Woman's peasant binding

Woman's peasant binding

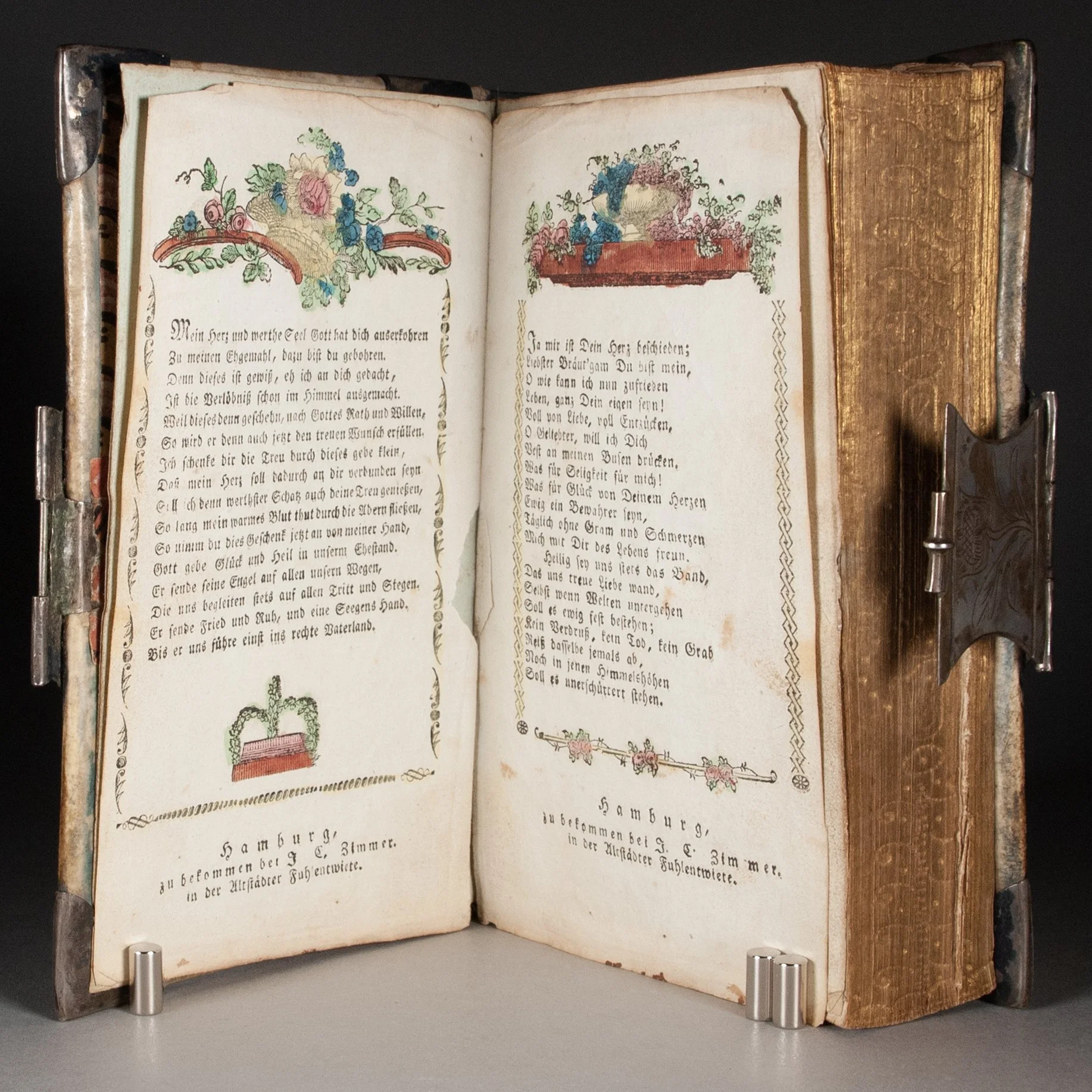

Allgemeines Gesangbuch, auf königlichen allergnädigsten Befehl zum öffentlichen und häuslichen Gebrauche in den Gemeinen der herzogthümer Schleswig und Holstein gewidment und mit könighlichem allerhöchsten Privilegio herausgegeben; neunzehnte Auflage [bound with] Communion-Buch...neue Auflage [and additional printed pieces]

