Pair of model incunable schoolbooks | English author, scarce provincial press

Pair of model incunable schoolbooks | English author, scarce provincial press

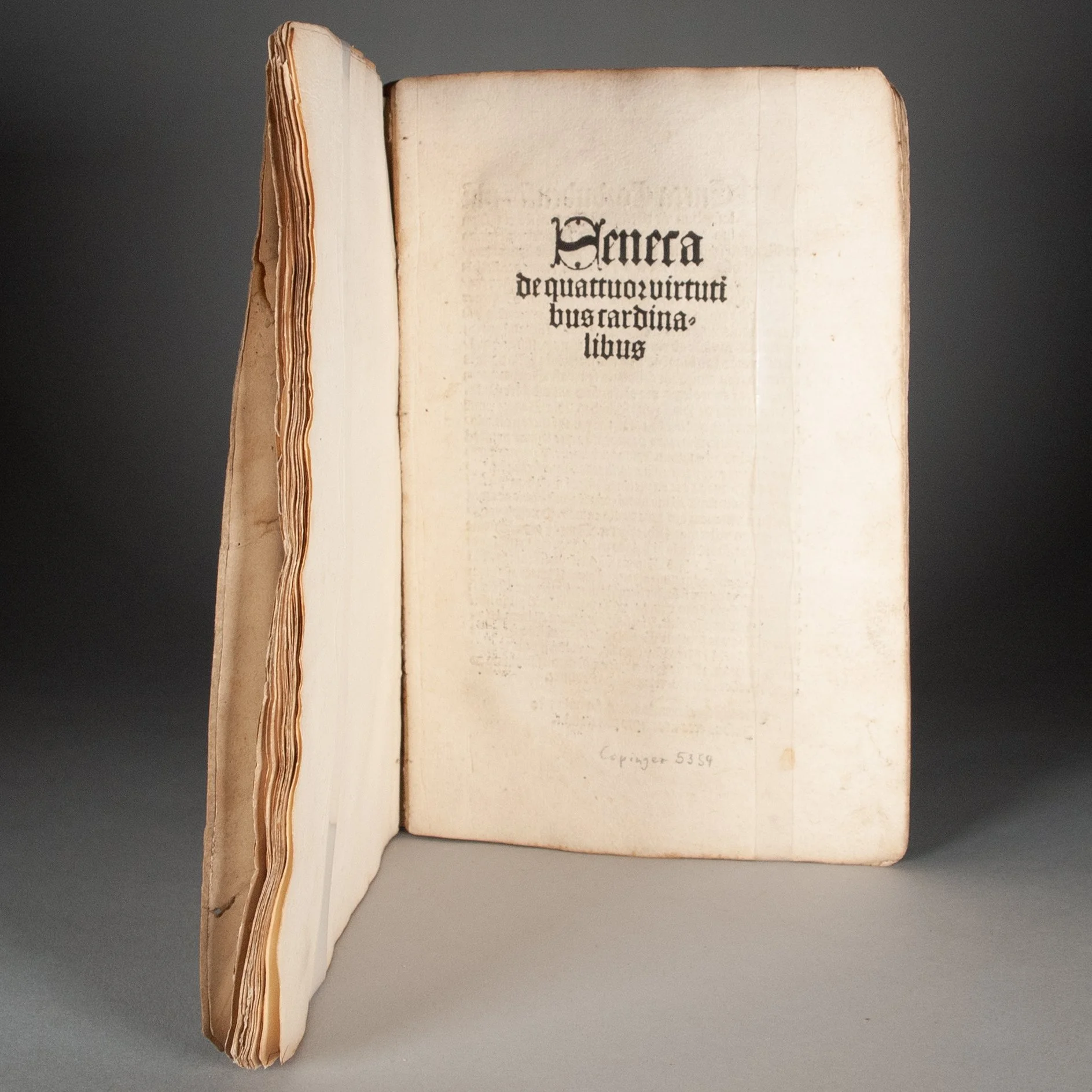

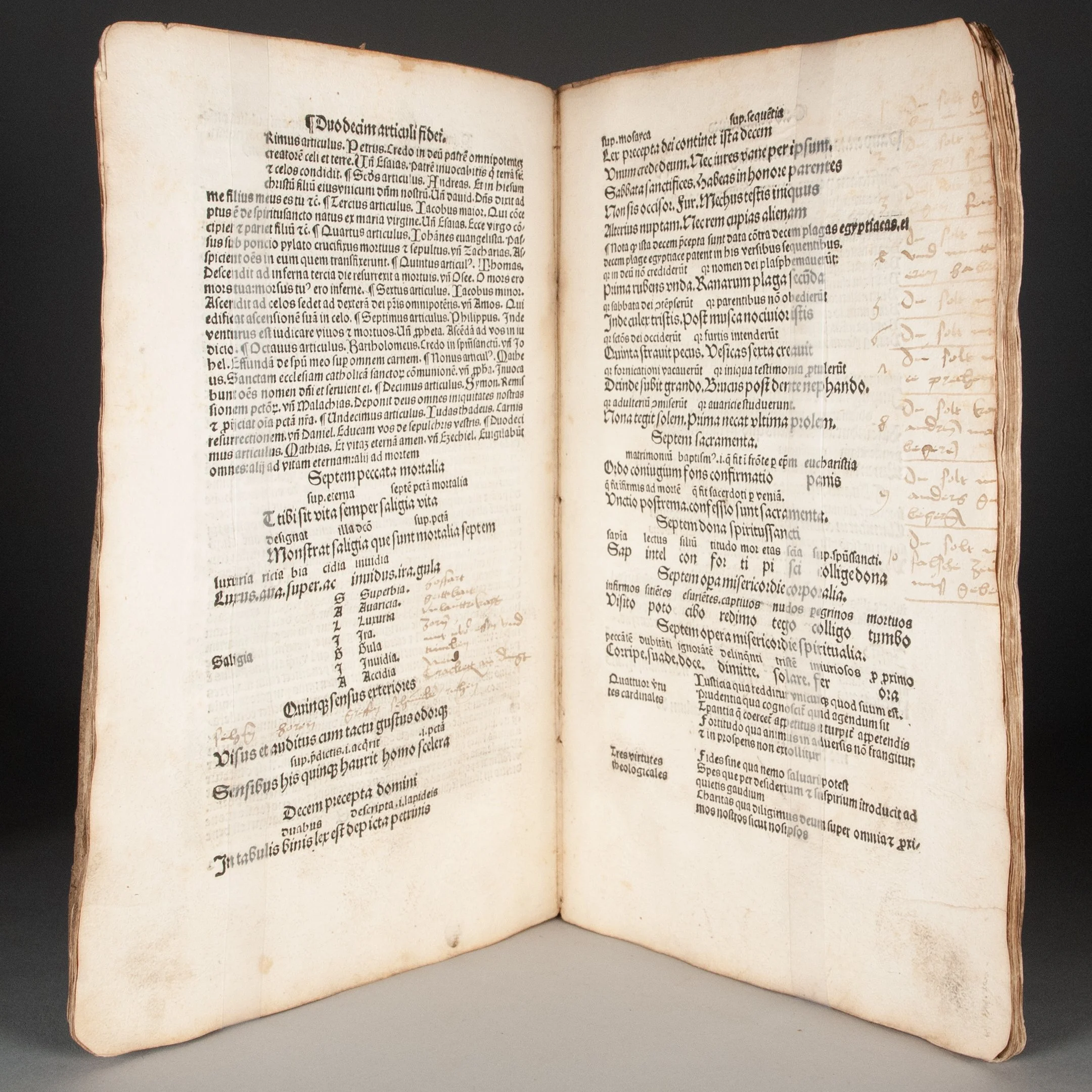

