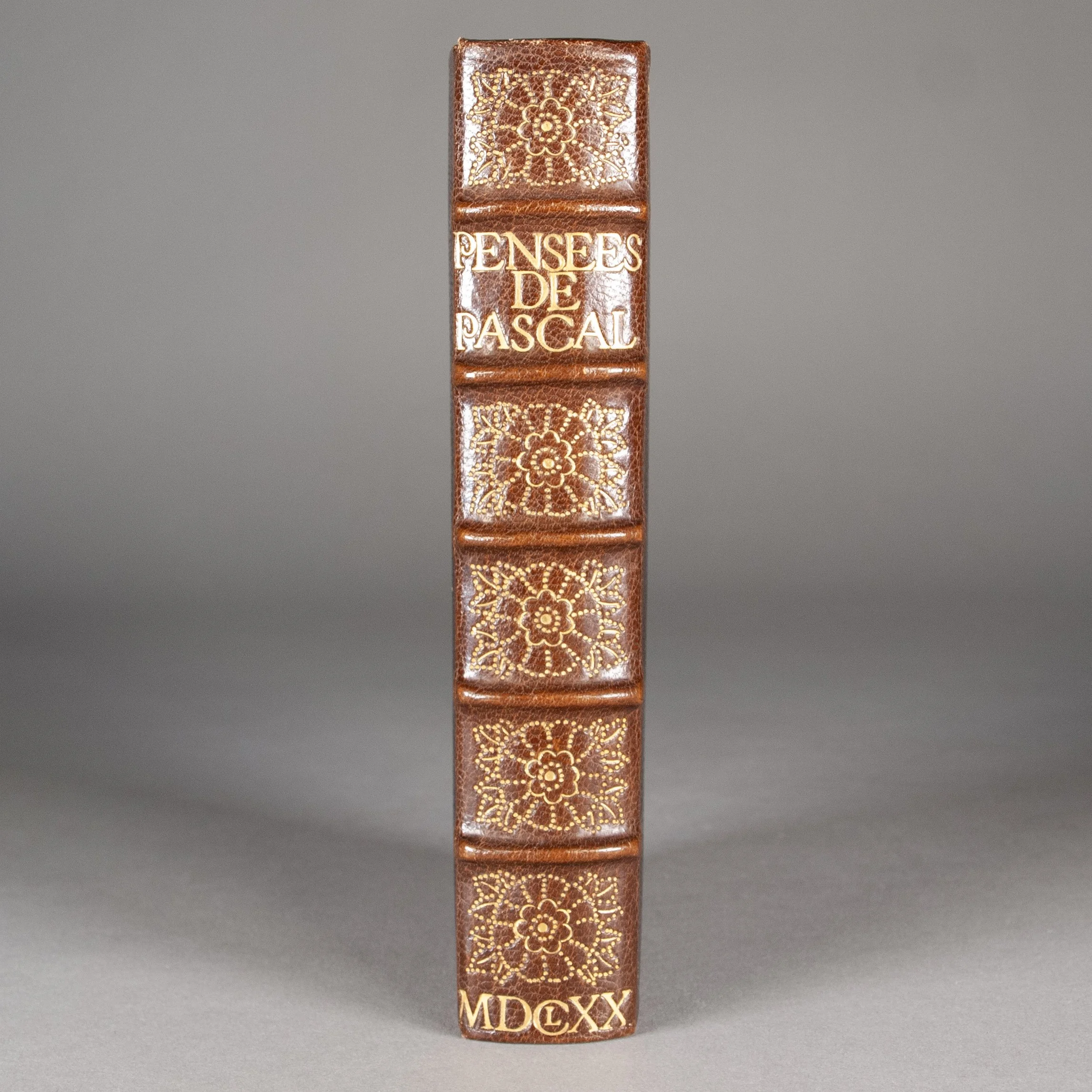

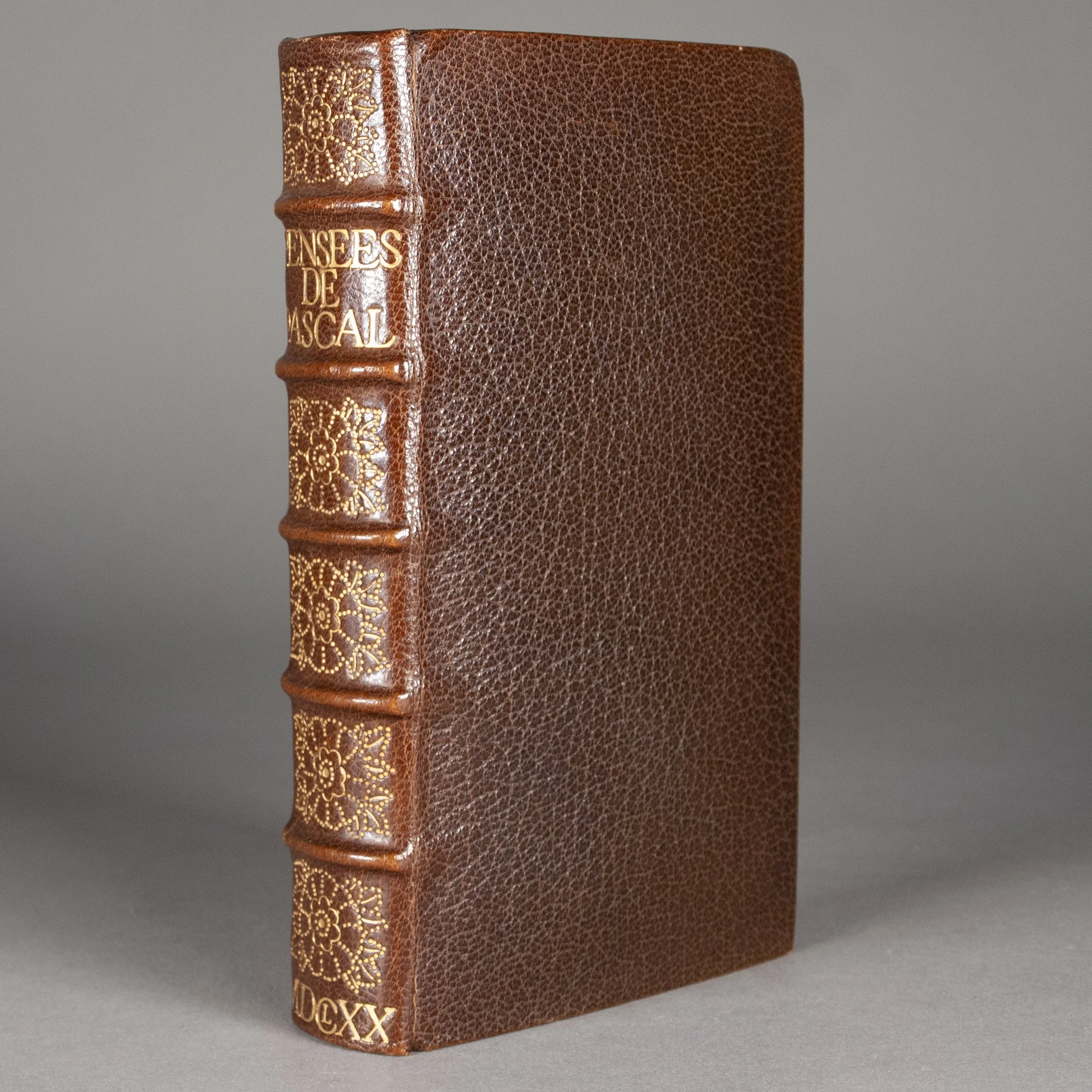

Early Katharine Adams binding for St. John Hornby

Early Katharine Adams binding for St. John Hornby