Communion-Buch by Johann Otto Wichmann

Kiel: Königlichen Schulbuchdruckerey, 1813 | Hamburg, [ca. 1800?] | Hamburg: Johann Christoph Zimmer, [ca. 1800]

[4] handbills; [24], 510, [10]; 22, [2]; 128 p. + [3] leaves of plates; [56] p. | 8vo | a^8 b^4 A-2I^8 2K^4; )(^8 2)(^4; A-H^8; 1-3^8 4^4 | 174 x 102 mm

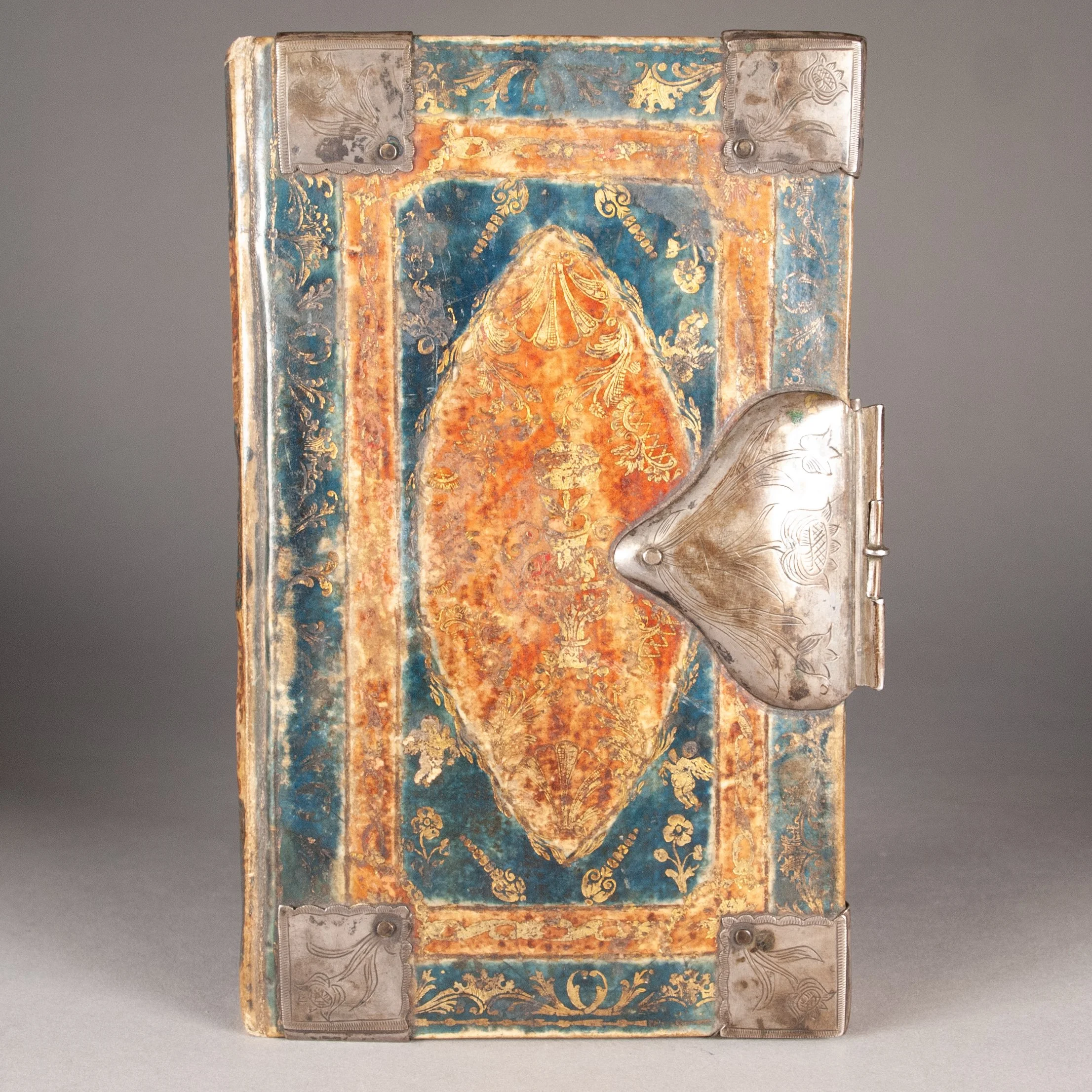

A German hymnal for residents of the Schleswig-Holstein region, today Germany's northernmost state, first published perhaps in 1781 and here in its stated 19th edition. The territory has deep historical ties to Denmark—the book's privilege was issued by Christian VII, King of Norway and Denmark—but the area was increasingly disputed in the 19th century and found itself part of the German Empire in 1871. We've traced no other copies of this "new edition" of Wichmann's Communion-Buch; we find only the first edition, printed at Hamburg in 1785. VD18 reports no illustrations in the first edition, and our three plates are stylistically quite different, so we suspect the illustrations were added by the owner. Combined with the supplementary sections following the hymnal proper—a variety of prayers and a selection of gospel readings for Mass—the whole thing would have a functioned nicely as a Lutheran’s complete vade mecum. We're particularly taken by the four hand-colored songs added at front, each formatted as a standalone handbill (intact as two conjugate bifolia). The printer's VIAF record places him at this address until ca. 1800. ¶ It had long been standard practice to publish hymns and psalms without musical notation, as the tunes were familiar or simple enough to pick up by ear. The publisher has indicated the appropriate tune for many of these, which should have been enough for most—Mel. Ich ruf zu dir, Herr, for example, or Mel. O liebster Jesu, was. Relatively few were able to read music anyway. “Notation, never commanded by congregations,” at least in early America, “was the property of the smaller, more musically committed group which sang in harmony” (Crawford and Krummel). The book offers a robust 914 numbered hymns, with an index of titles at end. Hymn numbers displayed during service would likely have been mapped to those in the present text, a clear benefit of having a standardized book for everyone in a given community. It’s a substantial collection that