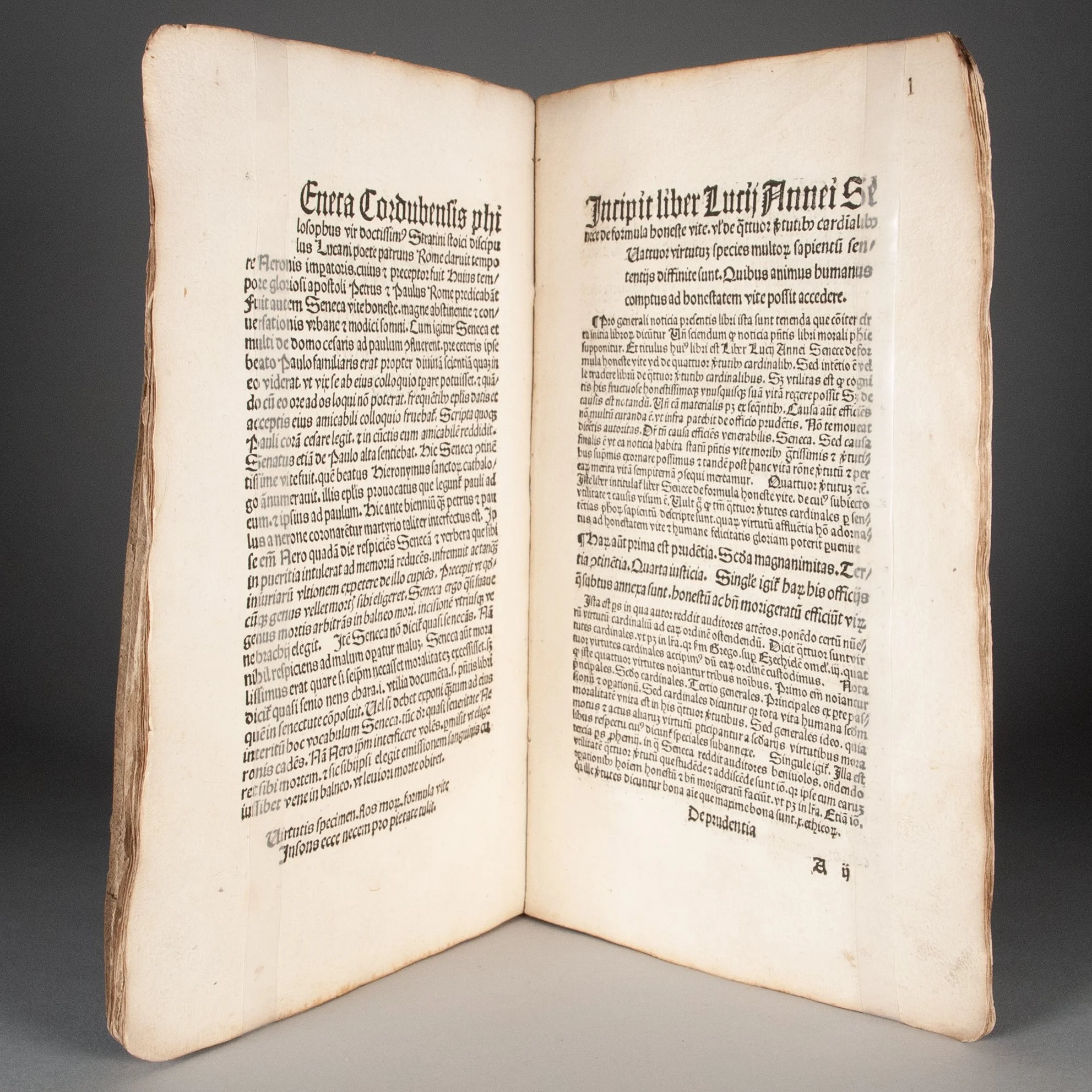

Peniteas cito | Poeniteas cito | Poenitentionarius de confessione [bound with] De quattuor virtutibus cardinalibus

Peniteas cito by William de Montibus | De virtutibus by Saint Martin of Braga (Martinus Dumiensis | pseudo-Seneca)

