The dark horse of Parisian hours | Only copy on paper

The dark horse of Parisian hours | Only copy on paper

Hore s[e]c[un]d[u]m Vi[rginis] i[n] Romanu[m] lo[n]gu[m] [Horae secundum usum Romanum | Hours for the use of Rome]

Paris: Thomas Kees (Wesaliensis), [1511]

[216] p. | 8vo | [A]^8 B-N^8 O^4 | 178 x 107 mm

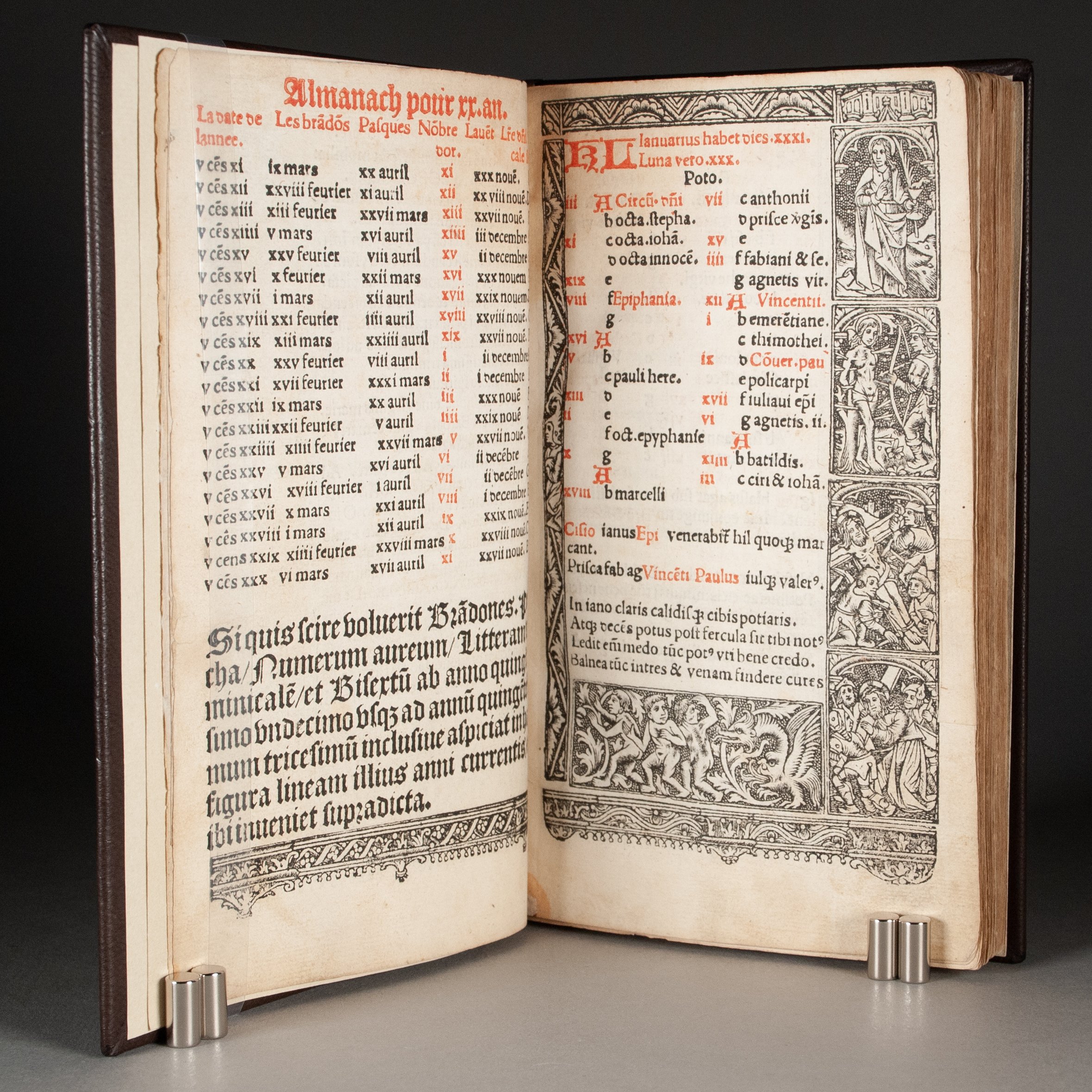

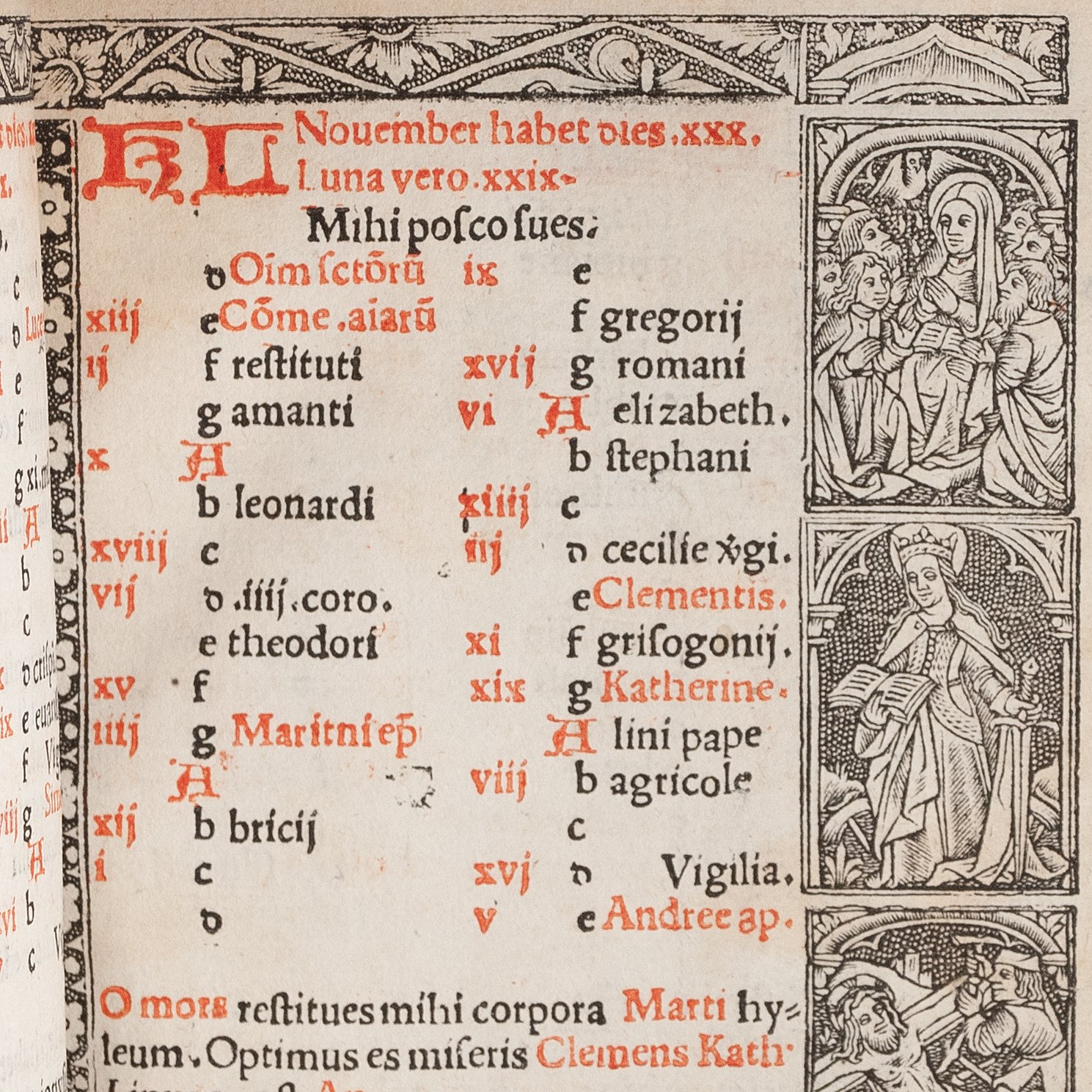

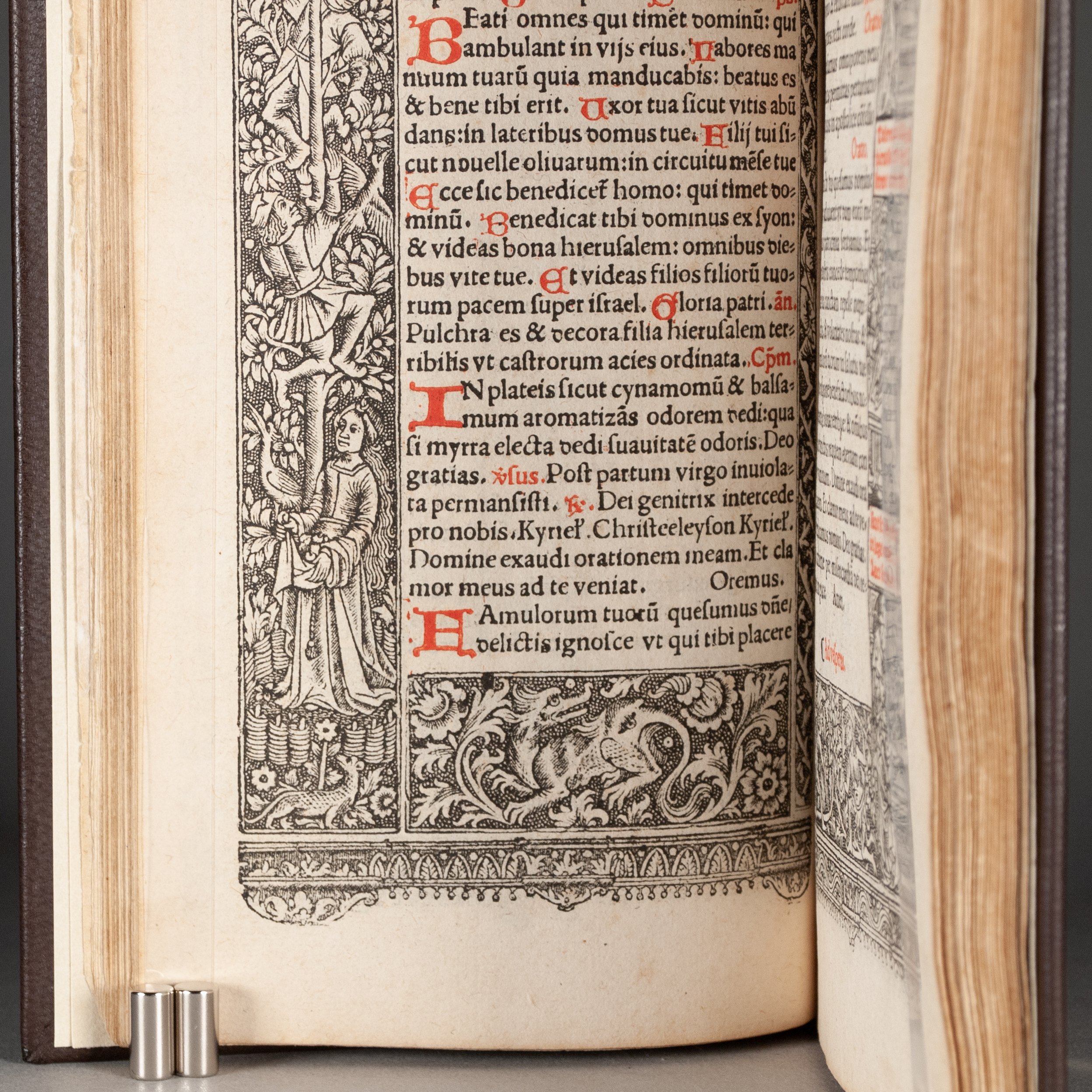

One of just three known copies of this Latin hours for Roman use, and the only one on paper. As the printer’s only book of hours, it’s for the collection that has them all. And as a quintessential example of this epoch-making Parisian genre, with much of its illustration based on the iconic designs from Philippe Pigouchet’s editions, it’s equally for the collection that has none. Eclipsed by the likes of Vérard, Vostre, Pigouchet, and Kerver, Kees was on the ragged fringe of this massively lucrative market. His output was varied, encompassing material liturgical, humanist, legal, and mathematical. He commonly partnered or printed for others, these outnumbering his own imprints by at least four to one. He died poor, his widow unable to cover his debts. His name is invariably missing from the celebrated catalogs of early French printing. Where his peers would deploy a custom device on their titles, here Kees uses a more generic illustration copied from Pigouchet. His hours isn’t in Ruth Mortimer’s French Sixteenth Century Books, nor in Hugh Davies’s catalog of the Fairfax Murray collection. He’s not among the 23 producers of Parisian hours in Robert Brun’s Livre français illustré de la Renaissance, nor even among the 42 Brunet covers in the Notice sur les heures gothiques appended to his Manuel du libraire. Even Elsbet Colmi didn't turn up a copy of his Hours for her dedicated bibliography of Kees's work. Which makes the present