Movable calendars

Movable calendars

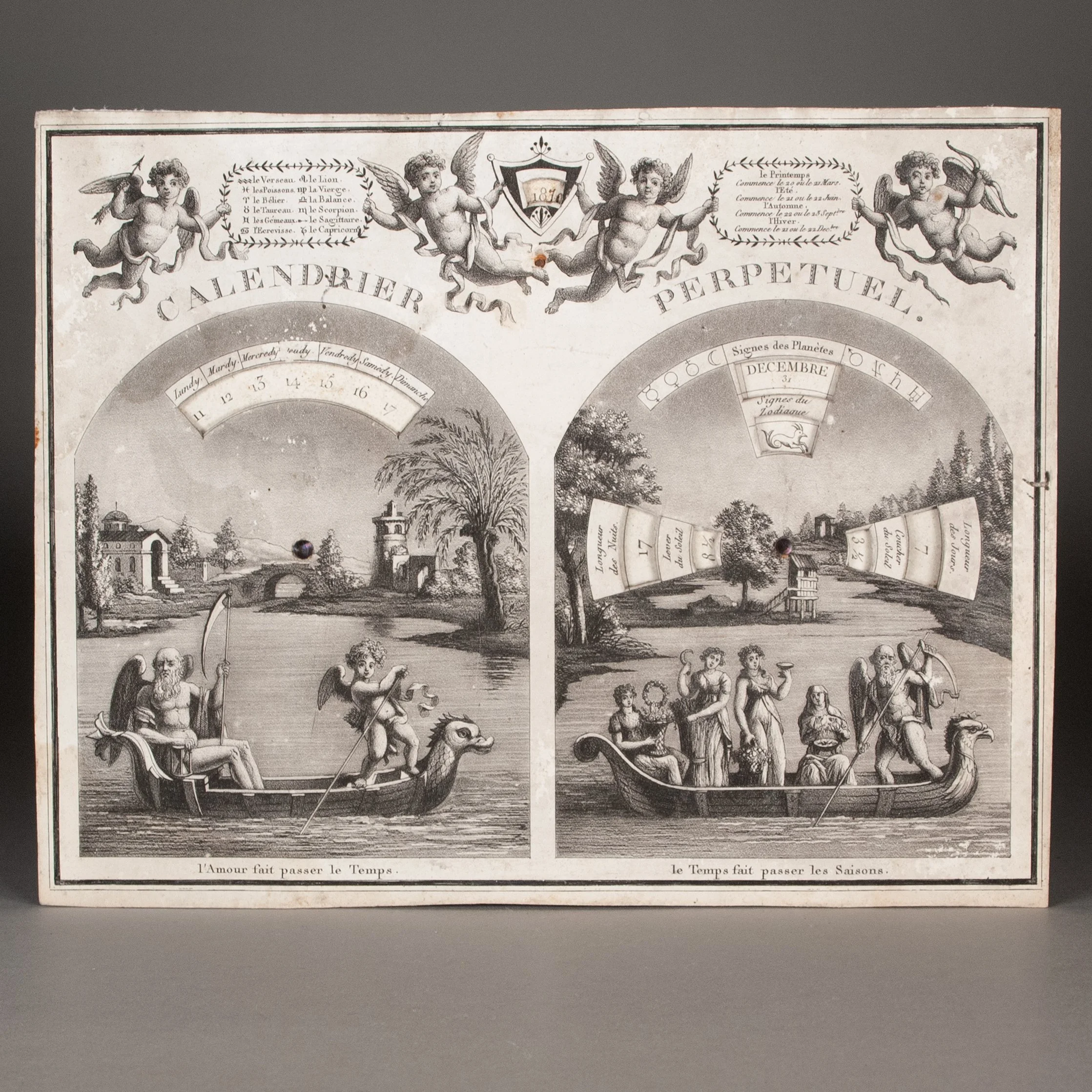

[Three movable perpetual calendars]

[France and Germany, 1783-ca. 1830]