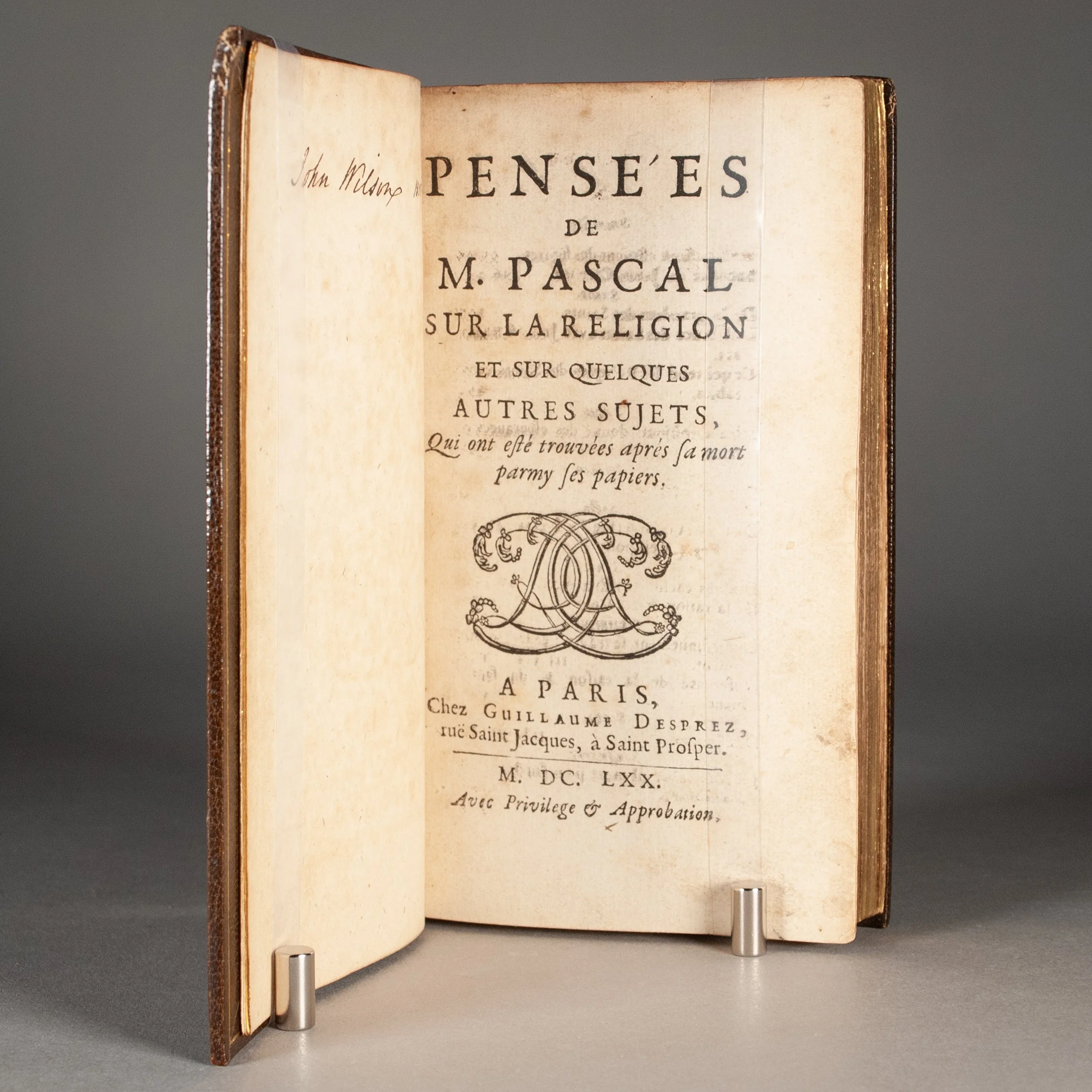

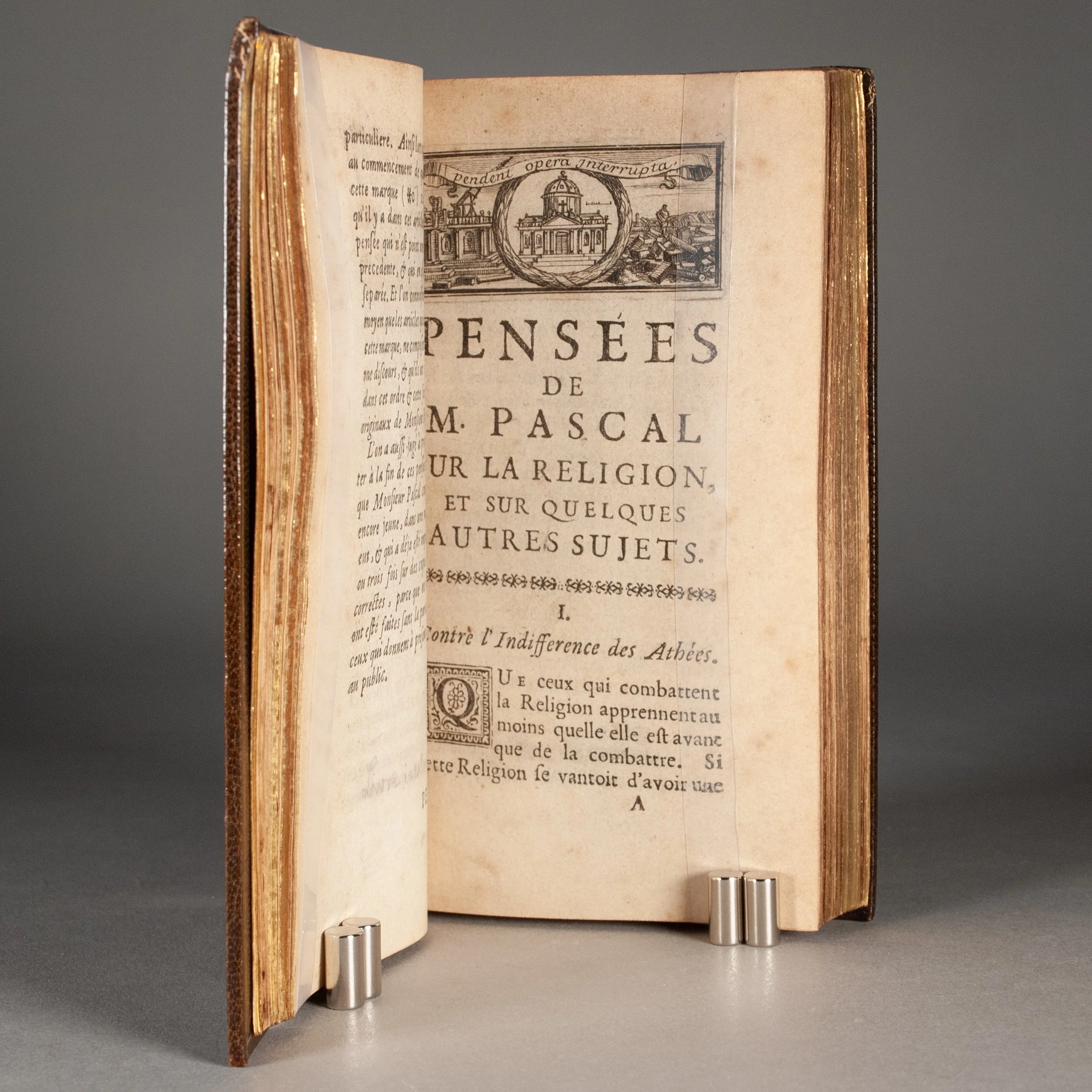

Pensées de M. Pascal sur la religion et sur quelques autres sujets, qui ont esté trouvées après sa mort parmy ses papiers

by Blaise Pascal

Paris: Guillaume Desprez, 1670

[80], 312, 307-330, 313-334, [20] p. | 12mo | ã^8 ē^4 ĩ^8 õ^4 ũ^8 ãã^4 ēē^4 A-Gg^8/4 Hh^8 Ii1 | 153 x 87 mm

