Manuscript science coursebook with rare illustrations

Manuscript science coursebook with rare illustrations

Physica generalis

[France, ca. 1734]

115, 117-130, 132-182, 184-276, 278-433, 433-435, 435-588, 588-597, [304] p. + [37] plates (most folding) and [1] thesis broadside (folded) | 4to | 227 x 167 mm

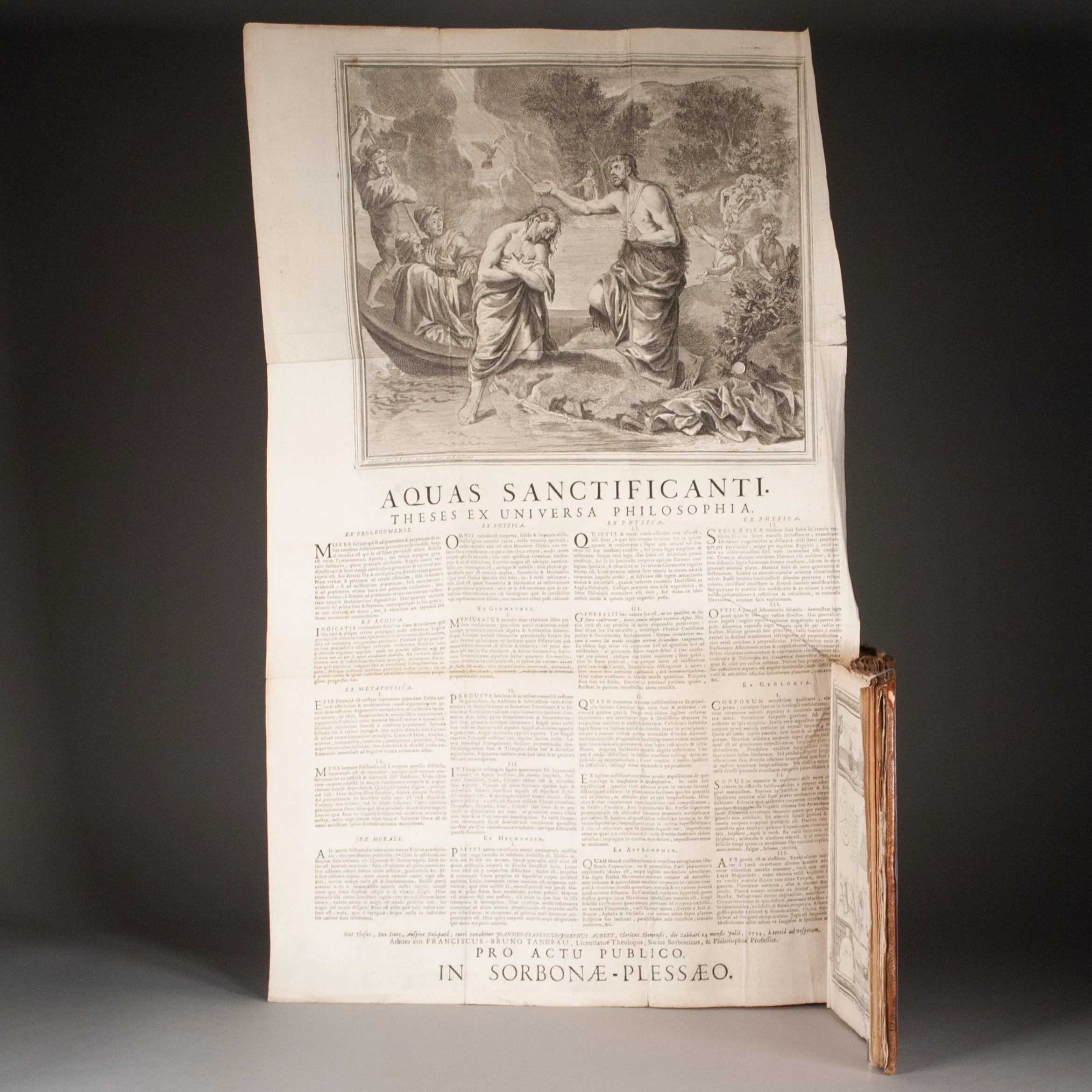

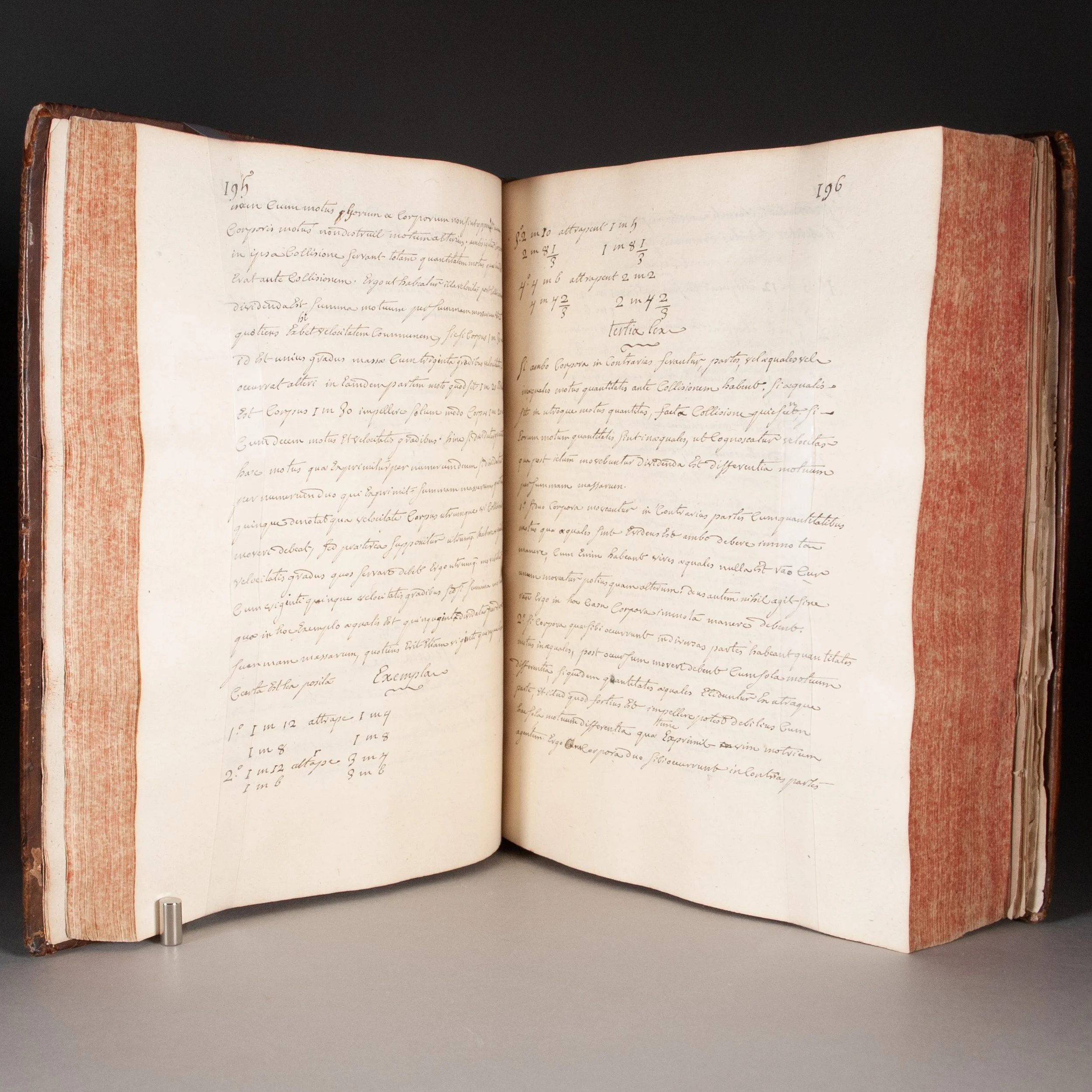

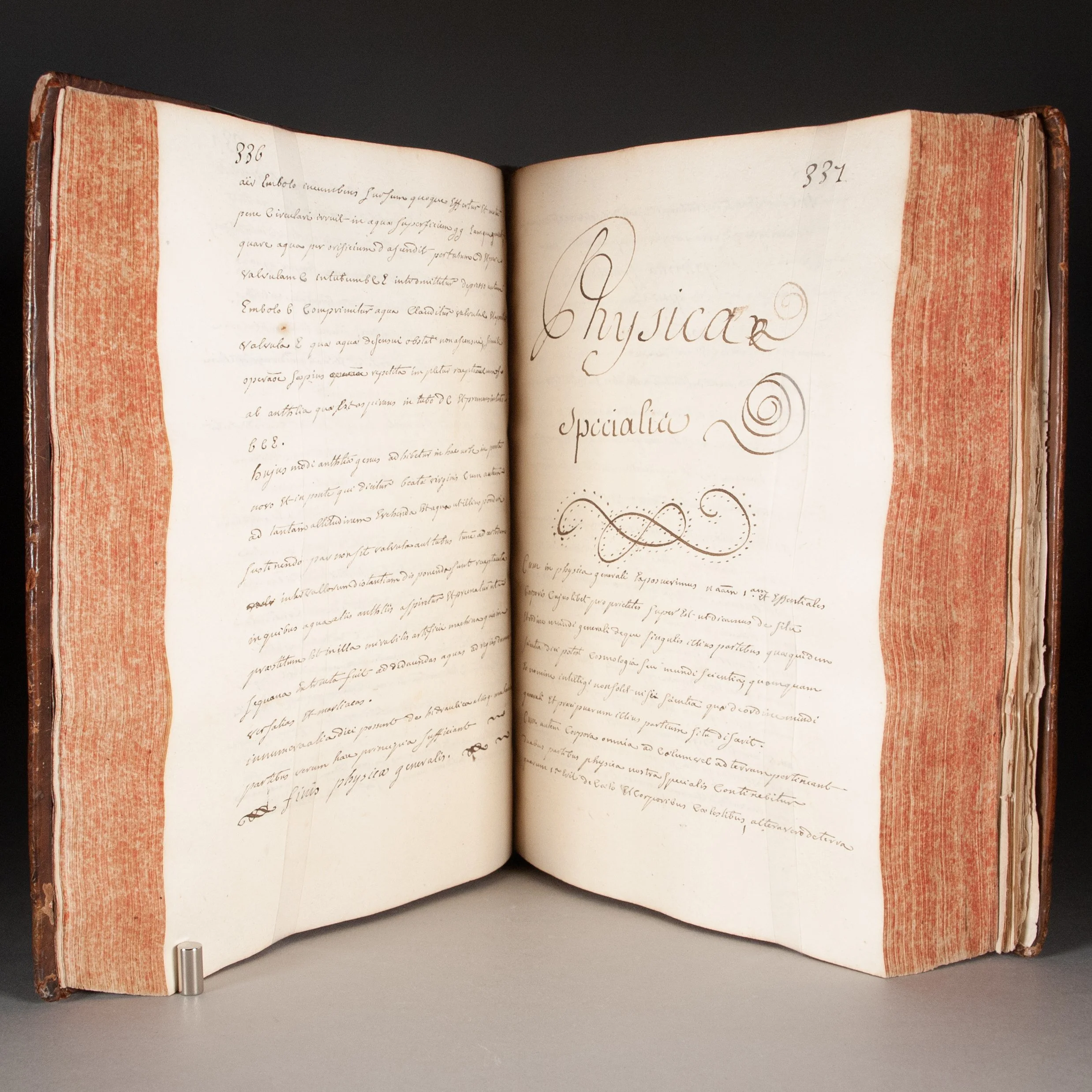

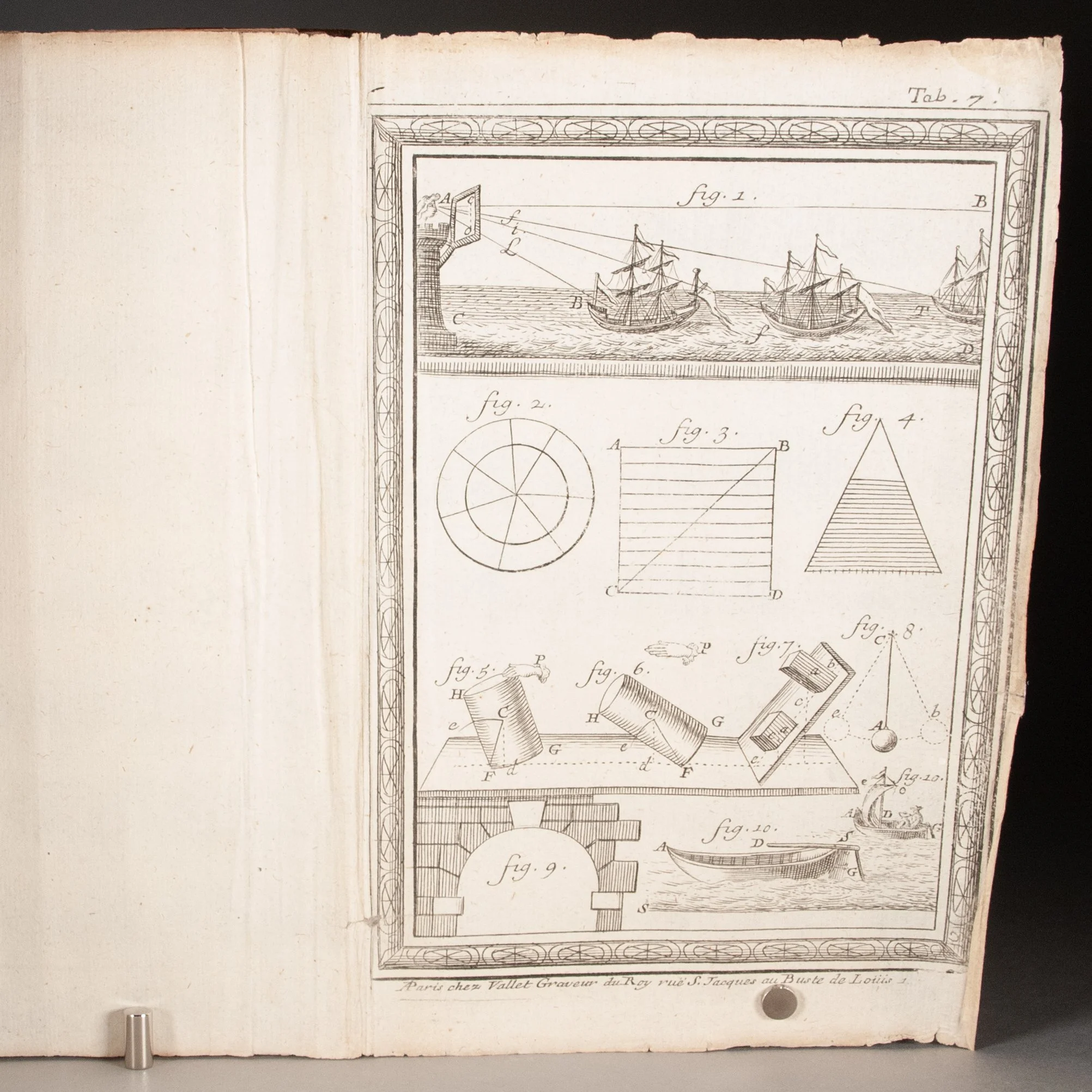

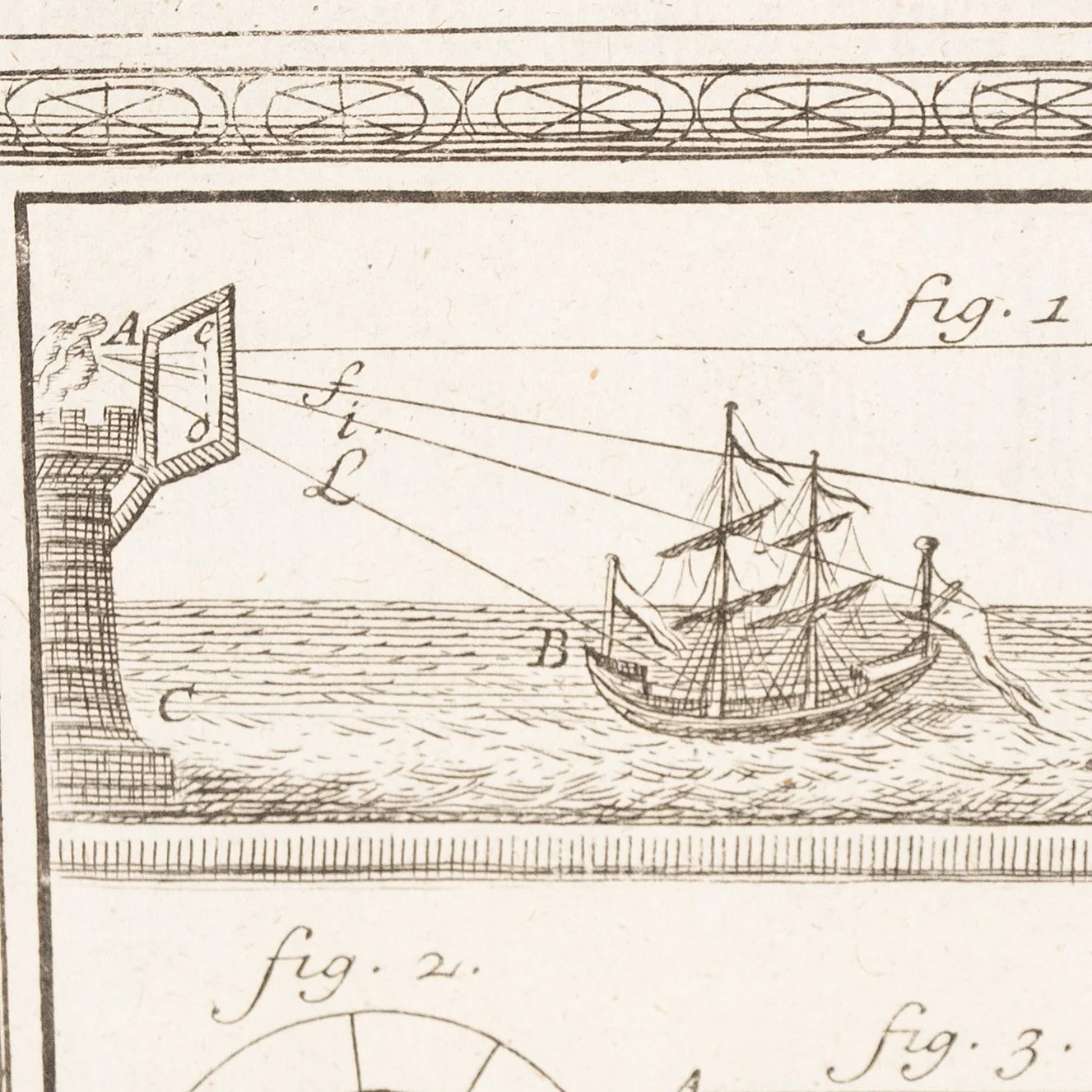

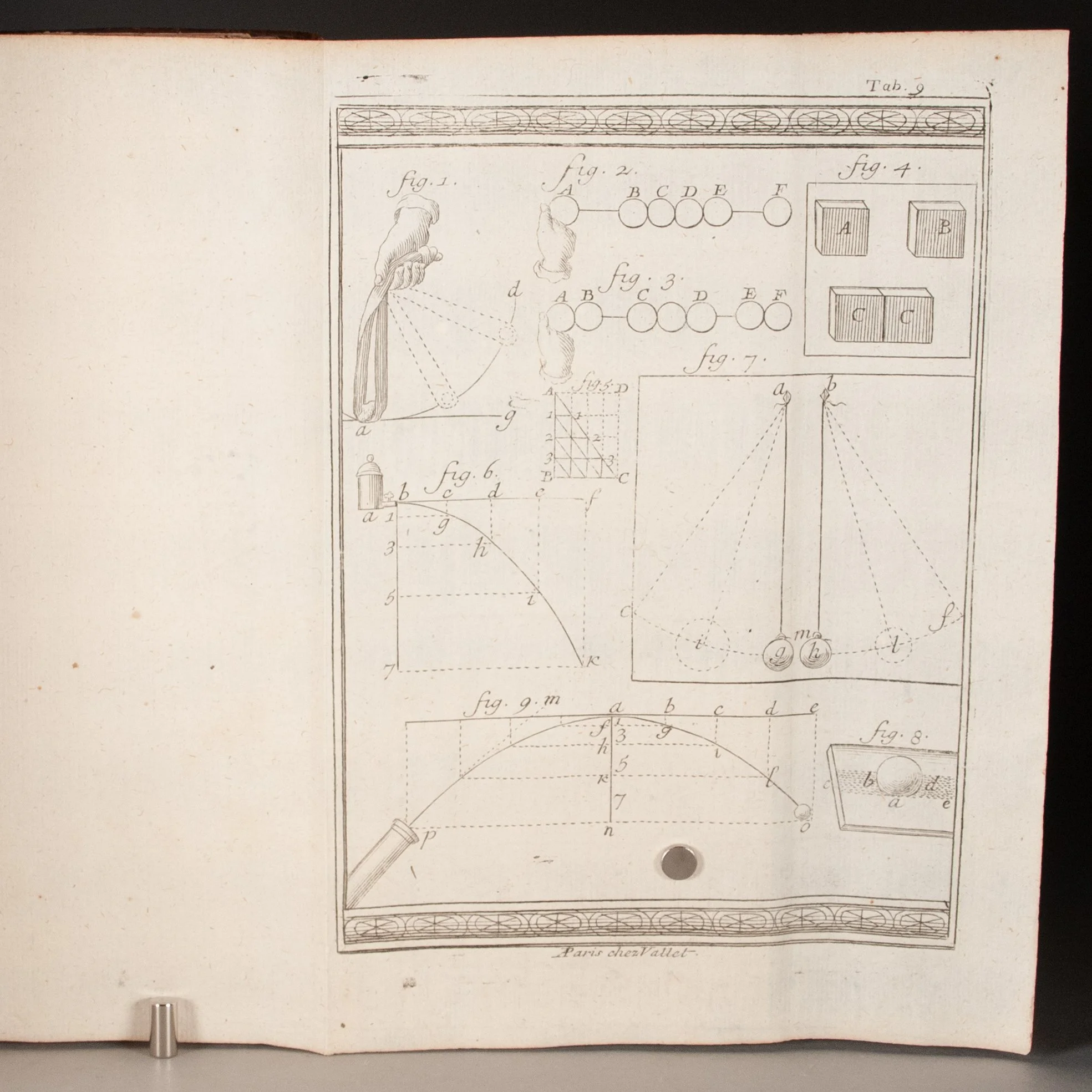

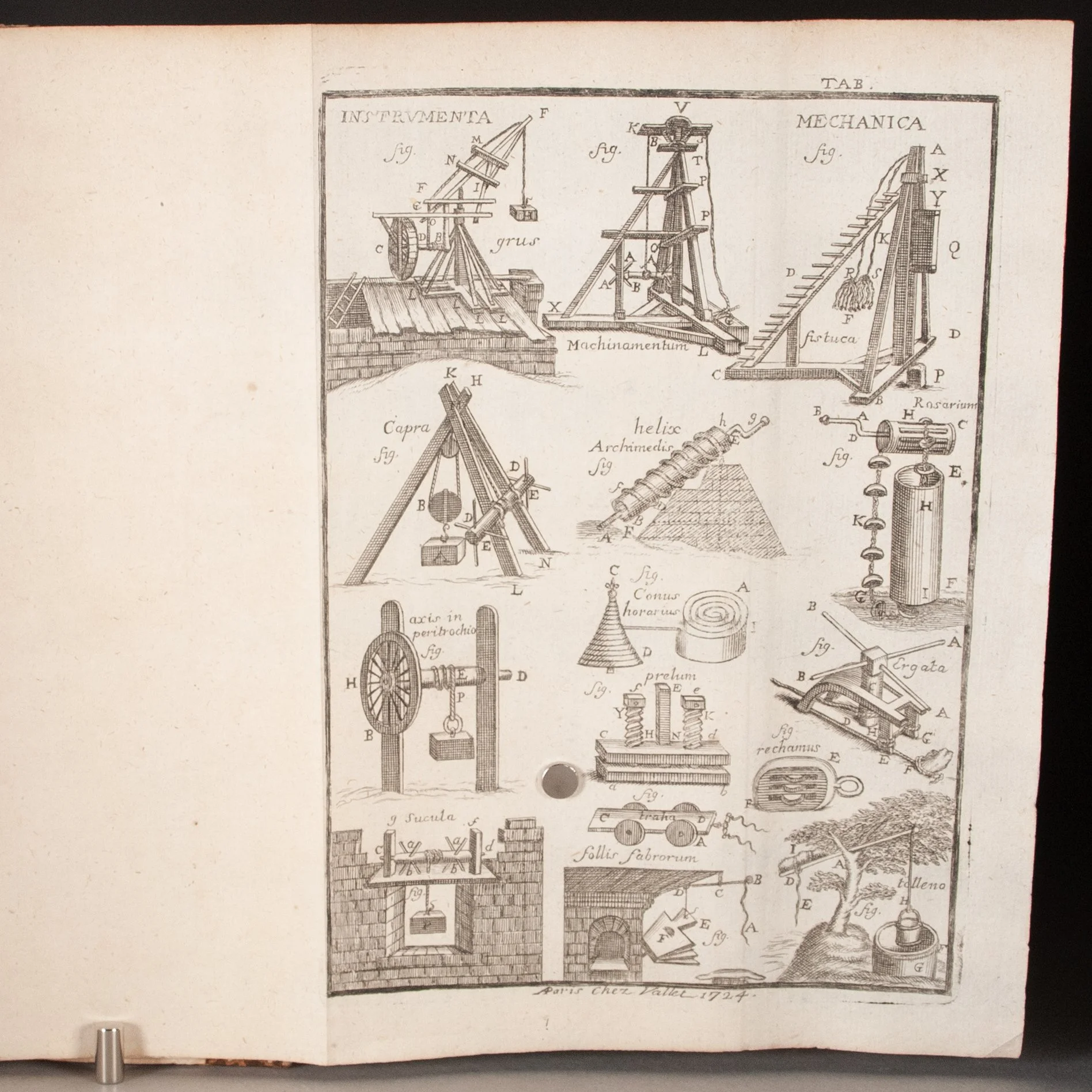

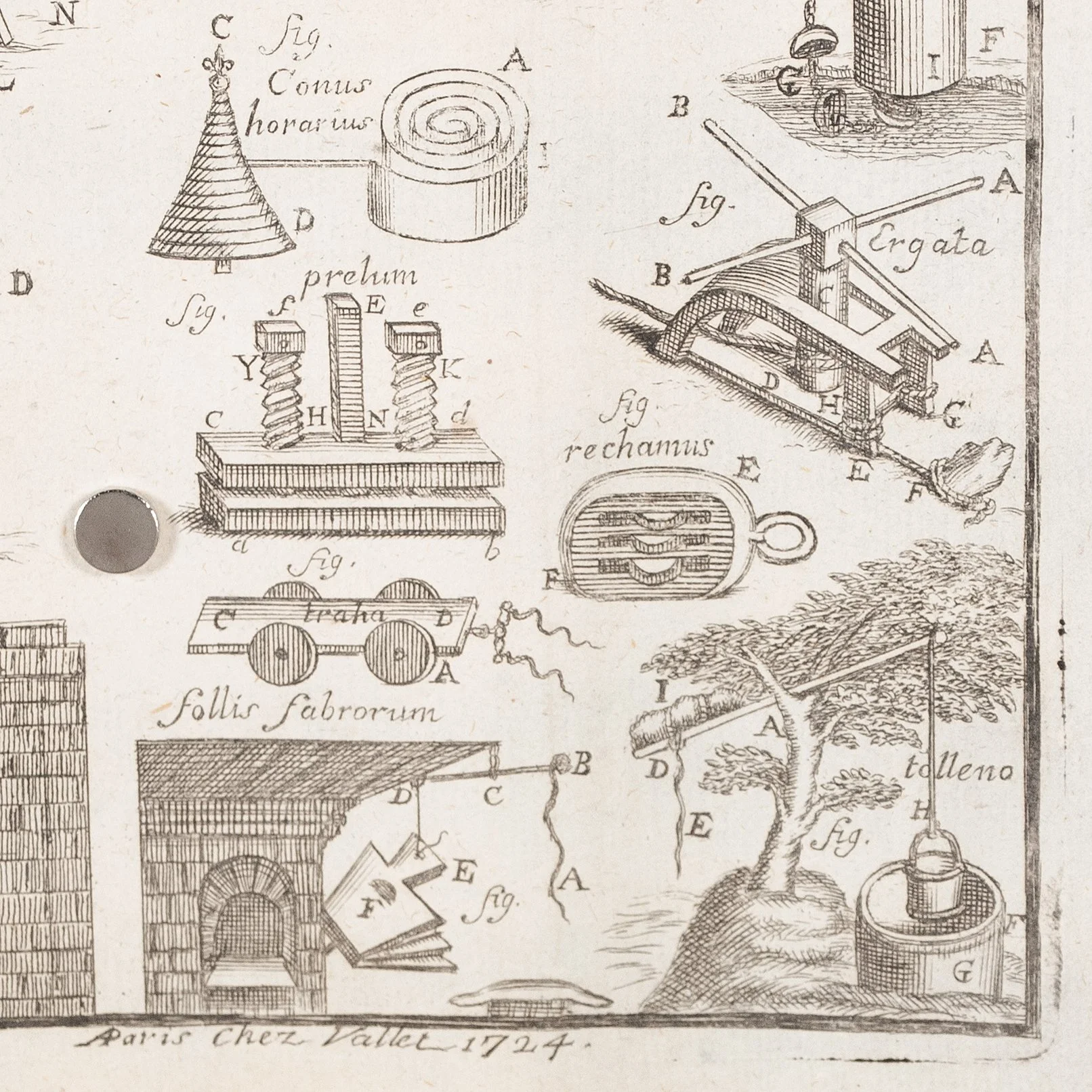

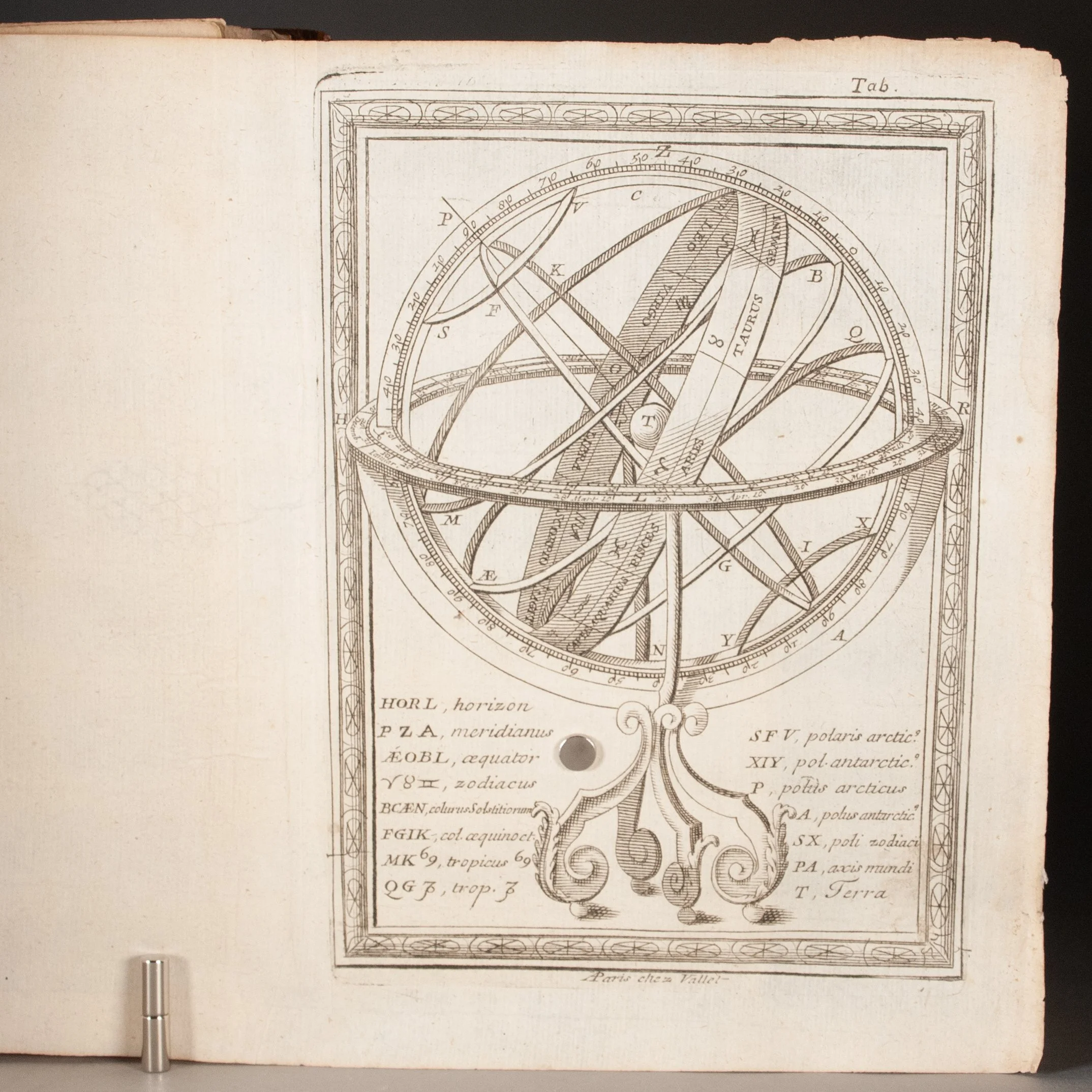

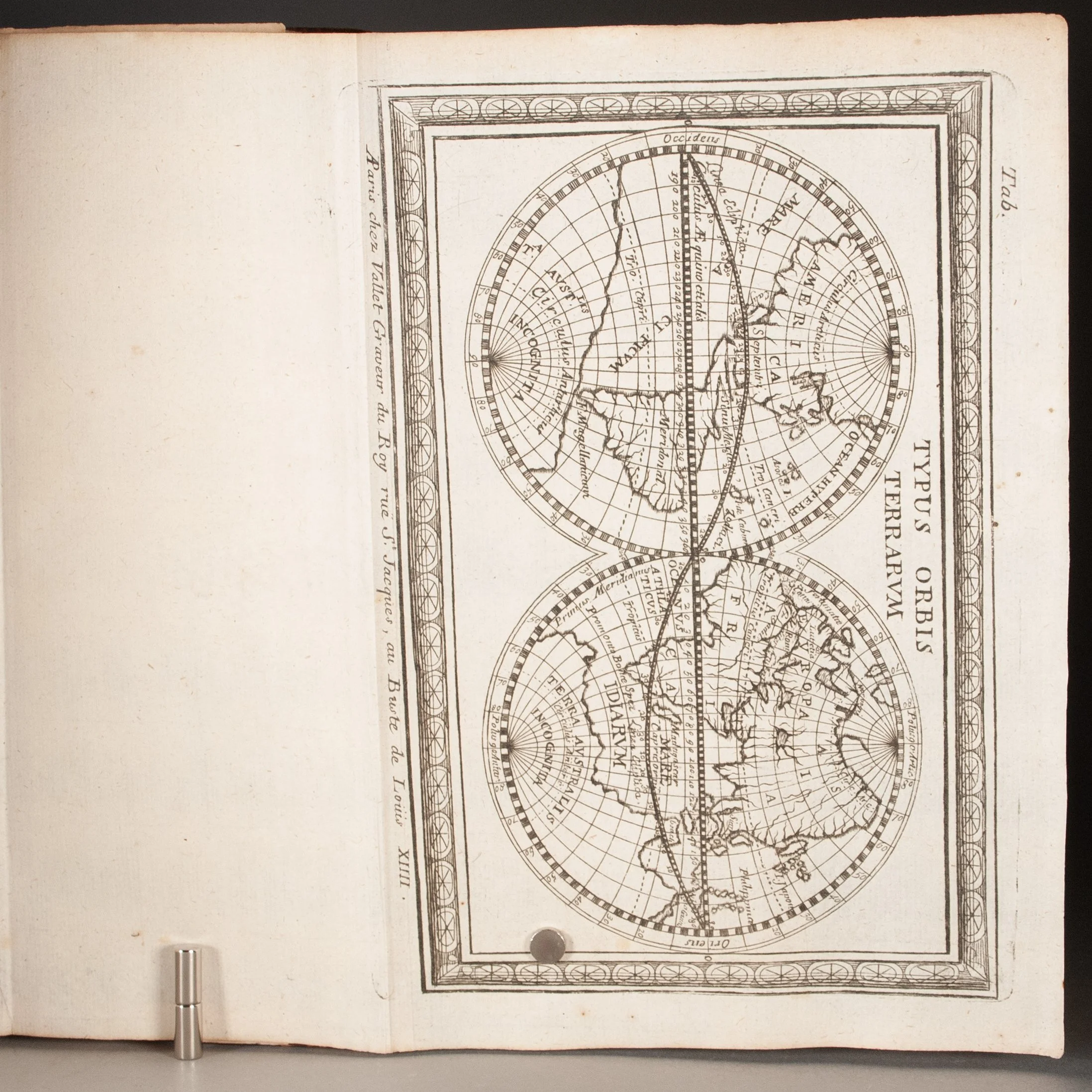

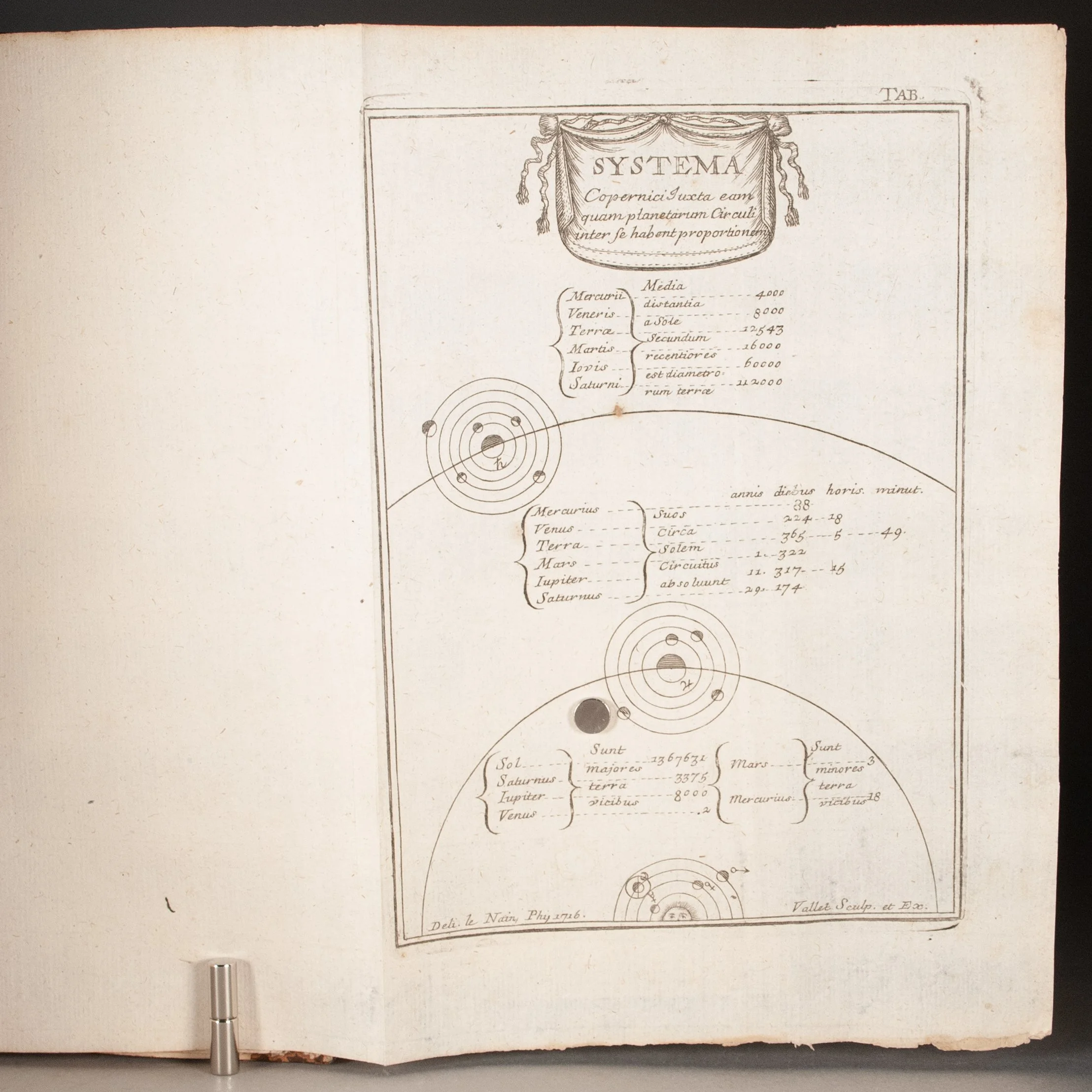

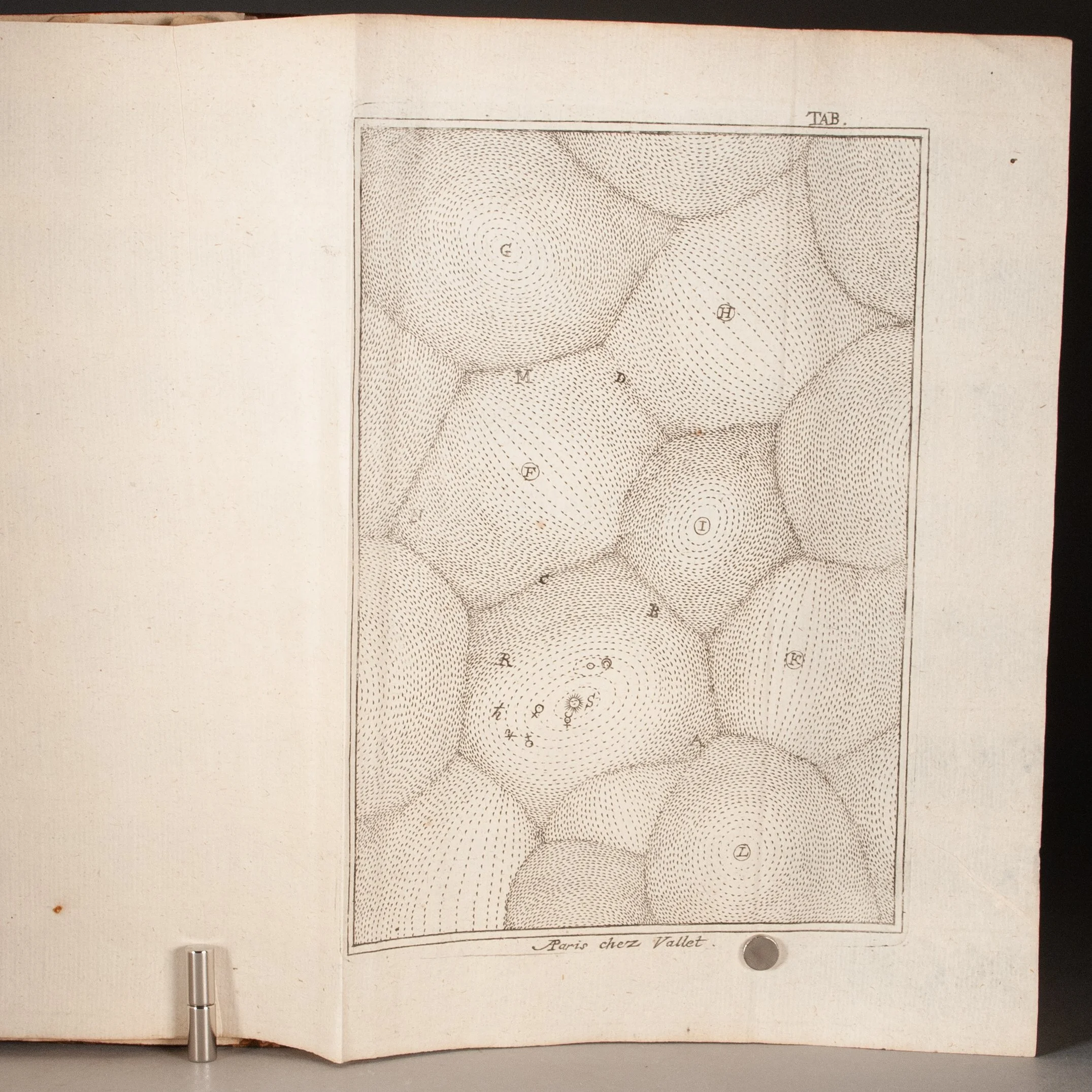

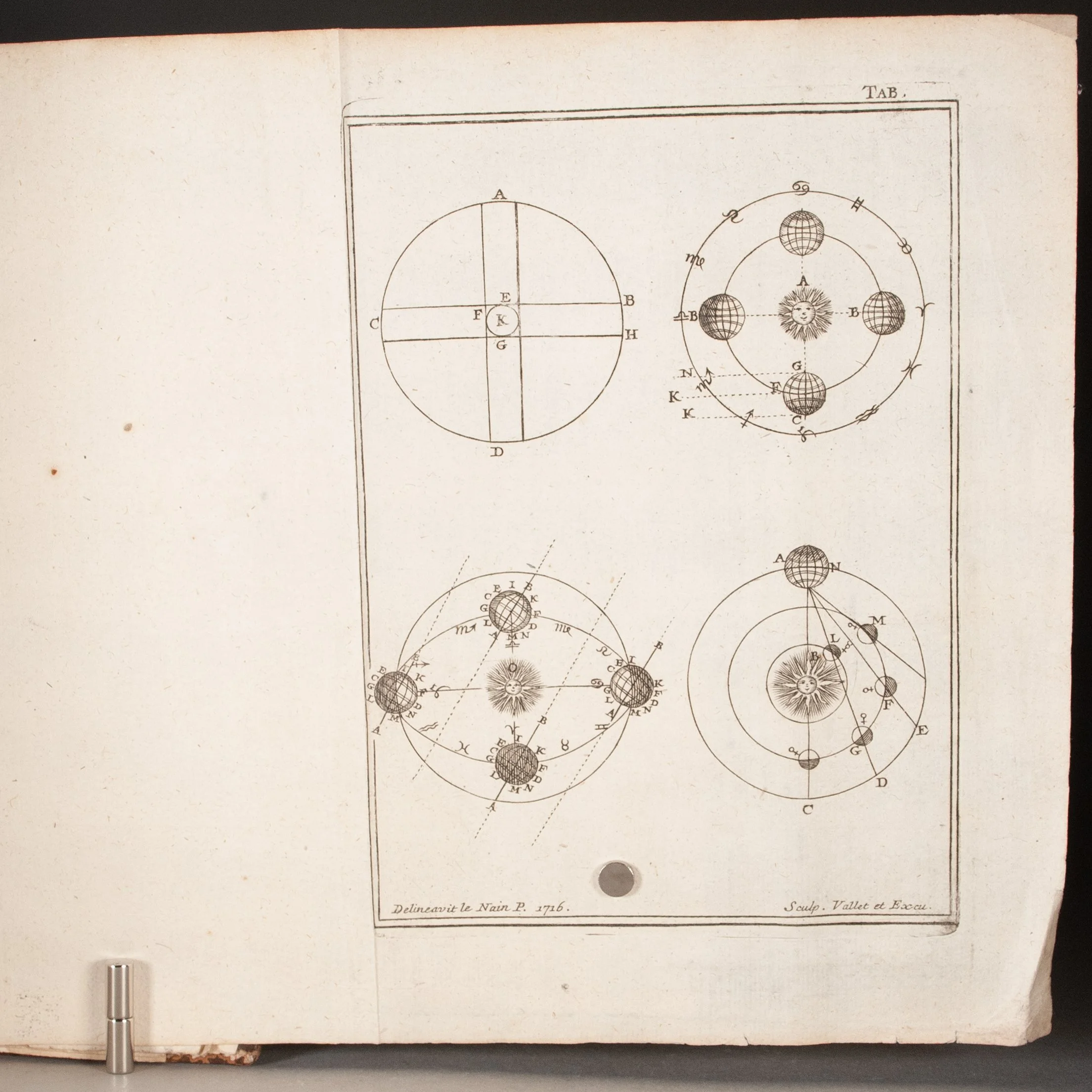