production so compelling. Kees was the dark horse of Parisian hours, a printer who’d worked repeatedly for others, and finally, after a decade, set out to match the city’s best work under his own name. ¶ All the standard texts and iconography are here: an anatomical man on the title verso, a vernacular French cut after the version used by Pigouchet; an almanac; a calendar for 1511-1530, flanked by small cuts of the Passion, various saints, the Four Evangelists, seasonal activities, and grotesques, quite a few repeated; the sequentiae of the gospels, opening with a nearly full-page illustration of St. John and the poisoned cup; the Passion, with an illustration of Judas’s betrayal of Jesus; the Hours of the Virgin Mary, opening with two large illustrations; the Penitential Psalms and Litany, opening with a large cut of David and Uriah; the Office of the Dead; Hours of the Cross, with a nearly full-page Crucifixion; Hours of the Holy Spirit, with the usual Pentecost woodcut; and suffrages to various saints, typically paired with a criblé cut. Also included are some preparations for Mass, as well prayers for afterward, which must have lent a liturgical hand to its owner; an Office of the Immaculate Conception, repeating the Annunciation woodcut; an Office of St. Barbara; the Seven Prayers of St. Gregory; and several pages of additional prayers, including a plague prayer to St. Roche. We were surprised to see in a prayer on N6v—perhaps intentional, perhaps not—that a few instructions for recitation (always printed in red) slipped into the vernacular, the only deviation from Latin we find in Kees’s letterpress text. ¶ In addition to the large title cut and the anatomical man on its verso, Kees presents 16 large illustrations (one repeated), very nearly full-page, plus scores of smaller cuts and border pieces (some also repeated). Much of this has been copied from designs