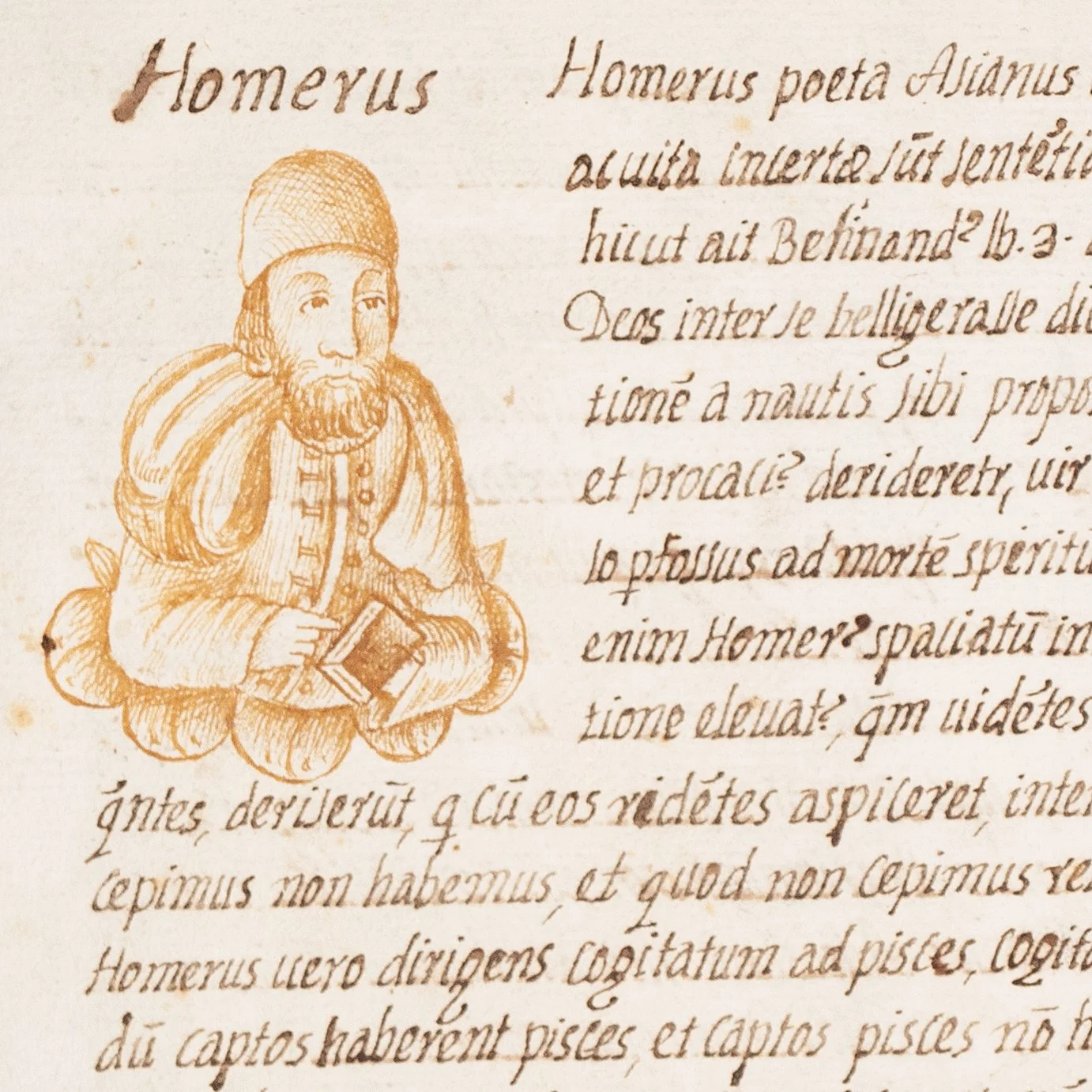

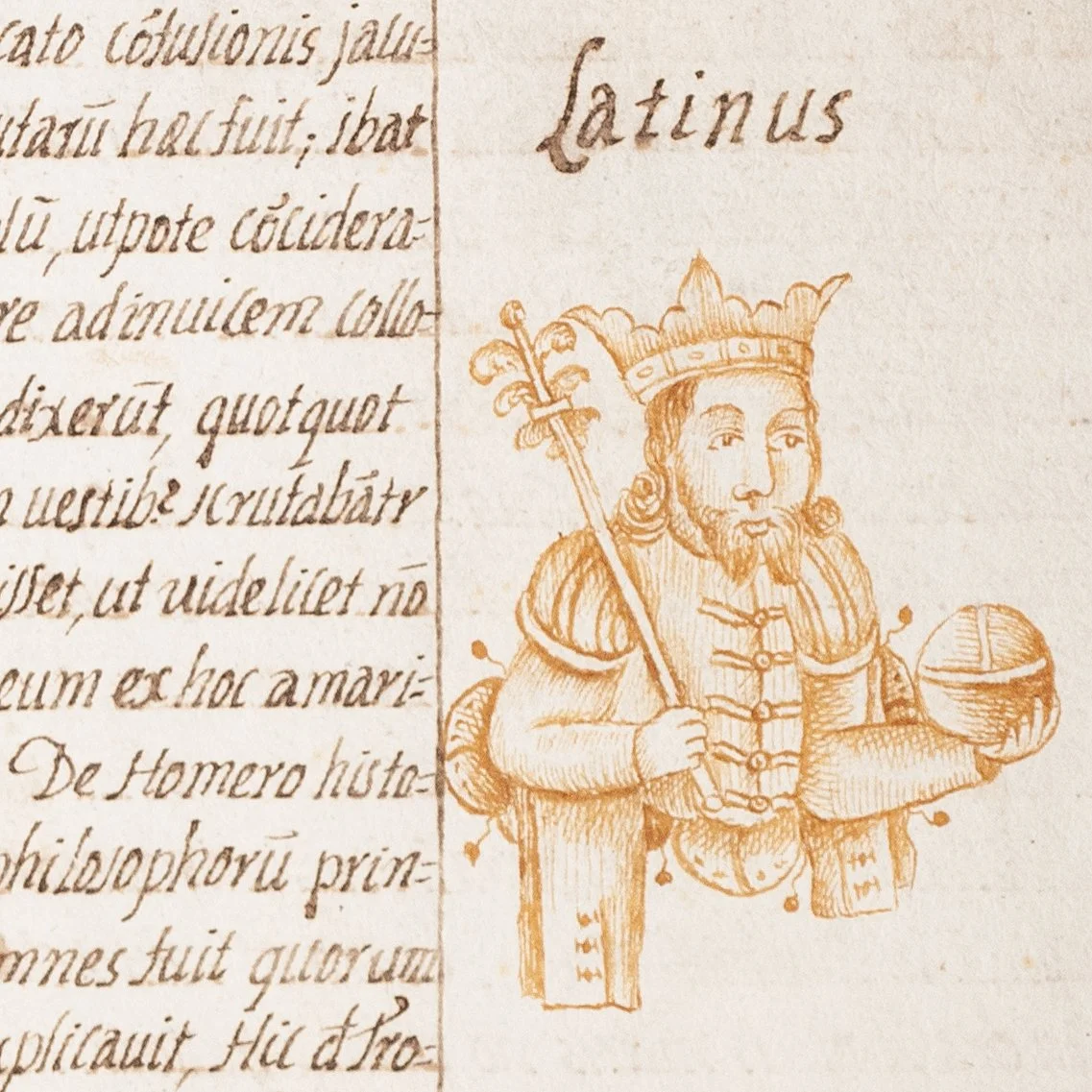

A fragment preserving the upper 40% of a manuscript copy of folio XLIII from the 1493 Latin edition of the Nuremberg Chronicle. Rather than a fragment of a complete manuscript copy, we suspect this was meant to replace a bifolium that came to be missing from a printed copy. Such defects could stem from a number of causes. During the incunable period, for example, it wasn't terribly unusual for books to find their way to booksellers minus a gathering or two, or with some sheets destroyed in transit. And of course wear and tear over the years could necessitate eventual replacement. ¶ In the best examples of pen facsimile work, the scribe will painstakingly copy the printed letterforms, rendering them almost indistinguishable from the original. Our scribe made no such effort with their letters, though we're still quite taken by the inked illustrations. These are recognizably reproductions of the original woodcuts, but not without some artistic license. Here, for example, Homer is holding a book, whereas his hands are empty in the printed edition. Supplying missing printed leaves with handwritten substitutes had been a standard practice since the earliest days of print, but the the practice of true pen facsimile work expanded alongside the concept of the collectable rare book. By the 19th century it was something of a cottage industry. ¶ Our scribe made liberal use of old Latin abbreviations not found in the printed original, so we're inclined to date this prior to the 18th century at least. At the same time, the manuscript replaces the printed text's roman numerals with arabic numerals, so we hesitate to call it contemporary with the book's original appearance. A few of the more distinctive letterforms, like uppercase E, we find in penmanship books as early as the late 16th century. ¶ A fantastic relic that bears simultaneously on print and manuscript, and a wonderful thing to pair with a copy of the printed edition.

CONDITION: Handwritten in brown ink on a partial sheet of laid paper (missing the half that may have borne a watermark). ¶ Mild dampstaining in the upper right corner of the recto, affecting some text; top edge and fore-edge a trifle ragged, with a few small closed tears; a few spots of wormed loss repaired, and the fold of the bifolium reinforced.

REFERENCES: Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin, The Coming of the Book (1976), p. 222 (shipping books in sheets was often problematic; "The man who got the consignments ready in the shop had to see that the right sheets were included in the correct order. Many mistakes were made and booksellers' correspondence of the period is full of demands for missing sheets needed to complete defective volumes...There were only two forms of transport available, boat and wagon, so that books risked being ruined by seawater at the bottom of a ship's hold or by rainwater in a carrier during bad weather. Normally they were placed in great wooden crates for protection, but even so they often arrived soaked or otherwise damaged, and when books were transferred from one vehicle to another several times during a journey the risk was even greater.")

Item #860