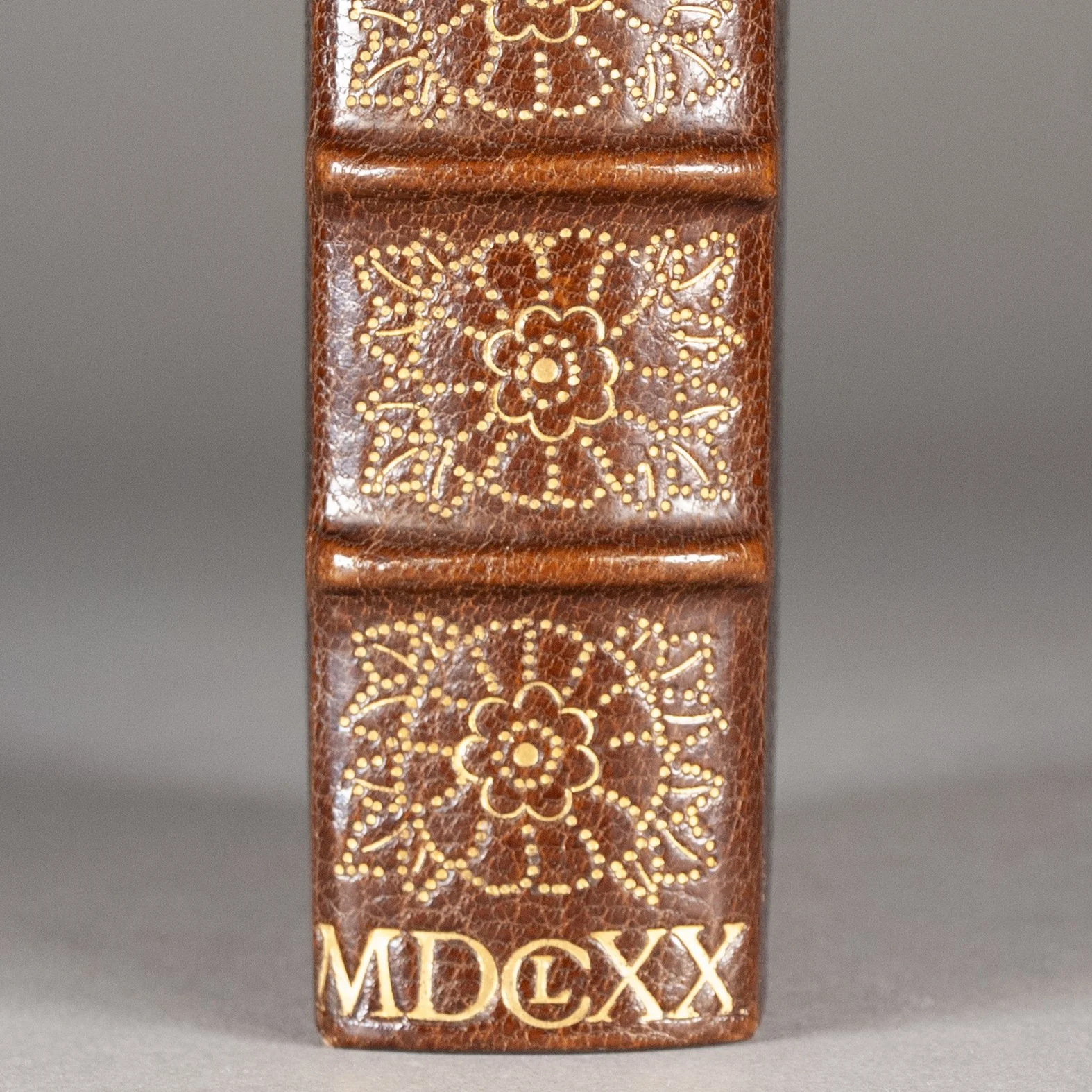

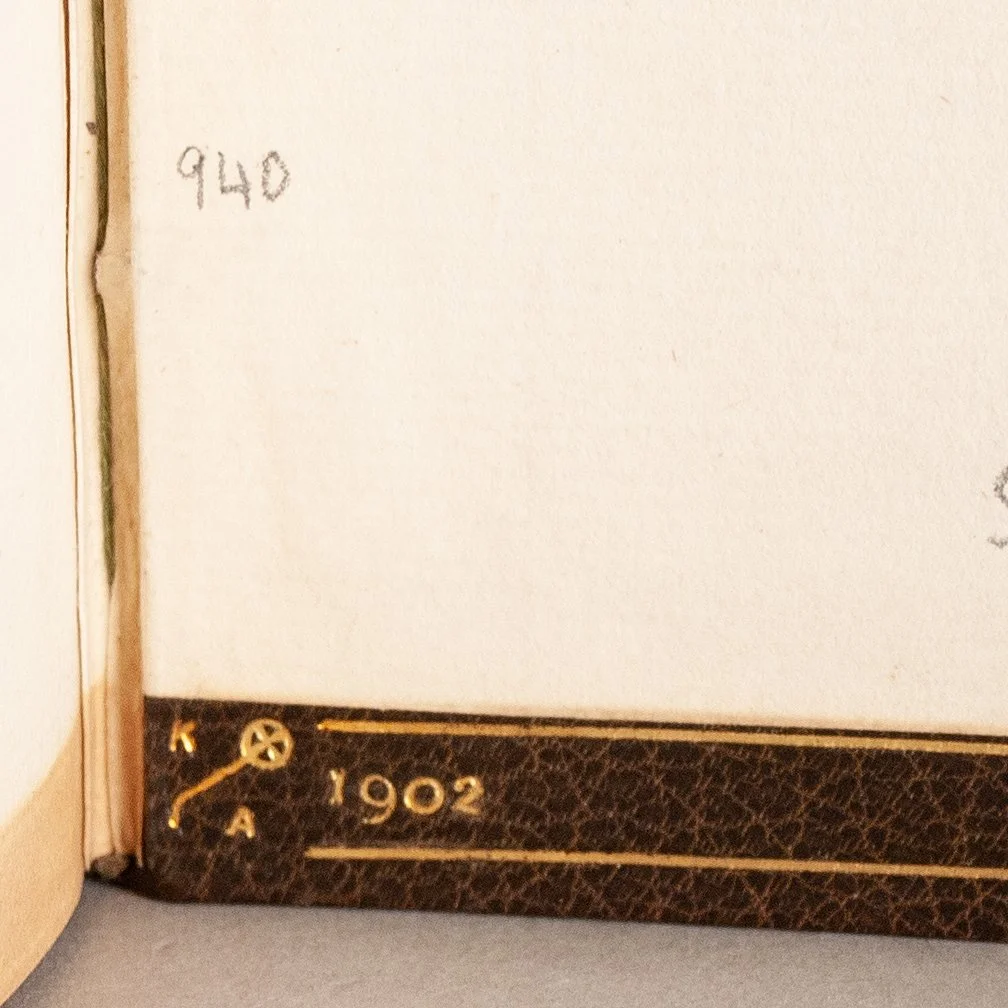

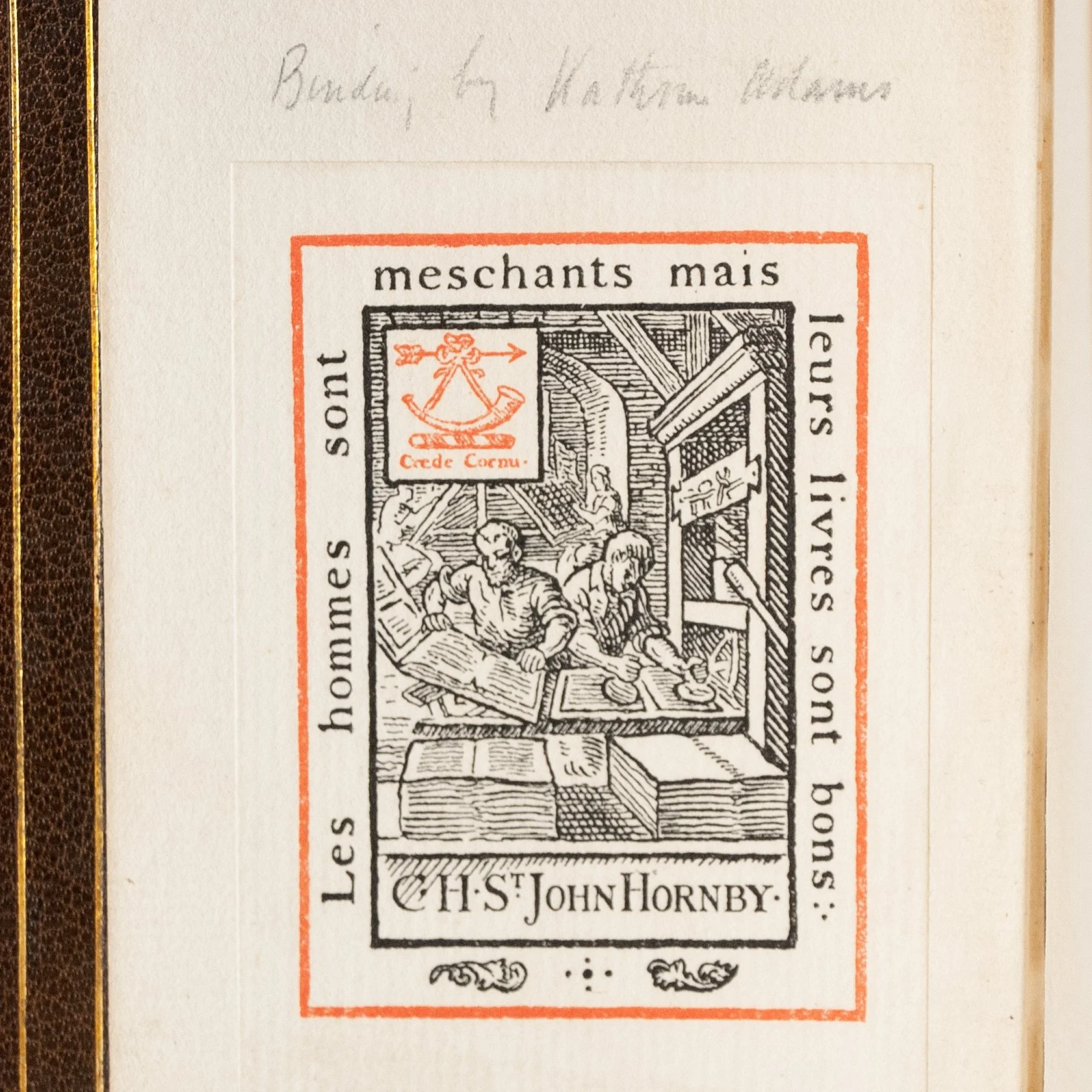

First issue of the second edition (sometimes called the second printing) of Pascal's Pensèes, a massively influential landmark of Western thought by the French mathematician, scientist, and philosopher. Lauded for its timeless assessment of the human condition, acclaimed by many for its modernist flavors, and widely acknowledged as the author's masterpiece—truly something given the litany of his accomplishments—the work has endured as a cultural touchstone since it first appeared more than three and a half centuries ago. "Were it possible to summarize Pascal's action in the seventeenth century in one word, it should be 'subversive.' Like nobody else in the period, Pascal absorbed the modern intellectual trends of the time—many of which were secularizing—in order to subvert and utilize them in favor of a doctrine that Pascal himself characterizes as the most shocking to our reason" (Neto). ¶ The book is a posthumously published collection of fragments that Pascal left unfinished. Scholars have long debated their rightful order, even their intended purpose, but it's clear that Pascal had earmarked many of these pensées (or thoughts) for a larger defense of Christianity. Discovered among his papers after this death, they were ushered through publication—though not without modification—by a coterie of Jansenist friends, who attempted to place them in some kind of logical arrangement (and avoid courting controversy, which seemed to follow the Jansenist movement like a shadow). To call his Pensées a pioneering Christian apology hardly does it justice. While the book has an undeniably religious aim—to convince skeptics they should believe in God—its method is deeply philosophical. Pascal refrains from bombarding his readers with doctrine and dogma, but meets them on their own skeptical ground. Perhaps his most famous tactic—which has proved a significant contribution to the theory of probability—has come to