in Pigouchet’s hours. The resemblance of our David and Uriah to one of his is uncanny. Our Tree of Jesse, too, is traceable to Pigouchet’s design, and we suspect the same for most, if not all, of our large illustrations. Many of our border pieces, as well, are copies (frequently reversed) of metalcuts that appeared in Pigouchet’s hours, at least by 1498—our Dance of Death series, for example, which flanks the Office of the Dead, as well as the full-length border pieces featuring humble figures among trees and vines on criblé backgrounds (compare ours to ISTC ih00395000, Pigouchet/Vostre, 1498, in which Ruth Mortimer considered borders “at their best” among Harvard’s collection). ¶ For those less familiar with the genre, the printed book of hours, like the manuscripts upon which they were based, was easily among the most popular lay books of its day. While not strictly a liturgical book, its contents were born from the medieval psalter, which evolved to include the Hours of the Virgin, the Office of the Dead, and other prayers. “Now the Psalter is dropped, and what were once additions now form the core of the book, becoming the essence of a collection of texts which is open to expansion” (Coppens). That core set of texts was frequently paired with standard illustrations. But the expansions, the smaller texts that might be added—like our Office of St. Barbara, or the plague prayer to St. Roche—combined with the endlessly captivating borders to produce a wondrous variety. “With little scope for varying the subjects of the illustrations, both fifteenth- and sixteenth-century printers and publishers turned to the borders as a means of distinguishing their work,” which “reached their height in the Pigouchet-Vostre editions with a full set of subjects and secondary texts related closely to the major text divisions” (Mortimer). While books of hours were certainly printed elsewhere, no city could compete with the Paris printers. ¶ We find only the BnF copy and another on vellum with a Dutch bookseller at time of cataloging.