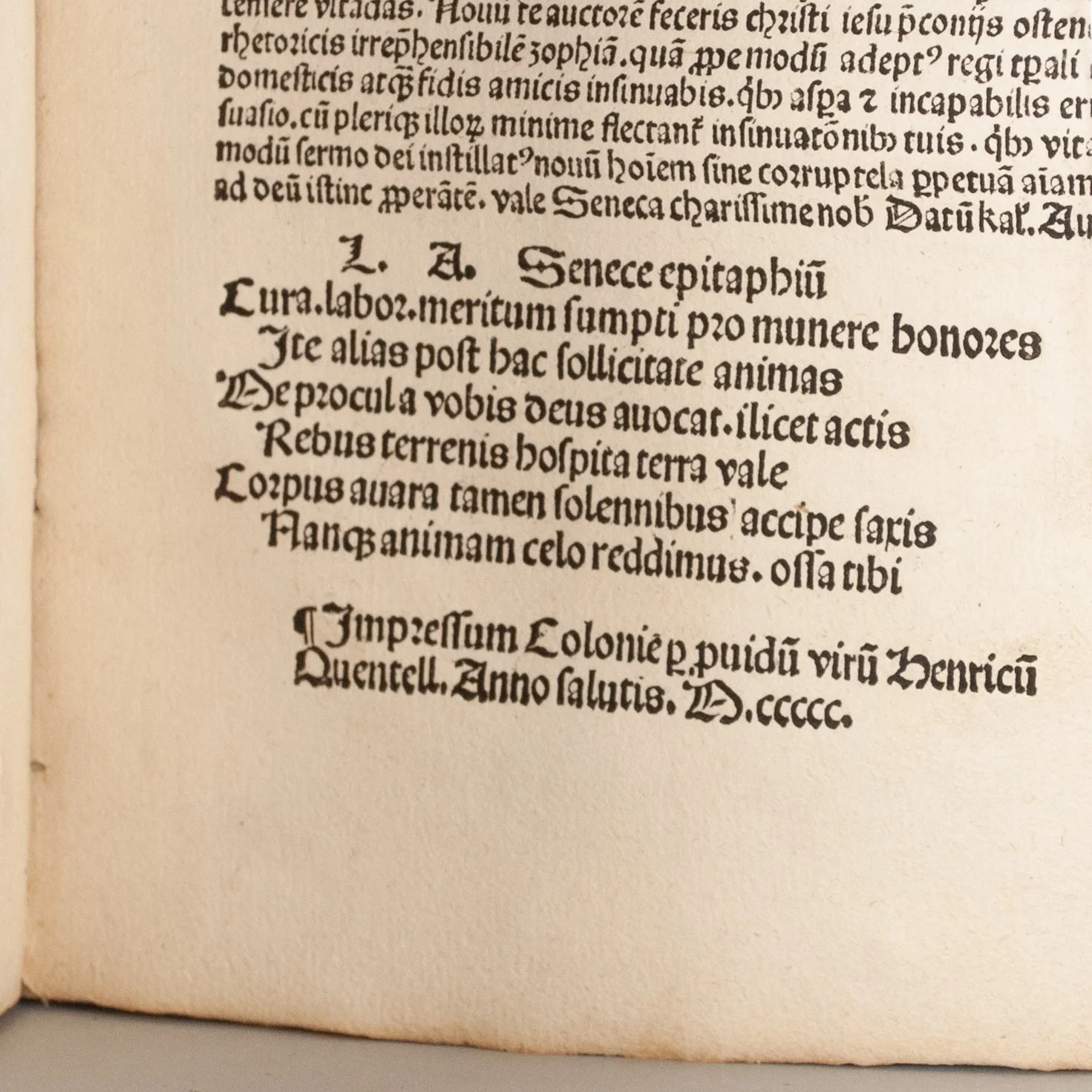

Metz: Caspar Hochfeder, ca. 1500 | Cologne: Heinrich Quentell (Quentel), 1500

[14] of [16]; [16] of [16] leaves | 4to | a^6(-a1 title) b^6 c^4(-c4 blank); A-B^6 C^4 | 205 x 136 mm