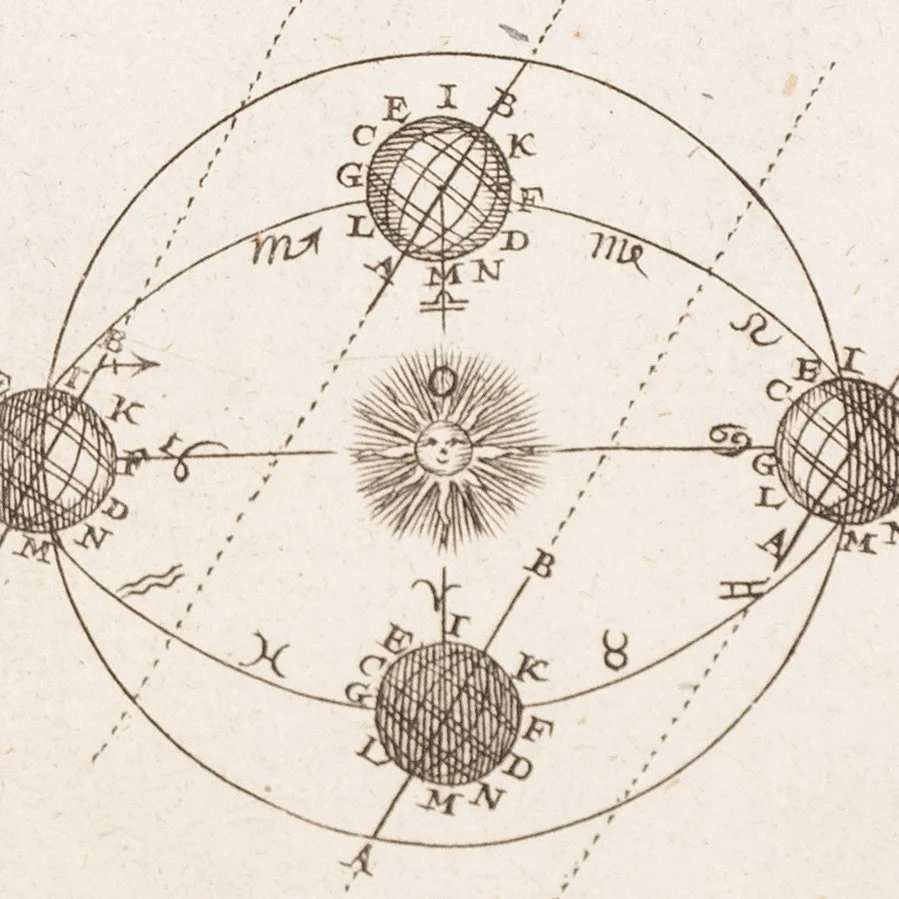

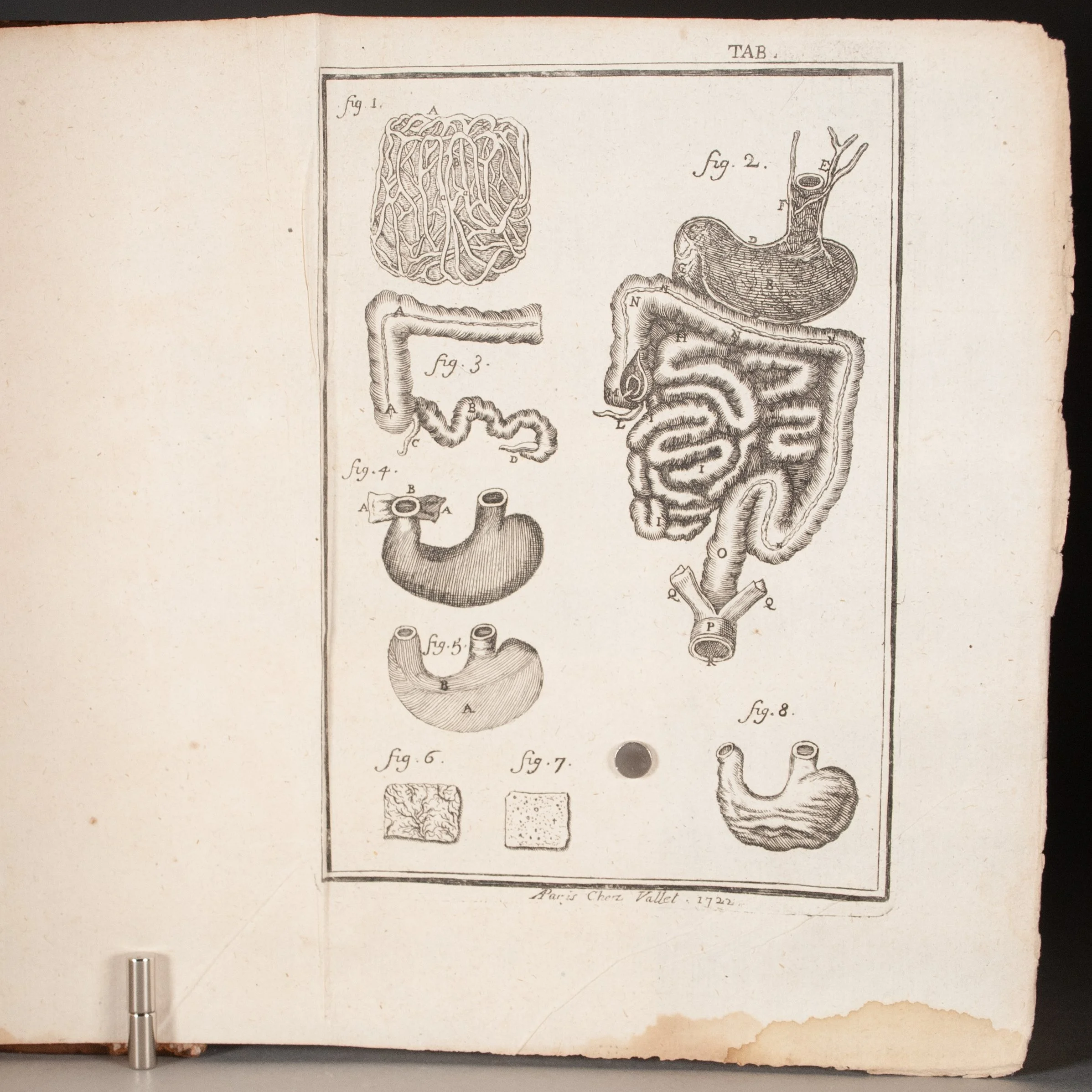

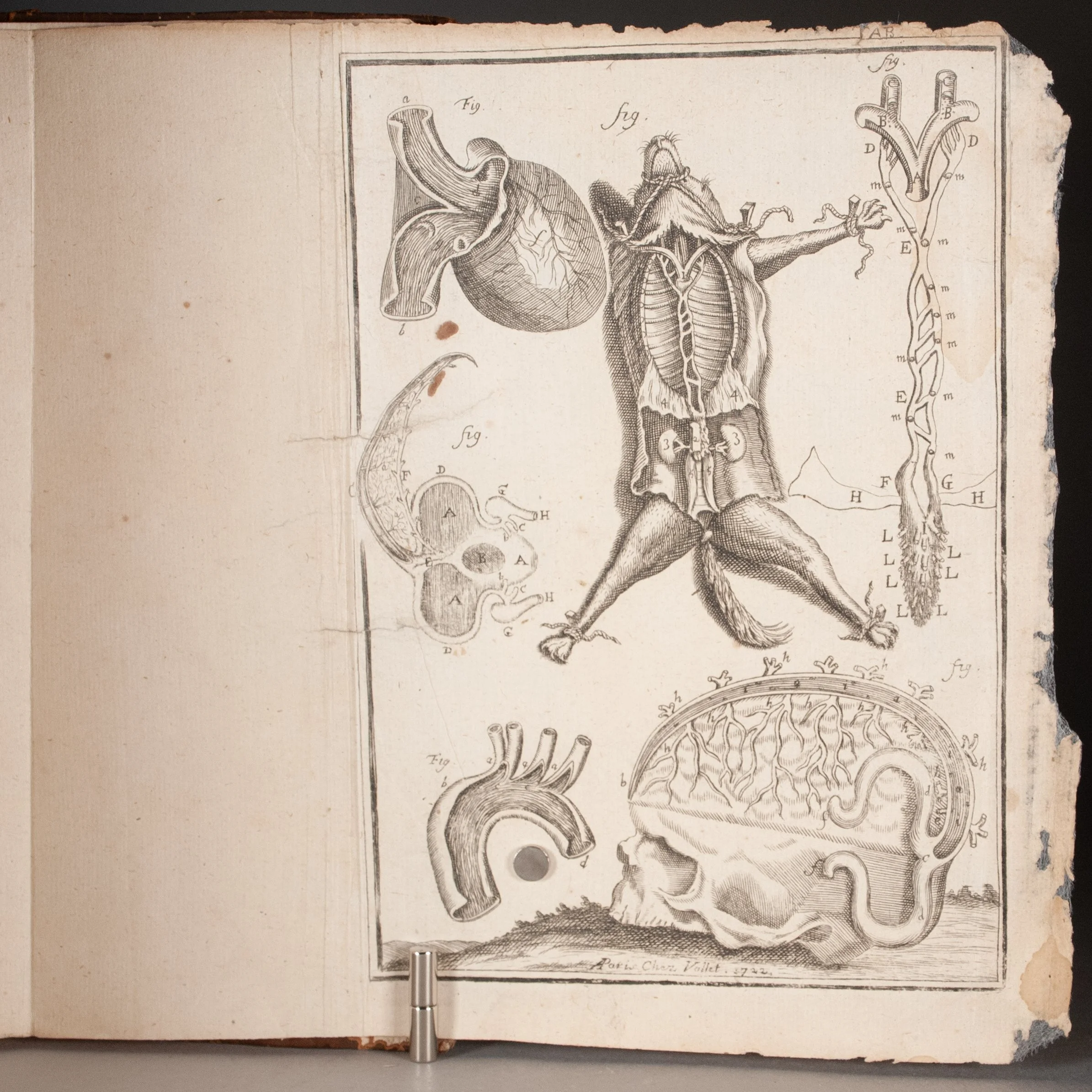

By all appearances an unpublished manuscript on physica generalis—the physical sciences broadly—very likely a student's complete university coursebook. The content ranges broadly over physics, with much on motion; it touches on gravity, air, light, optics, geology, and more; explores astronomy in particular depth (see p. 360-460 for a deep dive into the various models of the solar system, for example, including both Copernican and Tychonic systems); and even delves into the life sciences at the end. ¶ We suspect the manuscript was written by the same Jean-François-Joseph Aubert of Reims whose thesis broadside is bound in at end. His defense was to take place on 24 July 1734 at the College of Sorbonne (to which the College of Plessis