PROVENANCE: Ownership inscription at foot of H4v and L4v: Fr[atr]is Gregi. Martinelli. Books of hours were commonly wedding gifts for the well heeled, and we frequently read how women owned them at greater rates than just about any other book. The ubiquitous vernacular heures surely underscore these claims. This Latin book of hours, owned by a monk, should add some nuance to the common tales of ownership and use. We suspect its apparent Italian ownership is no coincidence either. Kees notes in his colophon that he’s near the Italian College, and no doubt Paris’s reputation for theological training drew many aspiring clergy over the Alps. Offering a Latin hours for Roman use must have made good sense. Kees was no stranger to serving an international market. In 1510, he produced for a London merchant a Seville breviary, “one of the few foreign editions” for the Spanish liturgical market in the post-incunable period (Norton). ¶ Opening line of Vulgate Psalm 42 on an old front fly-leaf (Judica me Deus…).

CONDITION: New dark brown goatskin by James Reid-Cunningham, simply tooled in blind and retaining two old fly-leaves. Printed in red and black throughout, and the only copy not decorated by hand. Leaf O1 mis-signed O2 (plague prayer to St. Roch continues seamlessly between N8v and the following leaf). Foliation penciled in upper right repeats fol. 33. ¶ First leaf with loss at the fore-edge affecting the borders, but filled; long closed tear across upper corner of title, discreetly repaired; a few small marginal tears in the first few leaves, sparing the borders; scattered moderate soiling, the title somewhat heavier, and some very faint scattered dampstaining in the lower margin of the first couple gatherings.

