Annotated bespoke legal compendium

Annotated bespoke legal compendium

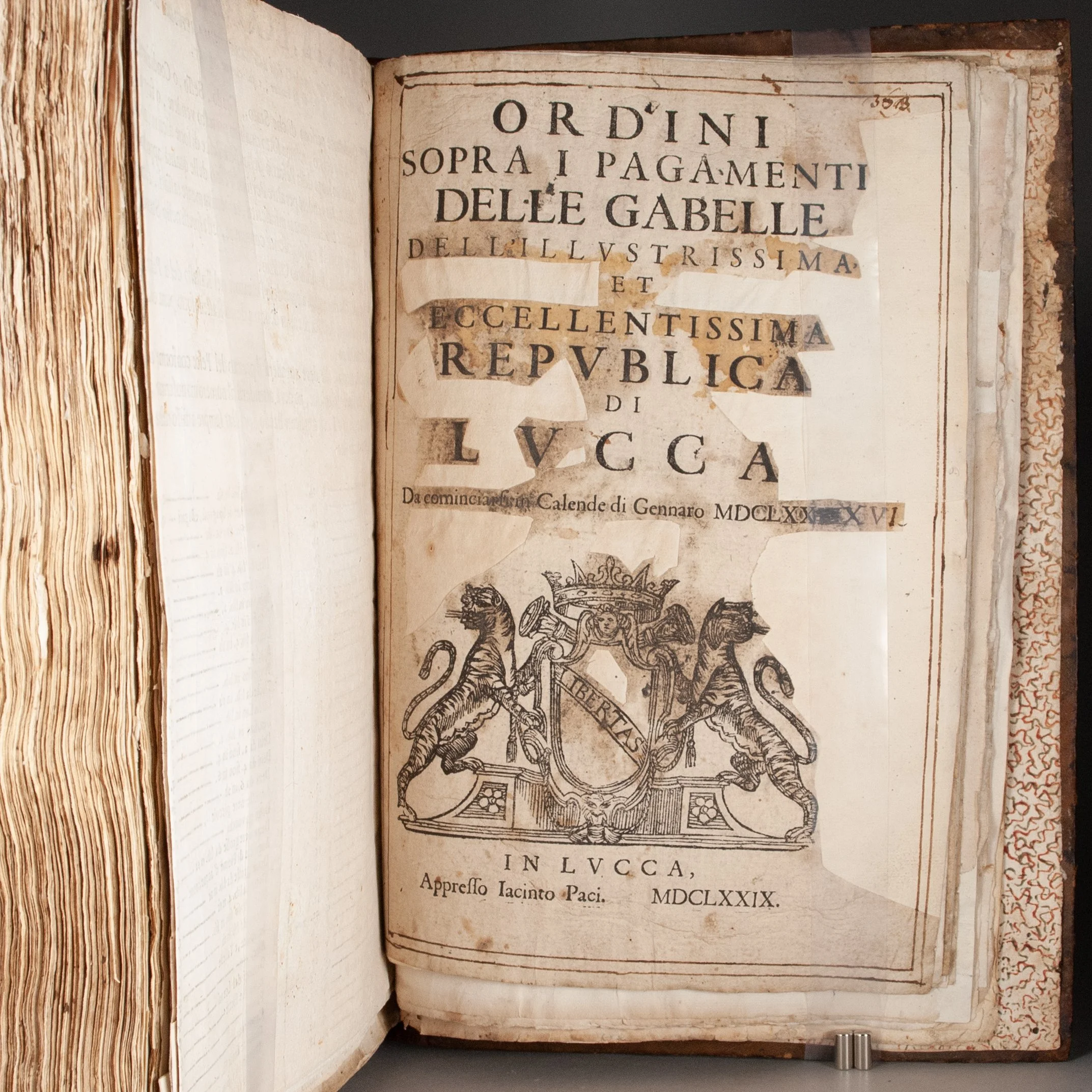

Lucensis civitatis statuta nuperrime castigata et quam accuratissime impressa [bound with] Ordini sopra i pagamenti delle gabelle dell'illustrissima et eccellentissima republica di Lucca da cominciarsi in calende di gennaro MDCLXXIX [and thirteen related ephemeral pieces, plus some manuscript content]

Lucca: Giovanni Battista Faelli (Joannes Baptista Phaellus), 1 March 1539

[6], cccxxx, cccxxx-cccxxxix leaves | Folio | pi1(=3L6) A^6(-A6 blank) B-2Z^6 3A^8 3B-3F^6 3G^8 3H-3I^6 3K^8(-3K8) 3L^6(-3L6)

Likely the second collection of Lucca's statutes. We find just one earlier collection, issued in 1490 by Henricus de Colonia, who in fact issued editions in both Latin and Italian editions (though the latter may have been more limited in scope). Our printer seems to have continued that tradition, namely with his 1539 Statuti della città di Lucca (USTC 838728). Faelli was a Bologna printer who apparently spent less than a year in Lucca, where we find just five imprints to his name. But he brought his good taste along with him, this edition printed in a handsome roman type, its title within a large single-piece woodcut border—which Faelli was using by 1533—and with a full-page woodcut of Lucca's coat of arms. ¶ An exceptional copy for having bound in at end more than a dozen additional pieces on Luccan law, a trove of ephemera spanning a century and a half, likely brought together here near the end of the 18th century. We find no other copies of any of these additional printed pieces.