3 pieces | 194-335 x 248-480 mm

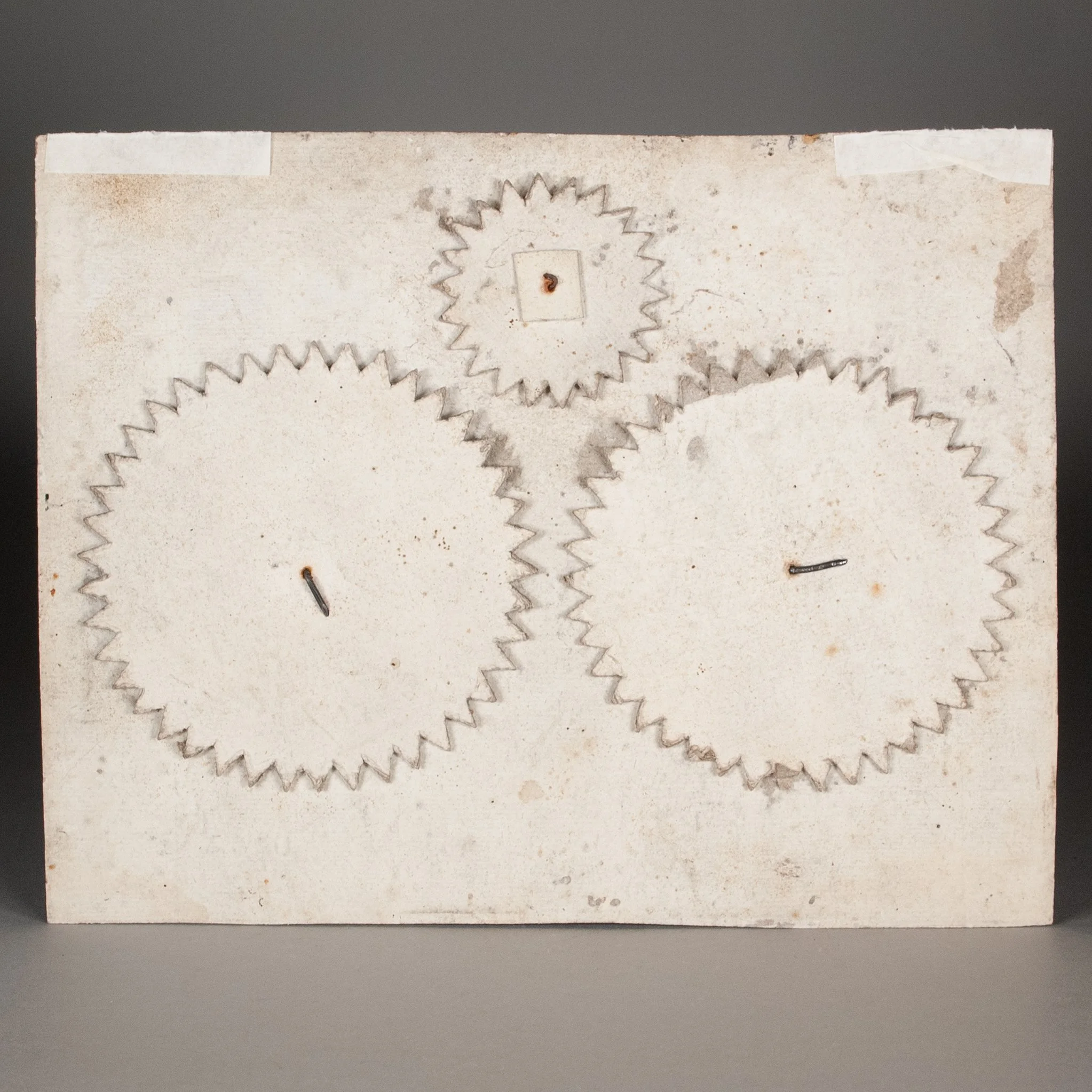

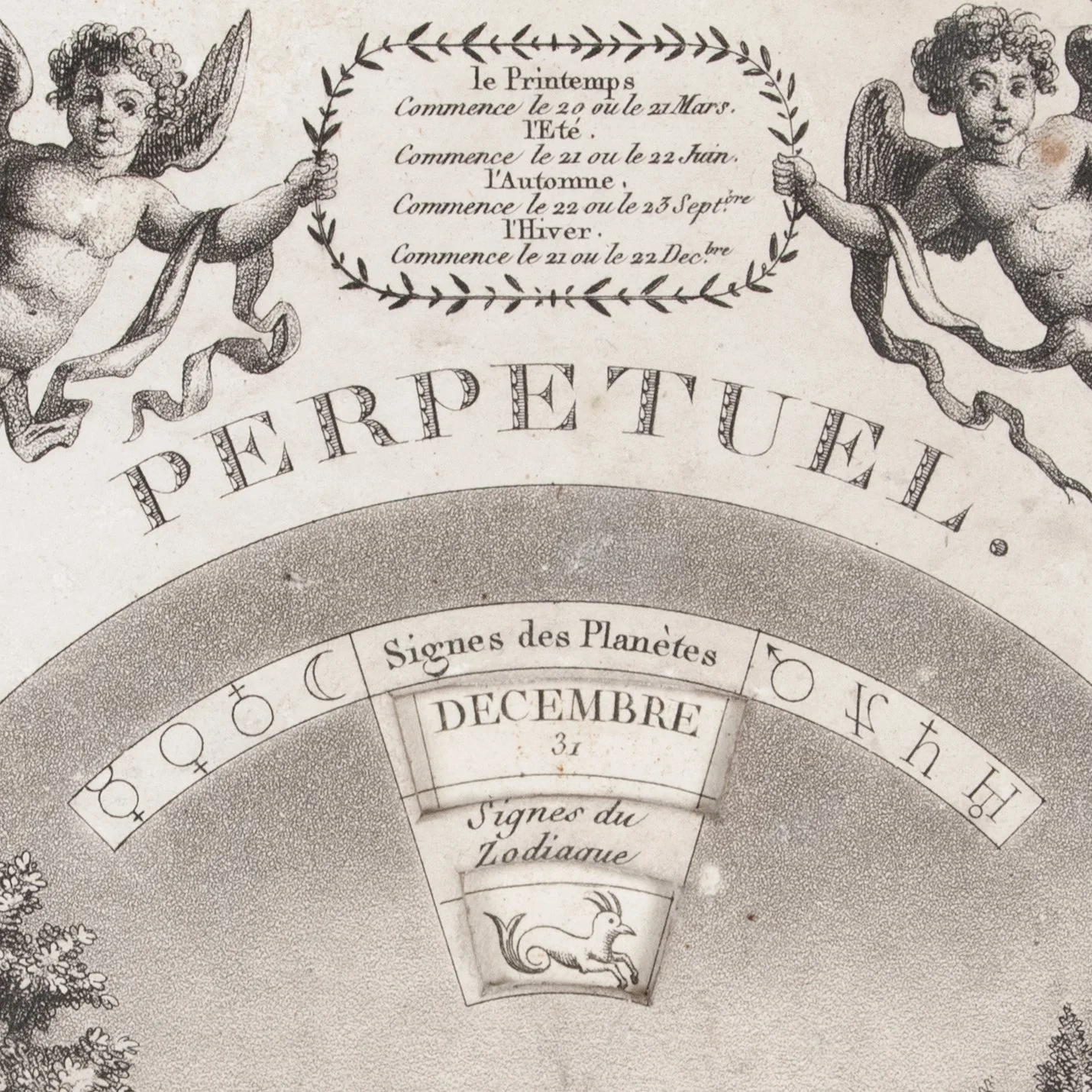

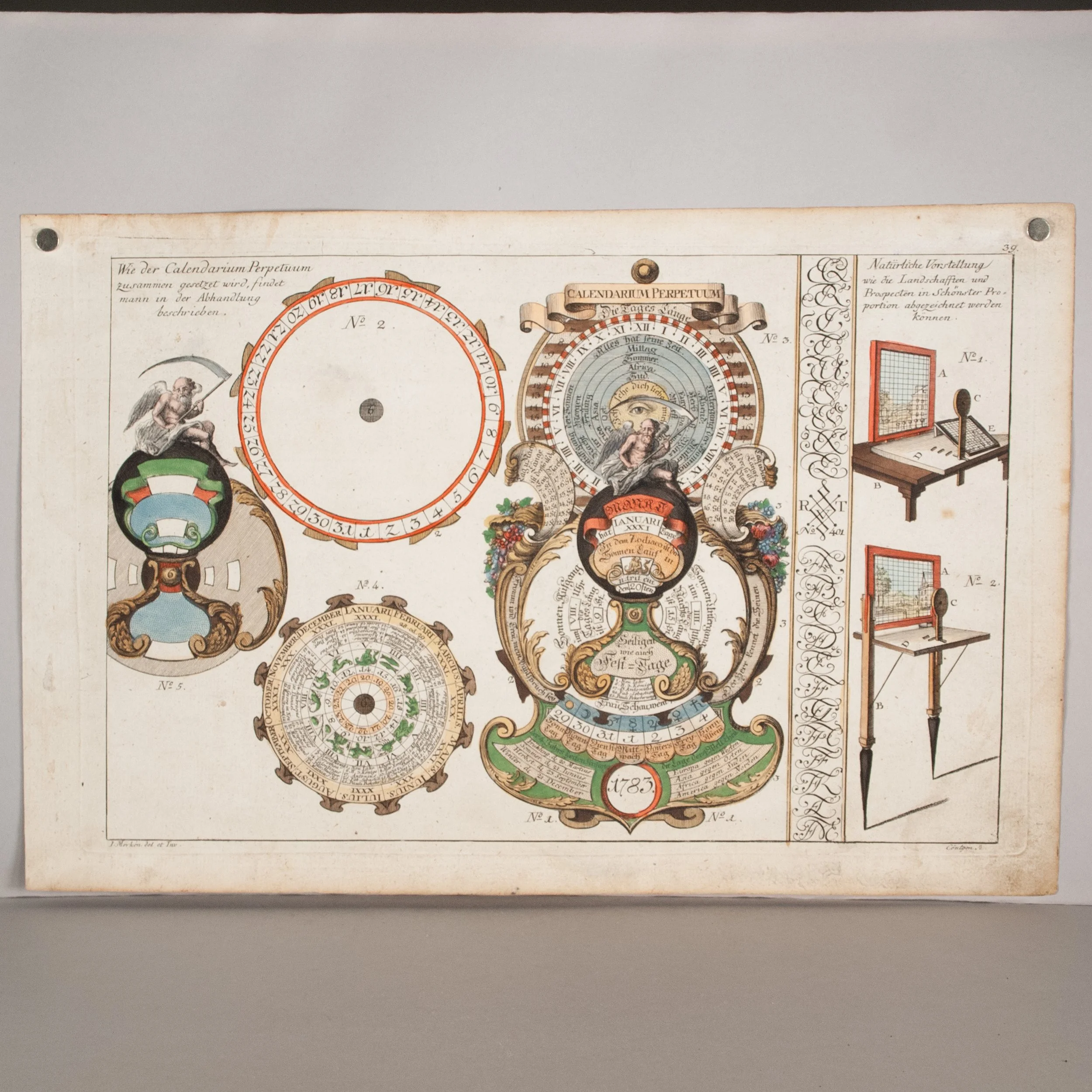

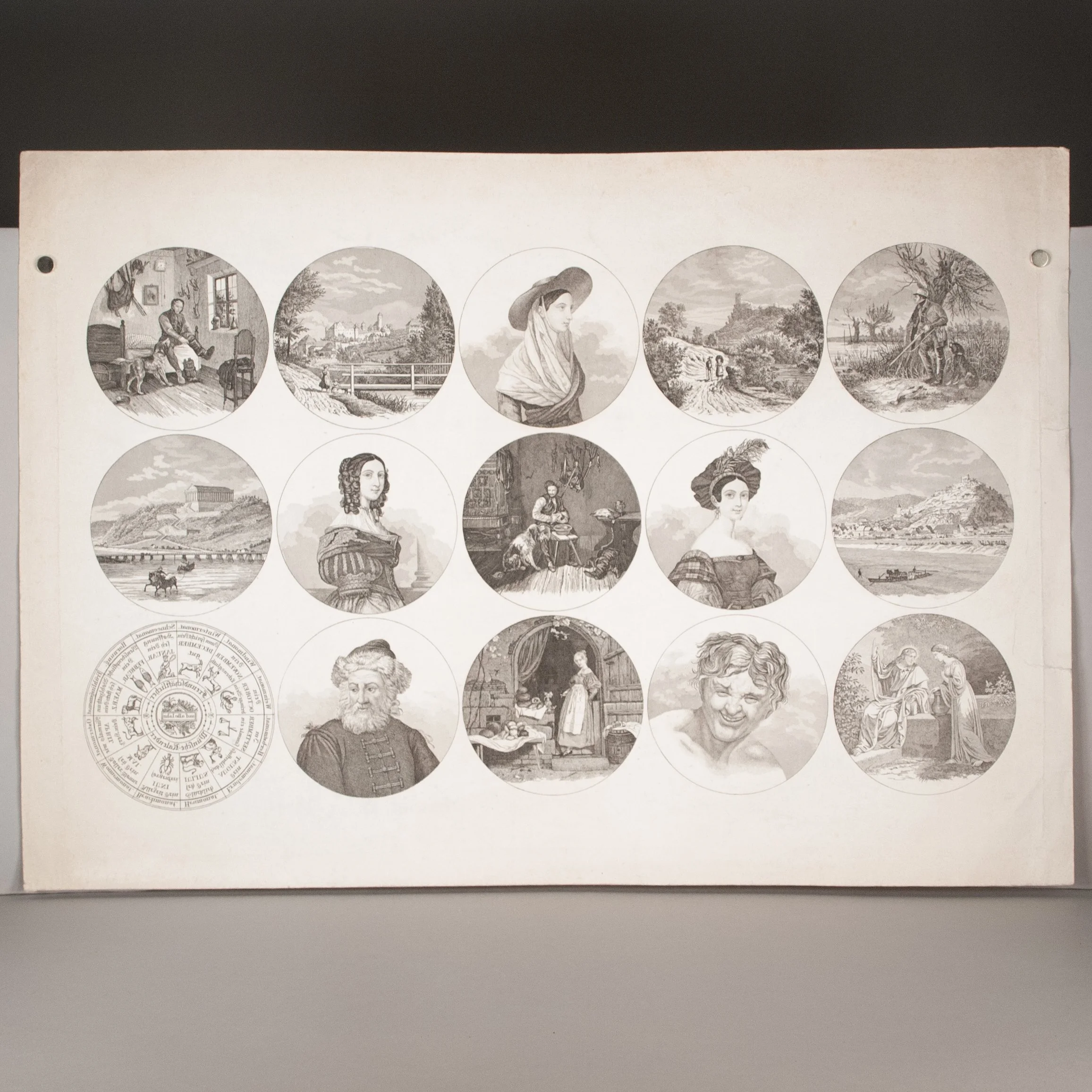

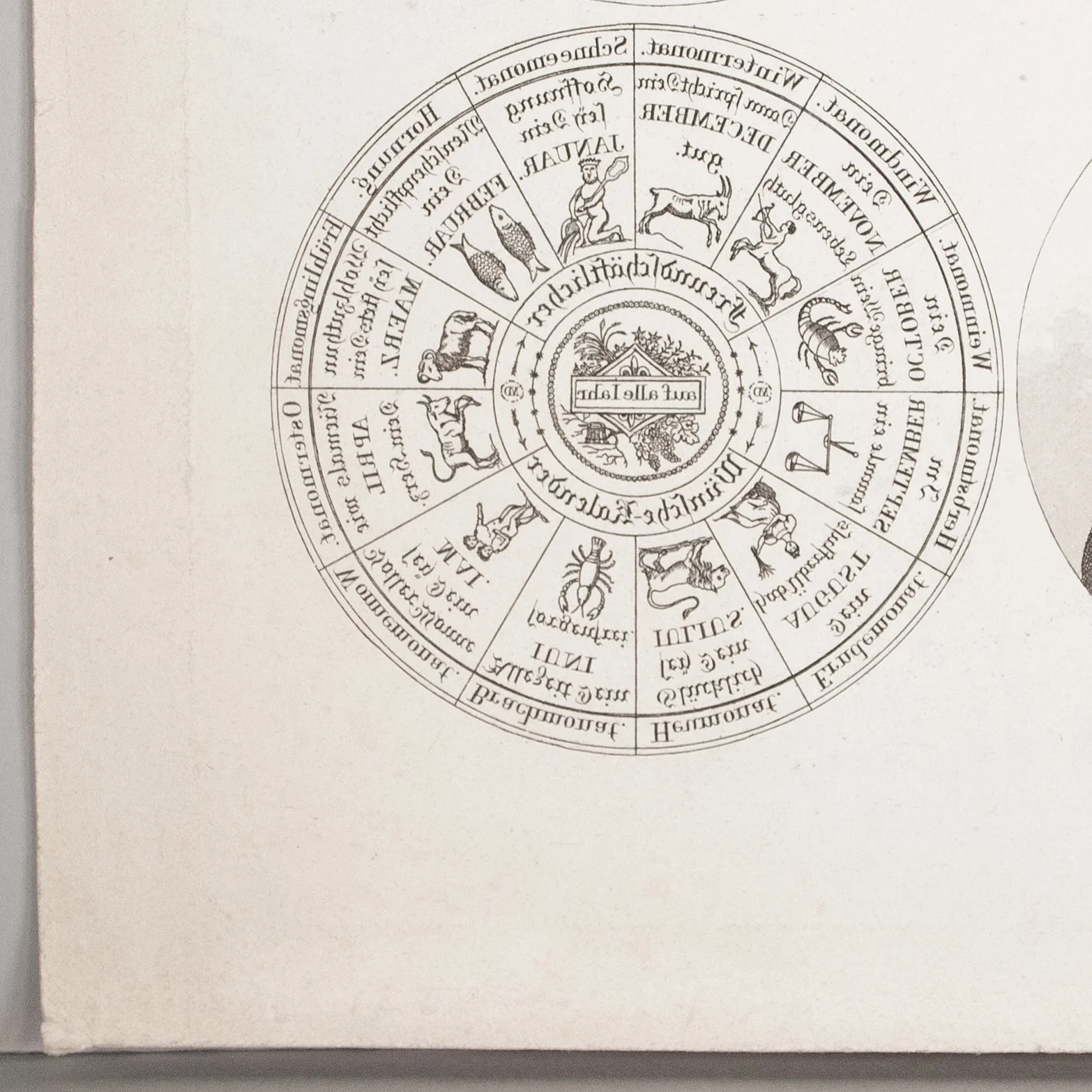

An instructive trio of movable perpetual calendars: one of them fully assembled and functional, one with its elements uncut as issued, and one that appears to represent the zodiac dial only (in rather baffling context). As a genre, the perpetual calendar (or perpetual almanac), dates to the middle ages. Even if limited to feast days, you'll find readily accessible ancestors in those calendars and almanacs commonly appended to books of hours and liturgical texts. They offered the means to find the chronological details of any given day well into the distant future—for nearly a decade, in the case of our Calendrier perpetuel. They could (and did) foretell much further in tabular form, when not limited by the strictures of a conveniently sized dial, though this volvelle-based format enjoyed enduring appeal. Nor was the format by any