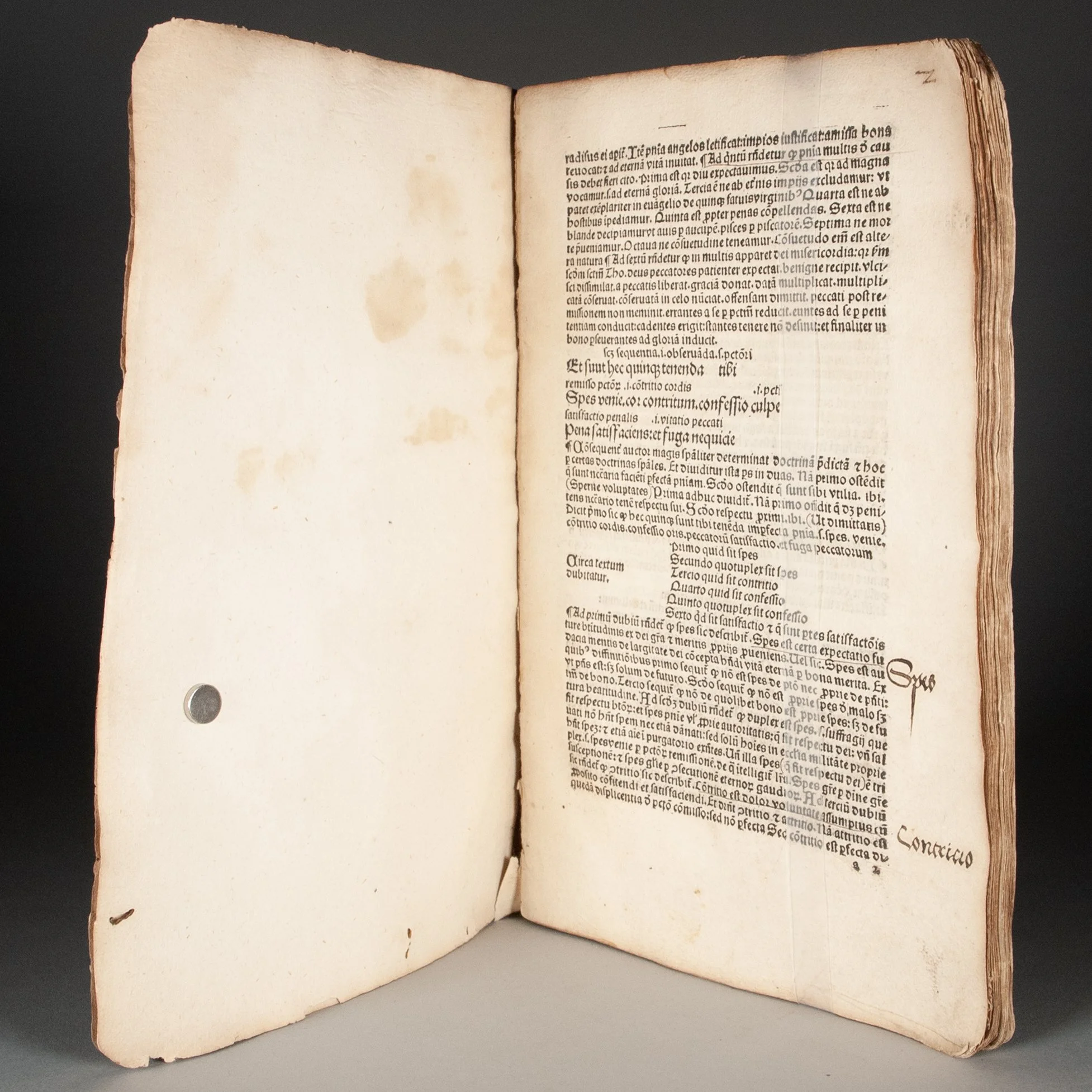

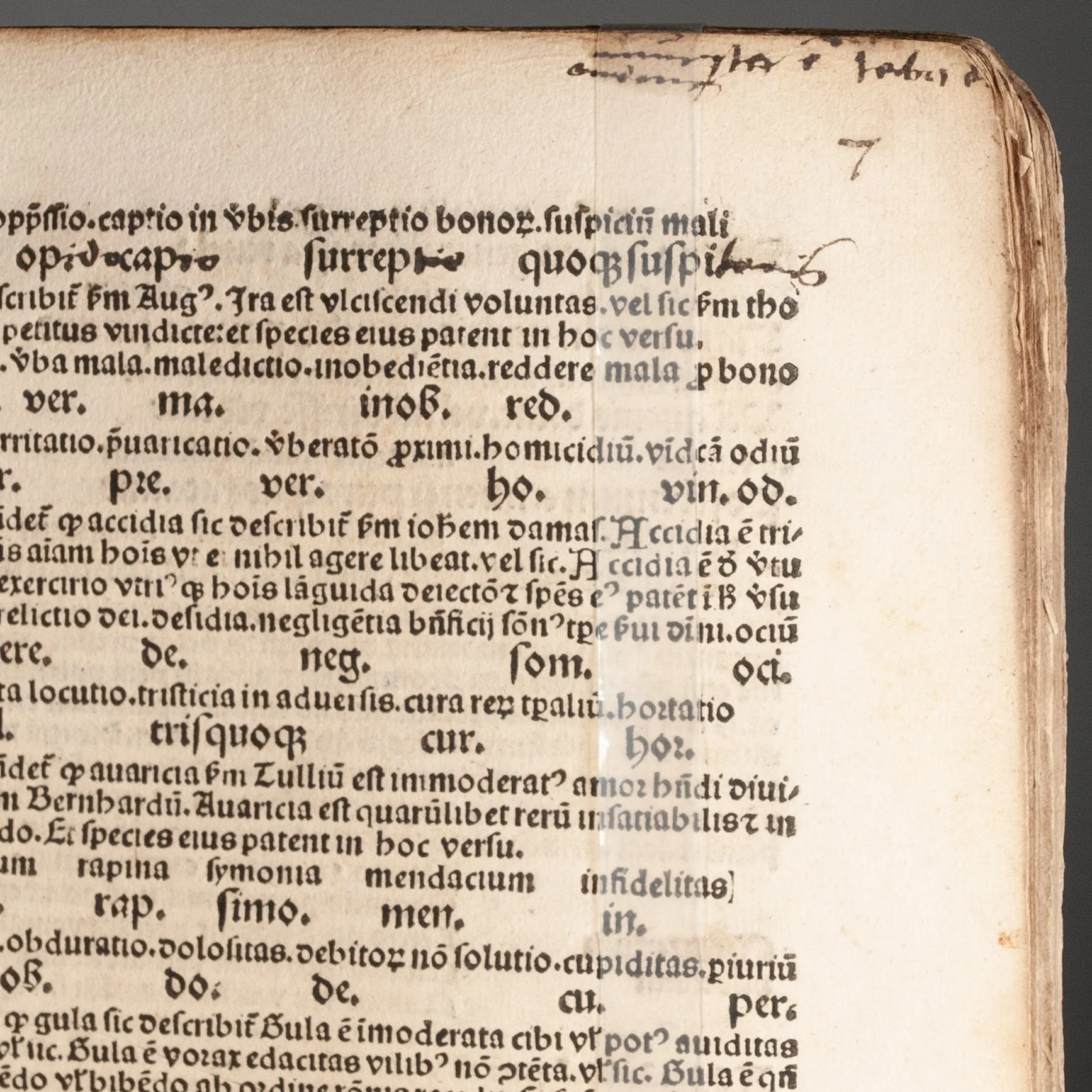

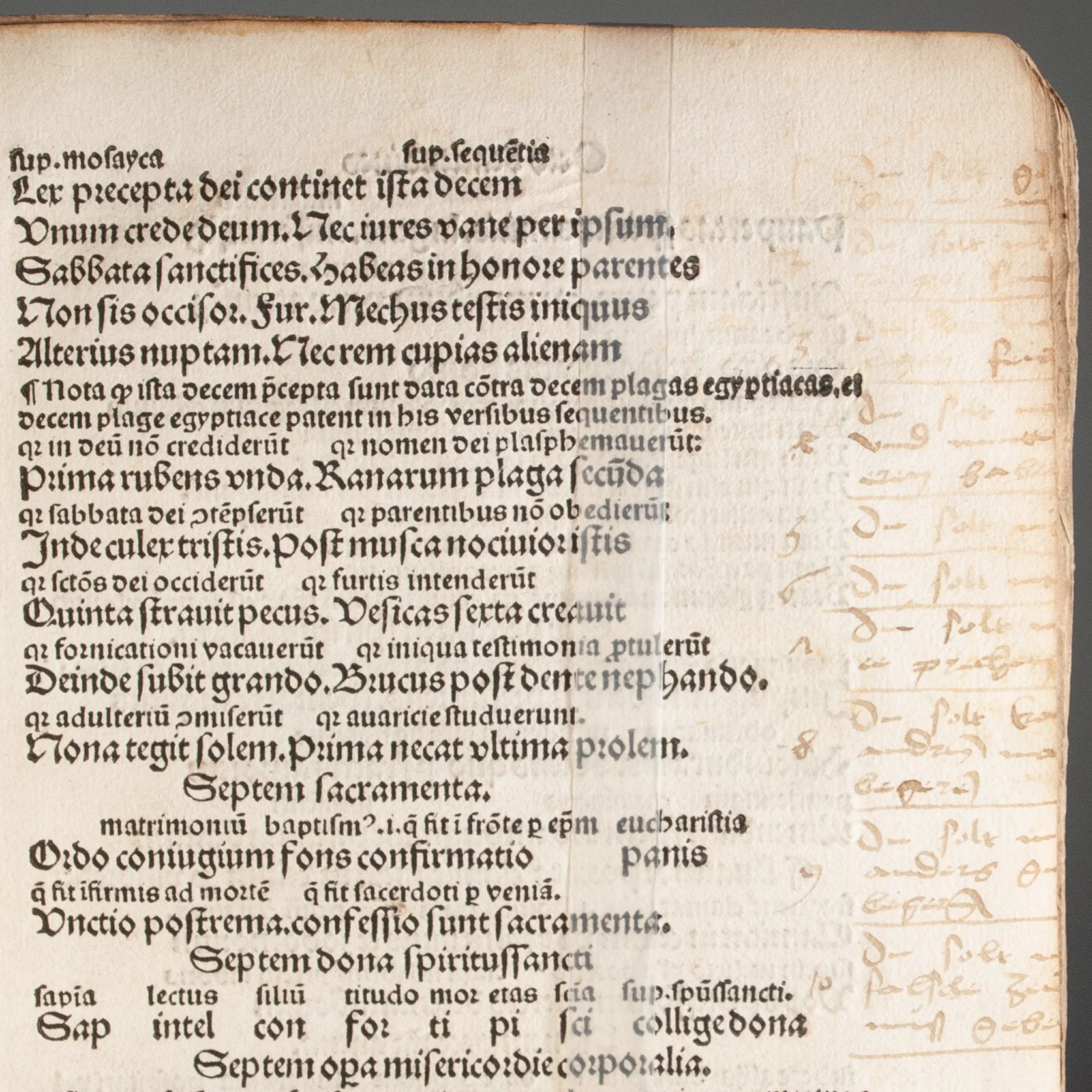

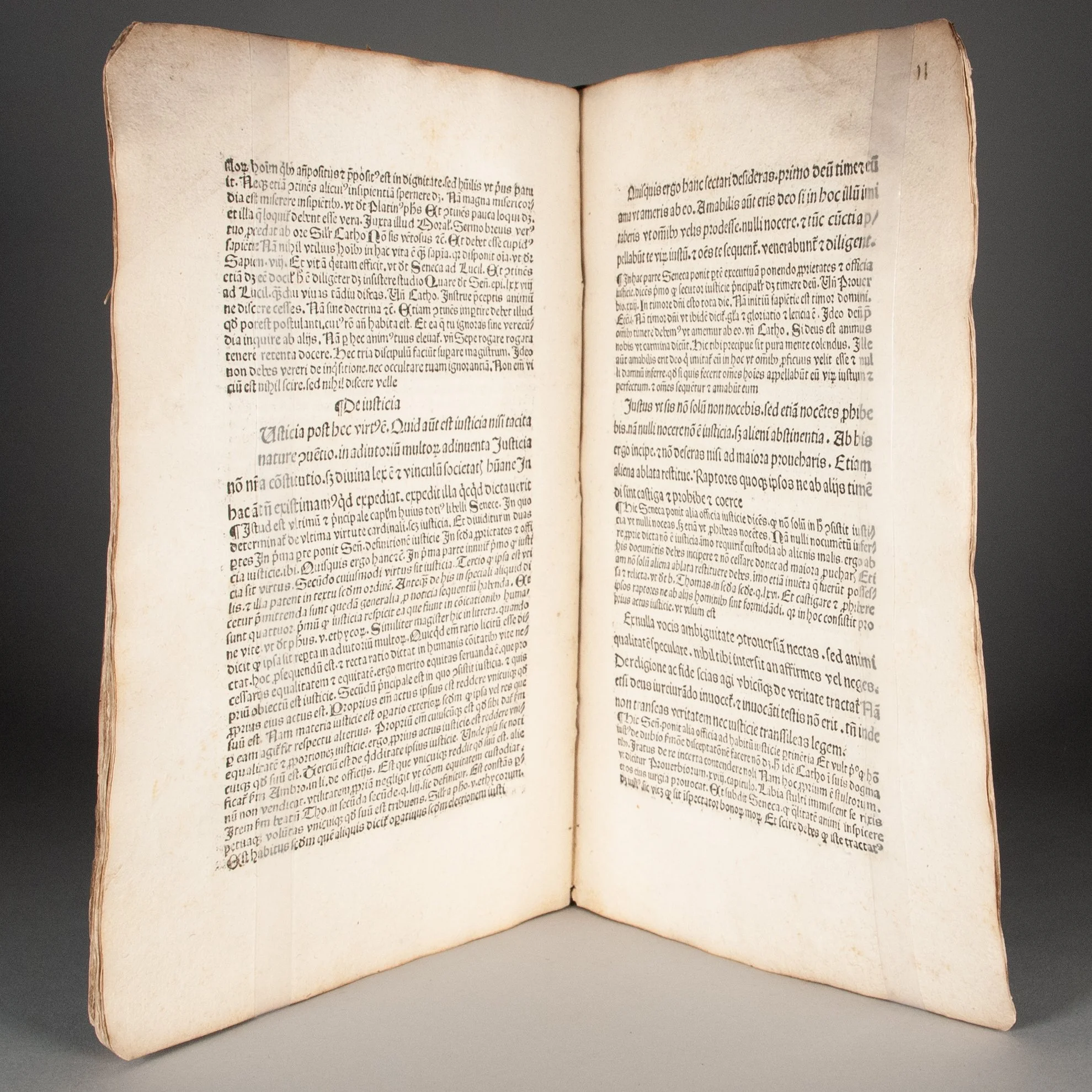

A later edition of the tremendously popular Peniteas cito, a pastoral text that taught the basics of conducting confession in brief, memorable verse—"the first confessional treatise written in verse," in fact, "which made it especially suitable for classroom application" (Woods and Copeland). The work is frequently attributed to John of Garland, and sometimes Petrus Blesensis, though more recent scholarship seems to favor the English teacher William de Montibus. ¶ Here bound with a later edition of the 6th-century Portuguese missionary's moral treatise, "not only the first, but also the most widely diffused medieval treatise confined to the cardinal virtues" (Bejczy). The work was long attributed to Seneca, but is now recognized as a repackaging of one of his lost works. The misattribution is understandable, as the work is surprisingly light on the kind of Christian moralizing we might expect from an early theologian. "Indeed, Martin sets forth an entirely Stoic treatment of the virtues as moral guidelines of the public life. God is only mentioned as an abstract entity, not as a Redeemer, while references to the Bible and to the life in the hereafter are absent" (Bejczy). ¶ "This was one of the most widely read works of the Middle Ages" and survives in more than 700 manuscripts (Costa). First printed ca. 1470, the work proved quite popular into the age of the print, too, with some three dozen appearances preceding ours—sometimes on its own, sometimes appended to larger collections, and occasionally in translation. Some thirty further editions followed through the middle of the 16th century. The work stands out for being one of very