(1) A thorough 24-page manuscript index to the printed statutes.

(2) A brief transcription of a decree dated 4 July 1621.

(3) Per parte et comandamento....una relatione fatta da sei cittadini, lis 26. di maggio passato, sopra il pagamento del datio & datia, la qual relatione era dell'appresso tenore. A Luccan broadside decree of 27 May 1621, on the payment of debts, dated 15 June 1621 at bottom and signed by one Pellegrino Giampaoli.

(4) Per parte e comandamento...li 29 aprile prossimo passato. Lucca: Iacinto Paci and Domenico Ciuffetti, 1695. Another Luccan broadside decree, with a focus on the sale of bread, though not without mentioning wine.

(5) Per parte e comandamento...26 febbraro 1584. Lucca: Domenico Ciuffetti, 1701. Another Luccan broadside decree, prohibiting work on important feast days (feste notate), mentioning by way of example weavers, tailors, barbers, coppersmiths, "nor other craftsmen, nor to keep shops open." A list of these official feast days appears at bottom.

(6) Per parte e comandamento... [Lucca]: Domenico Mariani, 1715. Another Luccan broadside decree, regulating the sale of seafood, listing some seventy items and their approved prices.

(7) Ordini sopra i pagamenti delle gabelle dell'illustrissima et eccellentissima republica di Lucca, da cominciarsi in calende di gennaro MDCLXXIX. Lucca: Iacinto Paci, 1679. 6, 9-40 p. A^20(-A4). The 1679 edition of a regular series stipulating the tax owed to Lucca on countless goods, here listed alphabetically. The printed dates have been variously altered by hand to 1685 and 1686, some prices have been updated by hand, and the official's name at end has likewise been changed by hand. Our annotator has added a kind of cheese and salumi, for example, and updated the price of whale bone, as well as some fish prices. Many (most?) editions seem to have disappeared without a trace.

(8) Legge delli 27 novembre 1681 sopra la prohibitione di farsi e vendersi pane fuori di quello delle publiche canove...per tutto l'anno 1694. Lucca: Iacinto Paci and Domenico Ciuffetti, 13 October 1693. A bifolium decree regulating the production and sale of bread.

(9) Nell'eccellentissimo consiglio generale congregato il di 22 luglio 1650 fù letta una relatione fatta da tre dottori alli 30 agosto 1648... [Lucca? 1650?]. A bifolium decree, which appears to bear at least in part on messengers (messi) working for the court, signed at end by Francesco Macarini.

(10) Tariffa sopra la grascia per l'anno 1715. [Lucca]: Domenico Mariani, 23 January 1715. A broadside table listing the taxes on various foodstuffs, hewing closely to the traditional association of grascia with meat, cheese, and oil.

(11) Nell' eccellentissimo consiglio generale, congregato à 13 november 1710 fù letta una relazione...circa la prohibizione da farsi d'imprestiti di denaro, e robbe publiche da quelli, che maneggiano denaro publico, e robbe publiche... Lucca: Domenico Ciuffetti, 22 November 1710. A Luccan bifolium decree prohibiting those who manage public funds from lending money.

(12) Per parte e comandamento...il giorno 15 del corrente mese di giugno & anno 1717... Lucca: Domenico Ciuffetti, 1717. A bifolium decree to ensure that no one is arrested for fines of less than 30 lire. It also touches on food requirements for prisoners, with an additional section of the grascia.

(13) Genesio calco per la Dio grazia, e della S. Sede Apostolica... Lucca: Domenico Ciuffetti, 1718. A broadside decree again stipulating that no person should be imprisoned on account of debt unless that debt exceeds 30 lire, and again briefly touching on the amount of food prisoners should receive.

(14) Per parte e comandamento...29 novembre pross. passato del presente anno 1725... Lucca: Domenico Ciuffetti, 1725. A broadside decree on matters pertaining to debt and debtors.

(15) Per parte e comandamento...de 7 del corrente... Lucca: Vincenzo Ferrerio Bossi, 15 March 1783. A bifolium decree on the administration of cases in the courts.

(16) Three pages of legal text in Latin drawn from a variety of sources.

These additions make for an extraordinary bespoke compendium of local trade law, rich in unrecorded ephemera, with a particular emphasis on the business of food.