was transferred in 1642, hence Sorbonae-Plessaeo at bottom). Aubert's defense moderator was François-Bruno Tandeau, Doctor of the Sorbonne and Archdeacon of Paris, and later among those tasked with reviewing Diderot's Encyclopédie for subversive content. Authorship of these printed theses is rarely clear, but scholars tend to give the edge to the senior academic over the candidate. ¶ Our combination of text and plates places the book among a group of French manuscripts of similar vintage. The Rodez municipal library, for example, has a Physica particularis et generalis with plates by Le Nain dated 1715, this perhaps the same which Pierre Costabel later described as un cours de physique. In 1901, Victor Advielle reported an 18th-century Physique expérimentale also with Le Nain/Vallet plates dated 1715-1716. To be sure, René Taton remarks that Vallet's plates were made "for the use of colleges," and adduces five additional manuscript coursebooks of similar composition—but none, we should add, with as many plates as ours. Regular readers will know we're committed fans of the combination of manuscript and print. This example does not disappoint, serving as witness to a printed series of scientific illustration specifically designed to augment manuscript coursebooks. The fundamentals of physics, engineering, biology, astronomy—Ptolemaic, Tychonic, and Copernican systems—you'll find all the greatest hits in these illustrations. ¶ The handwritten coursebook had long been a cornerstone of academic life. Students might copy the content from an instructor's dictation, copy the text from a handwritten exemplar, or even a combination of the two. Not only was the act of copying esteemed as an aid to