few early medieval treatises devoted to the subject of virtues and vices (and should not be confused with one of the same name by 14th-century Henricus Ariminensis). ¶ Both texts are model examples of editions produced for the student market. The Peniteas text proper has a printed interlinear gloss to help readers parse the Latin; the St. Martin text proper is leaded, with a full millimeter between lines, the added interlinear white space providing students with a platform for their own notetaking; both texts are accompanied by robust commentaries, which both students and their instructors could tap for guidance; and the slight format, small quartos of just 16 leaves, would have been relatively inexpensive to purchase and could have been bound up with any number of similarly sized texts. ¶ To be sure, the Peniteas cito "would come to form a key part of the grammar school curriculum over the 13th century, which indicates that not only the officials of the episcopate, but also local grammar masters were thinking of the needs of the schools to train clergy for the cure of souls"—hence our printed gloss to assist readers with the Latin (Reeves). Dozens of 15th-century editions survive, dating as early as the mid-1480s, and many manuscripts. "More important than the physical remains," however, "is the evidence that this poem was one of the mainstays of primary education. [It was] an introductory text, memorized by students during their formative years in grammar and theological schools" (Goering via Woods and Copeland). ¶ For its part, "Cologne was the seat of a flourishing university which was drawing an increasing number of students from the prosperous artisan families of the Rhineland. The City of the Three Kings, as it proudly called itself, with its shifting student population, offered a market