PROVENANCE: A heavily annotated copy of the statutes, with marginalia on some 470 pages—nearly 80% of the book—often densely packed, altogether adding thousands of words of manuscript content. The marginalia betray a reader with deep knowledge of local law, frequently adducing precedent from other sources dated throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. You'll find countless notes citing volumes of decisiones, for example. Our annotator demonstrates an equally thorough familiarity with this volume itself, providing numerous cross references to other chapters within the edition. This reader even cross references their own annotations. "See notes below at chapter 42" (fol. 16r: Vide infra notata ad cap. 42), and notes indeed surround Ch. 42 at the foot of fol. 30v. We find a similar note at the foot of fol. 33r (Vide notata ad cap. 128), and no doubt close inspection will reveal still more. As if to render the book as practically useful as possible, our reader has updated the list of feast days on fols. 13-14, changing some dates and adding new ones. Similarly, where feast days are listed without dates on fols. 162v-163r, our reader has added them by hand. “These kinds of annotation take a printed book as a base to create something different and enhanced, where the combined input of author and user produces a unique, personalized manual or compendium of practice" (Pearson). ¶ This reader's system, to use the printed text as a repository for additional relevant knowledge plucked from elsewhere, was not at all unusual, perhaps particularly for lawyers. "Especially in books which were tools of everyday use," Holger Schott wrote of English lawyers, citing their collections of statutes and reports, "the margins are usually riddled with references to more recent statutes, cases reported in print or manuscript or at which the reader himself had been present, other treatises, as well as internal cross-references, queries, notes highlighting contradictions and surprising decisions, expository summaries, and critiques." There's obvious utility in having all relevant information readily accessible in a single place. And for one early reader, this was that book, this became the comprehensive, personalized legal handbook that could not be bought, that could only be built, an archive for everything that might facilitate their work. ¶ Beneath the Luccan coat of arms, here repositioned at the front of the volume, is the signature of one Joannis Michaelis Barsanti. We suspect this is the same owner who added the many additional ephemeral pieces. We do find evidence of a Giovanni Michele Barsanti in Lucca in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

CONDITION: A very wide-margined copy in later marbled leather, probably late 18th-century, neatly rebacked; with some dizzying paste paper paste-downs. Catchword on 3K6v corrected in manuscript, very likely by the printer; the British Library's digitized copy has a cancel slip pasted over the original catchword. The full-page arms of Lucca (3L6), here trimmed and mounted, has been moved from the back of the book to the front. Most of the additional pieces are accompanied by a brief handwritten title on an otherwise blank leaf. A handwritten table of contents precedes the printed 1621 document. ¶ Bifolium G1.6 likely from another copy, trimmed much shorter and with annotations in a different hand; scattered dampstaining, and old moisture damage to the upper fore-edge through most of the volume, with some loss affecting marginalia; some occasional marginal repairs; generally soiled and well thumbed in the lower corners, the paper often thin and weak from so much handling. The added Ordini lacking leaf A4, its title carefully trimmed and mounted, the text generally shabby and soiled; many of the printed ephemera have been folded to fit within the covers, and the bottom inch or two of the 1701 and 1715 broadsides may have been bound shut; grascia table trimmed close at top and bottom; some repaired tears in the ephemeral pieces. Boards scuffed and worn, but repaired at the extremities. A sturdy, well functioning book.

REFERENCES: USTC 838727; EDIT16 CNCE 32542 ¶ Isa Belli Barsali, I palazzi dei mercanti nella libera Lucca del '500 (1980), p. 101 ("a beautiful edition in folio, executed with typical Bolognese type, which the printer certainly brought with him from that Emilian city"); Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin (David Gerard, tr.), The Coming of the Book (1984), p. 282 ("The cultured reader in the 16th century seems to have been more interested in law than in geography or natural science or even perhaps than in medicine...Collections of statutes sold in large numbers...The fact is no surprise to us if we remember that at this time lawyers and jurists formed a large proportion of the book-buying public. More than three-quarters of the French libraries of which we have any knowledge at this time contained a great number of law texts, and many law books belonged to people who might not be expected to have much interest in law."); William H. Sherman, Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England (2008), p. 144 (for the Schott quote; Sherman adds, "Lawyers-in-the-making would also have learned to take notes of various sorts, first and foremost in the form of marginalia"); David Pearson, Speaking Volumes: Books with Histories (2022), p. 60 (cited above); H.J. Jackson, Marginalia (2001), p. 25 (“Not scholars or ex-scholars only, but readers of all sorts similarly collected, in the front of their books, materials from other books that could be used as aids and reinforcements for the reading of the book at hand. Notes of this kind are not original, but they indicate by the principles of selection and by the trouble taken to preserve them the frame of mind that the reader considered appropriate in the approach to the work.”), 110 (“Although we have to exercise caution whenever we generalize on the basis of few (let alone single) or exceptional examples, all the same reading and writing are social arts—socially condition, socially transmitted—and are consequently dependent on sets of shared assumptions and conventions"), 255-256 (responding to Robert Darnton, "we should be able to capture not just ‘something’ but quite a lot ‘of what reading meant for the few persons who left a record of it’—and for others besides…Marginalia for all their faults stay about as close to the running mental discourse that accompanies reading as it is possible to be, and if we want to understand that process we are better off with them than without them”)

Item #859