be known as "Pascal's wager," wherein he simply argues that the potential benefits of believing in God (life everlasting, at the relatively low cost of foregoing modest indulgences) far outweigh those of not (eternal torture in hell). "The enduring value of the Pascal's Wager," Joel Hodge observes, "is that, bypassing intractable debates over God's existence, it brings the question of God into a practical, existential focus." ¶ The wager is only the start. William D. Wood argues for Pascal's place among the pantheon of moral philosophers. Graeme Hunter finds in the Pensées a modern approach to addressing the libertine restlessness of Pascal's age. To be sure, the book's ability to engender thoughtful reflection and debate—decade after decade, century after century—must be among its greatest accomplishments. "Certain books seem destined to help each generation determine its own place in history. We identify and characterize separate epochs of history in large part by watching each of them react to the same texts in different ways. In this sense Blaise Pascal's Pensées has played and continues to play an extraordinarily generative role in the Western tradition, with each succeeding generation defining itself and its place in history be responding to Pascal's sharp characterization of the human condition. Neither age nor custom seems able to stale Pascal's infinite variety" (Meskin). ¶ That Pascal could produce a work of such breadth of mind is hardly surprising, given the variety of his contributions to western knowledge. He was an accomplished mathematician and physicist, making important contributions to the theory of probability—a field he is said to have co-founded—and to our understanding of vacuums. He built a calculating machine as a teenager, conducted the first experiment to correlate altitude with atmospheric pressure, is frequently credited with inventing the hydraulic press and the syringe, and even the first public transportation system. "Pascal is by no means a one-work celebrity," that much is clear, "but the Pensées