means limited to paper. The La Jolla Map Museum's San Zeno Wheel, for example, is a massive mid-15th-century wooden version, and pocket-sized silver examples enjoyed a certain vogue in 17th-century England. But as you might imagine, paper versions of these instruments—of all scientific and mathematical instruments, really—were far more prone to wear and tear. ¶ The intricate illustrations of our French Calendrier perpetuel were achieved through a combination of mezzotint and etching, these accompanied by engraved text (including the three dials). The whole thing (194 x 248 mm) was mounted on thick board, likewise the dials, attached to the main board with metal pins. Printed for the years 1810-1818, the calendar provides the complete zodiac, dates and days of the week, the lengths of night and day, and times of sunrise and sunset. At top is a legend identifying the signs of the zodiac, plus a reminder of when the four seasons begin. The scene at left depicts Cupid pushing Father Time in a gondola (L'amour fait passer le temps), and that at right has Father Time with personifications of the four seasons (Le temps fait passer les saisons). ¶ The German Calendarium Perpetuum is dated 1783, was designed by Johann Merken and engraved by Franz Anton Cöntgen, and provides a hair more information than the French example. We've been unable to examine a copy, but we suspect this comes from Merken's Liber artificiosus alphabeti maioris (1782-1785; note plate number 39 in the upper right). The finely hand-colored sheet (232 x 356 mm) contains four elements that could theoretically be cut out and assembled to form a movable perpetual calendar, though the plate size necessarily left the element bearing the windows incomplete on its left side. Was the user expected to complete it on their own, which should have been easy enough? Or was this strictly meant as an illustrative model? We lack the explanatory text, apparently not an unusual state of affairs for this particular book, at least according to a pair of booksellers in the 1890s. Immediately right of the calendar is a narrow column of decorative letters, then an illustration of an apparatus