unequalled in northern Europe, perhaps anywhere, for cheap copies in capsule form of every sort of standard reading matter" (Winship). And if Cologne was one of Europe's great centers of schoolbook production, Heinrich Quentell was among its leading producers, who "alone printed scores of text-books for the use of students and instructors" (Haraszti). Printed in far greater numbers than could have been locally consumed, many schoolbooks were exported for use elsewhere in Europe. ¶ ISTC reports three copies of the Peniteas in North America (Univ of Virginia, Huntington, Stanford), and a single copy of the St. Martin (Library of Congress). Among auction records, we find no other sales for this Quentell edition of the St. Martin, and we find just ten other sale records for anything from the provincial French press of Metz. To be sure, ISTC records just 18 Metz incunables altogether, where Hochfeder was one of just two printers active in the 15th century.

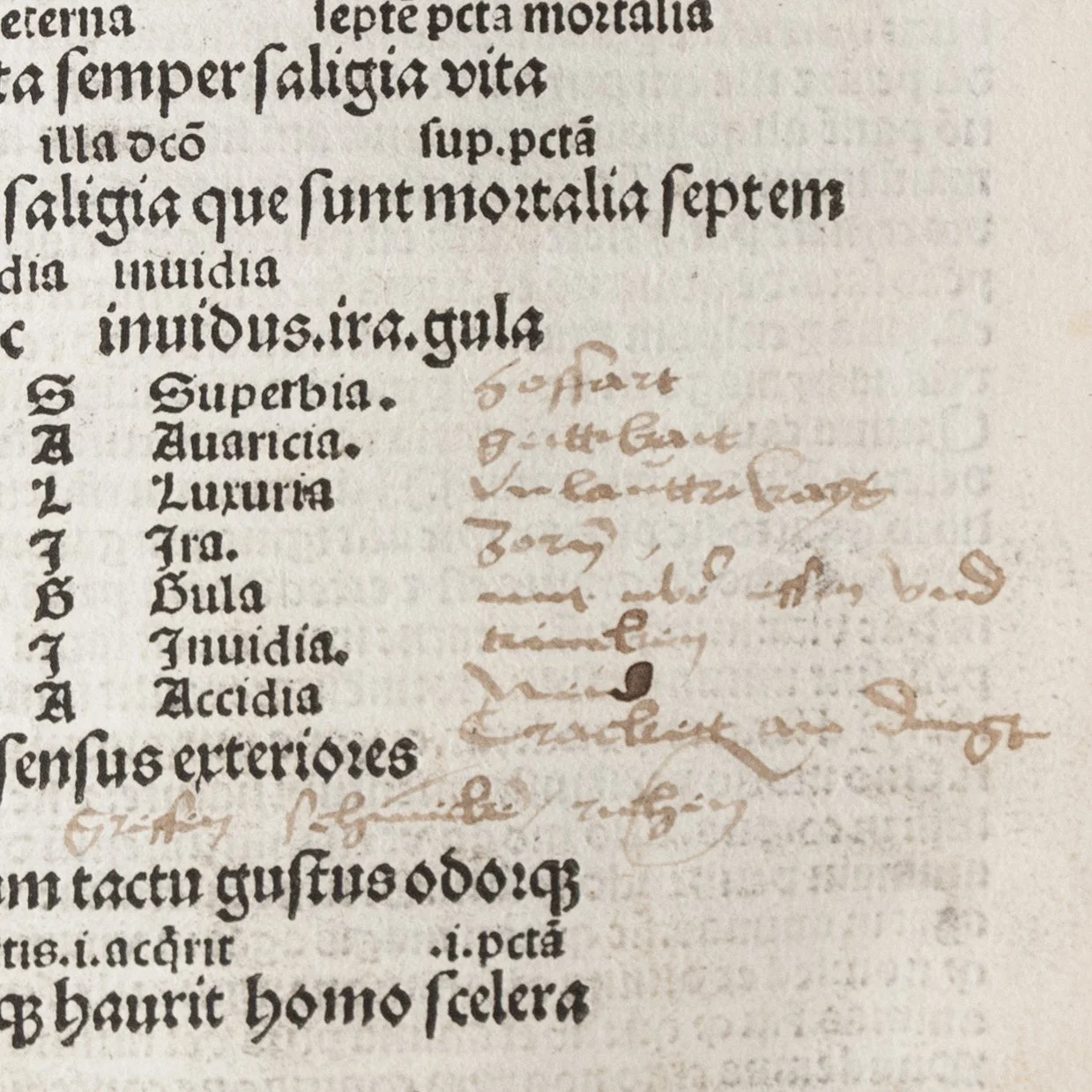

PROVENANCE: The Peniteas with some scattered early annotations: a few keywords from the printed text copied in the margins, presumably to facilitate navigation; on leaf b1r, a few abbreviations in the interlinear gloss have been expanded, suggesting a reader who was indeed working on their Latin; and most compelling, on c2v-c3r, annotations in German, providing clear evidence of an early reader using their vernacular to make sense of the Latin. They've penned beside the Seven Deadly Sins their translations into German: Zorn for the printed Ira, for example, and Hoffart for Superbia. And in the margin beside the Ten Commandments in Latin, our early reader has translated them into German (Du solt..., numbered 1 through 10). ¶ Old, aborted attempt at a handwritten index on the final blank page of St. Martin.