benefited from generations of tradition and accretion. “Hymn-books offered an enormous range of ‘joyous’ or comforting songs, which even pious servants and labourers would pick up from their mistresses and masters at work. They were sung in fields, during long journeys on foot or in coaches. The repertoire of these hymns changed and expanded with time,” reflected in these thick hymnals of the late 18th century (Rublack). In contrast to Catholic Mass, the congregational hymn became a defining element of the Lutheran service, really an extension of its theology. "The song both symbolized and realized the principle of the direct access of the believer to the Father” (Schoenbohm). ¶ Of course we're big fans of the combination and repackaging of print, but we're mostly here for this enchanting binding: parchment dyed red-orange and turquoise, then tooled all over in gold, with a silver clasp and corner pieces engraved with tulips, and the gilt edges gauffered. While we're not accustomed to finding them quite this far north, the dyed parchment and exuberant tooling should be sufficient to call this a Bauerneinband, or peasant binding, popular in Central Europe at the time. “Spectacular through the richness and polychromy of the décor,”these bindings probably originated in Hungary, “then spread to Germany, the Netherlands and the northern countries, in the 17th-18th centuries” (Carșote). While it’s been suggested that Bauern might refer to peasant owners or production by untrained craftspeople, which is perhaps true in some cases, it more likely refers simply to a folk decorative style. ¶ Our tooling is admittedly more traditional than many other Bauern motifs, but certainly unrestrained and over-the-top. Peasant associations aside, this would have been a relatively extravagant binding, commonly found on the kind of religious texts that would have made suitable gifts. The skills demonstrated certainly exceeded those of the amateur. We should note that Danish binders were of course capable of producing richly imaginative work. (You should see their playful adaptations of the Cambridge panel binding.) Larsen and Kyster do reproduce a parchment binding dyed and tooled in gold, attributed to Copenhagen binder Martin van Fenden, ca. 1725, and in 2019 Quaritch offered an 1804 edition of this Kiel hymnal in a peasant binding.