meant to assist with perspective in drawing. ¶ The third sheet (335 x 480 mm) is the most obscure. It bears fifteen round etchings, each roughly 8 cm in diameter, the bottom left of which is a Freundschäftlicher Wünsche-Kalender. It looks much like the zodiac dial for a perpetual calendar, though we find no trace of it in the vast digitized corpus online. The remaining illustrations comprise a hodgepodge of popular themes: ladies' fashion, historic vistas, country life, even a devotional scene. White space remains at the bottom of several of these, as if for brief captions (avant la lettre, as the histoire du livre might speak of such a state). If that's not enough to suggest a proof sheet, then the zodiac disc, which was engraved backwards—we used a mirror to assist our reading—surely should. Perhaps the calendar never developed beyond this grossly mistaken proof stage. This sheet was printed on machine-made wove paper and we date it ca. 1830. Look closely when backlit and you'll see a faint watermark running down the middle, which we suspect was the seam of the continuous wove mold used in papermaking machines. ¶ An uncommon opportunity to examine three different perpetual calendars in three different states of production.

PROVENANCE: A later user appears to have repurposed the Calendrier perpetuel for use in 1865-1874 (skipping 1871). Note the alterations made by hand to the year dial at top center.

CONDITION: The Calendrier and proof sheet moderately soiled, and both with remnants of discreet paper hinges on the verso; we suspect the pins for the Calendrier's dials were replaced, perhaps when it was repurposed in 1865; the proof sheet with a few tears and creases, both of the former repaired, and neither more than an inch long (not affecting image).

REFERENCES: Sarah Griffin, "Synchronising the Hours: A Fifteenth-Century Wooden Volvelle from the Basilica of San Zeno, Verona," Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 81 (2018), p. 35-37 (description of the San Zeno Wheel, and noting its similarity to contemporary vellum manuscript versions); A.J. Turner, "A Seventeenth Century Calendar Scale for Coins and Mathematical Instruments," American Journal of Numismatics 5/6 (1993/1994), p. 212 (for silver examples in England); Bulletin de la société des sciences, lettres & beaux-arts de Cholet (1892), p. 312 (recording a donation of what sounds like our Calendrier perpetuel, though multiple such editions appear to have existed); Karl W. Hiersemann, Kunstgewerbe VI. Buchgewerbe (1894), p. 17, #232 ("The text is missing in most examples"); Joseph Baer & Co., Kunstgeschichte Deutschlands und die Niederlande (1890), p. 23, #6065 (the text "almost always missing"); Suzanne Karr Schmidt, Interactive and Sculptural Printmaking in the Renaissance (2018), p. 210 (speaking of 16c paper instruments: “Despite their rarity today, the wide availability of these cheap alternatives to metal instruments remains unquestionable"); Susan Dackermann, Prints and the Pursuit of Knowledge in Early Modern Europe (2011), p. 267 (also on 16c paper instruments: “Few examples of even the most rudimentary printed instruments survive, however, suggesting that they were assembled and worn out through use")

Item #843