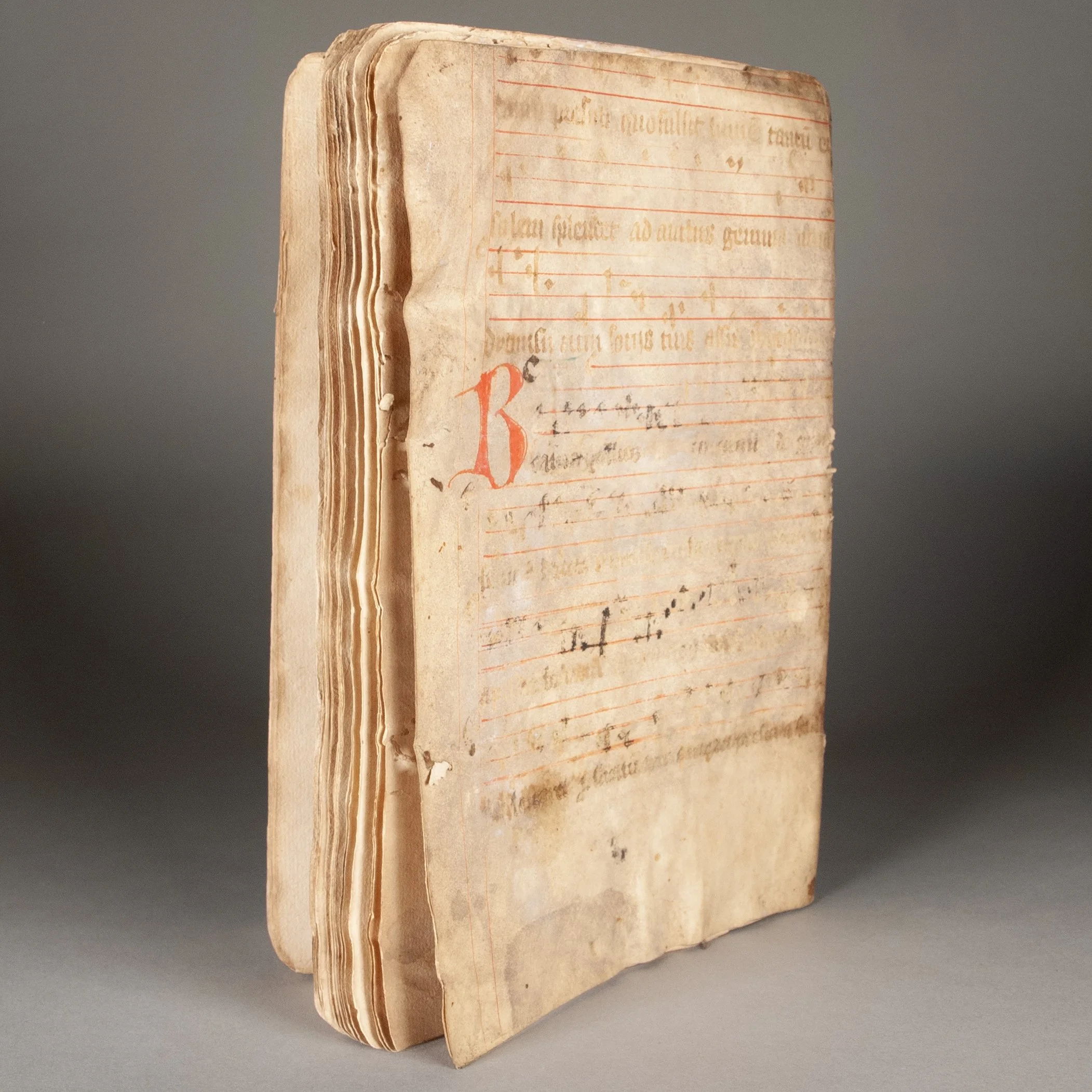

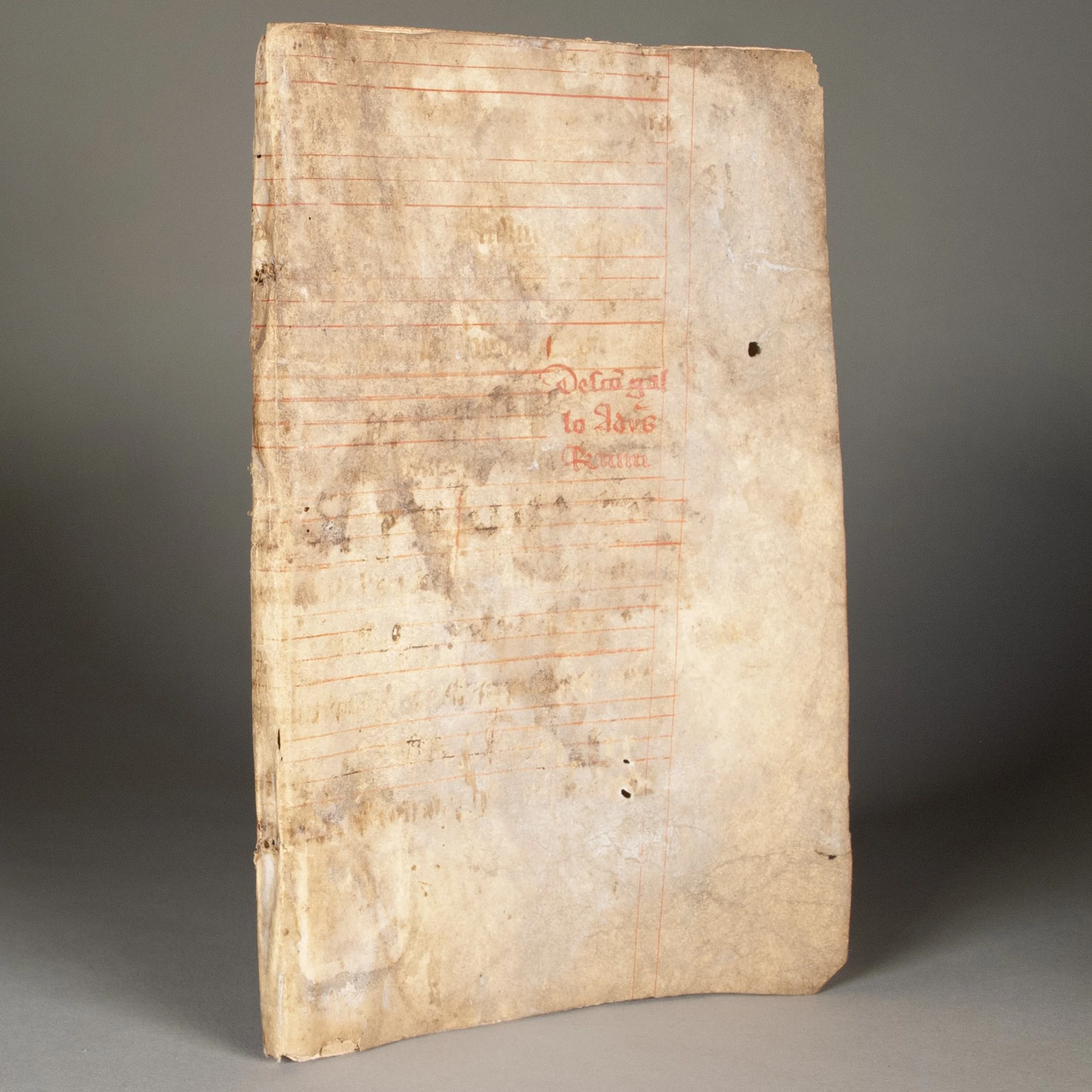

CONDITION: In a simple early binding of late medieval manuscript waste, entirely notated music and probably from a liturgical text. The binding's fly-leaves bear a watermark of crossed keys within a shield, surmounted by the letter R, strikingly similar to Heawood 2822 (ca. 1550). Briquet, too, generally places similar crossed keys watermarks (albeit without the R) in the sixteenth century. ¶ Peniteas lacking the title leaf and final blank leaf, but the St. Martin is complete. The sewing mostly lost, so the parchment wrapper now functions mostly as a portfolio for loose gatherings; closed tear in the margin of St. Martin's leaf A6, not affecting text; a few small wormholes, not affecting text; scattered light soiling, and the edges of the leaves a bit dusty and crinkled; mild dampstain at the inner margin of Peniteas, touching a little text. Parchment binding heavily worn, the front cover soiled, and with scattered worming.

REFERENCES: ISTC ip00848000 (Peniteas), is00421000 (St. Martin); Catalogue of Books Printing in the XVth Century Now in the British Museum, v. 3, p. 664, IA. 12725 (Peniteas) ¶ On the Peniteas: Andrew Reeves, "Teaching Confession in Thirteenth-Century England: Priests and Laity," A Companion to Priesthood and Holy Orders in the Middle Ages (2016), p. 258 (cited above); Marjorie Curry Woods and Rita Copeland, "Classroom and Confession," The Cambridge History of Medieval English Literature (2002), p. 385 (cited above; "The popularity of this text all over Europe during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was extraordinary"); Malcolm Walsby, Booksellers and Printers in Provincial France 1470-1600 (2020), p. 459 (brief bio of Hochfeder) ¶ On Martin's work: István P. Bejczy, The Cardinal Virtues in the Middle Ages (2011), p. 55-57 (cited above; "The treatise is entirely devoted to the cardinal virtues, which Martin strikingly avoids to present as ingredients of Christian morality...Most modern commentators assume that the Formula goes back to a lost work of Seneca. From the tenth century, the work was usually attributed to Seneca himself...a circumstance which may have fostered the extraordinary popularity of the work in the Later Middle Ages. It survives in over seven hundred manuscripts and reached at least forty printed editions in the fifteenth century."); C.D.N. Costa, Seneca (2014), unpaginated ebook (cited above); István P. Bejczy and Michiel