at once crown and illuminate the rest of his life and work" (Krailsheimer). ¶ And in a Katharine Adams binding no less, signed with her KA device and dated 1902. It's a model example of her work, showcasing her iconic pointillé technique to fill the spine compartments (accented with small gouges), then lettered in her characteristically bold, graceful style. Marianne Tidcombe placed Adams among "the three most famous women binders of the period"—1880-1920, namely the Arts and Crafts period—along with Sarah Prideaux and Sybil Pye. Adams developed an interest in bookbinding even as a child, but did not pursue it deliberately until she found herself in need of money in her thirties. She trained in 1897 with Sarah Prideaux, a month with Douglas Cockerell—all she could afford—then came her first commission, from Mrs. William Morris. In 1901, she established her Eadburgha Bindery in Gloucestershire—placing ours among her earliest bindings—where she worked until 1915. "In the years leading up to the First World War, Katharine Adams did much of her best work in this workshop. She worked alongside two girls whom she trained: Jessie Gregory, who assisted with the sewing and the needlework when necessary, and Georgina Hampshire, who helped with the forwarding" (Tidcombe). She did some work for the book trade, but largely benefited from the patronage of private collectors, who recognized her exceptional craftsmanship and strong aesthetic judgment. "She gradually built up a reputation for sound plain binding, and restrained tasteful designs," producing work for the likes of Emery Walker, Sydney Cockerell, St. John Hornby (like our example), C.W. Dyson Perrins, and Charles Fairfax Murray. Walker told Perrins that his set of the Doves Bible, which Adams had bound, was "one of the very best specimens of tooled binding since the great age—the sixteenth century" (Maggs). The war brought a move near Oxford, when her paid work slowed significantly, though she continued to exhibit. Tidcombe estimates her lifetime output at some 300 bindings.

