Holy relic and pilgrim souvenir

Holy relic and pilgrim souvenir

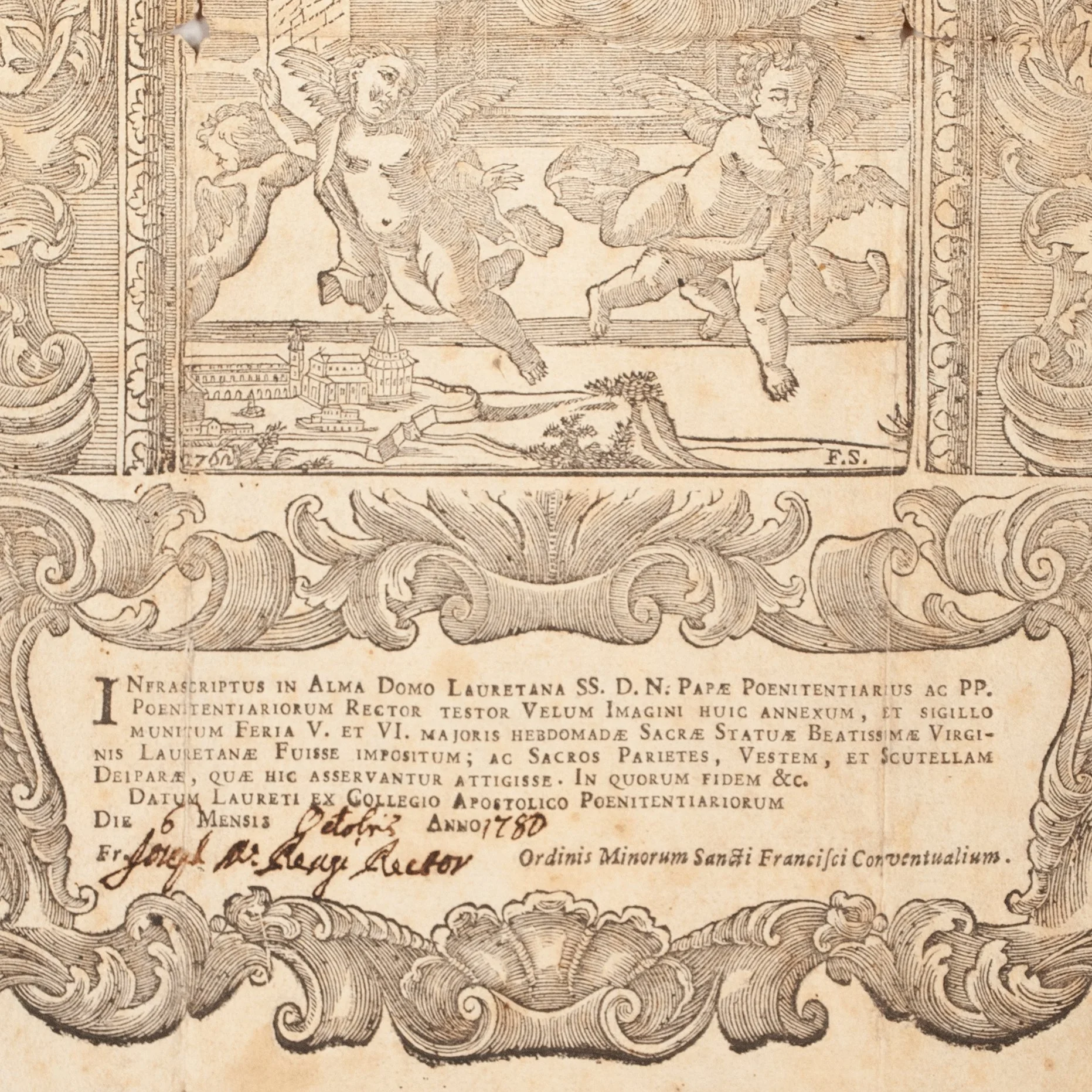

[Marian relic from the House of Loreto]

Loreto, 1780

1 broadside | Full-sheet | 430 x 295 mm

A potent contact relic from the miracle-working House of Loreto, certifying that the piece of black veil here attached covered that church's famed Madonna statue on Maundy Thursday and Good Friday, 1780. The late medieval statue of the Virgin and Child had long adorned the altar in the Basilica della Santa Casa (and was replaced following a fire in 1921). This fragment of black textile, which represents a kind of mourning veil, should have helped its owner more deeply experience the grief Mary felt during her son's suffering and death. The certificate is signed by a priest, dated 6 October 1780, and further asserts that the cloth touched the church walls, vestments, and Mary's scapular (ac sacros parietes, vestem, et scutellam Deiparae). ¶ Among the vast genre of holy relics, contact relics are those that had been in physical contact with saints or their primary relics. Rather exceptionally in this case, the entire House of Loreto is considered a relic, for it's venerated as a site where the Virgin and Child once lived, the house having been transported by angels from Nazareth (hence the airborne abode in our woodcut). Loreto was (and perhaps remains) one of the most popular pilgrimage sites in the Christian world, and contact relics like this would have been popular pilgrim souvenirs. After Easter, those who made the journey for Holy Week might acquire a piece of the veil used during that year's services. ¶ A visit to a place like Loreto might have been the journey of a lifetime, as such pilgrimages were “often the highlight of the lives of the travelers,” and so “they were prepared to proceed at a leisurely pace, indulging in stopovers and detours, and to spend a meaningful amount of time at their destinations” (Hunt). While a souvenir could recall pleasant memories of the experience, they could play a serious, enduring role in one’s devotional life. “Indeed, in their function as contact relics,” here considering 15th-century images, “these tokens allowed a more direct experience of the cult image than was available at the shrine itself” (Areford). ¶ More than an object of devotion, documents like this could play a medical role, too, when the relic in question reportedly possessed curative properties (as the Madonna statue at Loreto did). They functionally served as a pillar of early modern medicine, along with folk remedies and other appeals to the supernatural. "They were, moreover, not ‘second-best’ cures, sought out only in desperation or by the ignorant and impoverished. They were the everyday face of medicine and medical practice" (Lindemann).

CONDITION: Printed on the recto only of a single sheet of laid paper, the woodcut signed F.S. and dated 1762. A small piece of cloth remains attached beneath the embossed paper seal of the House of Loreto; a larger piece, detached due to the textile's fragility, is loosely laid in. ¶ Creased across the short dimension and twice along the vertical dimension, with occasional loss and some large closed tears; foxed and a little soiled; remnant of paper along the top edge of the verso, probably from an old mounting.

REFERENCES: Karen Vélez, The Miraculous Flying House of Loreto (2018), p. 15 ("The Santa Casa was also an extraordinarily spectacular reliquary," sometimes compared to the Ark of the Convenant and Holy Sepulcher. "Unlike churches, which are often described as figurative 'houses' of God and which also contain relics, the Santa Casa was purportedly the real deal, the actual house of Christ and Mary."); Edwin S. Hunt and James M. Murray, A History of Business in Medieval Europe, 1200-1550 (Cambridge Univ, 1999), p. 68 (cited above); David S. Areford, “Multiplying the Sacred: The Fifteenth-Century Woodcut as Reproduction, Surrogate, Simulation,” Studies in the History of Art 75 (2009), p. 127; Margaret Meserve, Papal Bull: Print, Politics and Propaganda in Renaissance Rome (2021), p. 258 (attesting to Loreto's healing properties); Mary Lindemann, Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe (2010), p. 2 (cited above), 15 ("Few relied on either secular or spiritual healing exclusively; most people used several cures or forms of medicine concurrently or sequentially")

Item #758