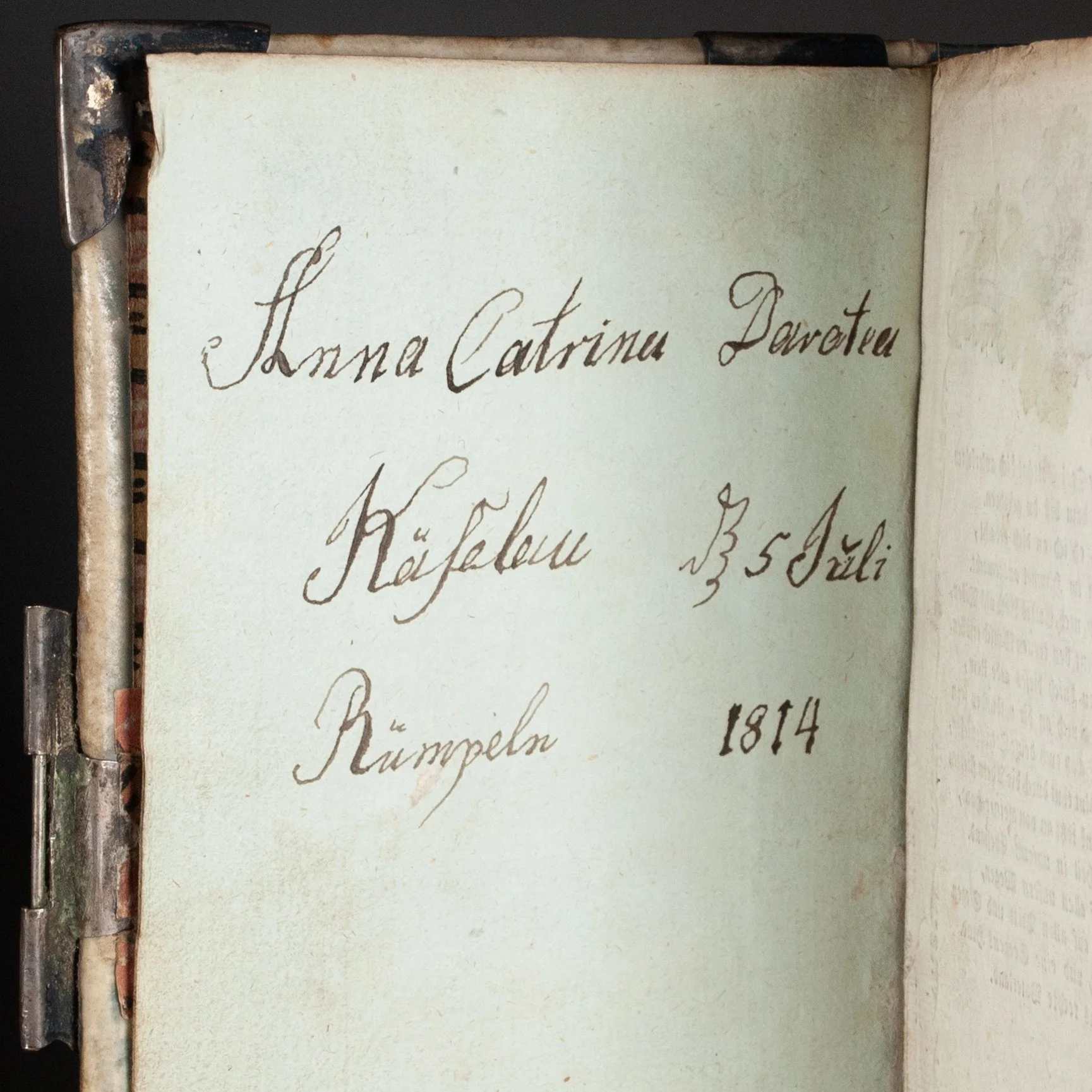

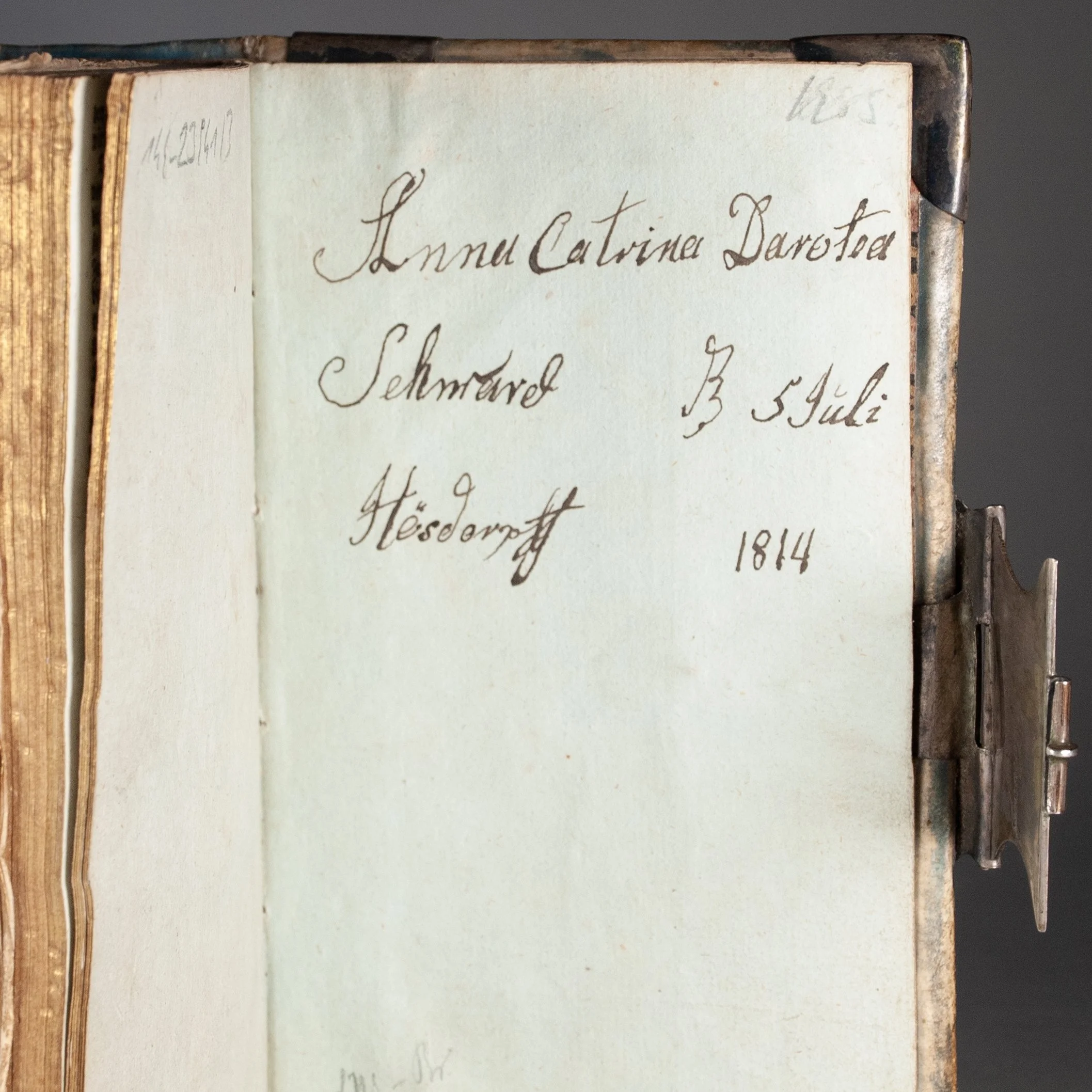

PROVENANCE: Front fly-leaf with the ownership inscription of Anna Catrina Dorotea Kaselew of Rümpel, Germany (a small village northeast of Hamburg), dated 5 July 1814. The same Anna has inscribed her name on a reaf fly-leaf, with the very same date, but instead with surname Schward or Schwarck and place name Hëssdorpff(?). The inside of the silver clasp, meanwhile, is inscribed T.H. Schwarck, 1814. We're not sure what to make of this, except to suggest that the book might have been a wedding gift from T.H. Schwarck to his new wife Anna Catrina (née Kaselew). Anna would have had one surname when she woke up on July 5, and another when she went to bed. Both the content and the binding would have made for an eminently suitable gift.

CONDITION: Contemporary parchment peasant binding, as described above, with block-printed paste paper endpapers. ¶ First handbill bifolium detached and split halfway up the fold, and these four leaves moderately soiled; three leaves in the Communion-Buch loose but still attached (inserted plate surrounded by a bifolium). Binding a little rubbed, and a bit of the color lost; silver tarnished; paper split along the front hinge, but all cords remain intact. Really quite nice, inside and out.