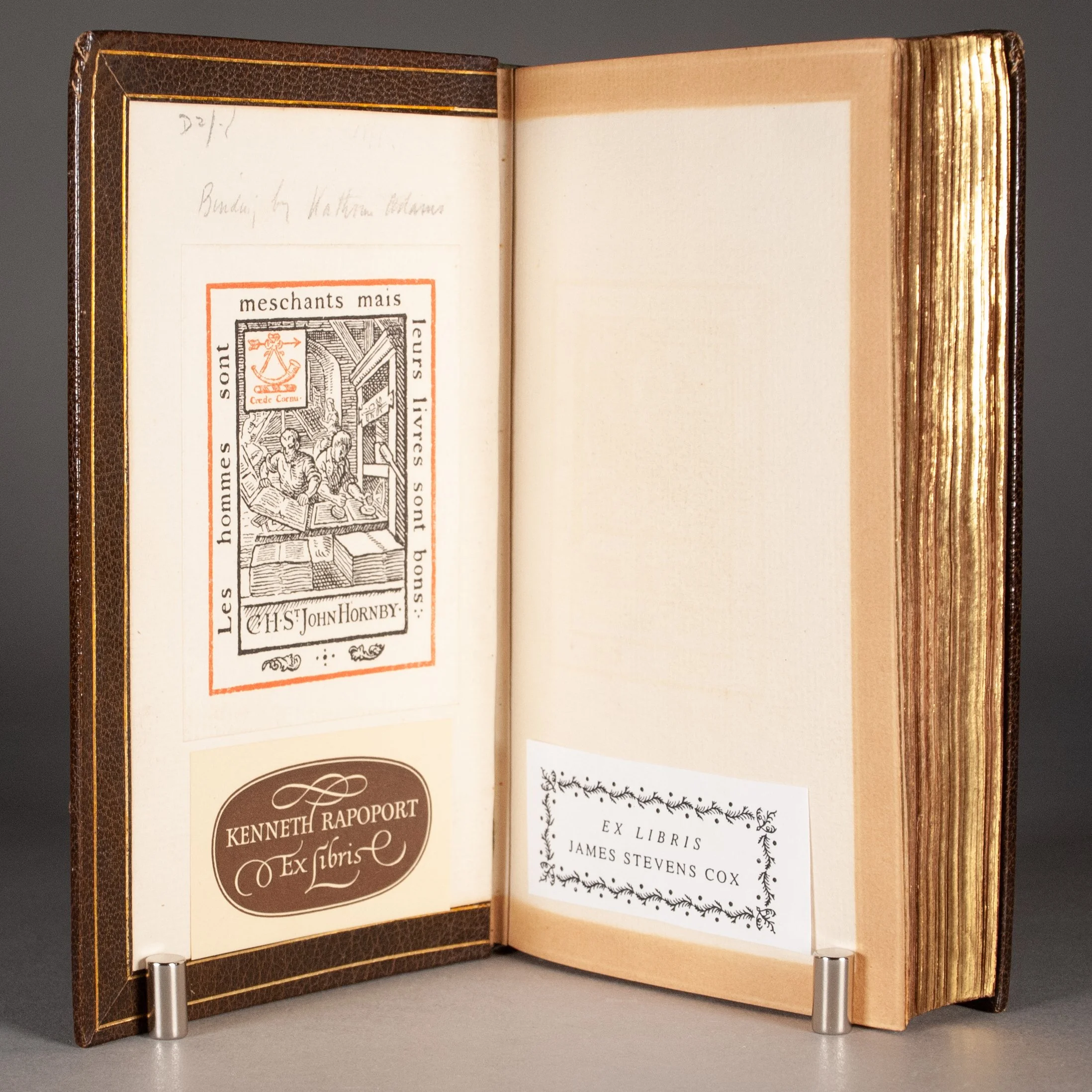

PROVENANCE: A copy with impeccable Arts and Crafts provenance, bearing the bookplate of C.H. St. John Hornby, founder of the Ashendene Press, one of Adams's earliest and most loyal clients. With subsequent bookplates of collectors Kenneth Rapoport and James Stevens Cox. ¶ Occasional penciled markings, including a brief penciled English annotation at the foot of p. 37. Ownership signature of John Wilson, 1815, on fly-leaf facing title.