REFERENCES: USTC 183113; Hanns Bohatta, Bibliographie der livres d’heures (1909), p. 32, #847 (has correct foliation, but overlooks the final gathering, citing Rosenthal); Jacques Rosenthal, Occult sciences, history of superstition, Former series, Catalogue 83 (1895?), p. 102, #1459 (possibly our copy, en partie taché et fortement piqué, though any dampstaining that remains is extremely faint) ¶ On the printer: A. Boinet, “Courrier de France,” La bibliofilía 51.2 (1949), p. 211 (on the BnF’s recent acquisition, a vellum copy (sur vélin): “a book of hours of the greatest rarity, of which we know no other copy”); Ph. Renouard, Documents sur les imprimeurs, libraires (1901), p. 141 (“the said Thomas died a poor man and his wife doesn’t have the means to pay” his rent debt); J. Mathorez, Les étrangers en France sous l’ancien régime (1921), v. 2, p. 50 (“among the first German printers established in Paris was Thomas Kees, of Wesel; his presses were situated on rue des Carmes”); F.J. Norton, Printing in Spain 1501-1520 (Cambridge Univ, 1966), p. 136 (cited above); Elsbet Colmi, "Thomas Kees Wesaliensis: Aus der Werkstatt eines Weseler Druckers in Paris 1507-1515/16," Festschrift für Josef Benzing (1964), p. 68 ("The first printer from Wesel"), 69 ("We know neither the workshop nor the master from whom he learned the printing trade...An overview of the projects from his office shows us the everyday life of a small printer in the service of various booksellers, publishers, and clients") ¶ On Pigouchet’s cuts: Hugh Davies, Catalogue of a Collection of Early French Books in the Library of C. Fairfax Murray (London, 1961), p. 277 (Pigouchet’s David and Uriah), 281 (Pigouchet’s version of our title cut), 282 (Pigouchet’s Tree of Jesse); Ruth Mortimer, Harvard…Catalogue of Books and Manuscripts: Part I: French 16th Century Books (1964), p. 365-366; Le livre & la mort XIVe-XVIIIe siècle (Cendres, 2019), p. 265 (reproducing some of Pigouchet’s Dance of Death borders); Norma Levarie, The Art & History of Books (Heineman, 1968), p. 145 (“Pigouchet, with his publisher Simon Vostre, produced both the most numerous and the most typical of the fifteenth-century Horae”) ¶ General context: David Bland, The Illustration of Books (Pantheon, 1952), p. 42 (printed hours “were the direct descendants of the manuscript Books of Hours…and contained ten or twenty illustrations which played a definite part in their religious teaching. It is in this that one of their chief interests lies for us because they mark a departure in the use of illustrations. Here it is neither decorative, nor illustrative nor explanatory…but it combines all three functions and adds to them the symbolism we have already seen in the earlier books.”); Frédéric Barbier (Jean Birrell, tr.), Gutenberg’s Europe (Polity, 2017), p. 233 (“The principal speciality of the Parisian book trade in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries was its famous beautifully illustrated and small format Books of Hours”); Mary Beth Winn, “Illustrations in Parisian Books of Hours: Borders and Repertoires,” Incunabula and Their Readers (British Library, 2003), p. 31 (hours have “rather complex combinations of texts, both Latin and vernacular, and images, both sacred and secular, in layouts that vary incessantly even when certain patterns have become conventional. Perhaps more than other volumes, moreover, Books of Hours require attention to copy-specific details.”), 51 (on borders: “early printers obviously considered them worthy of attention, in part because they offered the greatest opportunities for invention and innovation…Significant, too, is the fact that printers sought to correlate border designs with the core texts,” e.g. Dance of Death for Office of the Dead. “Although respect for this correlation must have waned as border pieces wore out, the principle of relating border to central text remained constant and seems to have governed the vast majority of editions. The borders reinforced not only the teaching of the main illustrations, as Pollard noted, but also that of the texts themselves.”); Roger Chartier (Lydia G. Cochrane, tr.), The Cultural Uses of Print in Early Modern France (Princeton, 1987), p. 149 (“The books that sixteenth-century merchants and artisans in Amiens owned were for the most part religious books, and particularly Books of Hours…Books of Hours were often the only sort of book owned”), 150 (“the Book of Hours provided a basic market for the publishing profession in the sixteenth century, since it satisfied a clientele of ‘notables’ as well as a ‘popular’ clientele for whom it was the most usual, and often the only, purchase”); Christian Coppens, Leuven in Books, Books in Leuven (1999), catalog entry #53, p. 163 (“Though books of hours for laymen are not liturgical books, the order of their contents and the sequence of their texts were inspired by the breviary, and they became the prayer-book par excellence of the devout layperson”), #55, p. 170 (cited above)

Item #672