comprehension, but the economics of print typically disfavored the production of such relatively limited press runs. "For the historian student manuscripts offer unique insight into not only the content of courses that were never published, but also the methods of teaching and learning that can be inferred from the surviving manuscripts. Of course those manuscripts cannot capture all the personal and oral interactions between teacher and students in the classroom or outside it, but they give us valuable access to the student experience that complements other sources such as official regulations and curricula and printed theses or treatises" (Blair and Goeing). ¶ Speaking of printed theses, Aubert's, folded and bound in at back, is a grand example of the genre, where we find he was tested on logic, metaphysics, morals, natural sciences, geometry, mechanics, astronomy, and geology. The enduring academic tradition of announcing thesis debates dates at least to Luther's Ninety-Five Theses, and it had become common at many European universities by the 17th century, where theses and dissertations were variously produced as pamphlets and broadsides. A few copies of such broadsheets may indeed have been posted as a public notice, but most would likely have been distributed to friends, family, and colleagues, and made available during the disputation itself as a kind of program and souvenir. It may come as no surprise that the early modern university typically did not pay for the printing of these announcements. Nonetheless, “institutional requirement aside, the degree signified such a monumental moment, and practical value, for the candidate that his family was willing to invest financial resources in printing the dissertation” (Chang). Versions like this, topped with a large engraving, were certainly on the extravagant side. The most opulent ones were wholly engraved bespoke productions now known as thesis prints. “Unfortunately, thesis broadsheets have a poor survival rate. They were often very large and their size made them awkward to store” (Pomis). True to form, we locate no other copies of this one. ¶ An illuminating relic of early modern education, illustrated with a rare suite of scientific illustration, combining two of its everyday articles—the manuscript coursebook and the broadside thesis—and demonstrating the ongoing co-utility of print and manuscript in the academic environment.

PROVENANCE: We find a Jean-François-Joseph Aubert born at Mézières in 1715, a town northwest of Reims, who seems a likely candidate for this 1734 examination.