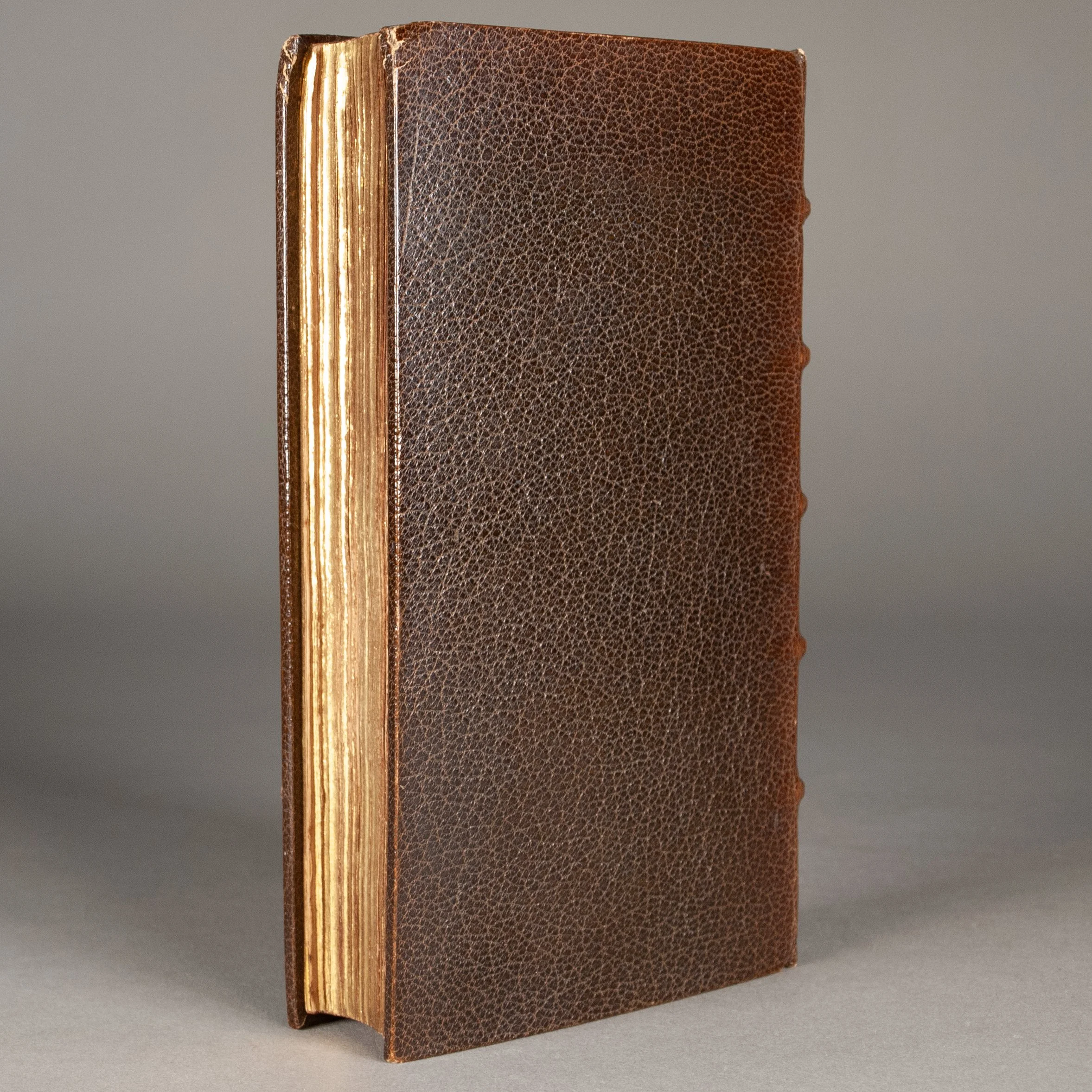

CONDITION: Bound in brown morocco by Katharine Adams, as described above; all edges gilt. First issue of the second edition, the edition marked by the particular pagination errors, and the issue by the absence of an edition statement on the title page (added to the title in the subsequent issue). With the publisher's cipher on the title, and a few decorative initials and head-pieces, including a charming etched head-piece on p. 1. Faint offset image of p. 47 on title verso. ¶ Mildly soiled and foxed throughout; very discreet 5 mm closed tear in fore-edge of Bb8, nowhere near the text. Top corners a trifle bumped, the spine almost imperceptibly sunned, the binding truly in excellent condition.

REFERENCES: USTC 6125492; Albert Maire, Pascal philosophe: Les pensées; éditions originales, réimpressions successives (1926), p. 107, #8 (citing the second issue with seconde édition on title); Tchermerzine, Bibliographie d'éditions originales et rares d'auteurs français (1933), v. 9, p. 73 ¶ Printing and the Mind of Man (1967), p. 90, #152 ("Pascal's work has, in fact, the marks of genius, exploring and stating all that can be said on both sides of the question it investigates...This is not a book which one can measure as a totality in terms of orthodoxy or the reverse. It is, however, a book for which the enquiring mind has had solid reason to be grateful from its first imperfect publication to the present day."); José R. Maia Neto, "Blaise Pascal," The Columbia History of Western Philosophy (1999), p. 357 (cited above); William D. Wood, "Axiology, Self-Deception, and Moral Wrongdoing in Blaise Pascal's Pensées," The Journal of Religious Ethics 37.2 (Jun 2009), p. 356 ("Pascal is much more than a religious moralist with a fine prose style. He is also an important moral philosopher, one who deserves a place alongside the other, more systematic, ethicists of the early modern pantheon."); Graeme Hunter, "Motion and Rest in the Pensées: A Note on Pascal's Modernism," International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 47.2 (Apr 2000), p. 91 ("The wager is of course one of the justly celebrated contributions of the Pensées, and it is also one of its distinctly modern features, the science of probability having been born with, and in part through, the Pensées"); Joel Hodge, "Pascal's Wager Today: Belief and the Gift of Existence," New Blackfriars 95.1060 (Nov 2014), p. 698 (cited above); Jacob Meskin, "Secular Self-Confidence, Postmodernism, and Beyond: Recovering the Religious Dimension of Pascal's Pensées," The Journal of Religion 75.4 (Oct 1995), p. 487 (cited above); E.B.O. Borgerhoff, "The Reality of Pascal: The Pensées as Rhetoric," The Sewanee Review 65.1 (Jan-Mar 1957), p. 15-16 (on the original state of Pascal's fragments: "Pascal had made up a number of bundles obviously destined for a work of Christian apologetics he had been preparing; there was in addition a bundle of notes for a treatise on miracles; but there was also a considerable mass of unclassified papers"); John Cruickshank, "Pascal, Blaise," The New Oxford Companion to Literature in French (2005; "There is no doubt that Pascal's greatest work remains the Pensées," which "use an analysis of the problem of human nature in order to interest the reader in the Christian solution"); A.J. Krailsheimer, "Introduction," (1984), 11 (cited above); Marianne Tidcombe, Women Bookbinders 1880-1920 (1996), p. 6 (cited above), 132 ("generally the beauty of her bindings depends on the effect of gold-tooling and lettering and leather"), 134 (cited above), 143/146 ("all the leather she used, with the exception of the native-dyed niger goatskin, was prepared according to the Society of Arts specifications. This meant the leather was supposed to be free from the injurious acids that caused the decay of so many 19th century leather bindings...she is especially known for her tasteful and intricate pointillé work, with which she began to experiment from a very early stage."); Bryan Maggs, "#89," The Wormsley Library (2007), p. 214 (cited above)

Item #887