Verweij, "An Early Medieval Treatise on the Virtues and Vices Rediscovered," The Journal of Medieval Latin 16 (2006), p. 208 ("Treatises on the virtues and vices constitute a medieval genre of great popularity," but "early medieval specimens on the genre are relatively rare," the authors citing the present, Alcuin's De vitiis et virtutibus, and a newly discovered 9c or 10c work); Helena Avelar de Carvalho, An Astrologer at Work in Late Medieval France (2021), p. 371n14 ("also called Formula honestae vitae, a moral compendium by Martin of Braga, adapted from Seneca's work") ¶ On schoolbooks: Severin Corsten, "Universities and early printing," Bibliography and the Study of 15th-Century Civilisation (1987), p. 94 (“When one considers that the Bachelors who taught in the afternoons were themselves still students, and also were not yet quite of an age to command respect, one gets a realistic idea of the quality of these teaching arrangements. It was certainly in the interests of the students that these junior teachers should not draw on their own resources, but should confine themselves to reciting the commentaries of the masters.”), 95 (“In the mid-1480s, the printing of editions with commentary began, and these soon clearly exceeded in number the editions which provided the text on its own. The commentaries of professors, printed at the places where they taught, were intended not only for use at the professors’ own universities, but were disseminated far and wide.”); George Parker Winship, Printing in the Fifteenth Century (1940), p. 56 (cited above); Zoltán Haraszti, "Dr. Sarton on Scientific Incunabula," Isis 32.1 (July 1940), p. 55 (cited above); Lotte Hellinga, Incunabula in Transit (2018), p. 213 ("Cologne produced textbooks used in many universities"); Ann M. Blair, Too Much to Know (2010), p. 71 ("Not all the annotations found in early modern books were reading notes: in school editions (identifiable by the double-spacing that allowed for interlinear notes) pupils typically wrote down commentary dictated to them in class"); Philip Gaskell, New Introduction to Bibliography (2012), p. 14 ("provided that the gap between them is 0.5 mm. or less (up to 1 mm. in the case of very large type) the lines are probably set solid, but if it is wider they are either leaded or printed from a fount cast on an oversize body") ¶ On the watermarks: Edward Heawood, Watermarks, Mainly of the 17th and 18th Centuries (1950), #2822; C.M. Briquet, Les Filigranes, v. 2, #3904-3910

Item #916