REFERENCES: On the text: Ulinka Rublack, Reformation Europe (2017), p. 232 (cited above); Richard Crawford and D.W. Krummel, “Early American Music Printing and Publishing,” Printing and Society in Early America (American Antiquarian Society, 1983), p. 189 (“The printed tunes [in early America] were almost certainly known to the people who sang them; and if they were not, they were few enough in number and uncomplicated enough in style to be learned simply by ear. It seems more likely that the tunes were included [in later Bay Psalm books]…in order to record, for the few who could read music, an official version of each tune.”), 190 (cited above); Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen, The Bookshop of the World: Making and Trading Books in the Dutch Golden Age (Yale, 2019), p. 131 (on psalters: “The absence of musical notation became, indeed, the norm rather than the exception”), 234 (“Singing, at home, at work, in the tavern and on the streets, was a ubiquitous part of life in seventeenth-century Europe. For the print industry it became big business. Collections of songs were as old as print itself, drawing on songs sung in the tavern or workplace, or by mothers at the crib.”); Richard Schoenbohm, “Music in the Lutheran Church before and at the Time of J.S. Bach,” Church History 12.3 (Sept 1943), p. 195 (“The musical system of the Catholic church proceeded from the Gregorian chant which is strictly a detail of the sacerdotal office. The Lutheran music, on the contrary, is based primarily