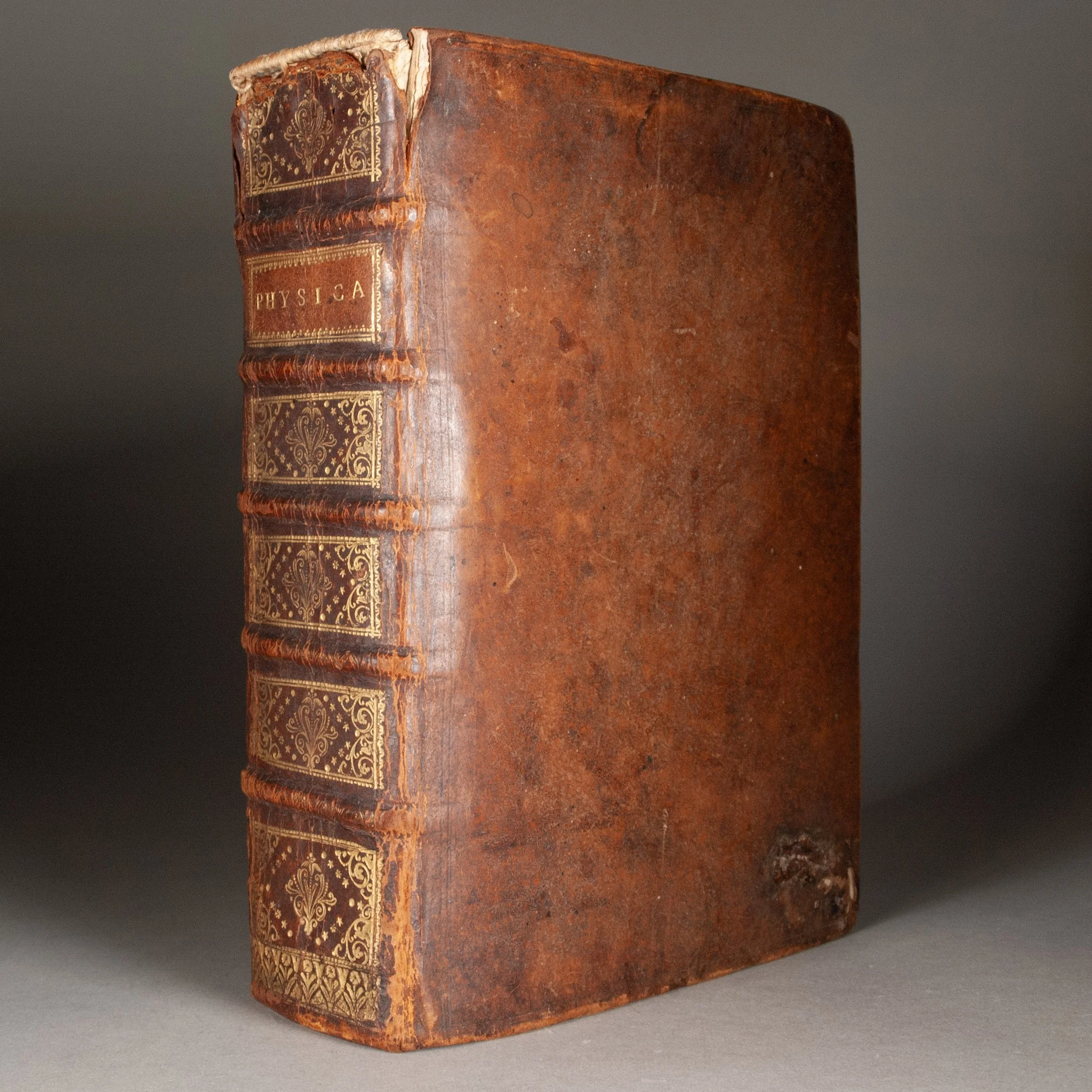

CONDITION: Contemporary brown leather, the spine tooled in gold; edges sprinkled red; marbled endpapers; silk ribbon marker. Neatly handwritten in Latin on watermarked laid paper, with a physica specialia divisional title on p. 337, and small illustration on p. 87. Last four leaves are blank. ¶ The plates predictably focus on the physical sciences, though the last two appear to venture into biology. Save for the frontispiece, all plates are bound after the thesis broadside, itself bound at the end of the manuscript. All plates appear to have been engraved and published by Vallet in Paris. With a single exception—one designed by Warel—those plates bearing a statement of responsibility were designed by "Le Nain Physicus." Many of them are dated, typically 1715 or 1716, but two dated 1722, and one each 1714 and 1724. ¶ Large 7-8" closed tear in the broadside, with a couple smaller tears in its lower margin, all expertly repaired; the final plate with some closed tears affecting the image, likewise repaired; some plates generally a bit tatty at the edges, with small marginal tears (many repaired), but nothing affecting image beyond the aforementioned final plate; two plates with a little dampstaining in the lower margin, not affecting the image; plates frequently haphazardly creased. A few scattered wormholes in the binding, more pronounced in the lower corner of the front board; headcap chipped away; both joints split along the uppermost spine compartment, but all cords intact and whole thing quite solid.

REFERENCES: On the manuscript and plates: J.M.J. Rogister, "Louis-Adrien Lepaige and the Attack on De l'esprit and the Encyclopédie in 1759," The English Historical Review 92.364 (Jul 1977), p. 536 (for Tandeau's role in Encyclopédie review); Gustavo Hainel, Catalogi Librorum Manuscriptorum qui in Bibliothecis Galliae, Helvetiae... (1830), col. 411 (the Rodez ms); Pierre Costabel, L'enseignement classique au XVIIIe siècle: collèges et universités (1986), p. 42 (cited above); Victor Advielle, Catalogue des manuscrits du 'Fonds Victor Advielle' de la Bibliothèque d'Arras (1901), p. 109, #367; René Taton, Enseignement et diffusion des sciences en France au XVIIIe siècle (1986), p. 41-42; Ann Blair and Anja-Silvia Goeing, "Manuscripts as Pedagogical Tools in the Philosophy Teaching of Jean-Robert Chouet (1642-1731)," Teaching Philosophy in Early Modern Europe: Text and Image (2021), p. 166 (cited above; "In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, manuscript academic lecture scripts were an important part of a learned written culture that included printed books, pamphlets and broadsides (e.g. theses printed for disputations or as teaching aids), and periodicals. Recent attention to the uses of manuscripts in the handpress era has shown that handwriting was preferred over print as a mode of dissemination in a variety of circumstances, notably to produce a small number of copies of lesser expense or to attempt to limit or control circulation. Manuscripts played an especially important role in academic contexts, since handwriting was (and is still) valued as an aid to retention and gave flexibility to both teachers and students in creating a record of a course."); Ann M. Blair, "The Making of Student Notes," Student Notes from Latin Europe (1400-1750): A Research Companion (2025), p. 34-35 (brief history of student note taking, dictation especially; "pedagogues throughout early modern Europe and its colonies consistently insisted that writing out a text was an essential aid to retaining it in memory—presumably this applied whether the writing was done under dictation or by copying an exemplar. Copying likely occurred now and then in courses transmitted by dictation, notably for the transmission of diagrams and drawings from teacher to students. An exemplar could be circulated on a sheet of paper or a slate; or in some cases the teacher might have had the use of a blackboard. No doubt students also copied the notes of their peers occasionally, for example, after an absence.") ¶ On the broadside thesis: Laurence Brockliss, “Printed Theses in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century France,” Early Modern Disputations and Dissertations in an Interdisciplinary and European Context (Brill, 2021), p. 198-199 (“Few theses, furthermore, even those published in-folio, were embellished with an engraved illustration, especially one specifically created for the occasion. Adding a picture to a printed set of theses would have greatly inflated the cost…Even the more complex designs were not normally bespoke”); Louise Rice, “Pomis sua nomina servant: The Emblematic Thesis Prints of the Roman Seminary,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 70 (2007), p. 197; Ku-ming (Kevin) Chang, "For the Love of the Truth: The Dissertation as a Genre of Scholarly Publication in Early Modern Europe," KNOW: A Journal on the Formation of Knowledge 5.1 (Spring 2021), p. 114, 130, 125 (the term thesis print has come to describe the especially lavish, often wholly engraved broadside prints; a “copy of the engraved broadside was placed at the focal center of the auditorium during the solemn disputation…Engraved thesis prints were common in Catholic countries.”), 133-135 (focusing on pamphlet theses: “The printed dissertation was a commissioned publication…The candidate received the printed copies of the dissertations before the disputation and then submitted a number of copies to certain offices and persons as regulated by his university…Then the student sent copies to opponents appointed to his disputation, other professors or private lecturers at the university, and his family members, patrons, fellow students, and friends. He probably also provided free copies to the audience of the disputation. The actual print run varied from one university to another…Generally speaking, in eighteenth-century Germany, 200 copies were considered sufficient, and 300 abundant.”); Louise Rice, “Jesuit Thesis Prints and the Festive Academic Defence at the Collegio Romano,” The Jesuits (University of Toronto, 1999), p. 148 (“It was in the colleges run by the Jesuits for the education of noble boys that the thesis print first emerged as a distinctive category of engraved image. The vogue quickly spread to the universities and other institutions of higher education…Popular throughout Catholic Europe from the beginning of the seventeenth century through the third quarter of the eighteenth, the thesis print fell out of fashion around the time the Society itself was suppressed in 1773.”), 149 (because the time and place typically appeared on these, “it is sometimes assumed that the broadsheet functioned primarily as a kind of advertisement, announcing the event in advance and inviting attendance. But although it may have been common practice to post one or two copies of the sheet ahead of time, publicity was not its primary purpose. Rather, the booklet or sheet was distributed to the members of the audience during the defence itself; it served as a kind of program, which enabled the audience to follow the progress of the disputation, and was taken home as a record or souvenir of the event.”)

Item #794