on the congregational hymn.”), 196 (cited above), 197 (cited above; “the secular folksong of the 16th century was a very prolific source of the German chorale”), 204 (in an early Lutheran service at Leipzig, for example, perhaps around the time of Bach, the hymn number “was not announced, but from tablets placed in conspicuous places around the building, the numbers of all that were to be sung during the service could be read”); VIAF 1037649591 ¶ On the binding: Cristina Carșote, Luminița Kövari, Carmen Albu, Emanuel Hadîmbu, Elena Badea, Lucreția Miu, and Gabriela Dumitrescu, “Bindings of Rare Books from the Collections of the Romanian Academy Library: A Multidisciplinary Study,” Revista de Pielarie Incaltaminte 18.4 (2018), p. 311 (cited above); Julia Miller, Books Will Speak Plain (Legacy Press, 2010), p. 223 (“The association with peasants appears to reflect the use of folk decorative motifs on the bindings rather than peasant production”); Mirjam M. Romme, “Contemporary Collectors XLIV: The Henry Davis Collection I: The British Museum Gift,” The Book Collector 18.1 (Spring 1969), p. 36 (“Later in the 18th century we get the so-called Peasant bindings, usually found on books printed in Germany, Holland, Switzerland, and Eastern Europe”); Sofus Larsen and Anker Kyster, Danish Eighteenth Century Bindings 1730-1780 (1930), plate LIX; Bernard Quaritch, New Acquisitions April mmxix, #12

Item #771